E.J. Kenney & Paul McKenna

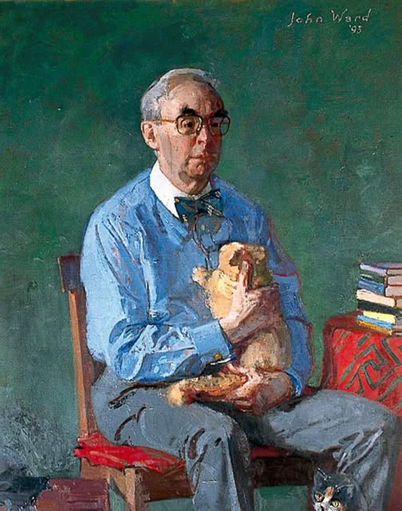

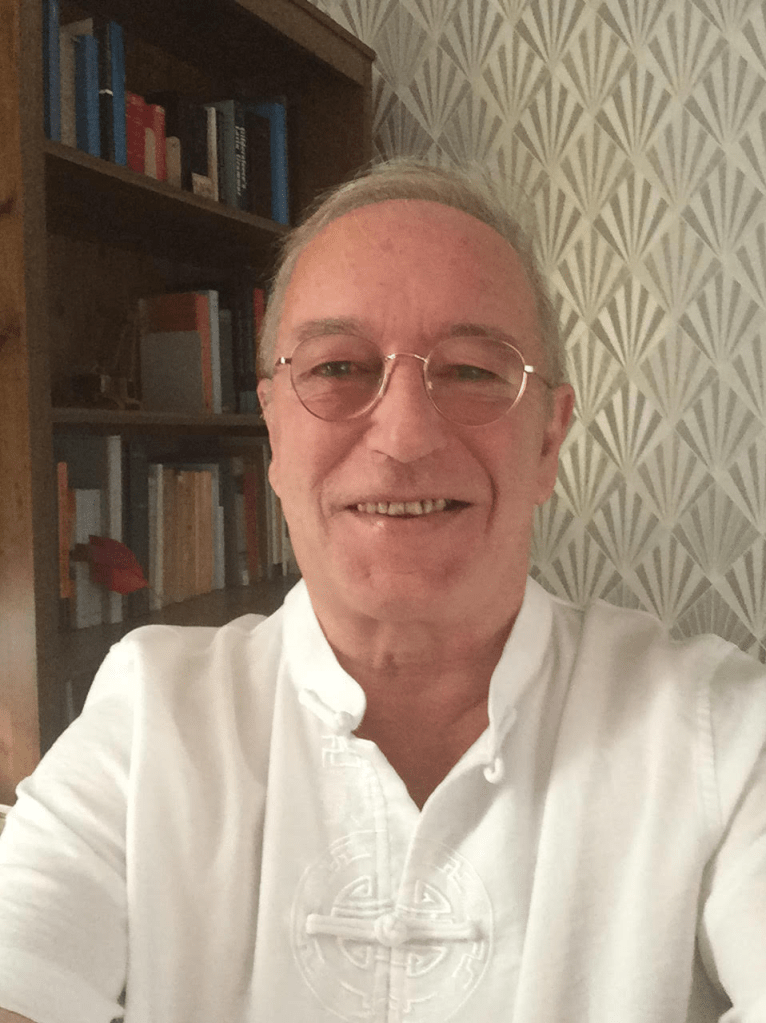

As the first in a new series, we are pleased to publish this short commentary on a piece of modern Latin verse. We welcome pitches for any poems, Latin or Greek, written after 1600 and which have no prior translation or commentary. Here is Paul McKenna’s translation and commentary on a poem written by the Cambridge Latinist E.J. Kenney (1924–2019) in 1979.

Text

ILLVSTRISSIMAE SOCIETATI STVDIIS GRAECIS DEDITAE

FRAGMENTVM NVPER REPERTVM

ET OVIDI FASTORVM LIBRIS DEPERDITIS FALSO ADSCRIPTVM

GRATVLABVNDA MITTIT SOCIETAS ROMANA

NOX erat, et fesso carpebam corpore somnos;

mens tamen a studiis inrequieta fuit.

atria mente vagans celsi per longa Palati

miror Apollineae scrinia docta domus;

dumque loci numen sancti reverenter adoro, 5

oranti adstiterunt numina bina mihi.

aut mihi sic visum est: geminas primum esse sorores

(credere enim facies hoc iubet ipsa) reor.

sed tamen, ut certe sit forma sororia in illis,

aetas non eadem est dissimilisque decor. 10

obstipui spectans: Graio fuit altera cultu;

enituit pulchro gratus in ore lepor.

altera erat natu minor, at robustius illi

corpus et in vultu paene virilis honos.

talibus inde ambae mihi sunt concorditer orsae 15

alloquiis, et vox una duabus erat:

‘O qui Romanae cultor studiosus inhaeres

doctrinae, monitus accipe corde meos.

ut non dividua est sapientia, sic ego partes

en individuas diva biformis ago. 20

nil refert Latione cites an nomine Graio:

adsum, seu Pallas siue Minerva vocor.

rite igitur populi, quos alma Britannia nutrit,

per duplices celebrant me, pia turba, choros.

maiori natu viden ut centesimus annus 25

advenit? huncne diem Musa tacebit iners?

tam faustus meritos habeat natalis honores

nec careant iusta debita sacra prece!’

finierat, sive illa fuit dea sive dearum

par germanarum, destituitque sopor. 30

iussum opus aggredior vixque haec temptamina promo

non satis expertae qualiacumque lyrae

indignusque fero ROMANI marcida COETVS

pro SOCIIS trepida serta poeta manu.

ergo nobilium comites salvete laborum, 35

rerum Graecarum quos merus urget amor.

iuncta salus nostra est: iunctis obeamus, amici,

viribus unanimae munera militiae.

sic constans fortuna beet, sic omne per aevum

clara micet GRAECI fama SODALICII. 40

Apparatus locorum similium (omnia sunt opera Ovidii nisi aliter indicantur)

1 Am. 3.5.1 | 2 Tr. 5.2.7 | 7 Her. 17.157, Met. 4.774 | 11 Virg. Aen. 2.10, 6.612, Met. 3.174f | 25 Cat. 62.8, Virg. Aen. 6.779, Tib. 2.1.25 | 29 Fasti 5.53. | 30 Rem. 576 | 40 Tr. 4.10.46

Translation

It is common for a translator of ancient literature to offer some sort of apology, or explanation at least, for the translation and, since I am nothing if not a traditionalist, here’s mine: my prose translation aspires to no poetic quality, I simply hope to provide a serviceable walking stick to support a less-confident reader through the Latin. Better scholars and poets of English can readily improve it until it becomes whatever they consider to be “better”.

OFFERING CONGRATULATIONS THE ROMAN SOCIETY SENDS TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS HELLENIC SOCIETY STUDIES A FRAGMENT RECENTLY DISCOVERED AND FALSELY ATTRIBUTED TO OVID’S LOST BOOKS OF THE FASTI

It was night, and with a weary body I was snatching sleep; yet my mind was restless from studies. Wandering in my mind through the lofty halls of the long Palatine, I marvel at the learned bookcases of Apollo’s house; and while I reverently adore the authority of the sacred place, (5) two goddesses stood by me as I prayed. Or so it seemed to me: I first thought that the sisters were twins (for their faces themselves bid me to believe this). But yet, as there may certainly be a sisterly form in them, their age is not the same and their beauty dissimilar. (10) I was dumbstruck as I watched: one was of a Greek culture; a pleasing charm shone on her beautiful face. The other was younger by birth, but her body was more robust and her expression had an almost manly dignity. Then both began to speak to me in unison, (15) and the two had one voice: ‘O you who are a diligent worshipper of Roman doctrine, accept my advice in your heart. As wisdom is not divided, so do I play the indivisible role as a goddess of two forms. (20) It matters not whether you call me by a Latin or by a Greek name: I am here, whether I am called Pallas or Minerva. Therefore, the people, whom the soul of Britain nourishes, pious crowd, celebrate me with double choirs. Do you see that the hundredth year from birth is approaching to the older one? (25) Will the Muse remain silent on this day? May such a happy birthday have the honours it deserves nor may they lack the just and sacred prayer due!’ She had ended, whether she was a goddess or equal to sister goddesses, and sleep abandoned me. (30) I set about the task which had been ordered, and scarcely do I begin these attempts, not sufficiently expert with whichever sort of lyre I carry, and I, an unworthy poet, bear feeble garlands of the ROMAN ASSEMBLY in trembling hand for my comrades. Therefore, hail, companions of noble labours, (35) whom pure love of Greek matter urges. Our prosperity is united: let us, friends, fulfil the duties of a united military force. Thus may constant fortune be blessed, thus may the fame of the GREEK SOCIETY shine brightly throughout all eternity. (40)

Commentary

Structure

1–4 a first-person internal narrator sets the scene.

6–27 the two goddesses

14–27 the two become one and speak in first person singular.

28–fin the narrator responds to this speech

31 a recusatio?

33 … immediately followed by cautious agreement.

34 the narrator finally identifies the narratee who is (are) the congregated scholars of the two societies.

39–40 the climax in which the narrator expresses a wish that constant fortune be blessed and that everlasting fame should shine forever.

Narratology

Who is the narrator? Male or female? There is neither adjective nor participle which defines gender. A real person or a literary construct? The truth is that there is nothing internal to the poem which gives us a definitive clue.

Where is the poem set? Can we say any more than ‘in a bedroom, going to bed’? I doubt it, until the mention of addressees in v.35 and v.37 when it seems that all of the internal characters are at a meeting.

When is the narrator speaking? The first three main verbs (erat and carpebam v.1 and fuit v.2) immediately set the scene in the past; miror and adoro should be considered historic present tense. The central character-speech is obviously present tense and only tells us that they are at the time of a 100th birthday. Once more, it is not until the conclusion that we readers are able to confirm that the subsequent events are in the narrator’s present.

There is nothing in the poem which assures us that the poet is the narrator (in fact only an incautious critic would claim that the narrator is the poet). History and para-literary notes tell us that it is 1979 and Prof. Kenney has composed the piece to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Hellenic Society. It was read by the then President of the Roman Society, Prof. A.L.F. Rivet, at the Centenary Reception on Wednesday July 4th, which was held at the Fishmongers Hall, London Bridge. The text was printed in JRS 69 (1979) xi. All of this information was gleaned from the archives of the Journal of Hellenic Studies and especially Volume 100 Centenary issue 1980.

Notes

Metre

Ovidian elegiac couplets

Title … SOCIETATI STVDIIS GRAECIS DEDITAE… a close paraphrasis for Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies || Note Prof. Kenney’s humour in “recently discovered and falsely attributed to…”.

1 Nox erat See Amores 3.5.1 || somnos for the plural see Kenney, Ovid: Heroides XVI-XXI (1996) and his note on Her. 20.132: “somnus is used indifferently in sing. and pl. (OLD s.v. 1a)”. Of course, according to the metre, somnum would have been fine.

3–4 atria… Palati, Apollineae… domus These specific locations need not be taken literally: they are given as examples of synecdoche, pars pro toto, much as we would now say in English ‘the corridors of learning’. Note that the former is expressly Roman and the latter Greek, a dichotomy which will become a leitmotif

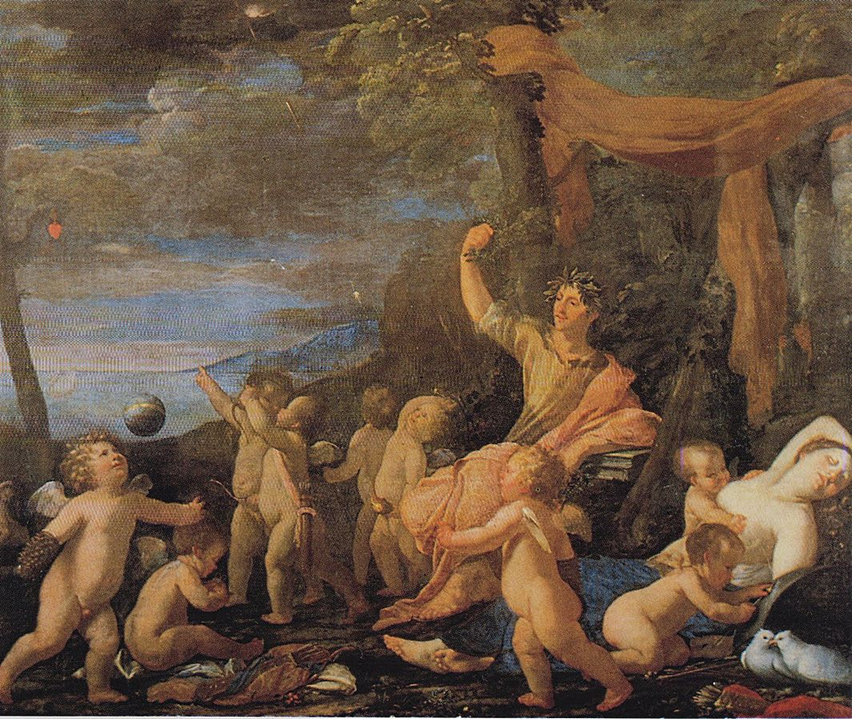

6 numina bina Prodicus provides the source for this not uncommon poetic conceit as recorded by Xenophon’s Memorabilia 2.1.21–34. Two women (goddesses) with opposing world views appear to a male character who then must decide which (metaphorical) path to follow.

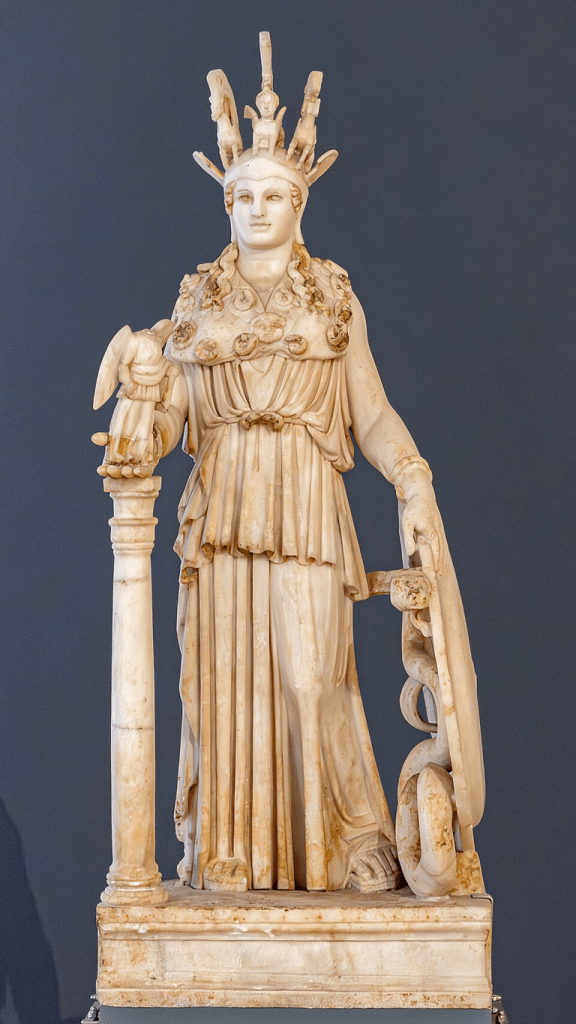

11 obstipui ‘I became dumbstruck’, see Virg. Aen. 2.10, 6.612 and Met. 3.174f. || altera One goddess was Greek whose “pleasing charm shone in her beautiful mouth”, we can extend this observation through metaphor to mean she has ‘a beautiful language’ and then further to she has ‘beautiful literature’. || altera The younger goddess possesses the quality of ‘virility’ so the etymological link is to ‘virtue’, i.e. she is Roman.

18 monitūs Accusative plural, assured by metre, in agreement with meos.

19 sic ego partes Two disyllabic words at the end of a hexameter should ideally be preceded by a monosyllable which itself follows a pause. The syntactic sense unit should also carry on in enjambment some way into the pentameter. See Winbolt Latin Hexameter Verse (1903) §102, 137ff.

22 Pallas sive Minerva once again the Greek/Roman dichotomy is highlighted.

25 viden A contraction, common in comedy, of vidēs + ne that is rare in dactylic poetry but see Cat. 62.8, Virg. Aen. 6.779, and Tib. 2.1.25, where it is also always followed by ut.

26 advĕnit Metre confirms that the verb is in the present tense.

29 finierat A word often used by Ovid at the end of oratio recta, or direct speech, for example Fasti 5.53, among others.

30 destituitque sopor Destituo is a transitive verb so we must understand me (me).

31ff. This is effectively a narrator’s recusatio but it is not in the pure form employed by Augustan poets. The narrator does not claim to be insufficiently skilled or unwilling for the task in hand, merely that it will be a struggle. Unlike in the Augustan recusatio, where the request is only implied by the narrator’s refusal, here we actually have it. The topos of recusatio can be traced back to Callimachus Aetia 1.21–4. Virgil, Horace, and especially the elegists made full use of the idea.

32 qualiacumque lyrae Is the narrator considering writing lyrics in the style of Horace? Mention of lyra would certainly make a reader think so.

33 COETUS Scanned as a disyllable, as always in Ovid.

38 militiae Quite rarely does Ovid close a pentameter with a four-syllable word and when he does it is often a proper name, see Platnauer Latin Elegiac Verse (1951) 7. Propertius uses this word twice at this position, 1.7.2 and 1.21.4.

40 SODALICII Five-syllable words at pentameter ends are also avoided (only 12 instances in Ovid’s oeuvre, Platnauer loc. cit.). I translate sodalicii as ‘Society’ which its capitalisation with GRAECI suggests. However as the final word in the piece I cannot help but to think that in this context its wider meaning of ‘fellowship’, ‘brotherhood’, ‘companionship’ being thrown into an emphatic place should not be dismissed. See Tr. 4.10.46, or the closing line of A.E. Housman’s elegiacs to Moses Jackson in his edition of Manilius I (1903): et non aeterni vincla sodalicii.

Although Prof. Kenney’s message is sincere in form and content he imbues it with his scholarship, characteristic lightness of touch, and humour, I trust that anyone who has read this far will see that I too am having a little fun, at our own expense.

Now drifting slowly into retirement from the oil and gas industry, Paul McKenna is delighted to consider himself an independent scholar thinking and writing about Classical literature again. Although Greek epic from Late Antiquity is his most comfortable place, studying Horace and the three Roman elegists alongside their modern emulators is a current joy. His earlier essays on the O Tempora Latin crossword puzzles in The Times and Claudian’s Greek Gigantomachia can be read here and here.