Jaspreet Singh Boparai

Part I of this essay can be read here, Part II here, and Part III here.

On 16 October 1840, Stendhal began writing a long letter to Honoré de Balzac thanking him for his warm, appreciative review of his novel The Charterhouse of Parma. He sent off a copy of the third draft on 29 October, in which he reveals how much he hated Count Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821), whom he loathed almost as bitterly as he did Chateaubriand.

Stendhal mentions Maistre disparagingly in The Red and the Black as the author of On The Pope (1819), a tract which even traditionalist Catholics tend to regard as potentially heretical, not on account of impiety, blasphemy or unorthodox religious opinions, but because it places so much authority in the hands of the pope. This appears to be the only one of Maistre’s works he knew, which is a shame: one has the sense that the two men would have enjoyed each other’s company, and gleefully joined forces to make people like Chateaubriand storm out of the room, because unlike him they did not take themselves so seriously.

Throughout the 19th century, Maistre was reviled for his sarcastic literary attacks on the French Revolution; his work has always provoked special outrage in uptight right-wing classical liberals of the more reactionary sort, including Viscount Morley (1838–1923), Sir James Fitzjames Stephen (1829–94), and above all Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909–97), perhaps because he mercilessly made fun of such men’s ideas about political constitutions.[1] Berlin in particular was driven to fury by him, to the point of Dostoyevskian paranoia. Maistre got under his skin, despite having died long before he was born.

In the English-speaking world, Maistre is arguably less well-known than his younger brother Count Xavier de Maistre (1763–1852), author of A Journey Around My Room (1794), a delightful spoof travelogue that he conceived whilst under house arrest in Turin for an illegal duel. Joseph de Maistre tends to be thought of as a mere political propagandist. In truth he is much less boring than that: he was perhaps the most awesomely learned man of letters of his era. Indeed, he succeeded where even Stendhal failed as an innovator in the classical tradition. Yet he thought of himself less as a writer than a reader.

Maistre was moderately liberal throughout his twenties and thirties, and does not seem to have bothered much about politics. He joined a Masonic lodge, mainly because all the interesting conversationalists in his city seemed to be there. His was the largest private library in the entire Duchy of Savoy. Wide, eclectic reading, particularly in Enlightenment philosophy and esoteric spiritual texts, as well as Renaissance-era antiquarian works in Neo-Latin, made him seem sinister to the authorities: when the French Revolution erupted in 1789, the President of the Savoian Senate suspected Maistre of secretly harbouring radical Jacobin sympathies.

In 1792, Maistre was compelled to flee from his home, and ended up spending a quarter of a century in exile, in Geneva, Lausanne, Venice, Sardinia and finally Saint Petersburg, where he lived from 1802 to 1816 as a diplomat for the Kingdom of Sardinia at the court of the Russian Tsar, who frequently intercepted his official correspondence, and was always delighted to read Maistre’s long, detailed, brilliantly-written dispatches to his slow-witted superiors. Maistre was a great success in Russia – perhaps a little too great: the Russian Orthodox Church objected to his success in convincing aristocrats to convert to Catholicism, and he was finally forced to go back home. He died in Turin in 1821.

Maistre’s Plutarch Translation

Most of Maistre’s literary work was published posthumously. He never conceived of himself as a writer: he was a jurist, a magistrate, a diplomat and (above all) a gentleman. Unlike most authors of his stature, he did not think that his writings would secure him fame or immortality. And yet he wrote almost as much as he read.

Throughout the 19th century, one of Maistre’s most popular texts was a translation of the Plutarch essay that is translated in volume 7 of the Loeb Classical Library’s edition of the Moralia as “On the Delays of Divine Vengeance”, but which Maistre rendered as Sur les Délais de la justice divine, dans la punition des coupables (On the Delays of Divine Justice in Punishing the Guilty). He completed this in 1810, and published it six years later; it went through 21 further editions or reprintings between 1822 and 1885.

This text, like Maistre’s 1812 Neo-Latin Animadversiones, has so far not received the scholarly attention that it deserves. Professional Classicists could learn a great deal from Maistre: his footnotes reveal an intimidating depth of learning, and his introduction is both elegantly scholarly and politely combative. He freely acknowledges the difficulty of Plutarch’s Greek, and the obscurity of some passages in the transmitted text; what will alarm some modern readers is his uncompromising position on theological and religious matters.

Plato was Maistre’s favourite pagan philosopher: he habitually read and re-read Platonic dialogues in Greek to the end of his life; yet in so many ways Maistre seems closer to Plutarch. Perhaps this led to wishful thinking: Maistre claims it not to be implausible that Plutarch, if not a Christian, was at least distantly familiar with Christianity, and might have known some of its doctrines. He makes an interesting case, to say the least. Is it convincing?

As for the translation itself: whilst it is scrupulously faithful to the content of Plutarch’s original (albeit with editorial additions to clarify certain passages), Maistre has transformed this text from a dialogue to an ordinary dissertation in prose. This is a striking alteration, in the context of Maistre’s own original literary work: Plutarch’s Moralia after all provided him with his preferred models for philosophical dialogue. Indeed, in the introduction to “On the Delays”, Maistre daringly ventures to suggest that this dialogue seems preferable to Plato’s Phaedo, at least where its most important content is concerned.

Plutarch’s “On the Delays” centres around a question that has perennially preoccupied philosophers and theologians, not least in Christian societies: if the world is justly governed, why does so much evil seem to go unpunished? Maistre asked himself this repeatedly throughout a quarter-century of wandering around the world, far away from his home and family.

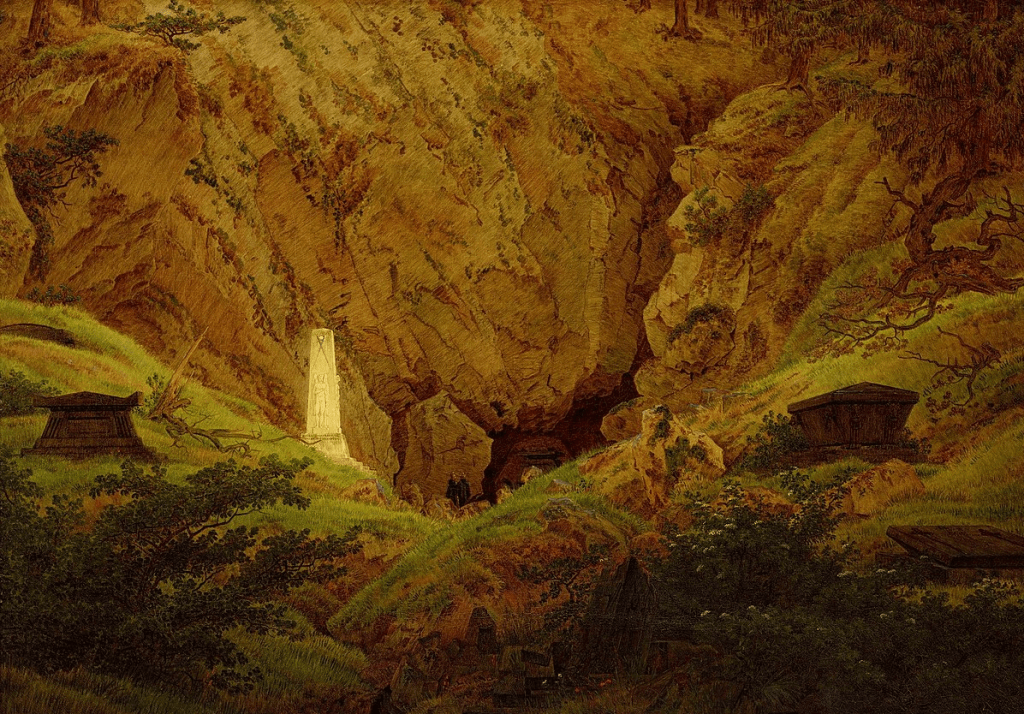

Plutarch ends his dialogue with the story of Aridaeus, a profligate young man who spent three days in a coma after a fall, and only regained consciousness during his own funerary rites. Whilst he was dead to the world, he had a vision of the afterlife, and the punishments endured by those who are guilty of crimes, that scared him straight: he lived the rest of his days as an example of justice and piety. This invented myth is elaborate, evocative and vivid; perhaps it recalls Book VI of the Aeneid even more than anything in Plato.

The philosopher David Hume (1711–76) loathed “On the Delays”, singling it out as one of only two of Plutarch’s works deserving ridicule: “It is also writ in dialogue, contains like superstitious, wild visions, and seems to have been chiefly composed in rivalship to Plato, particularly his last book De Republica [i.e. The Republic].” In the footnotes to his translation, Maistre snidely congratulates Plutarch for provoking Hume and causing him to lose his composure for once.

This translation received a mixed review from the American aristocrat John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), who served as United States Minister to Russia between 1809 and 1814, just over a decade before he was elected sixth President of the United States on 9 February 1825.[2] His journal for 16 August 1811 records:

I received a note from Count Maistre [sic], the Sardinian minister, requesting me to return his manuscript translation of Plutarch’s treatise on the Delays of Divine Justice which he lent me some weeks ago. I have read it, and been pleased with the preface and notes. The translation is much too dilated. The argument against [David Albert] Wittenbach [editor of the 1795 Oxford edition of the Moralia], to prove that the Christian Scriptures were known to Plutarch, is weak.

He commends Wittenbach’s learning and ingenuity, and censures his infidelity. There are two points in the character of Plutarch’s style which the French denominate bonhomie and naïveté: they are well-represented in the old [1572] translation of [Mgr Jacques] Amyot [(1513–93)], but I do not find them in that of Count Maistre. He has doubtless corrected some mistakes and elucidated some obscure passages. Plutarch reasons well, but leaves much of the mysterious veil over his subject which nothing but Christian doctrine can remove.[3]

The politely simmering disagreement between Maistre and Adams may have involved more than literary style: Adams was a Unitarian Christian, which is to say that he believed in God (and indeed was steeped in the Bible, which he studied every day), but rejected the conception of God as Father, Son and Holy Ghost that continues to be taught in most churches. No wonder he found Maistre’s firmly Catholic reading of Plutarch unconvincing. Yet perhaps he had a point, when he called the translation “much too dilated”.

Unlike Stendhal, Maistre was more interested in Plutarch’s Moralia than the Parallel Lives, of which his favourites were the early, quasi-mythical ones: Solon, Numa, Theseus, Lycurgus. This deep affinity with the more mystic, mythic, religious aspect of Plutarch’s oeuvre ultimately inspired Maistre’s single most important literary achievement, which begins from the same question as “On the Delays”: why does so much evil seem to go unpunished?

An Ancient Symposium, without the Wine

Maistre’s masterpiece, the Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg (The Saint Petersburg Dialogues) seems to have been essentially complete by April 1813, but was left unfinished at his death (the final section breaks off before the end). This is a philosophical dialogue that is so richly characterised and imagined as to qualify almost as a novel. Indeed, it may be considered the finest single piece of prose in the French language between Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ 1782 libertine novel Dangerous Liaisons and Stendhal’s The Red and the Black.

For our purposes this text is worthy of attention as the most original and brilliant exercise in classical reception of its times. There is nothing else like it in modern literature; in some ways it perfectly exemplifies the ‘romantic’ aesthetic that Stendhal tried to delineate in Racine and Shakespeare. Indeed, it arguably does so even better than any of Stendhal’s own novels. This is not to say that it necessarily surpasses them as a work of art – but the achievement seems at least as great. The two men may have been more or less equal in literary genius, even if Stendhal’s narratives are on a grander scale.

The Saint Petersburg Dialogues is a philosophical work in the tradition of Cicero, more than of Plato (or even Plutarch). There are three characters: the Count, who is a stand-in for Maistre himself; the Senator, a reactionary, deeply pious mystic who is close to the Russian Tsar; and the Chevalier, an aristocratic French émigré in his twenties who has become a career soldier. According to Maistrean family lore, the Senator was based on Count Tamara, a Russian Privy Councillor who was especially fond of Joseph de Maistre during his years in Saint Petersburg, and shared many of his intellectual interests; as for the Chevalier: he has not yet decisively been identified, despite Maistre’s vivid, convincing representation of his personality.[4]

Dramatically, the Dialogues unfolds mainly in the library of the Count’s small riverside villa outside Saint Petersburg on a dozen or so successive evenings during July 1809. The three friends are quietly enjoying the sunset on the river as they travel by boat to the Count’s house when the Chevalier breaks the silence:

“I would like to have here in this boat with us one of those perverse men born for society’s misfortune, one of those monsters that weary the earth…”

And what would you do if he accommodated you? This was the question that the two friends asked, speaking at the same time. “I would ask him,” the Chevalier replied, if the night appeared as beautiful to him as it does to us.”

The Chevalier’s exclamation pulled us out of our reverie. Soon his original idea engaged us in the following conversation, of which we were far from foreseeing the interesting consequences.[5]

From then on, the discussion circles around issues of Providence, and God’s justice, beginning with the apparent mysteries involving “the happiness of the wicked and the misfortunes of the just”. But to describe the Dialogues thus is to make the work seem dull, dry and churchy; whereas the book is absorbing, and bewitching – and virtually amounts to a classical education in itself.

Two of the three friends are staggeringly well-read, not least in Classical Greek and Latin books. The Chevalier is there mainly to listen and learn; the Count and Senator tease him politely for his allegedly shaky command of Latin. A single page or speech from the Dialogues could easily be used to assemble an undergraduate syllabus.

For example: in the second evening’s conversation, the Count makes a speech on the concept of Original Sin that effortlessly, elegantly brings up Cicero, Seneca, Ovid, Plato, Aristotle, the Epistles of Saint Paul, Saint Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana and various books of the Old Testament, to name only the books that Maistre absorbed in Greek and Latin. All this in the space of a few pages, before the Count moves on to the antiquity of the Etruscans and the astronomical knowledge of Archaic Greeks and Egyptians.

From there the Count passes through Plutarch’s On Isis and Osiris and admits that The Banquet of the Seven Sages (Plutarch’s most impressive literary recreation of a symposium) makes him wonder whether the Ancient Egyptians knew the true form of planetary orbits; he speculates further on the mysteries of the pyramids, and the potential connections between Greek deities and ancient Indian traditions: he even refers to the Hindu god Krishna as “the Indian Apollo”. All this in a few hundred words.

Even a short summary of the Dialogues would consume a great deal of space. The sheer range of topics and materials covered is dizzying. It seems impossible that anyone could have so much knowledge, classical or otherwise, at his fingertips; Maistre shows us that this level of learning is possible even in those who are neither neurotic nor awkwardly eccentric. He is attempting to memorialise the entire tradition of French aristocratic salon culture as he experienced it before being forced to move to Russia.[6]

The codes and conventions of the old-fashioned salon compel Maistre to wear his learning lightly, without ever seeming obsessive, pedantic or condescending. His good manners are not the result of memorising a book of rules; rather, they have been polished and refined through continual use. Or so he hopes. Part of the Count’s underlying sadness in the Dialogues comes from the realisation that erudite, allusive intellectual conversations of the sort that he took for granted before the Revolution are hard to come by in exile, even in ‘polite society’.

How Do You Revive Cicero?

In the eighth conversation, the Chevalier admits that he has been taking notes on these discussions every night after returning home, and would be happy to publish a record of them one day; the Count and the Senator scoff good-naturedly at the idea. This enables the Chevalier to try to defend the literary form of The Saint Petersburg Dialogues:

The Chevalier: …Since you have both involved me in serious reading, I have read Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, translated into French by Président Bouhier and Abbé d’Olivet. This is still a work of pure imagination, and gives no idea of a real entretien. Cicero introduces a listener whom he designates simply by the letter A; he has a question raised by this imaginary auditor, and answers him with a regular uninterrupted dissertation. This cannot be our genre either. We are not capital letters; we are very real, very palpable human beings. We are talking to instruct and console each other. There is no subordination among us; and despite your superiority of age and knowledge, you have accorded me an equality I did not request. So I persist in thinking that if our entretiens were faithfully published, that is to say with all the exactitude possible… Senator, why are you laughing?

The Senator: I am laughing because it seems to me, in effect, that without perceiving it, you are arguing powerfully against your project. How could you more clearly demonstrate the embarrassment that it would involve than by leading us into a conversation on conversations? Would you also, by chance, want to record this one?

In this conversation, Maistre playfully yet unobtrusively reveals the ways in which he is renewing his Ciceronian inspiration. Cicero may be the principal model for the Dialogues, even more than his beloved Plutarch; but Maistre’s reception is clearly ‘contaminated’.

Formally and linguistically, the Dialogues is quite deliberately artificial, as Cicero’s dialogues seem (certainly when compared to Plato’s). Yet there is no stiffness: every conversation gives off a startling impression of real life. In this way, Maistre may even vindicate the practices of the less intelligent and original ‘classicists’ attacked by Stendhal, even if he might have been the only writer in his age to have used these particular literary devices and succeeded artistically. But this might be because, as he grew older, Maistre preferred to ignore modern literature and immerse himself directly in his Greek and Latin antecedents. Why bother with imitations when you could have access to the real thing, in the original language?

For all the author’s learning, The Saint Petersburg Dialogues has an easy, natural flow: you do not need to know very much about Maistre’s classical sources and references to enjoy the conversation. Some of Maistre’s work (for example, the 1809 Clarification on Sacrifices, published as an appendix to the Saint Peterburg Dialogues, is forbiddingly learned and footnote-heavy). But classical learning is ultimately less an end in itself for him as a resource that feeds his imagination, and enables him to come up with startling images and metaphors, as in this well-known passage from the end of the eighth dialogue:

A perfectly accurate idea of the world can be formed by seeing it under the aspect of a great natural history museum overturned by an earthquake. The door is open and broken; there are no more windows; entire cupboards have fallen over; others are still hanging by their fasteners, ready to let go. Shellfish have rolled into the mineral room, and a bird’s nest rests on the head of a crocodile. Nevertheless, what idiot would doubt the original intention, or think that the building was constructed in this state? All the great parts are together; the entire thing can be seen in the least splinter of glass; the emptiness of a chest fills it; order is as visible as disorder, and the eye, in looking over the vast temple of nature, easily re-establishes everything that some dangerous agent has broken, falsified, soiled, or displaced. There is more: look closely, and you will recognise a restoring hand. Some beams are propped up; some routes have been laid out amidst the wreckage; and in the general confusion a host of equivalents have already taken their places and are in contact. So there are two intentions visible instead of one, that is to say, order and its restoration. Limiting ourselves to the first idea, disorder necessarily supposing order, the one who argues disorder against the existence of God, assumes order to combat it.

Part of the reason we hear so little about The Saint Petersburg Dialogues even as an exercise in the classical tradition is that Joseph de Maistre offends the sensibilities of most university academics, not merely because he is so much better-informed about classical literature than the average Regius Professor, but on account of his sincere, devout Christianity. This is a crime they cannot forgive.

The Count’s glowing praise of Seneca towards the end of the ninth dialogue inevitably leads into speculations about Seneca’s Christianity (although, unlike the Senator, is politely sceptical about the supposed correspondence between Seneca and Saint Paul). But the Count’s (or Maistre’s) views on Vergil’s fourth ‘Messianic’ eclogue will really make most professional Classicists need a change of clothing. The fact that he says these things with a serene smile on his face causes these people to howl, and not with laughter. Perhaps this makes his Dialogues an exemplary model for the classicising writers of the future. He reminds the mediocre that they have achieved nothing of lasting value, or even fleeting beauty, and never will.

Who Was Right?

Ultimately, the point of studying classical reception and the classical tradition is instrumental. Greek and Latin literature and art are inexhaustible; nobody has really managed to supersede the ancient historians or philosophers, beyond a certain point; the languages themselves are sacred, at least to Christians, since Greek, Latin and Hebrew are present on the Cross itself, at the focal point of history, on the sign that Pontius Pilate had affixed over Jesus’ head proclaiming who He was. But none of this can be taken for granted; a tradition requires constant maintenance, just like everything else of value, or else it falls into ruin.

Chateaubriand shows us the charm and the beauty of ancient poetry; Stendhal tries to find inspiration in history, and the great men of the past; Maistre decides to make his own classical philosophical dialogue, and miraculously succeeds. Maistre tried to rebuild structures that were ruined in 1789; Chateaubriand decided to enjoy the ruins as ruins, presuming that he was one himself; Stendhal saw, not necessarily ruins, but part of a process that provided a building-ground for the future – until he too saw that these were indeed ruins.

All three men began from positions that were at least moderately pro-Revolutionary, and none ever lost his fascination with Napoleon, even when it mingled with disappointment, disgust or horror. All had occasion for second thoughts about their uncritical youthful embrace of Plutarch, once they gained first-hand, real-life experience of what great men do, and what they are like.

Maistre is the most learned of our three romantic classicists (or classical romantics), and his Saint Petersburg Dialogues is an unqualified success formally, stylistically, intellectually and artistically. Where the classical tradition is concerned, his only issue, in a practical sense, might be that he sets an example that is difficult to follow, even for those who have a similarly unique, idiosyncratic temperament. In many ways he is like a Catholic Nietzsche (albeit without Nietzsche’s unevenness, bad manners, anti-Christian attitudes or blithe tolerance for cruelty).

Also, his work is necessarily of limited reach: even though he writes charming and accessible prose, he is demanding, by sheer virtue of the fact that he is not a storyteller. On the other hand, his work has considerable philosophical value. Perhaps he is fated to remain a writer’s writer, like the Plutarch of the Moralia, or the Seneca of the Quaestiones Naturales (both of these works were among his favourites). You can learn from him; but would you want to copy his example? This is an open question, obviously.

Chateaubriand, unlike Maistre, is thoughtless about the classical tradition. This is not a censure, although it is true that he quite literally venerates Latin and Greek writers in the way that Catholics are supposed to venerate saints. He does not seem to recognise them as flesh-and-blood people, or take a critical attitude towards the ancient literature that they created.

To him the entire classical heritage is a seamless whole, and he rarely discriminates when alluding to or borrowing from some ancient source. For him, Homer’s Odyssey and Fénelon’s Télémaque are one and the same, and probably confused somewhat with Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, because he sees no difference between a 17th-century novel and an Archaic Greek poem, once he is told that both of them are, in some sense, ‘classics’.

Chateaubriand is without question a great writer; is his literary greatness purely a matter of style? It is difficult to separate his writing from his enormously interesting life: he seems to have become a great man almost in spite of himself. Perhaps that means he is not truly a great man, since great men are, by definition, worthy of emulation. Then where does that leave Napoleon? Clearly these questions were easier to answer in Plutarch’s day.

As for Stendhal, we have to ask ourselves – where the classical tradition is concerned – does he shed any light on it, or refresh our views on ancient art, literature or history, or inspire us to revisit our Greco-Roman heritage? He was inspired by the idea of Classics, but did not have the patience to sit down and apply himself to serious study, of classical literature, or anything else. Yet he so often sounds like an expert, despite his frequent lack of expertise. Being a genius, he never had to work very hard for brilliant insights; but his gifts were unpredictable, and unreliable, and always threatened to abandon him if he became too self-conscious.

This might be why Stendhal was so much better as an art critic and a writer about music than as a theorist or commentator about the literature of any period. He loved talking about books, but did not really have the attention span to read for very long after he thought he had got the gist of a given writer. His real interest was in expressing himself; at least he was sufficiently sensitive to find something to discuss after spending twenty minutes looking at an Ancient Greek statue or Renaissance painting.

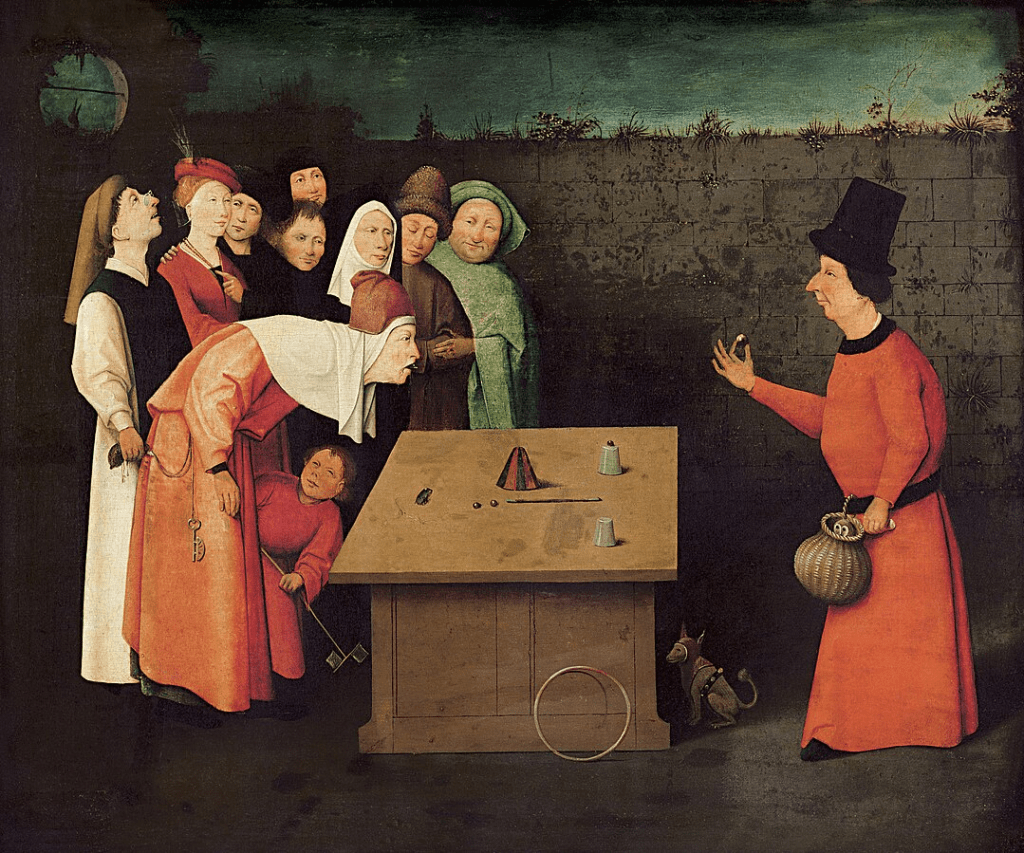

His criticism is ultimately self-serving, of course. He was against ‘classicism’, whatever it was, because he did not have the self-discipline for it. Luckily for him he was granted rare gifts that enabled him to transcend his personal defects, because for all the wisdom, insight and shrewdness in his narrative writing, his criticism sets a terrible example that nobody should follow. Those of us who love him concede that you should take everything he says with a pinch of salt, and treat him as you would a charmingly effective fraudster.

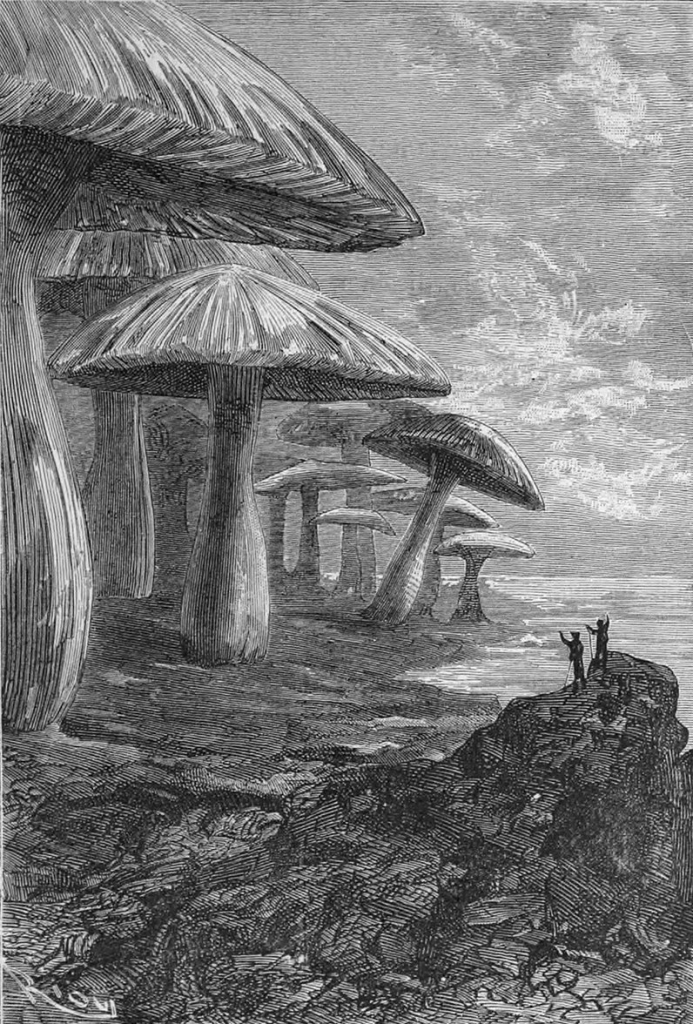

Jules Verne’s 1864 novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth begins when a German professor comes across a coded message in a manuscript. He and his nephew try to decipher it: the script is Runic, but the message is in Latin:

In Sneffels Joculis craterem quem delibat

Umbra Scartaris Julii intra calendas descende,

Audax viator, et terrestre centrum attinges.

Quod feci, Arne Saknussemm.

According to the translation by Frederick Amadeus Malleson (1871) these words may be rendered into English as:

Descend, bold traveller, into the crater of the jokul of Sneffels,[7] which the shadow of Scartaris touches just before the Kalends of July, and you will attain the centre of the earth; which I have done. Arne Saknussemm.

Arne Saknussemm is allegedly a 16th-century alchemist. The Professor and his nephew head straight to Iceland as fast as they can to follow in Saknussemm’s footsteps and reach the centre of the earth.

This is how the classical tradition ought to function, at a metaphorical if not a real-life level. Someone has been there before and is showing or telling you how to get there; you should waste no time and go. Really, this is what Joseph de Maistre does in his Saint Petersburg Dialogues: he is the alchemist who knows how to get to the heart. Of all the great writers of the Romantic period, he may be the only one who got the classical tradition absolutely right, and in doing so, created an authentic ‘classic’.

Jaspreet Singh Boparai recently abandoned academia to cultivate the Muses. He has previously written for Antigone on Tacitus and the thrill of writing here, on the challenges of translating (pseudo-)Latin here, on the pleasures of Poussin here, on Neo-Latin syphilis here, on Apuleius the ‘witch’ here, on V.S. Naipaul and Latin here, and on the Classics and British India here.

Further Reading

Joseph de Maistre

Richard Lebrun, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Manitoba, has tirelessly edited, translated and commented on Maistre’s work, and made a great deal of it available to an English-speaking readership: his 1993 edition of the Entretiens, which is entitled The St Petersburg Dialogues; Or, Conversations on the Temporal Government of Providence (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 1993; reprinted 2020) is as essential to read as Stendhal’s novels. Start with this and proceed from there.

Those whose interests are less literary and more political may freely obtain a PDF of the 2020 edition of Maistre’s Essay on the Generative Principle of Political Constitutions (1814) from the European Parliament-funded New Direction Foundation here. But political philosophy can make one’s head hurt even when written by as masterly a stylist as Joseph de Maistre.

You should avoid the anthology of Maistre’s writings that was edited by Jack Lively, Professor Emeritus of Politics at Warwick University (The Generative Principle of Political Constitutions: Studies on Sovereignty, Religion and Enlightenment, Macmillan, London, 1965; reprinted in 2017 by Routledge). The translation is stiff, awkward and tuneless; even worse, the unfortunately-named Professor Lively has tried to transform Maistre’s writings into something like a Powerpoint presentation, and edited out all the literary content that is the main reason to read Maistre’s work in the first place. The bureaucratic-style philistinism is hard to forgive. Professor Lively cites Viscount Morley’s essay on Maistre in a footnote early in his introduction, then proceeds to help himself, not only to His Lordship’s content, but also his ideas. The tone of suppressed indignation that mars the introductory essay might have appeared more convincingly virtuous had there been less shoplifting.

If you have French, Éditions Robert Laffont has produced a splendid collection of Maistre’s major works, edited by Professor Pierre Glaudes of the Sorbonne (Paris, 2007). The commentary and editorial supplements are invaluable for non-specialists. Also worth adding to your library is Maxence Caron’s beautiful edition of Maistre’s correspondence (Éditions Belles Lettres, Paris 2017), which is of particular interest not least because Tolstoy considered these letters a key resource when he was researching War and Peace (1869). The communications from Saint Petersburg to his distant family are particularly moving, whilst the diplomatic correspondence can often prove astonishingly sharp.

For an example of Maistre at his worst, Classiques Garnier in Paris reprinted Jules d’Ottange’s 1918 edition of Du Pape in 2021 in an inexpensive edition; this will help you understand why Stendhal loathed him so. On the other hand, Chapter Twenty of Book One features a defence of the Latin language that is far more convincing than the ones we usually hear from tenured lecturers in Classics departments who claim to be nervous about losing their jobs.

The Maistre Controversy

We cannot avoid mentioning Isaiah Berlin’s 1990 essay “Joseph de Maistre and the origins of Fascism”, which was first published in the New York Review of Books, and has been collected in The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas (edited by Henry Hardy; John Murray , London, 1990; 2nd ed., with an introduction by John Banville, Princeton UP, 2013).

Berlin seemed like a hero to many intellectuals during the Cold War, and into the 1990s. This essay helps demonstrate why nobody under 50 seems to know or care who he is. He has taken two of the Senator’s speeches from The Saint Petersburg Dialogues and tried to pretend that they accurately represent Maistre’s own settled opinions, then extrapolated idly from these two speeches in an attempt to paint Maistre as a precursor to barbarous 20th-century ideas.

Laziness, deceit or both? The reasons no longer matter. Even those of us who used to admire Berlin without reservation will concede that something about his grandly ‘literary’ essays smells fake. One reason to develop a sense of ‘taste’, aesthetic or otherwise, is to be able to sniff out this sort of thing efficiently.

I, for one, am grateful to Berlin. Had I not stumbled across his essay, I might never have heard of Maistre at all, or been alerted to this sort of thing in the rest of his work. You might as well read “Joseph de Maistre and the origins of Fascism”, if only as an example of an extinct style of 20th-century pseudo-classical rhetoric.

The journalist H.L. Mencken (1880–1956) once described the oratory of President Warren G. Harding (1865–1923; presidency 1921–3) as akin to “a hippopotamus struggling to free itself from a slough of molasses”. Perhaps Berlin’s writing is not that bad, but when you have read a few pages of his ‘literary’ prose, you begin to wonder whether he wrote it whilst wearing a powdered wig.

Perhaps the Maistre essay is a proxy attack on some political contemporary figure who really was odious. If so, Berlin was in a position to attack directly, and should have had the courage to do so.

Notes

| ⇧1 | For a taste of this, see Maistre’s 1814 Essay on the Generative Principle of Political Constitutions, which has recently been republished online in a serviceable, well-presented downloadable edition. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Because no presidential candidate won a majority of votes in the Electoral College in the initial election (26 October–2 December 1824), the House of Representatives held what is known as a ‘contingent election’ on 9 February 1825. This was one of the more interesting elections in American history, for a number of reasons that are far beyond the scope of this essay… |

| ⇧3 | See the first volume of the 2017 Library of America edition of John Quincy Adams’ Memoirs, edited by David Waldstreicher. |

| ⇧4 | See the introduction to Richard Lebrun’s translation of the Dialogues (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 1993; reprinted 2020). |

| ⇧5 | Quotations are taken from Richard Lebrun’s translation. Lebrun’s commentary in particular is outstanding. Maistre’s prose is difficult to render into English: whilst lacking the musical qualities of Chateaubriand, it has its own unique rhythms and sonorities that cannot be exported from French, even by someone who knows Maistre’s oeuvre as thoroughly as Lebrun does. |

| ⇧6 | For an introduction to this culture, see Benedetta Craveri’s The Age of Conversation, published in English translation in 2005 by New York Review Books. |

| ⇧7 | Snæfellsjökull, in Iceland. |