An Antigone Explainer

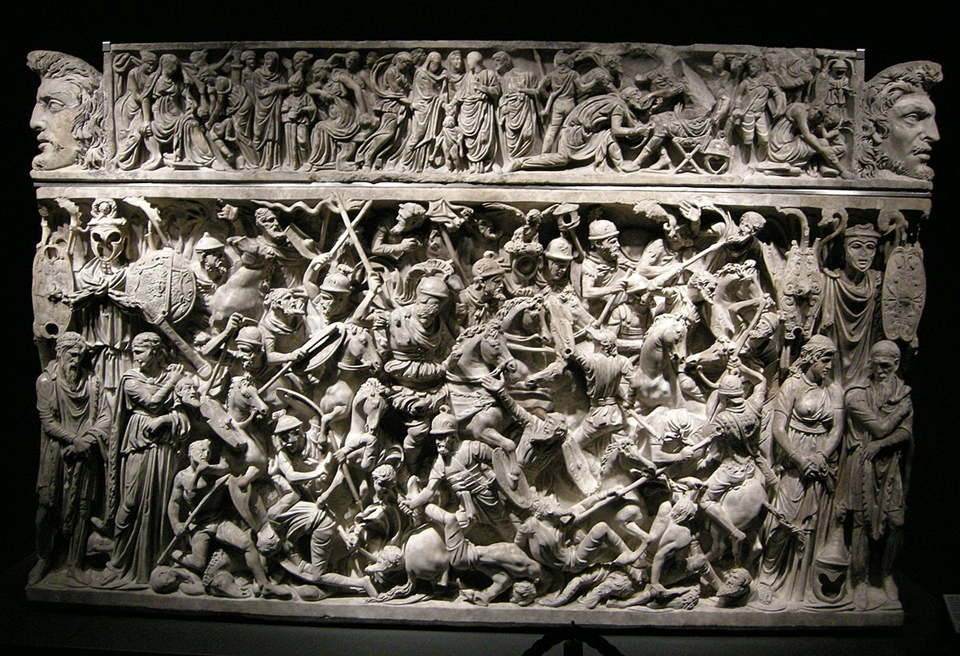

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome is one of the greatest of all ancient artworks. Yet it presents us with a certain number of riddles; we will not try to solve those here. For the moment we might simply enjoy looking at the sarcophagus before we even think about contemplating its enigmas, or shedding light on them. There is no point in studying something you do not love – unless it helps you understand something that you do, of course.

Victories against Barbarians

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus is named after the district in Rome where it was discovered in 1931. It is one of two dozen or so extant ‘battle sarcophagi’ that were produced in the Roman Empire, mainly between AD 170 and 210, and feature scenes of Roman victory over barbarians. The latest of these battle sarcophagi, the so-called Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus, appears to have been produced in the 250s, during the Crisis of the 3rd Century. Its technical qualities are all the more impressive when you consider how far Roman art was in decline at this point in history.

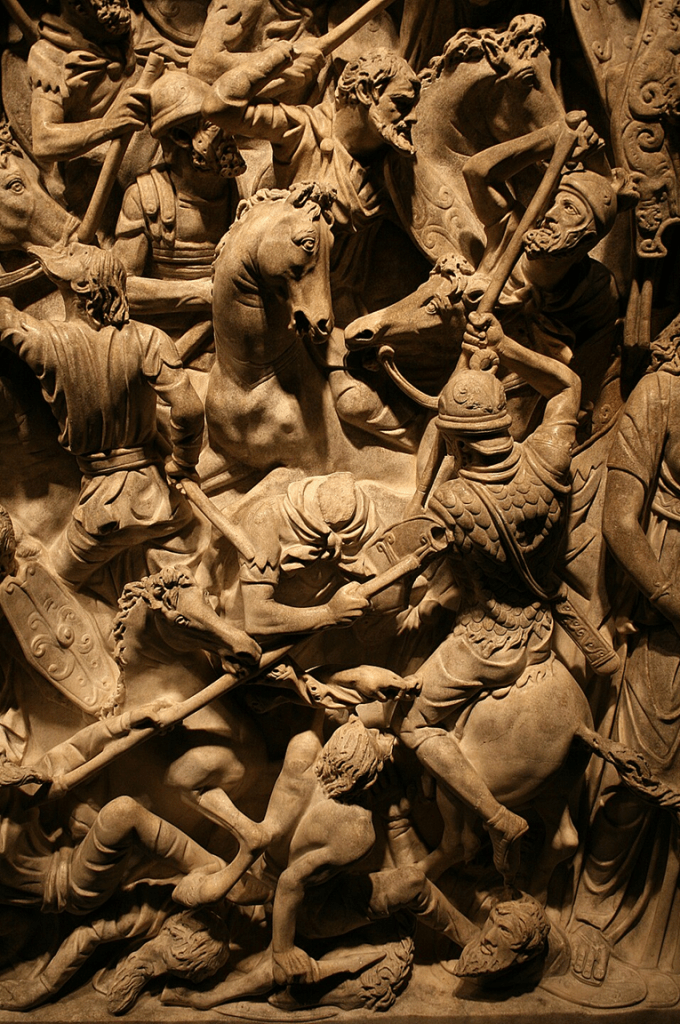

Battle sarcophagi ultimately derive their imagery from Hellenistic precedents – for example, monumental sculptures in Pergamon commemorating victories against the Gauls – but we shouldn’t presume that artisans of the 2nd century AD had direct access to such memorials. Their main influences were inevitably local. The Roman workshops where some of the very finest battle sarcophagi were created seem to have drawn inspiration from Trajan’s Column, the Column of Marcus Aurelius, and the now-vanished Arch of Marcus Aurelius.

Trajan’s Column was completed in AD 113, and still stands in Trajan’s Forum in Rome. This impressive monument commemorates the Emperor Trajan’s victories in the Dacian Wars (101–2 and 105–6). Few who are not art historians or artists pay close attention to the imagery, which is difficult to take in unless you spend a few hours systematically photographing it – or better, making detailed drawings of it from all sides.

Trajan’s Column stands 115 feet high; the Column of Marcus Aurelius is even taller, at 130 feet. It seems much livelier and more sophisticated than its predecessor; the artists and artisans who worked on it appear to have had more fun with their material.

The Column of Marcus Aurelius commemorates the Emperor’s victory in the Marcomannic Wars, which began in AD 166. On 23December 176, Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus celebrated a joint triumph in honour of their glorious victory over the Germans and Sarmatians, only to see hostilities resume a few months later. Military operations against these barbarians carried on even after Marcus Aurelius died in 180, although by 182 Commodus seemed confident enough about the permanence of his victory to adopt the title ‘Germanicus Maximus’.

The dedicatory inscription for the Column of Marcus Aurelius is long gone, but the monument seems to have been competed by 193. We can only speculate on the precise mechanisms whereby it influenced Roman sculptors and artisans of the period. All we know is that there are clear connections between the sculptures on the column and the style, composition and general approach of the Column of Marcus Aurelius, to say nothing of the remaining reliefs from the (now-dismantled) Arch of Marcus Aurelius, which seems to have been completed in time for the emperor’s triumph in December 176. But the reliefs from the arch don’t feature battle scenes or dynamic action, of course.

In Honour of the Faceless

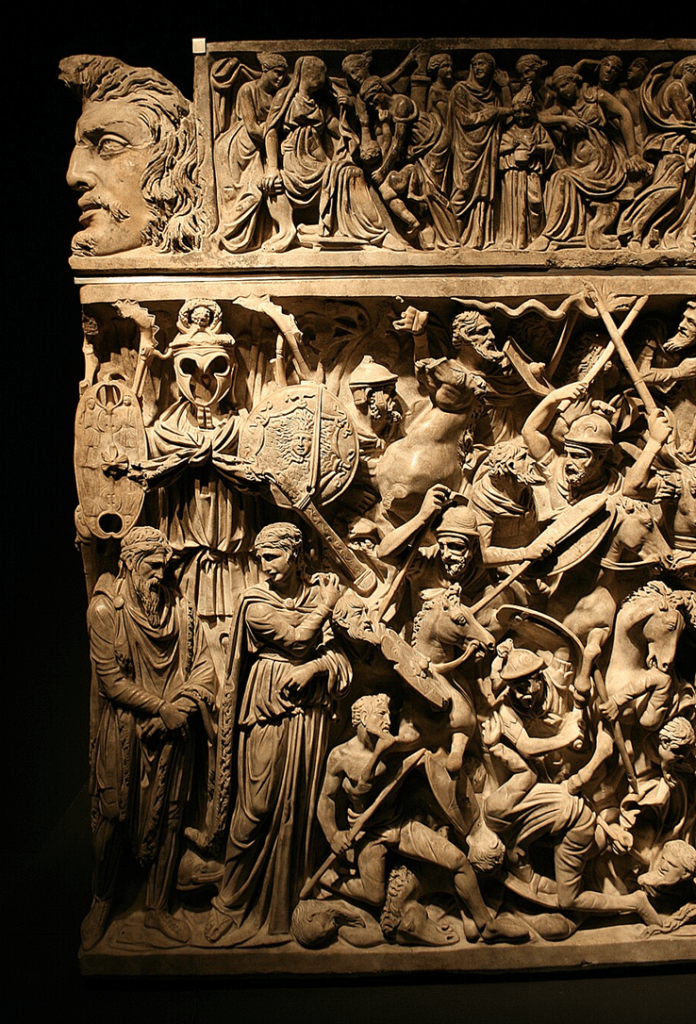

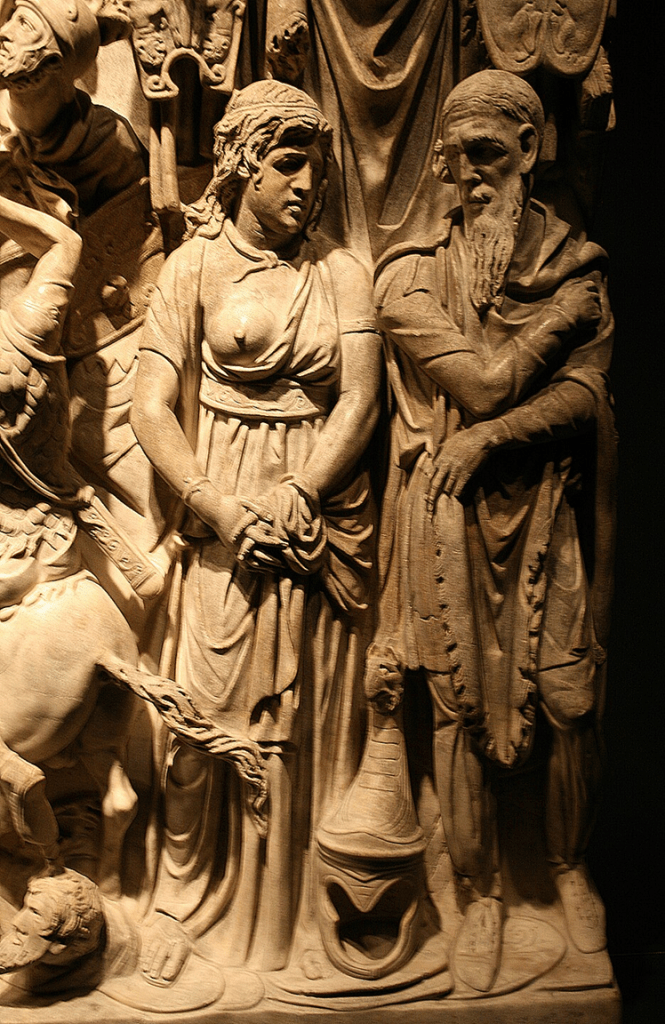

Some scholars think that the Portonaccio Sarcophagus was created for Aulus Julius Pompilius Titus Vivius Laevillus Piso Berenicianus (c.140–80), who was elected consul in 180. But the sculptures are unfinished: all the most important figures lack faces, which makes one wonder whether this was a commissioned piece, or was simply produced ‘on spec’ as a sort of generic luxury item for the families of aristocrats who won fame fighting against barbarians. The central figure on the sarcophagus, a general on horseback, has a rough marble oval where a portrait of his face ought to be.

You can be forgiven for finding all the detail overwhelming. It takes some time to get a sense of what is going on here. The lid of the sarcophagus features masks of barbarians at each end.

On the left side of the lid, a faceless mother seems to watch her infant being bathed; the next image seems to be an education scene (?) with a young girl between two women, unless we are misreading this radically.

At the centre of the lid there is a dextrarum junctio (joining of hands), a betrothal scene, then the entire right half seems to be taken up with elaborate submission rituals on the part of defeated barbarians.

As for the body of the sarcophagus: the image is a little less confusing if you divide it into four levels, or registers, from top to bottom, with two layers of Roman cavalry at the top, a layer of infantry below them, and – at the bottom, of course – defeated, subjugated barbarians.

At left and right there are trophies of barbarian arms and armour, and a pair of humiliated captives (female as well as male) who are recognisably non-Roman in their hair and clothing.

All of this is tied together by the faceless general, who is presumably the son of the faceless mother from the lid. He should have unravelled all of the mysteries; instead he complicates them even further.

A Moment Saluting the Past

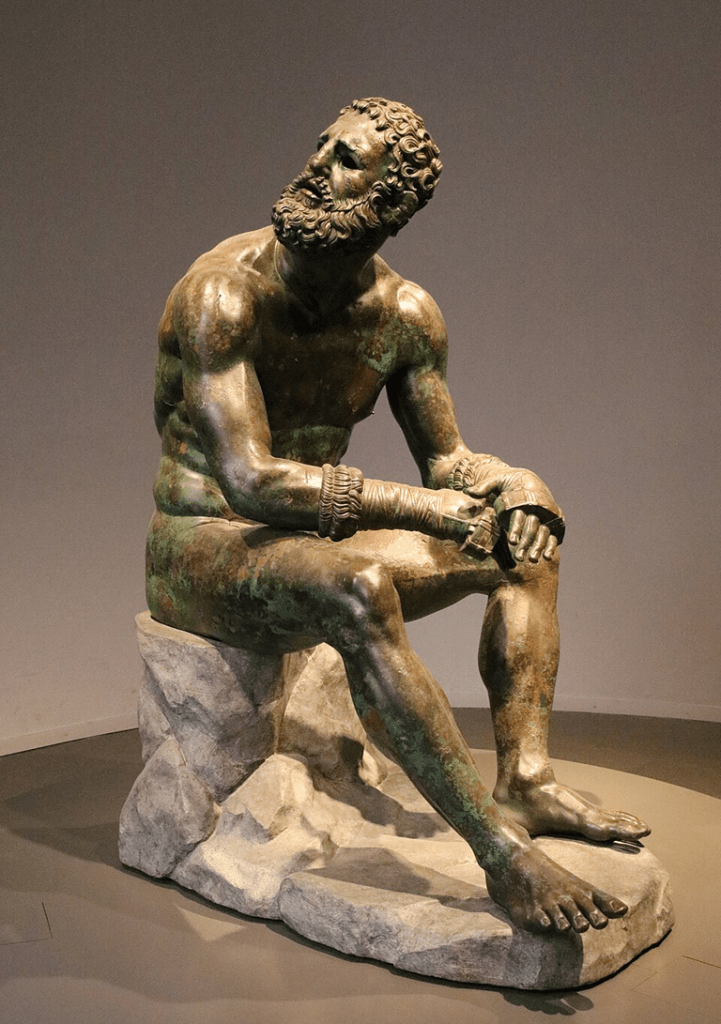

The Portonaccio Sarcophagus captures a final moment of triumph before Rome began her long decline into chaos and decay. This gives it a certain poignancy that we do not find even in the most moving of the other ancient masterpieces in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme – Livia’s Garden Room, the Boxer, and the beautiful marble statue from Tivoli of the crouching Venus (originally by the otherwise-unknown Hellenistic sculptor Doidalses).

Perhaps the Portonaccio Sacrophagus is a tomb, not for some victorious general, but for pagan Rome itself. Nothing as great as this would be produced again in the West for many centuries.