Edmund Racher

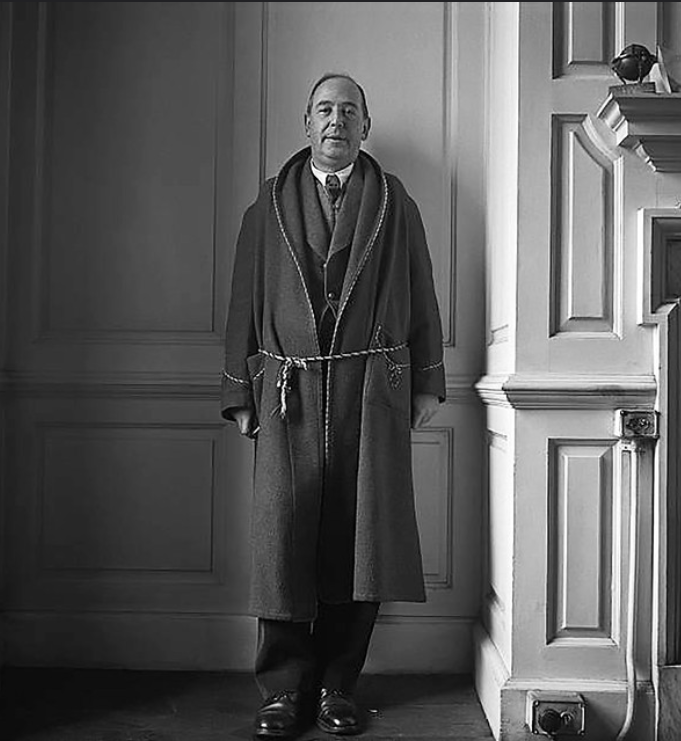

Even those familiar with the works of C.S. Lewis may be taken aback to see him referred to as an author of historical fiction. Far more familiar are his apologetics, his Cosmic or Ransom Trilogy and (undeniably) the Chronicles of Narnia. However, he was an author of one work of historical fiction, Till We Have Faces (1956). A fragment also exists of After Ten Years, a novel planned around Menelaus and his relationship with Helen in the aftermath of the Trojan War. On top of this, we have frequent discussion in his letters about historical fiction; also through his academic writing – notably The Discarded Image and the Oxford History of English Literature in the Sixteenth Century – he spent a good deal of time surveying, considering and writing on the past. All this makes Lewis interesting to compare with his contemporary Naomi Mitchison, an author of historical fiction who began publishing novels before he did.

Naomi Mitchison was born in Edinburgh in 1897 as Naomi Haldane.[1] She was educated at the Dragon School and St Anne’s College, Oxford. After service as a nurse in the First World War, she began writing. Her first novel was The Conquered, published in 1923, which deals with Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. Later historical fictions include Cloud-Cuckoo Land (1925), the story collection Black Sparta (1928), and The Bull Calves (1947). She married the barrister and Labour politician G.R. ‘Dick’ Mitchison in 1916, became a member of the Fabian Society, and stood as a candidate for the Labour Party in Parliamentary elections. She died in 1999.

Lewis and Mitchison were both born in the Celtic fringe of Britain (Ulster and Scotland) at roughly the same time (1898 and 1897). Both had homes in Oxford (granted, Lewis for much longer). Both served in some capacity in the First World War. Both became public intellectuals, albeit Mitchison rather earlier, writing and campaigning in the 1930s, while Lewis gained prominence during the Second World War, with The Screwtape Letters (1942) and the radio talks (1941–4) that would become Mere Christianity (1952). But the comparison that seems most interesting involves two of their novels: the aforementioned Till We Have Faces and Mitchison’s 1931 novel The Corn King and the Spring Queen.[2]

The Corn King and the Spring Queen is perhaps Mitchison’s largest work; her obituary in the Independent by her near-contemporary Elizabeth Longford says that “It is generally agreed that her finest novel, and perhaps the best historical novel of the 20th century, is The Corn King and the Spring Queen.” It has been republished more often than her other works of fiction – with relatively recent paperback editions by Virago (1983), Canongate Classics (1990, 2010) and the Soho Press (1994).

Events begin in the land of Marob, from the point of view of a young woman named Erif Der. She is brought into marriage with Tarrik, the young Corn King – thus becoming Spring Queen. However, when Tarrik rescues from shipwreck the Greek philosopher Sphaeros (Sphaerus of Borysthenes, c.285–210 BC) there begins an exchange with Greece, not just of goods, but of ideas as well. Both Erif Der and Tarrik eventually travel to Greece – notably the Sparta of Kleomenes III (Cleomenes III, lived c.280–219 BC, reigned 235–222 BC).[3]

Sparta is initially shown from the point of view of the young Spartiate Philylla, who will become entangled with Erif’s brother Berris Der, a craftsman and artist. Tarrik and Erif Der will come of age amidst the entangled myth-culture and politics of Marob, and find themselves compelled to navigate the alien customs of Sparta and the other Greek states – not least their wars and internal feuds, though they do find some surprising similarities with Marob. Erif and Tarrik will eventually follow Kleomenes into exile in Ptolemaic Egypt, where they both encounter the intrigues at the court of Ptolemy IV (244–204 BC), as well as the distantly familiar cult of Isis and Osiris.[4]

The 1990 Canongate Classics paperback edition of The Corn King and the Spring Queen runs to 654 pages, so the summary given here is hardly complete. A foreword written by Mitchison for the original 1930s text gives the time frame as “between the years 228 BC and 187 BC”. Marob is a construct entirely Mitchison’s own, and would make a few other appearances in her fiction – for instance, in the 1952 novel Travel Light. In her introduction to the 1990 Canongate edition, she situated it somewhere along the Black Sea coast. Several details of her inspiration help us to pin things down a little more precisely. In the same introduction, she refers to:

“The people who lived thereabouts [who] are vaguely called Scythians; one of the few things we know about them is that they made astonishingly beautiful objects, mostly bronze. You can see a few… in the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad.”[5]

Mitchison made a trip to the Soviet Union in the 1930s, including a visit to Leningrad. She describes portions of this, including the kurgans (a sort of burial mound) in the Crimea in her 1979 memoir of the 1920s and ‘30s entitled You May Well Ask. In the same book she also directly identifies several of the artefacts in Leningrad as being the work of Berris Der. She notes there that “Marob [is] on the shores of the Black Sea, somewhere to the north of the Danube delta, with a Graeco-Scythian culture.”[6] The inland raiders of the migratory ‘Red Riders’ are perhaps a more purely Scythian presence.

Corn King was written at the time the Cambridge Ancient History (1924–39) was coming out. In her introduction to the 1990 Canongate Classics reprinting of the novel, Mitchison mentioned her correspondence with the Classicists Sir Frank Ezra Adcock (1886–1968, one of the main editors of the Cambridge Ancient History) and Sir William Woodthorpe Tarn (1869–1957, who wrote extensively on Hellenistic history).[7]

The Cambridge Ancient History has several sections relevant to Corn King, notably discussions of Crimean archaeological sites,[8] the Scythians of Book Four of Herodotus’s Histories (who grow corn for sale rather than their own consumption), the Greek-founded Bosporan Kingdom (in Part V of Corn King, the Greek merchant Hyperides speculates that Marob was once a Greek colony)[9] and the art produced by the Bosporans as well as the Scythians.[10] Tarn’s chapter on the Greek Leagues and Macedonia includes conclusions and descriptions of the situation prior to and under Cleomenes III that might have come straight out of Corn King.[11] The other major source (again mentioned in Mitchison’s 1990 introduction) is James Frazer’s 1890 work The Golden Bough, with its comparison of myth and religion and images of sacred (often sacrificial) kingship and its association with the cycles of the harvest.

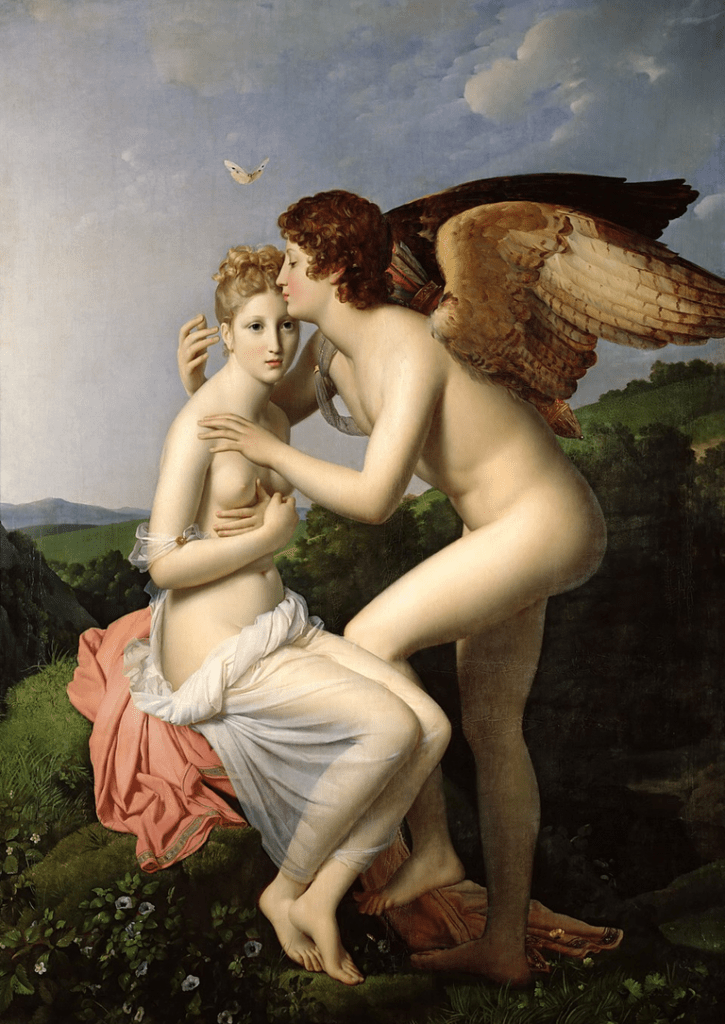

Till We Have Faces is far shorter than Corn King (320 pages in the Collins Fount Paperbacks 1989 edition). The story grows out of the myth of Cupid and Psyche, as recounted by Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (AD c.124–80) in his picaresque novel The Golden Ass. The nameless distant land described in Books Four and Five of The Golden Ass is fleshed out as Glome, which knows and worships Venus as Ungit.

Faces is framed as the memoirs of Orual, Queen of Glome, beginning with the birth of her sister Psyche, the third daughter of the King of Glome. She grows to adulthood in Glome and must in time be sacrificed to the “Beast of the Mountain” to satisfy Ungit. Orual’s love for her sister draws her to follow her up the mountain to rescue or bury her. When she learns that Psyche has been drawn into marriage with a faceless figure, she resolves to bring her out of her delusions – and thus pushes into motion the events of Apuleius’ story.

The perspective and narrative remain Orual’s throughout, down to dreams and visions; unlike in Apuleius, the sisters of Psyche survive into old age. A key secondary character is the Greek slave Lysias, known as the Fox, whom Orual’s royal father purchases as a tutor. His Stoic philosophy, his discussion of Greek culture (he specifically compares Ungit and Aphrodite) and his later counsel are all a major influence on Orual – whose rise to worldly power, mixed emotions about her sister Psyche, and inner debate on the nature and cruelty of the gods together form the bulk of the text.

Doris T. Myers in Bareface[12] dates Faces to between 300 BC and 187 BC on account of the texts acquired by the Fox for Glome’s small royal library – including Euripides, Homer, Heraclitus and Aristotle[13] – as well as the great powers mentioned (or not mentioned) in Orual’s memoir. Glome itself is in distant contact with Greece, through intermediaries. While it is on a river, it has no coastline, nor is any coastline mentioned for its neighbours Caphael and Phars. It has a similar range of flora and fauna to Marob, though Lewis spends less time on material culture than Mitchison does. He is however clear that Glome is “on the borders of the Hellenic world”. It would be difficult to place it exactly from the text,[14] but the mention of fights with ‘The Wagon Men’ on the other side of the Grey Mountain suggests that it is fairly near to the plains of Eastern Europe and Scythia. Reference to the Persian Great King[15] perhaps place it further south than Marob – a little to the north of the Caucasus, perhaps (a guess with which Myers agrees).[16]

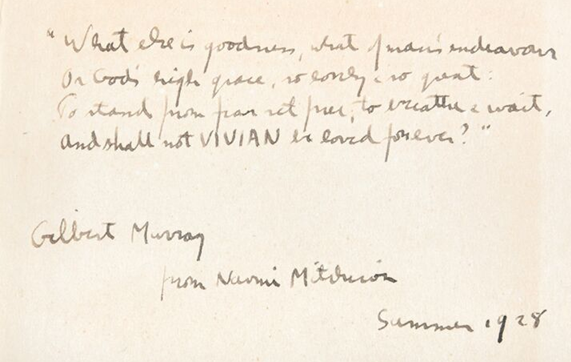

Corn King and Faces were published over twenty years apart, which is more than enough time for Lewis to have read the former and written the latter. He certainly knew of Mitchison: his library contained Black Sparta and When the Bough Breaks.[17] Lewis mentions her work several times in his letters: one to Arthur Greeves of February 1932 discusses Black Sparta, in which Lewis says that he doesn’t “know any historical fiction that is so astonishingly vivid and, on the whole so true.” However, he decries her “obvious relish” in cruelties as “morally wicked”. “Still”, he concludes, “she is a wonderful writer and I fully intend to read more of her when I have a chance.”[18] However, in a letter of July 1942 to Sister Penelope CSMV he says that he “gave up on N.M. some time ago because of her dwelling on scenes of cruelty. But I recognise real imagination, and a sort of beauty in the writing.”[19]

In 1950, Lewis’ friend Idrisyn Evans finished a book called The Coming of a King, aimed at a younger audience, as many of Mitchison’s stories were. In a letter in August 1951, Lewis wrote to Evans saying that it was “a great thing to put that idea of the Stone Age… into Boys’ heads instead of [H.G.] Wells’ or Naomi Mitchison’s.”[20] Of course, while Lewis might have worked to stem Mitchison’s influence, he was happy to recommend her (with caveats), as in a letter of August 1959 to a young American fan called Joan Lancaster.[21] The 1974 biography of Lewis by Roger Lancelyn Green (1918–87, an author of myths and historical fiction for children himself) and Walter Hooper (1931–2020, Lewis’ secretary in his last year) describes the writer’s fondness for historical fiction thus:

“Modern interpretations of the classical world, were… welcome, and Lewis was an enthusiastic reader of Mary Renault’s The King Must Die and The Bull from the Sea, and was even more impressed by the former after visiting Knossos in 1960; and Naomi Mitchison’s stories such as The Conquered were also favourites.”[22]

On the whole, it seems right to say that Mitchison was a minor influence on Lewis; on the other hand, I would be unwilling to claim that Corn King was responsible for Faces, or that Faces was a direct response to Mitchison’s work. This is especially clear when one compares how the two treat the pre-Christian world.

It is worth mentioning one item that may be an exception. We know that Lewis read Black Sparta. This is a series of short stories and associated poems, rather along the lines of one of Kipling’s books. It is set between 500 BC and 370 BC, largely in and around Sparta, though with stories set in several other parts of the Greek world. One of these, “The Epiphany of Poieëssa” (connected to Mitchison’s 1924 work When the Bough Breaks), deals with the interruption of a religious ceremony for Hera on the island of Poieëssa. However, Hera is referred to as Hera Parthené (from the Greek parthenos, “maiden”; the word is more often associated with the goddess Athena, whose main temple in Athens is of course the Parthenon) and bathes in the waters of the sea to restore her virginity (something more obviously associated with Aphrodite at Paphos). This is an atypical (or prototypical) Hera, to say the least.

The all-female ceremony is interrupted and the statue of Hera is broken. Nikaro, the long-time cult priestess laments at this, saying: “They’ll make a new Hera, a big marble one, and paint her blue-eyed and golden-haired.” She is convinced to run away with Timas (a male onlooker, but not the one who invaded the ceremony). He has embraced a form of abstract monotheism, turning away from (if not actively spurning) ceremonies like those depicted. The discussion of worship – and even the acquisition of a new statue for a hitherto nebulously limned goddess – bears comparison with certain sections in Faces in and around the temple of Ungit towards the end of Orual’s reign. This said, Lewis did have an affinity for the image of the transformation of a female statue – as in discussions of the statue of Hermione in the climax of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale.[23]

There is some overlap between Corn King and Faces, but that they ultimately do very different things. Corn King travels farther, lasts longer and lacks the central tentpole of a myth to hang things on. The Frazer-derived connections it makes point to an underlying culture rather than a single myth such as Cupid and Psyche. It is further distinct from Faces in that it regularly returns to real historical events, such as the reign of Cleomenes III, or attested physical locations, including Ptolemaic Egypt. Mitchison is more interested in historical artefacts; we have noted above the identification of items in the Hermitage Museum with the work of Berris Der.

Berris’ own life and work as an artist is also of importance within the text of Corn King: the reader finds him awestruck by, then slowly adjusting to, and pushing back against, Greek designs and artistic techniques. This overlaps with comments in The Cambridge Ancient History about the Bosporan Kingdom and the art it produced.[24] Berris Der aside, Mitchison has made her characters in Corn King quite conscious of the material culture around them. This emphasises both the historical finds she was familiar with and the state of life for those in a pre-industrial civilisation, for whom the mere production of cloth – let alone of garments – could be quite an undertaking. An illustration may usefully be found in the Gold of the Great Steppe exhibit appeared at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in 2021:

Mitchison’s approach to the reign of Kleomenes and his failed revolution in Sparta reflects her own sconcerns in the early 1930s. The Spartan King is thrust into exile, his (relatively!) egalitarian efforts apparently being to no avail. It should be no surprise that this seems to have something to do with Mitchison’s own politics, particularly her concerns for the state of the Labour Party and the Fabian Society’s cause (to say nothing of the Soviet Union, with which she never quite came to identify). This impression is reinforced by her comments in the 1990 introduction to Corn King, which indicate her nervousness at the time of writing with the shadow of Fascism in Europe.[25] These are not Lewis’ politics, nor is this his approach in Faces.

There are also the implications of what Mitchison creates out of Marobian ritual and belief, and what this lays bare when characters from Marob move through Greece and Egypt. The ritual of sowing and harvesting vary greatly between the three different cultures depicted in the novel (to say nothing of the three different biomes). There is the emerging image of Kings who must die for their people – a creed absorbed by Tarrik and lived out by Kleomenes. The death of the latter shares similarities with the Easter Narrative, which Mitchison implies is the cumulative effect of the underlying Proto Indo-European harvest myth working itself out and gradually changing over time in Greece and Marob, with the visual and earthy culture of Marob responding to Hellenic abstraction and philosophy.

These similarities are highlighted by the death of Kleomenes: he serves twelve companions at his last supper, and after his death is displayed on a cross; a snake even ascends the cross in a clear reference to the Brazen Serpent of the Book of Numbers.[26] Berris Der will even depict his death, and his choice of images (the dinner of twelve with bread and wine,[27] a procession with a young man on a colt and waving branches,[28] women mourning over a dead son, the “stake with its cross-piece and the snake coiled on it”[29] – scenes rather like those of Christian art over the centuries) will go on to spread the memory and cult of a half-remembered Kleomenes. Such associations are scarcely present in Faces, whatever the growing fame and divinity of Psyche. Faces, of course, has one central myth, one main locale in the shape of Glome, and the distinct perspective of one main character (there is no comparison of Tarrik with Erif Der). Indeed, that Orual is rarely thinking of things truly from another’s point of view is something of a feature of the plot. Unlike Corn King, we do not have an introduction written decades later – but we do have a letter of February 1957 written to Professor Kilby of Wheaton College (Clyde Samuel Kilby, 1902 –86), in which Lewis is good enough to detail his aims and ideas around Faces. Lewis begins:

“the levels [in Faces] I am conscious of are these.

(1) A work of (supposed) historical imagination. A guess at what it might have been like in a little barbarous state on the borders of the Hellenistic world of Greek culture, just beginning to affect it. Hence the change from the old priest… to Arnom; Stoic allegorizations of the myths standing to the original cult rather as Modernism to Christianity (but this is a parallel, not an allegory). Much that you take as allegory was intended as realistic detail. The wagon men are nomads from the steppes…

(2) Psyche is an instance of the anima naturaliter Christiana [naturally Christian soul] making the best of the Pagan religion she is brought up in… She is in some ways like Christ because every good man or woman is like Christ…

(3) Orual is (not a symbol) but an instance, a case of human affection in its natural condition, true, tender, suffering, but in the long run tyrannically possessive…

(4) Of course I had always in mind its close parallel to what is probably happening at this moment in at least five families in your home town. Someone becomes a Christian, or in a family nominally Christian already does something like becoming a missionary or entering a religious order.”[30]

Both Corn King and Faces are works of historical imagination, of course. That Barris Der ends up creating the images described above might suggest something quite close to anima naturaliter Christiana, though one suspects that Mitchison might say that this was missing the point. It should be noted that the consciously Christian Faces is far less direct with its parallels than Corn King. The parallel with conversion does not readily appear to exist in Corn King, though similar sentiments and ideas are expressed in the awkward interactions of Greece and Marob. The need of grace – or something like it – may be behind some of Mitchison’s ideas, but is not part of Corn King. It is however, fairly clearly a work of historical imagination, and many of those involved might perhaps be would-be Christians before Christ.

The interactions of Greece – or at any rate, the Fox – and Glome also may be compared with those of Greece and Marob. The artistry of Greece (in the shape of a new statue of Ungit) finds its way to Glome provoking a response from natives of that kingdom. Likewise, the Fox’s efforts also manage to bring about a set of changes. This relationship between the word and the image, the cold and the hot, the disciplined and the sensual was explored earlier in Lewis’ allegory The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), in which the pilgrim John must move through a series of lands which either are part of the Northern or Southern tendency. These are characterised thus by Lewis’ introduction:

“The Northerners are men of rigid systems whether sceptical or dogmatic, Aristocrats, Stoics, Pharisees, Rigorists, signed and sealed members of highly organised ‘Parties’. The Southerners are by their very nature less definable; boneless souls whose doors stand open every day to almost every visitant, but always with the readiest welcome for those, whether Maenad or Mystogogue, who offer some sort of intoxication.”

Such ideas have counterparts of a kind in Corn King, but also indicate a different an older source of inspiration for Lewis, who could revisit them profitably in Faces, seeing human beings grapple once again with Divinity, Mercy and Justice.

Mitchison’s visit to Russia and what she saw in the Cambridge Ancient History helped inspire the creation of Marob. Lewis saw a need for proximity to and distance from Greece in his work – close enough so that the myth of Psyche could be transmitted from Glome to Apuleius to write The Golden Ass, but far enough to maintain some level of mystery. Both authors enjoyed Classical educations (though one wouldn’t call either of them Classicists) and maintained an interest in the ancient world throughout their lives: Mitchison wrote repeatedly on the period and Lewis could scarcely avoid discussing myth and cultural inheritance in his chosen academic subject.

The influence of Greece and the Mediterranean World is felt differently in Corn King and Faces: Marob gains Hellenic art and philosophy via the personal means of Sphaeros, while Glome gains literature via the Fox. Glome and Marob alike, as distant from and tied to Greece, also offer a parallel with Britain, with its own ‘barbarian’ inheritance courtesy of the Anglo-Saxons, its distance from Greece (in time more dramatically than in space) and its (comparatively sparse) scattering of surviving texts from the period. The same sort of impulse led Dorothy L Sayers to refer to “our Mediterranean civilization, such as it is” in her 1940 address “Creed or Chaos?” [31] Whatever the differences between Mitchison and Lewis, and the different things they attempt in their novels, they do seem to have laid a similar and intriguing foundation for their ideas in these peripheral states in the shadows of the Hellenic world.

Edmund Racher, having spent some time in publishing, currently holds a minor position at Magdalen College, Oxford. Despite an MA in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, he has nursed an interest in the Classics from an early age. He has previously written for Antigone about both the twilight of Rome and the conquering sign of Constantine in 20th-century fiction.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Her brother was the scientist and occasional correspondent of Lewis’, J.B.S. Haldane (1892 –1964). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | ‘Corn’ here is used in the British sense, referring to wheat (or something very much like it) rather than maize. |

| ⇧3 | When referring to the character I write Kleomenes, when to the historical figure, Cleomenes. |

| ⇧4 | The decadence of Ptolemy’s court is epitomised in a dish at one of his banquets: ”Every guest had a marzipan crocodile about a foot long, dyed in natural colours and biting a naked man or woman made of white nuts appropriately stained with red in parts. The nut faces had all been carved separately by a Persian ivory-worker, each into a different and individual little mask of screaming horror. If you liked that sort of thing, that was the sort of thing you liked.” (Mitchison, The Corn King and the Spring Queen [Canongate, London, 1990] Pt. VIII, Ch. 5, 639). |

| ⇧5 | Leningrad was founded as St Petersburg, bore the name Petrograd for a time and is now once more St Petersburg. |

| ⇧6 | Naomi Mitchison, You May Well Ask: A Memoir, 1920-1940 (Gollancz, London, 1979) 165. |

| ⇧7 | Mitchison (as n.4) VII. |

| ⇧8 | The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. IV: The Persian Empire & The West, Ch. IV, Section VI, “The Black Sea and Its Approaches”, written by P.N. Ure (1879–1950). |

| ⇧9 | The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. VIII: Rome & the Mediterranean, 218–135 BC, Ch. XVIII, “The Bosporan Kingdom”, written by Michael Rostovtzeff (1870–1952). |

| ⇧10 | The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. III: The Assyrian Empire, Ch. IX “The Scythians and the Northern Nomads” Sections IV ‘Scythian Customs” and V ”Religion, Burial Customs”, written by Sir Ellis Hovell Minns (1874–1953). |

| ⇧11 | The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. VII: The Hellenistic Monarchies and the Rise of Rome, Ch. XXIII, “The Greek Leagues and Macedonia”, Section III, ”Agis IV of Sparta and Reform”. Compare Section VII, “Cleomenes III of Sparta and the Revolution”: “The old land-system of lots was in ruins and all the land belonged to comparatively few rich men, who had abandoned Spartan habits and become luxurious; there were many poor men who had lost their land, and, consequentially, under the Sparta constitution, their citizenship; the common meals were deserted, as the rich would not and the poor could not participate.” |

| ⇧12 | Doris T. Myers, Bareface: A Guide to C.S. Lewis’s Last Novel (Univ. of Missouri Press, Columbia, MI, 2004). Bareface was the name initially used for Faces until the publisher suggested it would put readers in mind of a Western. |

| ⇧13 | Aristotle’s Metaphysics is referred to in Part I, Ch. 20 of Faces as “a very long hard book (without metre) which begins All men by nature desire knowledge.” |

| ⇧14 | A review encountered in the course of writing placed Glome in the Levant. |

| ⇧15 | Till We Have Faces, Part II, Ch. 1. |

| ⇧16 | Myers, Bareface (as n.12) 165: “It seems plausible that Glome is in Scythia, wherever that is… In more modern terms, the kingdom of Glome could have been in south Russia, but it could also have been farther west, closer to the Danube.” |

| ⇧17 | The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College once had an inventory of Lewis’ library available online. This is now only available via the Internet Archive, or in somewhat different form by a page on LibraryThing.com. |

| ⇧18 | The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis (3 vols, HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco, CA), Vol. 2, 52. |

| ⇧19 | Ibid., Vol. 2, 527. |

| ⇧20 | Ibid., Vol. 3, 133. |

| ⇧21 | Ibid., Vol. 3, 1218. |

| ⇧22 | Roger Lancelyn Green & Walter Hooper, C.S. Lewis, A Biography (Collins, London, 1974) 294–5. |

| ⇧23 | Compare also the scene in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in which Aslan breathes life back into petrified creatures. |

| ⇧24 | See The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. VIII, Ch. XVIII, ‘The Bosporan Kingdom’, Section V ”Civilisation and Art”, written by Michael Rostovtzeff. |

| ⇧25 | Corn King (as n.4) X. |

| ⇧26 | The Gospel of John makes a clear connection between the Serpent and Jesus, and Christian art has often depicted the Serpent on a pole with a crosspiece. |

| ⇧27 | Ibid., Pt. VIII, Ch. 4, 634: “The first picture was of the fast at the prison, the last eating together… The King was in the centre, with Panteus beside him, leaning against his breast… The picture was grave and balanced… There was food on the tables, picking up the same colours. The Spartans drank wine and broke bread with curious fixed gestures.” |

| ⇧28 | Corn King (as n.4) Pt. VIII, Ch. 4, 634: “Hippitas riding on the colt… and the crowd behind him shouting too and waving branches and coloured cloths. The one short moment of triumph before the end.” |

| ⇧29 | Ibid., Pt. VIII, Ch. 4, 635. |

| ⇧30 | Lancelyn Green and Hooper (as n.22) 266. |

| ⇧31 | Collected in the volume Creed or Chaos? And Other Essays in Popular Theology (Methuen, London, 1947). Sayers’ connection of the Classical world to 20th-century Britain has been discussed on Antigone before here. |