Peter and Algernon Hulse

Introduction

I recently wrote about the scholarly career of my great-great-grandfather Algernon Jeremiah Hulse on the Antigone website. In his later years (during the early 19th century), he was the priest of a parish on the outskirts of Staffordshire who, when not preaching sermons to a sparse congregation, published variously on Classical matters. His only companions were a housekeeper of advanced years, Mrs Eurycleia Smith, a learned cat called Cicero who loved to recline on his Classical dictionaries and lexica, a voluble parrot called Cassandra, and his ever-faithful hound Argos, of somewhat decrepit appearance.

I since discovered more of his exploits when I returned to researching the family archives, in a dusty handwritten manuscript with the same title as this present piece. As a younger man – the work was dated 1789 – it appears that my great-great-grandfather was an intrepid explorer of the Middle East, travelling first to Constantinople and then being one of the first gentleman scholars to visit the Classical sites of Southern Anatolia.

Arrival in Constantinople

He describes his arrival in the chief city of the Sublime Porte in typically florid style:

With my eyes rivetted on the opening splendours, I watch’d, as they arose from out the bosom of the circumjacent waters, the tapering minarets, the swelling cupolas, and the innumerable abodes, which, whether stretching far along the sinuous shore, mirrored their semblance in the wave, or clambering the precipitous sides of the mountains, trac’d their airy outlines upon the azure firmament above.

Reception in Constantinople

Algernon must have been remarkably well-connected at this stage in his life, recluse though he later became, as his reception seems to have been on a lavish scale. The dinners he attended featured both Ottoman luxury and concessions to European tastes, as he notes:

The dinner was equally splendid & better Cooked & served earlier than usual, one dish of these dinners seems invariably to be, their favourite one of a Lamb baked whole & stuffed with rice … We had in the Hall, during dinner, besides the Chapter of Priests & attendants innumerable, a Band of Greek music which at first I thought very harsh, but whether they improved, or our ears became accustomed to it, I cannot say but it was at last very tolerable.

Down to Rhodes

After his stay on the Bosphorus, Algernon seems to have continued his journey by easy stages down through the islands of the Aegean, until finally arriving on the island of Rhodes, he made the easy crossing back into Asia Minor. He writes:

For those who draw nigh unto the coast of Pamphylia from Rhodes on a clear day, aboard one of the diminutive and less-than-inviting steamers of English or Hellenic make – the sole conveyances afforded to travellers in these waters – there unfoldeth an unbroken succession of scenes, at once majestic and entrancing.

It is distinctly possible that my great-great-grandfather’s story owes something to the imagination… There may well indeed be doubts about the reliability of the written sources and their transmission!

His recollections, however, are typical of travellers of that period who intrepidly explored the Anatolian plateau and then afterwards wrote and published their stories. When the opportunity presented itself, My wife, Rosemary and I, could not resist the opportunity to follow in their footsteps.

Late last year, therefore, we whirled through Southern Anatolia and parts of Asia Minor at a pace that would have astonished Algernon and even the Great Alexander. The map above gives a rough idea of the ground that we covered on our Magical Mystery Tour (some 2,800 kilometres) and the things and places that we visited and saw. We were led by a latter-day dragoman of very high quality named Mustafa Çalışkan, assisted by a driver named Urük, possessed of an iron constitution.

To the Ancient Greek City of Perge

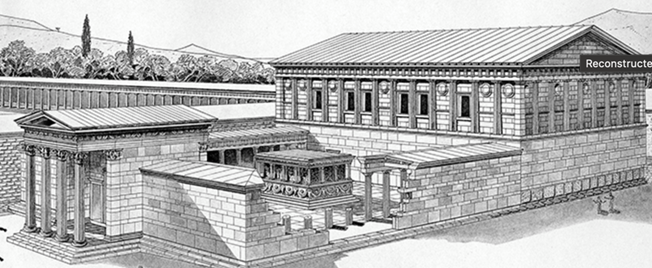

Following the footsteps of Alexander the Great, we came first to Perge. Alexander’s envoys must have also been impressed when his army reached there in 333 BC and the citizens opened the gates to them. It is difficult to visualise what the city looked like then; the view below shows both Greek and later Roman remains. However it must have been fine and spacious, surrounded by fertile and green countryside, with the River Cestrus flowing near by, bringing trade to the city.

Algernon was particularly struck by the city’s sophisticated water management system:

Most ingenious is the central water channel that runs the length of the main colonnaded street. The water flows in a series of cascades, creating both a pleasing sound and a cooling effect in the Mediterranean heat. The engineering skill required to maintain consistent water flow while preventing flooding is remarkable. At intervals, one observes clever mechanisms for controlling the water level – truly, the ancients were our masters in hydraulic science.

Strabo (14.4.2) notes that Perge was one of the principal cities of Pamphylia, and archaeological evidence confirms his assessment. The city’s layout reveals sophisticated urban planning. The colonnaded street, approximately 20 metres wide, runs north-south for about 300 metres, its marble paving still largely intact. The columns that once lined it bore distinctive red Docimian marble capitals, some of which can still be seen lying where they fell.

It had other famous visitors in Antiquity apart from Alexander. Verres, the arch-villain of Cicero’s speeches against him, heard that Artemis’ temple at Perge was rich and sent his thugs to plunder it. There are pleasanter reasons to remember Perge. Apollonius of Perge (c.262–c.190 BC), to be ranked alongside Euclid and Archimedes as one of the greatest mathematicians of the ancient world, perhaps scratched his diagrams in the dust of the city’s agora and it should not be forgotten that another famous figure called in to the city on his travels. St Paul, together with Barnabas, visited the city on their way to Antioch. He had undoubtedly heard of the cult of Artemis Pergaia. Possibly he viewed his visit as a rehearsal for the later riot of silver smiths that he provoked at Ephesus: “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” He did not stay long at Perge!

Aspendos: Monument to Roman Engineering

Algernon’s approach to Aspendos begins with the remarkable aqueduct:

Upon first glimpsing the aqueduct of Aspendos, I was put in mind of the great works of Rome herself. Here in distant Pamphylia, Roman engineering reaches its apogee. Most remarkable is the siphon system, whereby water, conducted through lead pipes of substantial diameter, descends into the valley only to rise again with undiminished force. The precision required in the casting of these pipes, I am informed, was of the highest order, each section being fitted to the next with extraordinary care.

The aqueduct system he describes remains one of the most sophisticated hydraulic engineering achievements of the ancient world. The inverted siphons, which utilised pipes made of stone and lead, overcame a height differential of over 40 metres. The pressure at the lowest point of the siphon would have reached approximately four atmospheres, requiring exceptional manufacturing precision in the Roman period.

But it is the theatre that draws most visitors’ attention today, as it did in Algernon’s time:

The theatre presents itself in a state of preservation that beggars belief. The stage building rises to its full ancient height, adorned with columns and statuary niches that speak to the highest achievements of Roman architecture. Most remarkable is the acoustic property of the auditorium – a whisper from the stage may be heard distinctly in the uppermost rows, while a coin dropped upon the central stone rings clear as a bell throughout the theatre.

The theatre, built during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (AD 161–80), is indeed a masterpiece of Roman architecture. Its cavea (seating area) has a diameter of 95.5 metres and could accommodate approximately 12,000 spectators. The stage building (scaenae frons) rises to an impressive height of 20 metres and demonstrates sophisticated engineering in its construction. The roof over the stage, supported by wooden trusses, was designed to enhance acoustics while protecting performers from the elements.

Konya: City of Whirling Devotion

The approach to Konya sparked particular interest in my ancestor:

As we drew nigh unto Konya – the ancient Iconium – I observed how the minarets pierced the sky like so many needles, while the great dome of the Mevlana’s shrine dominated all. Most curious was the sight of dervishes, who, I am informed, seek communion with the divine through the act of whirling. Their white robes, when they perform their sacred dance, billow like sails caught in a gentle breeze.

The Mevlâna Museum, formerly the lodge of the Whirling Dervishes, represents the architectural traditions of medieval Seljuk Turkey. The complex developed around the tomb of Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–73), known to his followers as Mevlâna. The distinctive green dome, rising 25 metres above the mausoleum, was added in the 16th century. Below it lies the tomb of Rumi, covered with a remarkable sarcophagus decorated with verses from his works inlaid in gold.

The ‘semahane’ (whirling hall) demonstrates sophisticated acoustic engineering. Its wooden floor, supported by egg-shaped jars buried beneath, creates resonance during the ‘sema’ ceremony. The hall’s dimensions (and particularly its height) were calculated to allow the dervishes’ white tennure robes to billow properly during their rotations.

Cappadocia: A Landscape of Faith

It is not a long way by bus from Konya to the heart of Cappadocia. There are now very good roads all across the plains of Anatolia. When you get there, however, something very strange happens to the landscape, as Algernon discovered on his journey. Cappadocia’s unique landscape drew forth some of his most vivid descriptions:

Never have I witnessed such a curious conjunction of nature’s whimsy and human industry. The very rock has been shaped by the elements into forms that defy description – cones, pinnacles, and towers that seem to belong more properly to a fever dream than to waking reality. Yet within these fantastic forms, generations of monks and common folk have carved out dwellings, churches, and entire monasteries.

My ancestor had a good deal to say about his travels in Cappadocia and, in particular, his visit to the strange village of Göreme, which is now an open air museum and UNESCO World Heritage Site. He seems to have spent some considerable time there. His narrative continues:

The most difficult questions connected with those places are to ascertain the uses for which they were intended, and the people by whom they were made. Some appeared to have been intended for tombs, while others must have been dwelling-places; others, again, from the paintings with which they are adorned, have evidently served as chapels. In the present day many are used as dovecotes, and we saw pigeons flying out of the upper openings, to which there appeared to be no external means of approach; though even these were decorated with red paint, and many Greek letters were inscribed on the outer surface of the rock, round the openings.

The underground cities in the area particularly impressed my travelling ancestor:

At Kaymakli, I descended through eight levels of human industry, each more remarkable than the last. The ingenuity displayed in the ventilation systems, the positioning of wells, and the defensive arrangements speaks of considerable sophistication. Most curious are the rolling stone doors, massive discs of rock that could be moved to block passages in times of danger, yet so perfectly balanced that a child might roll them aside in times of peace.

Recent archaeological studies have revealed that these underground complexes, which could shelter thousands of people, incorporated sophisticated systems for water management, air circulation, and waste disposal. The ventilation shafts, some extending over 70 metres deep, maintained air quality even when the cities were sealed against invaders. They still impress today:

Hierapolis: City of Sacred Springs

His journey continuing, Algernon’s approach to Hierapolis clearly left a profound impression:

As we ascended the gleaming white hill, I could scarce credit that such formations were the work of nature rather than art. The terraces, cascading down the hillside like frozen waterfalls, present a spectacle both beautiful and strange. The ancients believed these waters possessed healing properties, and indeed, the warmth that rises from them, together with their curious mineral content, lends credence to such beliefs.

The site remains as striking today as it was in Algernon’s time. The ancient city of Hierapolis was built at the top of these travertine terraces, taking advantage of the hot springs that have drawn visitors for millennia. The Romans developed it into a spa town, and the remains of the massive bath complex still stand, now housing an excellent museum.

But it is again the theatre that particularly caught my Algernon’s attention:

The theatre of Hierapolis stands among the most perfect I have yet encountered in Asia Minor. Most remarkable is the stage building, which rises to its full ancient height, adorned with a profusion of columns, niches, and relief carvings of exceeding delicacy. The figures of Apollo and Artemis, though somewhat weathered, retain their divine dignity, whilst the Emperor Marcus Aurelius may still be discerned amongst the company of gods depicted upon the frieze.

Today, the theatre is still impressive with its exceptional state of preservation. Built in the 2nd century AD during the reign of Hadrian, and completed under Septimius Severus, its cavea could accommodate approximately 12,000 spectators. Also like we saw at Aspendos, the stage building (scaenae frons) rises an impressive 20 metres, decorated with elaborate architectural elements in the Severan style.

The reliefs depict scenes from the life of Dionysus, appropriate for a theatre, but also include images of Apollo and Artemis, the principal deities of the city.

Recent excavations have uncovered inscriptions that document the theatre’s construction and renovation history, whilst careful analysis of the architectural elements has revealed traces of the original polychromy – the blues, reds, and golds that once made the reliefs even more spectacular.

The remarkable acoustics that Algernon noted still function perfectly:

A whisper from the stage carries clear as a bell to the uppermost rows, whilst the slightest sound made at the centre is magnified tenfold. Truly, the ancient architects understood properties of sound that we moderns have yet to fully comprehend.

The theatre’s position, built against the slope of the hill, does indeed provide both excellent acoustics and spectacular views across the Lycus Valley. The seating, divided into three horizontal sections by two diazomata, demonstrates the sophisticated social hierarchies of Roman society – the lower seats reserved for the elite, the upper for common citizens.

Beyond the theatre lies the city’s remarkable necropolis – one of the largest and best-preserved ancient cemeteries in Anatolia. Algernon writes:

I have never witnessed such a profusion of sarcophagi and tomb monuments, stretching as far as the eye can discern. The departed citizens of Hierapolis seem to have vied with one another in the grandeur of their final resting places, each tomb more elaborate than the last. Most curious is the prevalence of holes bored into these stone coffins – the work, I am told, of grave robbers seeking treasure in ages past.

Ephesus: The Jewel of Asia Minor

Algernon’s account of his arrival at Ephesus captures the majesty that still awes visitors today:

As we approached from the heights above, the great city of the Ephesians spread before us like a marble dream. Though much lies in ruins, the grandeur that caused Strabo to name it “the greatest emporium of Asia Minor beyond the Taurus” cannot be mistaken. The great theatre, rising tier upon tier up the hillside, seems poised to echo once more with the cries of “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

Most remarkable is the Street of the Curetes, which my local guide informs me was named for the priests of the great goddess. The marble paving stones still bear the marks of ancient chariot wheels, and one can discern the sophisticated system of water channels beneath. The street is adorned with numerous monuments that speak to the city’s wealth – here a temple to Hadrian, there the public latrines where, I am told, the citizens would gather to conduct both their business and their business affairs!

Algernon was so struck with wonder at what he saw at the site, that he later composed some verses both in Latin and English:

Celsi doctrina tumulus qua surgit in altum,

Ingenii surgit gloria rara viri;

Marmorei fulgent apices et sculpta columnis

Ornamenta, aevi quae sine fine manent;

Hic et Curetum calles, ubi mystica reges

Numina laudabant, sanctaque verba dabant;

Quaeque columna sacros ritus legesque vetustas

Narrat, et antiquos commemoratque pios;

Quis theatri molem verbis cantare valebit,

Milia quo populi carmine capta sedent?

Nunc etiam resonant tragico suspiria fato,

Quae Graium toties exacuere genus;

Sed super omne decus stat gloria maxima divae

Artemidos, flammis occidit icta feris;

Septem inter mundi miracula templa nitebant,

Inter quae surgens illa beata micat;

Nunc ubi fatidicae sonuerunt omina vocis,

Vastatis crescunt gramina sola locis;

Tempus edax quamvis Ephesi monumenta fatigat,

Stella velut, lucet gloria prisca tui.

Where Celsus’ tomb in learned splendour stands,

A beacon raised by wisdom’s careful hands,

Lo! Marble columns, crowned with sculpted grace,

Defy the ruin time would dare efface.

Behold the Curetes’ path, where once were trod

The feet of kings and priests who spoke for God;

Each pillar tells, in silent stone decreed,

The rites, the laws, the myths, the mighty deed.

What voice may sing the theatre’s vast design,

Where thousands thrilled to art’s transcendent line?

There, echoing still, in tragic accents roll

The sighs of fate that shook the Grecian soul.

Yet chief of all, great Artemis we name,

Whose temple rose in fire and fell in flame;

Seven times the world its marvels did compose,

And she among them, in her glory, rose.

Now silence reigns where oracles once spoke,

And weeds o’ertake the fanes by empire broke;

Yet Ephesus, though time thy form may mar,

Thy light still shines, immortal as a star.

The Library of Celsus, partially reconstructed in modern times, remains one of the most impressive sights. Built between AD 110 and 135, it originally housed some 12,000 scrolls. The optical refinements include slightly curved stylobates and inward-leaning columns that create an illusion of greater size and perfect proportions. There were also sophisticated engineering solutions to protect the precious scrolls – a double wall with an air cavity helped maintain stable temperature and humidity. Algernon apparently stayed some days in a nearby village – his command of Turkish being much improved by this stage – and then departed for the final two ancient sites of his Anatolian exploration.

Miletus: The City of Philosophers

The city that gave birth to the Greek philosophical tradition deserves particular attention. As Strabo (14.1.6) tells us:

Miletus, the first city of Ionia, situated on the sea, has four harbours, one of which is large enough for a fleet. Many great achievements are attributed to this city, but the greatest is the number of colonies it founded.

Algernon’s observations capture both the physical and intellectual legacy of the site:

To tread the same ground as Thales, who here first sought to explain the cosmos without recourse to myth, fills one with profound reverence. The great theatre, though much damaged, still commands the site. Most remarkable is the layout of the streets – arranged in a perfect grid pattern that, I am informed, dates back to the designs of Hippodamus, who was born in this very city. The precision of the angles and the regularity of the blocks speak to a mathematical mind at work in the very fabric of the city.

The theatre, which could seat 15,000 spectators, remains the most impressive structure at Miletus. Its façade, reaching 140 metres in width, features elaborate decorative elements including masks, garlands, and mythological scenes.

The Bouleuterion, or council house, demonstrates sophisticated acoustic engineering. Its semicircular design, with precisely calculated dimensions (34.8 x 55.9 metres), created perfect conditions for public speaking. The original wooden roof was supported by a complex system of trusses, evidence of which can still be seen in the surviving stone walls.

Didyma: Oracle of Apollo

The final stop made by the weary traveller from Staffordshire was the remains of city of Didyma where the Temple of Apollo represents one of the most ambitious architectural projects of the ancient world. Strabo (14.1.5) tells us:

At Didyma is the oracle of Apollo Didymeus, situated above the harbour. It was ancient, but the temple at Didyma was built by the Milesians, being the largest of all temples. However, on account of its size, it remained without a roof.

The Sacred Way, connecting Didyma to Miletus, stretched for 16.5 kilometres and was lined with statues and monuments. Algernon notes:

The ancient road, though now much overgrown, still retains traces of its former grandeur. Here and there one observes the bases of statues, and at intervals, the remains of fountains where pilgrims might have refreshed themselves on their journey to consult the oracle.

Algernon’s description of the temple captures both its scale and spiritual significance:

Never have I beheld columns of such magnitude – their fluted surfaces rising heavenward like great tree trunks turned to stone. Each flute is of sufficient width that a man might stand within it, and the capitals are adorned with acanthus leaves larger than any I have encountered in my travels. The oracle here was said to rival that of Delphi in antiquity, and standing amidst these massive remains, one can well believe it. Most curious are the stairways, carved within the very walls, by which the priests might have descended to deliver their pronouncements to the anxious suppliants.

The Temple of Apollo at Didyma, located in western Anatolia, was one of the most renowned oracular sanctuaries of the ancient world. Constructed on the site of an earlier temple, the massive structure that survives today dates primarily from the Hellenistic period, initiated by the Milesians in the 4th century BC. It was never fully completed, yet its grand scale – measuring approximately 120 by 60 metres – reflected the importance of the cult of Apollo. The temple housed a sacred spring and an adyton, an enclosed inner chamber where the oracle delivered prophecies. Unlike most Greek temples, it featured an unusual design with a labyrinthine series of corridors and platforms leading to the inner sanctuary. Despite its unfinished state, the temple’s towering columns and intricate carvings testify to the ambition and craftsmanship of its builders, securing its place as one of the most impressive religious sites of the ancient world.

Conclusion: Reflections on Past and Present

Alegernon concludes his manuscript with a reflection that seems as pertinent today as it was in 1789:

In traversing these lands, rich in monuments of antiquity, one cannot help but reflect on the transient nature of earthly glory. Yet in the very act of decay, these ruins acquire a new sort of immortality – they stand as silent witnesses to the heights of human achievement and the depths of human aspiration. The precision of their architecture, the sophistication of their engineering, and the beauty of their ornament speak to us across the centuries. May future generations preserve them with the care they so richly deserve.

Having followed in Algernon’s footsteps across Anatolia, I can only echo his sentiments. These sites, spanning millennia of human civilisation, continue to inspire and educate visitors from across the globe. While much has changed since his time –– the sites are now carefully managed, tourists arrive by bus rather than on horseback, and archaeologists continue to uncover new treasures – the fundamental appeal of these ancient places remains unchanged.

Modern archaeological techniques have confirmed many of my Algernon’s observations while revealing new details he could not have known. Ground-penetrating radar, digital modelling, and scientific analysis of materials have deepened our understanding of these sites. Yet the essential experience of encountering these monuments – the sense of wonder at human achievement and the connection to past generations – remains remarkably similar to that described by Algernon over two centuries ago. That wonder in the face of our inheritance from the ancient world, both in terms of language and culture, must be defended to the last.

These sacred and civic spaces still speak to us across the centuries, telling stories of faith, ambition, artistry, and the eternal human drive to create something lasting. In that sense, perhaps they have achieved exactly what their builders intended.

Algernon’s journey back to his idiosyncratic little household in Staffordshire was an uneventful one. He arrived back at the beginning of the 19th century to continue his life devoted to his sparse congregation, his pets, his studies and his scholarship. We can only be grateful that he took such care to record the story of his travels for future generations.

Peter Hulse is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Nottingham. He has made a special study of Apollonius of Rhodes but has a wide-ranging interest in all aspects of the Classical world. He has written previously for Antigone about a medieval Latin poem about chess, about the tale of some American Argonauts, about the arrival of the celebrity Caecilius in Blighty, about the Helen Episode of Aeneid 2, about Prudentius’ Psychomachia, and about a Roman Journey in Britain. He used to teach Latin, Greek and IT.

Further Reading:

There is more about 18th and 19th travellers to Istanbul and Turkey in general contained in this online database.