Tista Austin vs Armand D’Angour

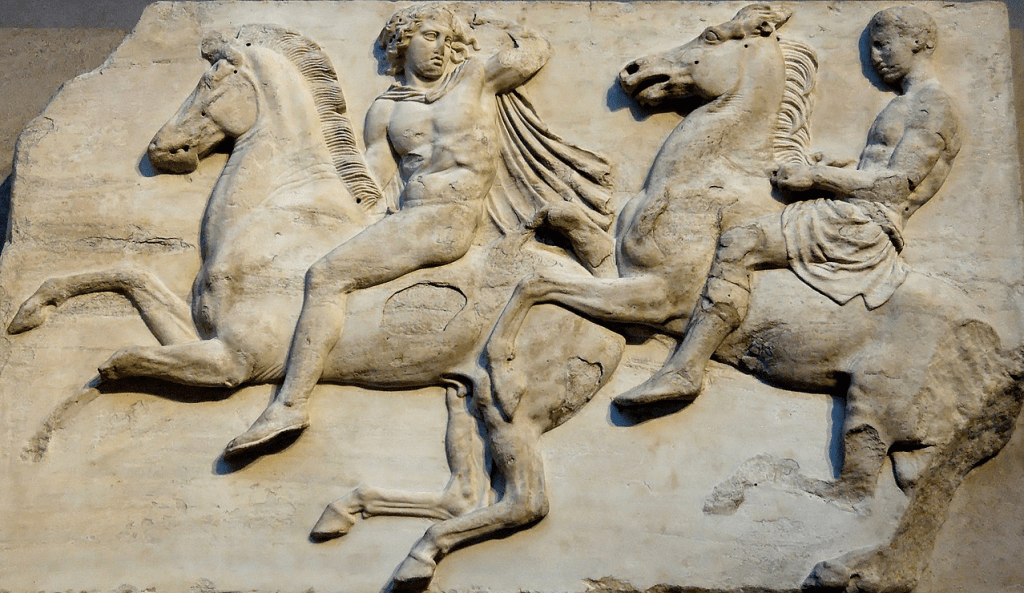

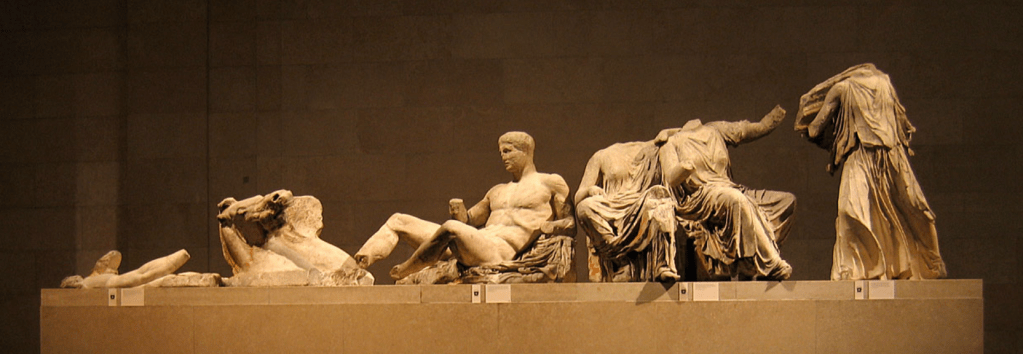

The ‘Elgin Marbles’ form a significant portion of the marbles sculpted for the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis; created by Phidias, Greece’s most famous sculpture, in the 440s and 430s BC, they are among the most famous and inspiring art works in the world. But they are also among the most controversial: the marbles were removed from the Parthenon, then under Ottoman control, by the 7th Earl of Elgin at the start of the 19th century, and calls for their return to Athens (more specifically, to the Acropolis Museum) have in recent weeks reached a new intensity.

The Antigone team felt that it would be healthy to have two writers make opposing cases, one for Britain’s retaining the Elgin Marbles, and the other for returning them to Greece. Each was tasked with making the case in around 1,000 words; they then read each other’s pieces, and offered a 250-word response to their opponent. We publish these four parts below, and end by asking your opinion by poll.

Not only do we think that this debate is a very interesting (as well as emotive) one, touching as it does on issues and tensions that range far beyond this specific case, but we are always determined here at Antigone to model and host what courteous and eloquent intellectual debate looks like. It need not be a dying art.

For Retain:

Who has not gazed across the rock of the Acropolis in Athens – in the ῥοδοδάκτυλος Ἠώς (rosy-fingered Dawn) – without being swayed by the impassioned call to restore the Elgin marbles to their Grecian glory from their entombment in rainy Bloomsbury?

It was Byron who first twisted those heartstrings with his Curse of Minerva, which still falls heavily on his fellow peer and his native shore. Byron’s poetic foresight seems to have prophesied not only the invective of social media but also the fashionable discourse of decolonisation. Restitutionalists miss the irony of mixing Byronic outrage with their righteousness – George Gordon was no conservator: for him the marbles were “Phidian freaks, / Mis-shapen monuments and maimed antiques” which should have been left to Romantic decay. If there is anything to restore, let it be the sage principles of aesthetics, truth and conservation in discussions about the 5th-century BC masterworks in Room 18 of the British Museum.

No other art has had such profound impact as the Elgin marbles. The influence of the broken naturalistic figures on art and architecture was revelatory. For the art historian John Boardman: “In Britain they transformed scholarly attitudes to Greek art world-wide, and have had more effect in the past 200 years than they did in over 2,000 in Athens.” For the first time a great body of Greek sculpture with its achievement of idealised realism was seen in Western Europe, which had hitherto been little acquainted with original work. To the reception of these originals we owe a cultural debt through their influence on the practice of art, on Classical scholarship, as well as the science of archaeology, which have extended far beyond the 19th century to even today.

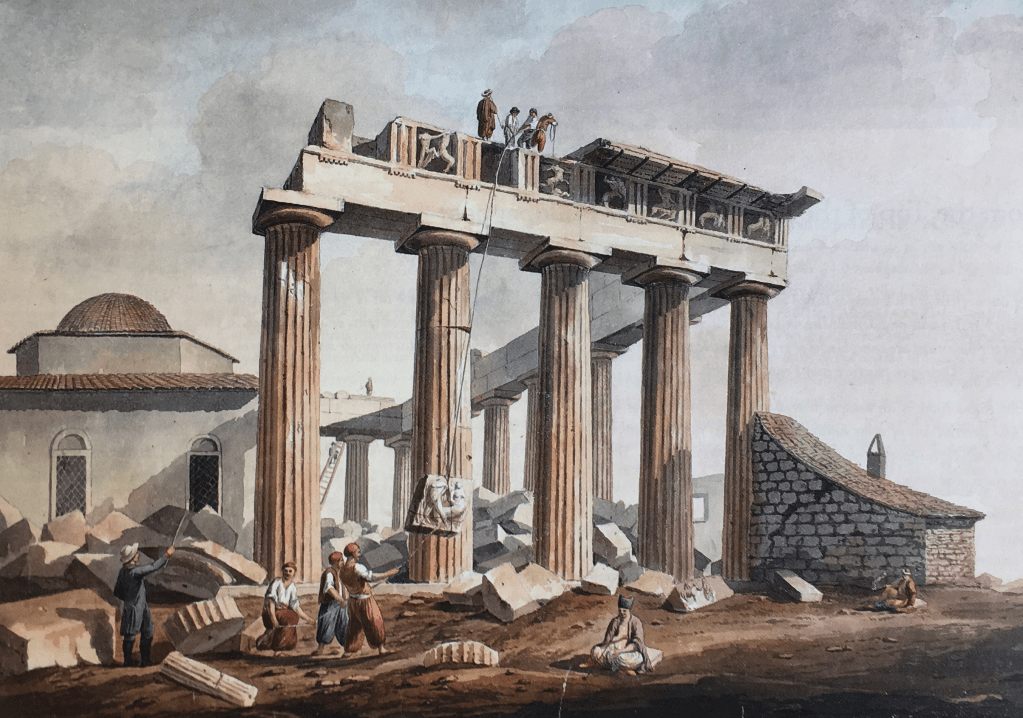

Elgin, whose original intention was to copy and make casts of Greek antiques to promote Classical art, for which he assembled a team of expert draughtsmen, was persuaded to rescue the sculptures from defacement and destruction. The expression ‘Elginism’ was coined by the French to denote the illicit taking of works; one of Elgin’s justifications was to prevent the French, who were aggressively collecting treasures for their Musée Napoléon (otherwise known as the Louvre). The issue from the Ottomans – the recognised governors – of the firmin, the formal instrument which permitted Elgin authority to remove artefacts, is dated shortly after the British victory over Bonaparte in Egypt, while later permission was ratified twice for their shipment.

The legality of the removal of the sculptures from Greece was scrutinised in 1816 by the extraordinary select committee approving the purchase for the nation by Parliament. In 2015, the Greek government was forced to drop their legal challenge to the British Museum’s ownership of the marbles. Instead they changed their strategy to exert maximum political pressure and garner public support, with open claims that they were “stolen” or “looted” – heaping all the vices as can be conjured upon Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin – as much as perfidious Albion – who staked his entire fortune, spent three years imprisoned by the French and died ruined. The evidence of casts made in the 19th century show incontrovertibly that Elgin saved the sculptures from serious damage and deterioration.

The campaign under the tenure of the socialist Culture Minister Melina Mercouri in the 1980s to retrieve the marbles from the British Museum intensified the pathos, fuelling the propaganda, anachronisms and historical revisions now circulating. Mercouri’s talent for emotive hyperbole with her vision of the Parthenon as “the soul of Greece” has turned it into a symbol of nationalistic sentiment, adopted into cultural and foreign policy. Yet the Greek state as we know it today did not exist when Elgin arrived and the Parthenon was a shell of the temple that had stood in Periclean Athens 2,000 years earlier; monuments (such as the Ionic temple on the outskirts of Athens dismantled by the Orthodox authorities) were disappearing, the Turks used the Parthenon as a munitions store while locals ground pentelic marble for lime as a building material or sold carvings to tourists.

The lavish new Acropolis Museum is the legacy of Mercouri’s ‘crusade’. According to its Swiss-French architect Bernard Tschumi, the intention was “to convince the world the Elgin marbles should come back.” It must be the first museum ever to have been constructed in order to attack the collection of another. Dramatically located in view of the Parthenon (where the frieze can never be reinstalled – contrary to the claim that the it can be ‘reunified’ with the temple), the hi-tech presentation displays the marble sculptures Elgin left behind with their distinctive rust-coloured patina against bone-white plaster replicas of those held abroad, to leave no doubt which pieces have been removed. Beauty is not truth here: no trace remains of the Byzantine church or mosque with minaret, and the figures, despite extensive laser work, have deteriorated far more than their counterparts in London. Light pouring through the top-floor glass reproaches the overcast illumination of the frosted skylight of the Duveen Gallery in Britain’s cloudy capital.

When I went there some days ago, the gathering December gloom spread early. The pale frieze marble shone softly under the spotlights as the shadows grew. “You can see the figures better as it gets darker,” the museum guard told me. I asked him if the spotlights were ever switched off. “No, they are always left on, even when the museum is closed.” Though it almost seems like torchlight in a temple, in this gallery where the layout is all wrong (the room is not Greek and the display on an inner wall is ‘inside out’), the light flickers with its strange chiaroscuro over the carvings in the shadow of a ruin lost to time.

Some accuse Lord Elgin of wanting to have the sculptures in his house, but the free access to the British Museum is as close to being in anyone’s home as is possible (compared to the fee-charging Acropolis Museum). “He went again and again to see the Elgin Marbles, and would sit for an hour or more at a time beside them rapt in revery,” wrote Keats’ friend. Room 18 is a space that has inspired art, scholarship, philhellenism. Here is Endymion. And here Mary Datchet not going to the office in Night and Day… As many people (over 6 million) come here as visit Athens in a year.

The restitution of the frieze sculptures to Greece would add nothing to our knowledge of the Classical achievement; it is astounding that more experts do not resist deaccessioning, which is already occurring. The only way to resolve the incessant controversy is not to betray the principles we hold for world conservation by letting artefacts be used as pawns for ‘cultural diplomacy’, national sentiment or politics. Yet rumours of secret talks and deals and long-term-loans echo like Housman’s successive strokes of doom. It is time to recognise that the right home for the Elgin marbles is where they have been since they were saved and brought to world renown here in the British Museum.

Tista Austin

For Return:

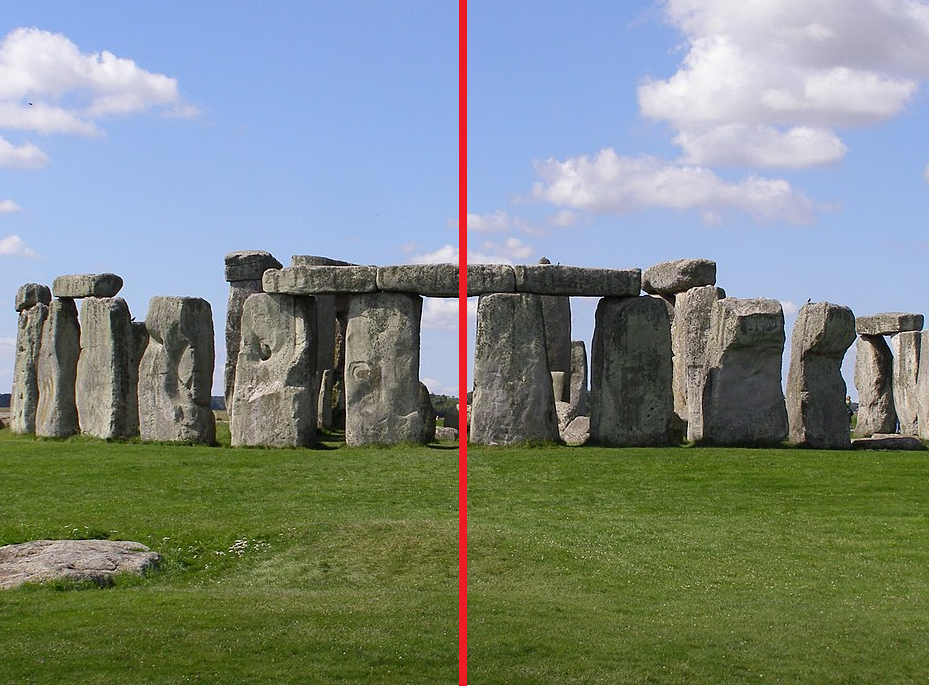

Imagine if, after William the Conqueror became King of England in 1066, he had exercised his royal prerogative to have half of the stone circle of Stonehenge removed to his native Normandy. Centuries later the French-owned stones, supposedly saved from the depredations of English vandals and inclement weather, might have ended up at the Louvre in Paris, offering millions of visitors to that great museum a proud display of that institution’s contribution to the conservation of a site of world heritage.

No-one could suppose, however, that such an act concerning this most iconic of British monuments – albeit one for which little religious or cultural continuity can be claimed – would not nag at the hearts of native Britons (and even non-Britons). Demands for the restitution of William’s semicircle to its native Salisbury would never cease; and the case for restitution would be reinforced by the fact that England and France are close friends on the world stage, with shared cultural aspirations. In this imagined case, the legality of the stone’s original removal would be unimpeachable. However, the sense of aesthetic desecration of the site of Stonehenge, of the need to reunify the stones on their native soil, and of the symbolic importance of returning the “Demi-cercle de Guillaume” to England, would be inescapable.

The removal of the Elgin Marbles from Greece rests on far less solid legal grounds, and the case for their resitution for emotional, symbolic, and aesthetic reasons is no less compelling. This is not a view I have always held. Along with many of my generation in England (I was at school in the 1970s with Noel Malcolm, who has recently published a pamphlet arguing for the retention of the marbles), I was led to believe that the Marbles had been legally acquired, if admittedly only from the Greeks’ then Turkish overlords; that their loss would be a mutilation of the British Museum’s collection; and that after all they had been rescued from potential destruction by Lord Elgin – indeed, that this was his intent. Moreover, it was said that they were far safer displayed in London than in Athens, and that returning them would set a precedent for the wholesale return of treasures from the world’s great museums.

It is now evident that none of these claims is valid. First, the alleged letter of permission (firman) of 1801 may not even have existed. An Italian translation, used in 1816 as proof of Elgin’s legal claim, permits him to take plaster moulds of the statues, and says that he should not be obstructed from taking pieces of stone from the rubble. As William St Clair’s meticulous research revealed,[1] Elgin was an opportunist who removed the stones to adorn his own estate (where important pieces remain), and only sold them to the British Museum, at a loss, when he was on the brink of becoming bankrupt. That it was a noble act designed to preserve the monument for posterity is a convenient myth.

Secondly, few people visit the British Museum simply in order to see the marbles. The wonderful objects that Greece might loan the Museum in return would be a far greater draw, and the Museum owns hundreds of thousands of objects – apart from those recently revealed to have been stolen and sold by a Museum employee – that might be displayed to greater advantage.

No less a myth than that of Elgin’s noble intentions is one that demonstrates the feelings of Greeks. The tale is told that when they were fighting for their independence, some soldiers observed the Turks stripping lead from between the stones of the Parthenon to use for bullets. Unlettered though the soldiers were, they felt this to be a desecration of the monument. They sent a delegation to the Turkish commander with a box of bullets, asking that they be used rather than the building be fatally damaged. Fictional as this tale is, it reflects the emotional resonance of the issue to Greeks. For many, the Parthenon is a vital part of the Greek land and soul, and the despoliation of it by Elgin, compounded by a high-handed or evasive attitude to their return, recently instantiated by the British PM’s unseemly snub to the Greek PM, a fellow conservative, remains an open wound.

Few objects throughout the world have such iconic national significance. Were other museum pieces anywhere considered of similar status, there would surely be an equally strong case for their return to their places of origin. But in fact no museum contains, nor is being petitioned for the return of, a flank of stones from Stonehenge, a section of the Taj Mahal, or the peak of an Egyptian pyramid sawn off its base. The Parthenon sculptures are unique in this respect. Their return to Greece would create no slippery slope for the repatriation of millions of lesser objects that enrich the museums of the world.

Hard-nosed political considerations accord little value to emotional arguments or aesthetic gestures. But in this case the reunification of the Parthenon sculptures – which, it may be reiterated, are only part of the collection of the Elgin marbles – would have a further advantage for its current keepers. The frieze that ran around the inside of the great temple was at a height that made its details less visible than they become at eye level. The figures carved on the metopes would have been obscured in the darkness of the temple’s interior; but in the flickering light of flames viewers would have observed a marvellous moving tableau – a colourful procession of men, women, and animals.

Might not the British Museum honour the story and significance of the Marbles by first returning the original pieces to the Acropolis and then using the tools of modern technology to recreate the display as a wonderfully moving (in both senses) and truly sensational experience for visitors?

Armand D’Angour

Response for Retain:

Times do indeed change but conflating the mores of one era with another will not rectify the past. There are no uncertainties that Lord Elgin had authority from the Ottomans; these are just occlusions for a narrative.

The analogy of William the Conqueror tearing up Stonehenge does not work. Elgin was no looting conqueror but an ambassador and Hellenist. Britain has always been friends with Greece. More attention for preservation of other ancient sites could be paid instead of millions for one political project and anti-Elgin attacks.

Elgin intended to set up a private museum. The purchase by the government for ordinary people to admire ancient art set a pattern which opened up Classical learning. However, the dogma of national heritage chips away the social function of museums. The Acropolis Museum presents the development of Greek art, the British Museum exhibits world culture; both are centres of education yet their best interests will not be served by taking apart the most popular section of one collection. Nor is it fitting for both sides to be pitched in a re-enaction of the battle of Lapiths and Centaurs for the agendas of politicians, corporate bodies and rights lawyers – philistines who have nothing to do with culture. The Elgin marbles are for artists, scholars and those who love Ἑλλάς.

Can the museological display – whose ‘Cold Pastoral’ played unheard melodies and entwined the sublime iconography from the Parthenon frieze in the most awesome ode of the English language – really be described as “not very inspiring”?

Tista Austin

Response for Return:

It is easy to mock Byron’s lyrical outrage about Elgin’s despoliation of the Parthenon, but proponents for their retention in the British Museum are no less emotionally wedded to the myth that Elgin’s actions were not only legal but noble. If possession is nine tenths of the law, one wonders why retentionists bother to accord hollow claims of legality and scrutiny to the residual tenth. The fact that the law to prevent the return of the Marbles in the UK was proposed as late as 1963, and has since been used to toss the issue fruitlessly back and forth between the Government and the Trustees, highlights the legal fiction of the proposition that Elgin and the Museum ever had lawful title to the antiquities.

If indeed the intention had been to keep them, during the bitter travails of Greece’s struggle for independence, safe from damage and deterioration, honour and decency would require that the (not so) carefully conserved stones should now return to their original and proper home, with the Acropolis Museum now providing a safe and dignified future for them in their native Athens. Moreover, when that day comes it should be felt not as a loss but as a proud gain for both nations.

The return of the Parthenon sculptures, if not of other objects still on Elgin’s estate, will not only create space for a truly inspiring and imaginative display, it will be a welcome boost in this post-Brexit world to Britain’s moral self-image and international standing.

Armand D’Angour

Tista Austin grew up in Cambridge and is a teacher and poet. She studied Classics at University College London.

Armand D’Angour is Professor of Classics at the University of Oxford. He has written previously for Antigone on the music of Sophocles’ Ode to Man here, on the Song of Seikilos inscription here, on Sappho and Catullus here, and on a mysterious graffito at Abu Simbel in Egypt here.

What Did You Think?

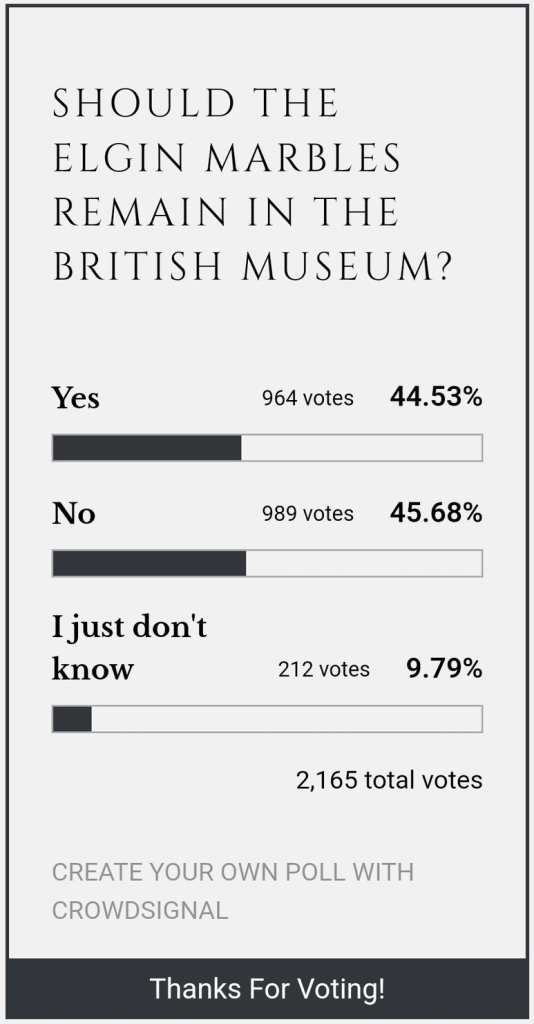

For the four days following the publication of this article, we conducted a poll on this page of what readers thought. The results were neck-and-neck throughout, ending with a slight advantage for “Return”. Thank you to the 2,000+ people who cast a vote:

Notes

| ⇧1 | William St Clair, Lord Elgin and the Marbles (Oxford UP, 1998). |

|---|