Jaspreet Singh Boparai

Part I of this essay can be read here.

The Romantic Classicist

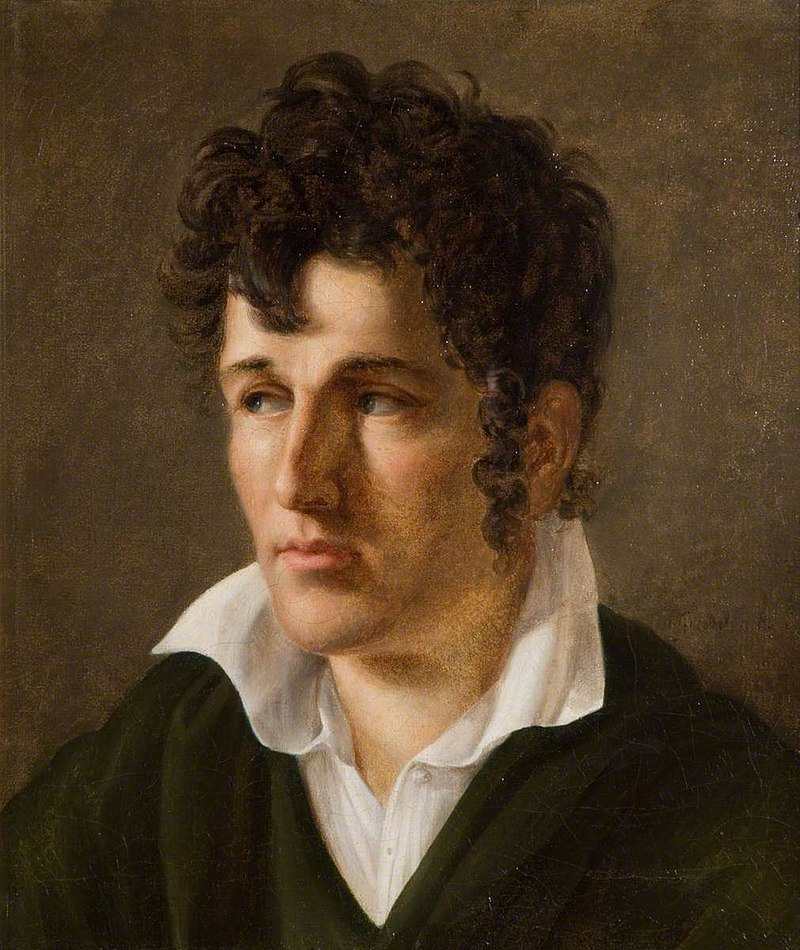

Unlike Stendhal, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–48) did not have a particularly original or brilliant mind. In intellectual terms, at least, nobody could think of him as a genius. Yet unquestionably he was a great writer. Alas, his work does not translate well into English: there is a rhythm and music to his prose that simply cannot be carried across into another language. As he himself says, in a digression on English literature in his Memoirs From Beyond the Grave (Book 12, Chapter 3):

No one, in a living literature, can be a competent judge except of works written in his own language… When an author’s chief merit is his diction, a foreigner will not fully comprehend this merit. The more intimate, individual and national a talent, the more its mysteries escape the mind which is not, so to speak, a ‘compatriot’ of this talent. We admire the Greeks and Romans by hearsay. Our admiration comes to us from tradition, and the Greeks and Romans are not here to mock our Barbarian judgments. Who among us can form any idea of the harmonies of Demosthenes or Cicero, the cadences of Alcaeus or Horace, as they must have sounded to a Greek or Latin ear? It has been claimed that true beauty is for all time and all nations: yes, if we are speaking of the beauties of feeling and thought; but no, not the beauties of style: style is not, like thought, cosmopolitan: it has a native soil, sky and sun of its own.[1]

Few (if any) living English writers could get away with writing like this. When translated, Chateaubriand sounds long-winded and often vapidly self-absorbed. There is some truth to this; and yet his Memoirs from Beyond the Grave (first published in 1848, shortly after the author’s death) is a must-read in any language.

Chateaubriand’s only real subject was himself. His masterpiece is possibly his Vie de Rancé (1844), which is purportedly a biography of Fr Armand de Rancé (1626–1700), a wealthy, dissolute aristocrat who was ordained a priest but did not take his vows seriously until the death of his mistress in 1657. Fr de Rancé reformed his life, became renowned for his strict, severe, penitential discipline, and founded the Trappist order of monks. Yet somehow Chateaubriand succeeded in making this biography largely about himself instead of the abbé. The reader does not mind.

Narcissists and egotists can be as fascinating to us are they are to themselves, as long as they are charismatic, attractive and charming, and particularly when they lead lives that are as exciting and historically pivotal as Chateaubriand’s. Politically he always thought of himself as a reform-minded liberal, albeit with strongly conservative instincts and emotional attachments. Yet as a writer Chateaubriand reveals himself to be an accidental, unconscious reactionary.

He watched with great interest and curiosity as the ground shifted beneath his feet, and had no idea how to illuminate these radical changes in his literary work. He was too unreflective, in the sense that he rarely examined or questioned his assumptions. Unlike many of the other noblemen among his contemporaries, he was unafraid unintentionally to reveal himself in what he wrote, even where the revelations did nothing to flatter him. In other words, he was a ‘Romantic’, in the same way in which the greatest English poets of the early 19th century were, even if he tried consciously to reject the aristocratic radicalism of Byron and Shelley.

Chateaubriand was a product of 18th-century classical culture: whilst not particularly scholarly or erudite, he was steeped in Latin literature to the point where he was scarcely aware when stray lines of Horace fell from his mouth. This was as his mother wanted him to be (Memoirs, Book 1, Chapter 6):

My mother had never given up her desire that I be given a classical education. She said that the sailor’s life for which I was destined “would not be to my taste”. It seemed to her a good thing, in any event, to prepare me for another career. Her piety led her to hope that I would decide on the Church. She therefore proposed to send me to a school where I could learn mathematics, drawing, fencing and English; she did not mention Greek and Latin for fear of agitating my father; but she reckoned that I could be taught these languages in secret at first, and in the open once I had made some progress. My father agreed to the proposition, and it was decided that I should be sent to the Collège de Dol.

In the first chapter of Book 2 of the Memoirs, Chateaubriand describes his education in some detail. He excelled in Latin, except that his prose compositions always seemed to fall naturally into pentameter verse, which led to his acquiring the nickname “The Elegist”, first with his Latin master, then with the entire school.

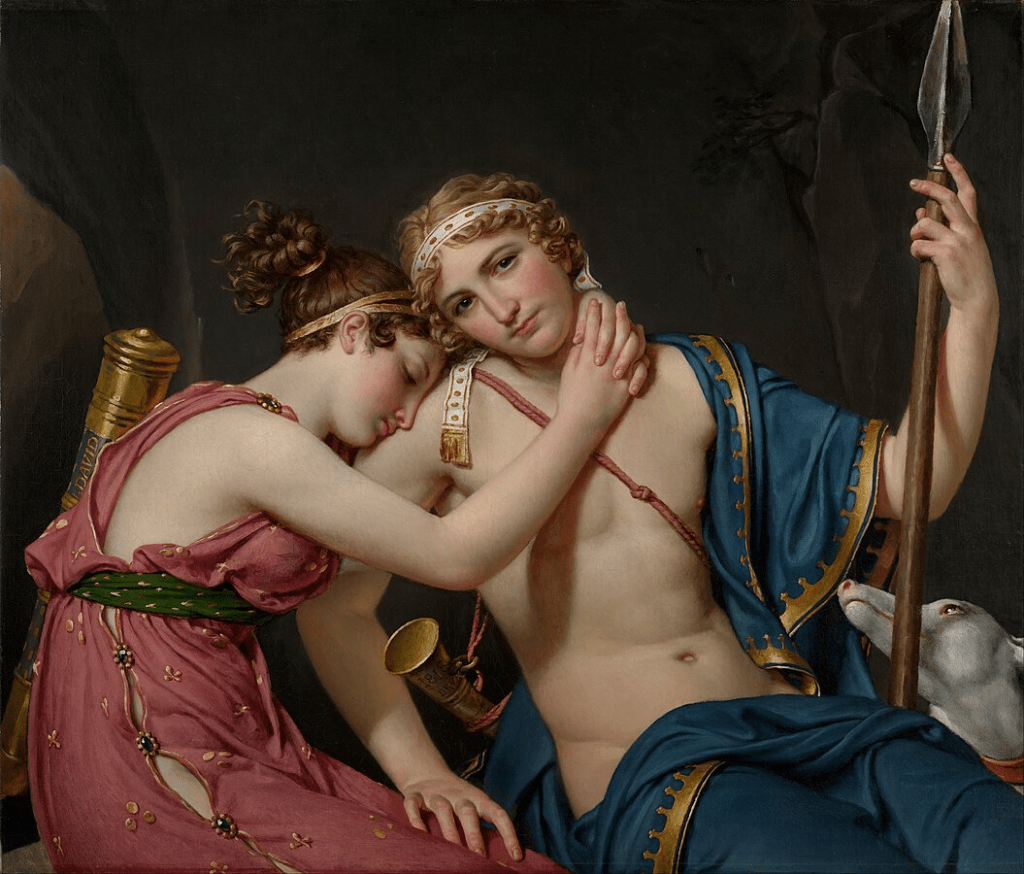

Soon Latin literature began to give shape to his emotional life. An unexpurgated volume of Horace gave him ideas about women that had never occurred to him; when he construed Book 4 of the Aeneid he began to suffer the thrill of an imaginary passion with Dido. He had a similar fantasy about Eucharis, one of the nymphs who serves Calypso and falls in love with Odysseus’ son Telemachus in Les Aventures de Télémaque (1699), a still-popular didactic novel by Mgr François de Salignac de La Mothe-Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai (1651–1715).

Fénelon (as the archbishop is commonly known) is one of the more complex figures of the Grand Siècle; his novel, whilst dated in some respects, remains absorbing, and fascinating on multiple levels, not least as an imaginative exercise in classical reception. But young Chateaubriand was not concerned as a schoolboy with the dynamics of Fénelon’s complex interplay with ancient literature and contemporary politics:

One day I translated on sight Lucretius’s Aeneadum genetrix, hominum divumque voluptas, ‘Mother of Aeneas’s sons, voluptuous delight of men and gods’ with such ardour that M. Égault tore the poem from my hands and set me to studying Greek roots. I palmed a copy of Tibullus, and when I reached Quam juvat immites ventos audire cubantem, ‘what joy to hear the wild winds as I lie here’, the sensual pleasure and melancholy of these verses seemed to reveal to me my true nature. (Book 2, Chapter 2)

Chapter 7 of Book 3 of the Memoirs is entitled “First Breath of the Muse”. Chateaubriand’s beloved elder sister Lucile (1764–1804) was the first to suggest to him that he had a gift for poetry; the second was his friend Louis-Marcelin de Fontanes (1757–1821; known from 1817 as the Marquis de Fontanes), who told him that he could compose in verse and prose equally well:

But this talent that a friend foresaw, has it ever really come to me? How many things have I waited for in vain! In the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, a slave is posted as sentry on the roof of the palace of Argos; his eyes scan the horizon in search of the signal fire that will announce the fleet’s return; he sings, to solace himself in the tedium, but the hours go by, the stars go down, and the torch never shine. When, after many years, the signal’s belated light appears over the waters, the slave is bent beneath the weight of time. Nothing remains to him except to reap misfortune, and the chorus tells him that “an old man is but a shadow wandering in the light of day”, ὄναρ ἡμερόφαντον ἀλαίνει [Aeschylus, Agamemnon 82].

A pedant would object that Chateaubriand has embellished the Agamemnon, and probably conflated elements of a commentary or translation with his own embroidered, faulty memories of the text. But this short passage deserves a commentary of its own for what it reveals of Chateaubriand’s creative talents, and the way in which his imagination is anchored (if not rooted) in his classical reading, and guided by ancient precedents, which are predominantly poetic. His soul resisted plain prose.

At thirteen, Chateaubriand began attempting to write in earnest: his first literary efforts were guided by Lucile; together they attempted translations from Lucretius and the Book of Job (in Saint Jerome’s Latin version) before cautiously expressing themselves in their own words. A few years later (Book 4 Chapter 8), Chateaubriand would spend his mornings in Paris translating Homer’s Odyssey and Xenophon’s Cyropaedia into French when he ought to have been trying to establish himself professionally. His elder brother despaired of his apparent idleness, not realising that Chateaubriand was laying the foundations for his future fame with these exercises.

Chateaubriand’s attraction to classical literature was fundamentally emotional: it was a part of his bond with his mother, no less than his unorthodox, highly aesthetic approach to Christianity must have been. When he was writing his Memoirs and had reached the point in his life where his mother died whilst he was in exile (Book 11, Chapter 4), Chateaubriand learnt of the death of his friend the Marquis de Fontanes, who had always encouraged him. Naturally, this reminded him of Lucile’s passing too. Unable to express all of this compounded grief in his own words, he quoted Catullus 65:

alloquar, audiero numquam tua facta loquentem

numquam ego te, uita frater amabilior,

aspiciam posthac? at certe semper amabo…

Alex Andriesse translates his translation thus:

“Am I never to speak to you again? Never to hear you speak? Am I never to see you again, O my brother more dear to me than life itself? O, but I shall love you forever!”

Latin poetry really was inextricable from his experience of life.

The Limits of Romantic Classicism

Chateaubriand’s wide reading of ancient literature, and unreliable yet impressive memory for stray minutiae, colours and flavours his prose in unexpected ways, as in this passage from his description of his home (Book 1, Chapter 4):

Finally, in order to omit nothing, I should recall the mastiffs that formed the garrison of Saint-Malo. These were descended from those famous dogs raised among the regiments of the Gauls which, according to Strabo, charged in battle formation with their masters against the Romans. Albertus Magnus, a Dominican monk and a writer just as weighty as the Greek geographer, recorded that in Saint-Malo “the protection of so important a place was entrusted each night to the loyalty of certain mastiffs that served as an effective and valuable patrol.” In my day they were condemned to death for having had the misfortune to snap unthinkingly at the legs of a gentleman, an incident that gave rise to the song “Bon Voyage”. All the dogs are mocked; they are imprisoned as criminals; one of them refuses to take food from the hands of his weeping master, and the noble animal is left to die of hunger. Dogs, like men, are punished for their loyalty. Once the Capitol, like Delos, was also guarded by dogs, who did not bark when Scipio Africanus came to offer his prayers at dawn.

The anecdote about Scipio Africanus comes from Aulus Gellius (6.1). There is no reason to suspect that Chateaubriand read authors like Pliny, Strabo and Aulus Gellius all the way through; it seems more reasonable to presume that he browsed occasionally in these texts, usually in translation, when he had a few moments to spare. He lived a busy life, and did not really have the time (or the temperament) for the sort of ambitious scholarship that he sometimes dreamed idly of accomplishing. For an idea of the limits of his learning, have a look at the book that made him famous, La Génie du Christianisme (‘The Spirit of Christianity’, 1802), which often seems like a shallow compendium of other people’s knowledge.

Chateaubriand’s attraction to classical literature cannot be isolated from his Christian, French, aristocratic notions of culture. Latin was simply an element in the atmosphere – part of the air he breathed, as it were. Because he was in a position to take its ubiquity for granted, he rarely studied any ancient text in depth. This is not in itself a problem, but it means that he was intellectually ill-prepared for the circumstances in which he found himself.

He could find solace or amusement in elegiac poetry, anecdotes about great men, or fascinating historical minutiae; on the other hand, he was unable to transform what he knew of ancient history and classical philosophy into something like a coherent view of the world. Whether this was the result of a failure of imagination, some unfortunate gaps in his reading, or both, is not for us to say.

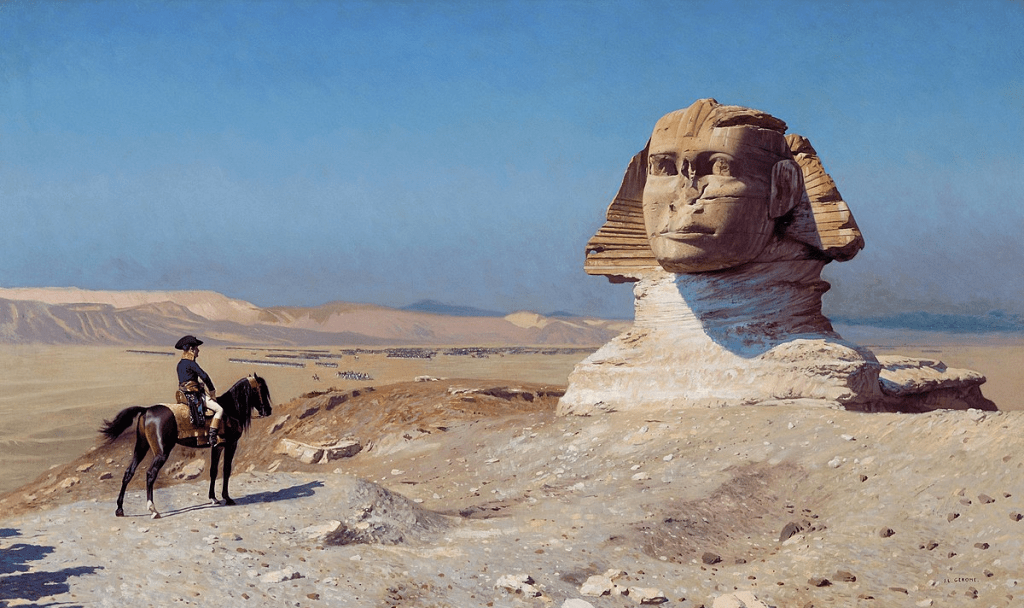

At most points in history one can get away with not thinking about these matters; yet Chateaubriand not only lived through the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, he was an influential figure of national importance, and rose to become a Minister of State. His final statement on Napoleon (Memoirs, Book 24) shows how little he seems to have learnt from either books or experience (experiences which he thought about for years, and indeed wrote down in his memoirs in some detail).

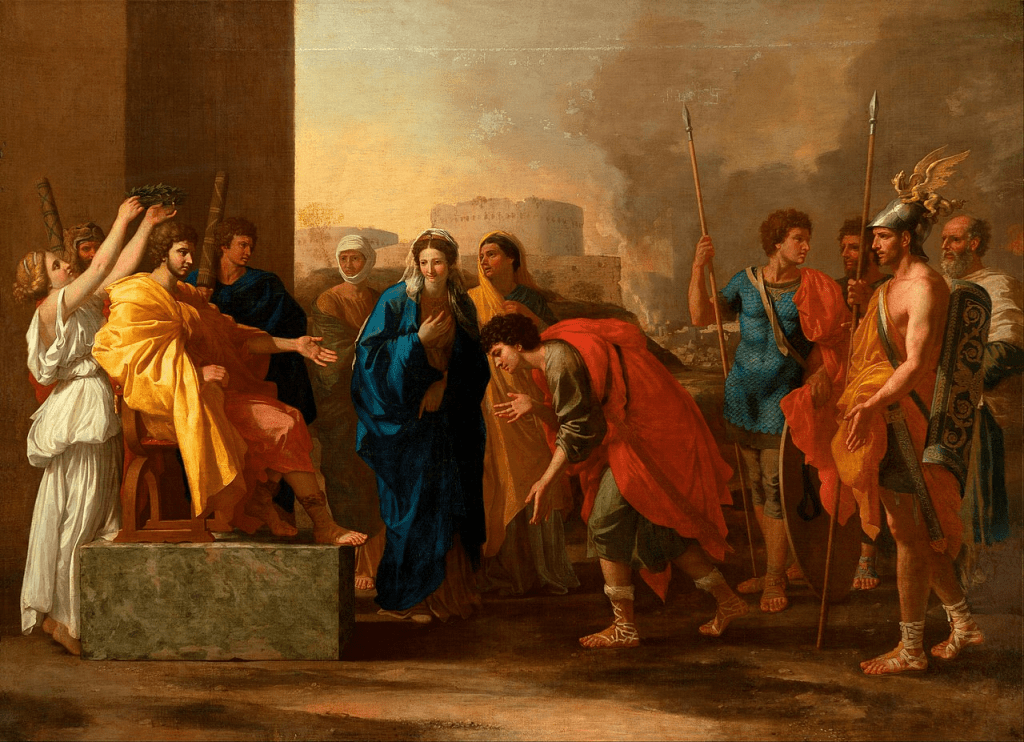

The rhetorical sweep of his comments has a certain grandeur: there are the predictable, obligatory references to Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, Thucydides, Demosthenes, Tacitus and so on; but he could have come up with most of this at second hand, without ever meeting Napoleon, or serving under him, or leaving his service in disgust. He has forgotten all of his own brilliant observations and shrewd insights. Or was Chateaubriand merely carried away by his own style, and the (admittedly Siren-like, entrancingly lovely) sound of his own voice? Was he trapped by the peculiarities of his style, so that he could not find a way of expressing what he knew without ‘breaking character’, or disrupting the unity of his work?

A major problem with literary ‘classicism’ may be that we do not really have obvious Greek or Latin models that show us how to express certain kinds of complexity or complication; the question of whether they are worth expressing at all is in fact a crucial one, at the deepest, most fundamental level. How useful is it to compare Napoleon to the great generals of antiquity, except as a shorthand manner of speaking? Chateaubriand appears, in Book 24 at least, to have trapped himself in the particular traditions in which he chose to write.

Of course, we do not read Chateaubriand for historical or political analysis; we read him because he was a captivating storyteller who accidentally shed light on pivotal events in history without realising it when he was more concerned with talking about himself and his emotions.

His old Latin master at the Collège de Dol was right to give him the nickname “The Elegist”: Chateaubriand has many of the faults, weaknesses and shortcomings of Ovid, Tibullus and Propertius, whilst also sharing their charms, qualities and very real virtues. Yet not everyone will be convinced of an elegist’s greatness: Tibullus too does not necessarily thrive in translation. Nor is his work an obvious inspiration or foundation for anyone who wants to write history, unless you are a historian mainly of yourself.

Tibullus, the author of a panegyric in dactylic hexameters to Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 BC–AD 12), who allegedly once said “I am ashamed of my power”, might not provide the ideal literary model for someone writing about Napoleon.

Part III of this essay series can be read here.

Jaspreet Singh Boparai recently abandoned academia to cultivate the Muses. He has previously written for Antigone on Tacitus and the thrill of writing here, on the challenges of translating (pseudo-)Latin here, on the pleasures of Poussin here, on Neo-Latin syphilis here, on Apuleius the ‘witch’ here, on V.S. Naipaul and Latin here, and on the Classics and British India here.

Further Reading:

The Penguin Classics edition of Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe (translated and edited by Robert Baldick as Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb, 1961; reissued 2014) has its merits, but the Alex Andriesse version (Memoirs from Beyond the Grave), of which two volumes have so far appeared from New York Review Books Classics (2018, 2022), is unabridged. If you decline to read this in French, you might as well read the first two instalments whilst waiting patiently for Andriesse to finish the job.

Other than the Memoirs, Chateaubriand does not translate well into English, as was noted above. But if you are willing to try him in French, see whether you enjoy his Vie de Rancé. His accounts of his travels in America (1827) and his journey to Jerusalem (1811) are superb; his fiction is perhaps an acquired taste for those of us who are not ‘Romantic’ in spirit.

The one major work of Chateaubriand’s to avoid even for most ‘Romantics’ is his Génie du Christianisme (1802), which was recently republished by Éditions Robert Laffont (Paris, 2022). The text is of great interest from the point of view of intellectual history; but Chateaubriand’s heart was not really in the subject, and the project served for him as a sort of postgraduate dissertation, to fill his mind with material that could later be transformed into art.

Christians will find the Génie particularly disappointing, except perhaps as an introduction or bluffer’s guide to the riches of the Catholic tradition, particularly with respect to elements that the institutional Church has been trying to suppress, or even crush, since the foolish ‘reforms’ of the 1970s. Even so, there are better guides.

An English translation of Chateaubriand’s study, issued under the title The Genius of Christianity, has recently been reprinted in America by Angelico Press (a small Catholic publisher with a very wide-ranging catalogue). Angelico has also published Martin Mosebach’s The Heresy of Formlessness (2018), which is short, elegant and far more enriching than Chateaubriand’s compendium.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Cited from the New York Review Books Classics edition (2018) of Chateaubriand’s Memoirs from Beyond the Grave 1768–1800, translated by Alex Andriesse. All excerpts from Chateaubriand will be taken from this version of the text, or its 2022 sequel (featuring Chateaubriand’s memoirs of the years 1800 to 1815). |

|---|