Edmund Stewart

What is the purpose of human life? For the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC), human beings as a whole have a particular function, by which we can find fulfillment and happiness. Those of us who do not, or cannot, fulfil that function will find that we are incapable of achieving our potential as human beings. What, then, should we be doing?

Aristotle’s thought on these questions is most famously laid out in the Nicomachean Ethics (a treatise named after Aristotle’s son Nicomachus, who appears to have edited his father’s writings). In this work, we are told that the ultimate end of human life is Happiness (εὐδαιμονία, eudaimoniā).

τοιοῦτον δ᾿ ἡ εὐδαιμονία μάλιστ᾿ εἶναι δοκεῖ· ταύτην γὰρ αἱρούμεθα ἀεὶ δι᾿ αὐτὴν καὶ οὐδέποτε δι᾿ ἄλλο, τιμὴν δὲ καὶ ἡδονὴν καὶ νοῦν καὶ πᾶσαν ἀρετὴν αἱρούμεθα μὲν καὶ δι᾿ αὐτά (μηθενὸς γὰρ ἀποβαίνοντος ἑλοίμεθ᾿ ἂν ἕκαστον αὐτῶν), αἱρούμεθα δὲ καὶ τῆς εὐδαιμονίας χάριν, διὰ τούτων ὑπολαμβάνοντες εὐδαιμονήσειν· τὴν δ᾿ εὐδαιμονίαν οὐδεὶς αἱρεῖται τούτων χάριν, οὐδ᾿ ὅλως δι᾿ ἄλλο. (1.1097 b.1–7)

Happiness above all else appears to be absolutely final in this sense, since we always choose it for its own sake and never as a means to something else; whereas honour, pleasure, intelligence, and excellence in its various forms, we choose indeed for their own sakes (since we should be glad to have each of them although no extraneous advantage resulted from it), but we also choose them for the sake of happiness, in the belief that they will be a means to our securing it. But no one chooses happiness for the sake of honour, pleasure, etc., nor as a means to anything whatever other than itself. (trans. H. Rackham)

What does this all mean? Aristotle is dealing with the problem that in our lives we are constantly facing different goals and trials and no one person carries out the same tasks. Specialisation was most evident to Aristotle (as it was to his predecessors Plato and Socrates) in the field of work. Doctors and carpenters and musicians all have different aims (health, a house or good music) and all appear to gain some fulfilment from this. But what is the ultimate purpose of all this activity?

Aristotle’s answer is that Happiness is the only thing that is done entirely for its own sake. What is most surprising is that even exceptionally high things, such as virtue, are done not only for themselves but also for the sake of Happiness. The Greek word for virtue is ἀρετή (aretē), translated in the passage above as ‘excellence’. The notion of excellence includes simply being good at something (there is an excellence in being a good doctor, for example), but also goodness and the other virtues themselves (Justice, Temperance, Prudence, etc.).

It may appear strange that an ancient philosopher should view excellence as in some way subordinate to Happiness. Are we not meant to be good, rather than necessarily happy? Is Happiness not in some sense an incidental reward for a good life? Well, Aristotle regards both Happiness and Virtue as a kind of activity. We are happy and good while we exercise as happy and good people. Moreover, Happiness is activity that is in accordance with Virtue. We must practise being a good person, and doing good, and in the process we are happy.

Every human art and endeavour aims at good of some kind, to paraphrase the opening line of the Nicomachean Ethics.[1] However there is a clear hierarchy of good things. A doctor can be an excellent doctor, which is an achievement that will bring fulfillment in the exercise of that excellence, but such goodness is fundamentally limited. We need also to be excellent people, that is to practise excellence not just in art or science (τέχνη, technē), but in the overall excellence of being a human being. Health is the product or function (ἔργον, ergon) of a doctor. But we do not want to be healthy for the sake of health; we want to be healthy so that we can live. What should we be doing while we live?

Human beings share with plants and animals the basic function of living and growing. But we are unique in being capable of ‘a certain activity belonging to that faculty that possesses Reason’ (πρακτική τις τοῦ λόγον ἔχοντος, 1.1098a.4). The greatest excellence is in Reason, so the greatest happiness is to be found in Contemplation, the practice of Reason. It is principally through the life of Contemplation that we can fully achieve the life we should lead as human beings and so be happy. As teachers and students at schools and universities, this is in fact our one job.

So let’s recap: what is Aristotle telling us about how to live?

-

- Our ultimate purpose in life is to be happy;

- But that happiness is not to be found in wealth, health, pleasure, success, fame, or even virtue, since all these things, while good in themselves, are only aids to life, not its purpose;

- Happiness is the practice of living as a rational being in accordance with what is good – we practise goodness in order to be happy;

- Happiness is not tailored to individuals: we do not find happiness by suiting the world to ourselves, or in living ‘our best life’, but in finding and fulfilling the function for which we exist on Earth;

- As such, life lived in accordance with vice and meanness, or even in the practice of petty and banal tasks, cannot lead to happiness – there is activity that makes us better and activity that makes us worse;

- There is also activity that, while good, supplants happiness as the goal of our life if we want it to, so that health or wealth or fame can perversely come to be the whole purpose of life.

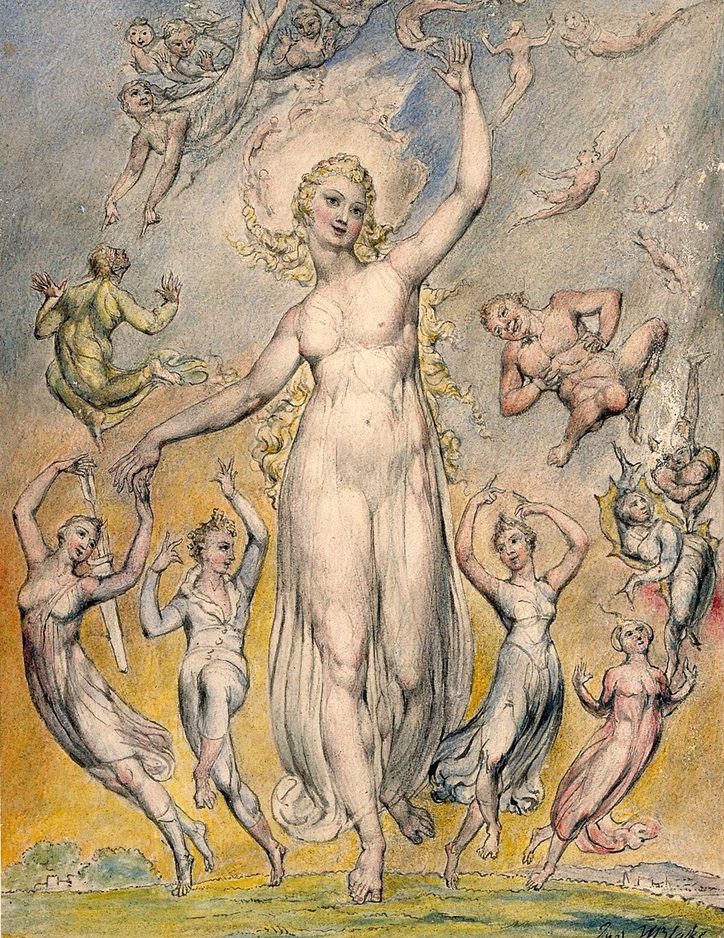

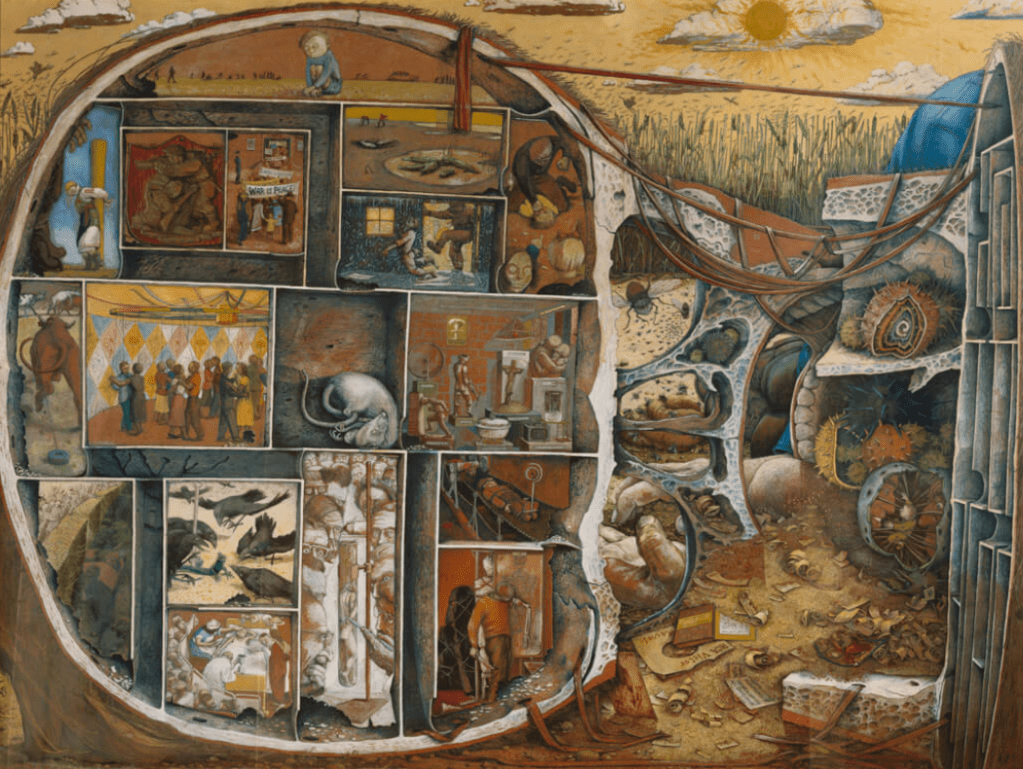

To understand what Aristotle means, I strongly recommend watching the 2024 Disney Pixar movie Inside Out 2. For those of you who have not seen the film, briefly the plot concerns the life of a young girl called Riley, who is just embarking on her teenage years and starting to go through puberty. The central action of the film, however, is set inside her head. Pixar presents a wonderfully imaginative and amusing allegory of what goes on inside our minds. In this world, all the metaphors we use for thought are brought to life with wonderful literalness: a train of thought actually is a train; the stream of consciousness actually is a river, etc., etc. At the front of the brain is the headquarters, a tall tower opening on the eyes (not unlike a Platonic ‘acropolis’ of the soul), which is governed by the emotions.

The leader of the emotions, in the child Riley, is Joy: she makes Riley happy by governing her reason. But as puberty kicks off, new emotions emerge. A band of newcomers, led by Anxiety, launch a coup, capture the headquarters and drive Joy and her followers into exile in (quite literally) the ‘back of the mind’.

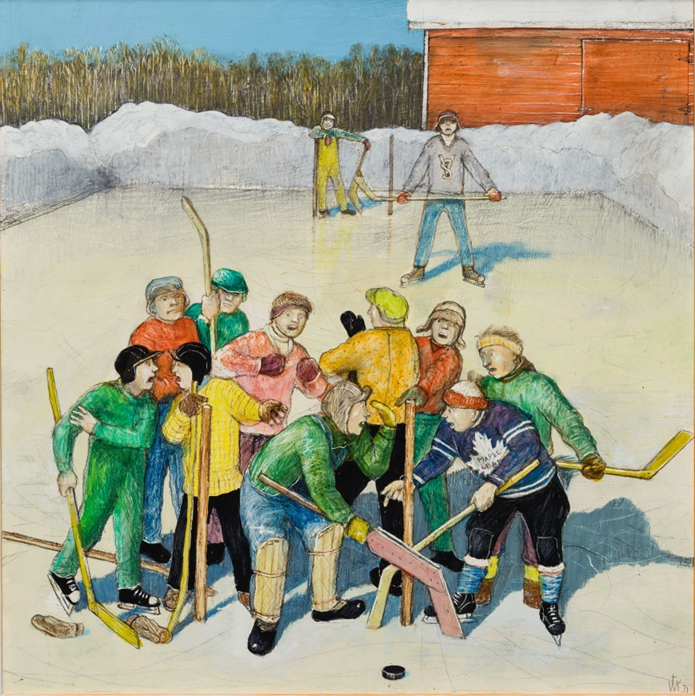

Anxiety wants Riley to be good, excellent in fact. In this way, she claims to be acting in Riley’s best interests. Riley loves ice hockey, so Anxiety will make her exceptionally good at ice hockey. At the same time, she wants Riley to have friends who are best placed to help her succeed and be popular at school. In Aristotelian terms, Happiness, or Joy, has been subordinated to the quest for Excellence (aretē). Her friendships are to be made not for pleasure in another (which is how Aristotle believes children generally make friends), but (as adults do) for expediency: these are the right people to help her get on.

But what is this all for? Anxiety has forgotten and is also forcing Riley to forget who she is. In Joy’s absence, Riley breaks with her old friends, does things she knows to be wrong and finally drives herself into a panic attack through a desperate bid to gain her coach’s approval. In one of the most moving moments of the film, Joy, when faced with the chaos Anxiety has unleashed, asks herself sadly whether this is just what growing up has to be: when you grow up you feel less joy.

But it does not have to be like this. Joy can reclaim the citadel of our consciousness, whatever your age.

There are, nevertheless, clearly two traps we need to avoid. The first is, while doing good, to make achievement and success your whole end in life. If you do that you will wake up middle-aged one day and find that you are not in fact doing what you first enjoyed doing and what you first set out to do in your youth. You are no longer playing games, or reading books, or making music; you are sitting in committees governing the practice of sport, or education, or music, made up of people who manage the other people who still play or read or sing. After that, it will steadily become clear that what really matters is not in fact the work at all, but the institution or policies or processes that ‘promote’ the work.

The second trap is to do no good at all. We can lose ourselves in a morass of pointless, banal and mean tasks that achieve nothing worthwhile, or not enough, at any rate, to sustain our souls or intellects. If so, your only pleasure will come from bullying those who still play or work with threats of policies and forms and regulations. You and your fellow administrators hate your work, but at least (you tell yourself) you are one of the grown ups, doing work that (for some always unexamined reason) needs to be done.

Or you may indeed, at worst, turn entirely vicious. If so, you will find that your only comfort comes from a certain fellowship in vice. Your friends are people who, like you, pursue what makes them miserable, and who encourage others to do the same. They are left with one sole perverse pleasure, which stems from knowing that at least they are numbered among the special ones, too clever to conform themselves to ‘traditional morality’, who prefer to live in defiance of Happiness and everyone who is happy.

If you are a student starting the new academic year, I pray that you will make Joy your calling, both now and in your life to come. Work at something good. You will know a good thing when it gives you pleasure and a sense of fulfilment that is entirely disinterested. Learn to be a good craftsman, not a successful one. And make friends with people because you recognise there is something good in them and because you love them for it.

If you are a teacher, in whatever setting, think about how you can impart Joy to your students. You became a teacher because you felt Joy as a student. Ask yourself if you are really teaching what is good, or merely things that promise or pretend to lead to good. Are you urging your students on towards the practice of Goodness and Virtue? Or are you just telling them that they are good as they are (and hoping it to be true)? Are you helping your pupils to understand Beauty and to make or do things that are beautiful? Or do your lessons focus merely on what is mechanical or mundane? Are you moulding human beings? Or are you training employees?

Above all, ask yourself all the time if what you are being asked to do is going to lead to some real good, for you, your pupils and the world. If it is not, maybe stop doing it. Remember always your purpose and duty to your students, which is to make them better. This is what is important, not what Management says is important.

The start of the 2025/26 academic year began with the assasination of the activist Charlie Kirk on a college campus, at Utah Valley University. The accused shooter is a 22-year-old drop-out from Utah State University who was then enrolled at a local technical college. What can be going on in the head of a young person who sets out to commit a pointless murder that will achieve no good for anyone, least of all himself and his family, and cause so much woe and suffering to those who loved the victim? We cannot know for certain, but it is a fair guess that it has something to do with the loss of Happiness as a central goal in this young man’s soul.

Misery at its most profound prompts more misery and no longer seeks to reclaim the Joy that has been lost. This is to hate Good because we are evil; to hate Happiness because we are unhappy. As teachers, let us consider deeply whether what we teach really serves the end of Happiness. It may prove a matter of life and death, of Heaven or Hell.

Edmund Stewart is Assistant Professor in Ancient Greek History at the University of Nottingham. He has previously written for Antigone on how to build a Greek temple, and his various other essays can be found via our writers page.

Notes

| ⇧1 | πᾶσα τέχνη καὶ πᾶσα μέθοδος, ὁμοίως δὲ πρᾶξίς τε καὶ προαίρεσις, ἀγαθοῦ τινὸς ἐφίεσθαι δοκεῖ·, 1.1094a.1. |

|---|