Piotr Stępień

In this article, I invite you to join a game in which we will treat the narrative world of Homer as a simulation – a computer game where you participate from a first-person perspective. Along the way, through this hopefully playful exploration, we will attempt to address – at least partially – a question that has puzzled us, lovers of Greek, since antiquity. This question revolves around the factors that determine word order in this beautiful language.[1]

One key aspect of the issue can be framed as follows: why does the Greek equivalent of “right hand’’ sometimes appear as a) δεξιὰ χείρ (dexia cheir, lit. right hand) and at other times as b) χεὶρ δεξιά (cheir dexia, lit. hand right)? Scholars have offered various answers to this question. Currently, it is widely accepted that the difference between a) and b) results from how Greek organizes information in a sentence, with certain parts given more saliency or importance than others.

The properties of this information structure, particularly as they pertain to syntactic pairings of adjectives and nouns (so-called noun phrases), dictate that the adjective appears first when it conveys information deemed more salient than that of the noun. This occurs, for example, when the adjective “right” is contrasted with “left” in the context. Conversely, when the noun comes first, it is assumed that either the noun carries especially important information, or the entire phrase is “neutral”.[2]

Linguists studying the information structure of Greek typically adopt either the perspective of a viewer observing states of affairs expressed in the sentence, or that of the author of the text formulating a linguistic utterance directed at the reader or listener – analogous to the speaker-addressee relationship. Such an approach, as is evident, does not entail a systematic analysis of the perspective and motivations intrinsic to the characters within the text. In the game I propose, you are expected to fully immerse yourself in the Homeric storyworld (because, after all, every literary endeavor should begin with Homer!). You will become a fully-fledged inhabitant of this world, “stepping into” the character whose perspective the narrative currently adopts. In other words, you will become the observer who perceives reality from the egocentric (or first-person) perspective.

From this vantage point, you will obviously be unaware that you think and speak in dactylic hexameter verse or that you employ a formulaic style. Instead, you will notice, for instance, that your right hand is on your right side. This is not a trivial observation, because as a simultaneous recipient of the text, you are by no means obliged to adopt such an egocentric perspective when reading something like, “he had come to the swift ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter.” Just as easily, you could observe what you are reading about from the side, from the front, or from above – much like most readers likely do.

Once you step into the mind and body of a given character, you will realize that the Homeric storyworld feels very much like your own. Just like in this world, another person is your mirror reflection – provided you both share the default perceptual arrangement. This term refers to real or imagined situations in which, as an observer, you encounter, observe, and get to know other people or the world around you. By default, you face the things you are observing. Similarly, in the act of meeting or interacting with another person, you typically stand on roughly the same plane, facing each other.

The prerequisite for the ability to establish a default perceptual arrangement is being in a default state of perception. In this state, among other things:

a) you correctly identify directions on the perceptual axes;

b) you possess a default (i.e. healthy) body and mind;

c) you think and act in accordance with your nature – usually encoded in your name – and use objects in accordance with their nature and purpose.

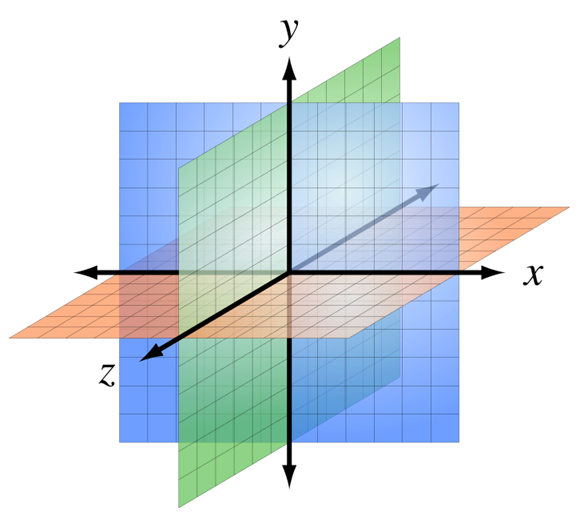

Another important and inherently familiar feature of the Homeric storyworld is its spatial three-dimensionality. This characteristic allows nearly everything you see to be described using at least one of the three perceptual axes: LEFT-RIGHT, DOWN-UP, and BACK-FRONT. Within these axes, the positive directions RIGHT, UP, and FRONT correspond to one another. Similarly, the negative directions LEFT, DOWN, and BACK align with each other.[3]

At this point, as a reader of this article with an interest in Greek grammar, you might rightly ask, “What the heck is going on? Why am I reading about mirror reflections and Cartesian coordinates in an Antigone article about grammar?” For two complementary reasons. First, in the Homeric narrative world, each direction on the perceptual axes is associated with specific values and symbolism. This means that, for example, looking to the right directs your attention to your own right hand and the left hand of another person in the default perceptual arrangement. But you also look to the right whenever paying attention to everything culturally – and perhaps evolutionarily – associated with the right side. This, of course, refers to the widespread tendency in many (if not all) cultures to attribute positive values to the right side, and negagtive to the left. For most people the right corresponds to their stronger, more capable, and therefore more valuable hand. This kind of thinking also prevails in the Homeric storyworld.[4]

The second reason is the hypothesis on which this article focuses. Its “academic” version is relegated to a footnote,[5] allowing us to concentrate here on its more relatable form. It suggests that the observer’s egocentric perspective and emotional-cognitive stance are schematically recorded in grammatical form. In relation to the problem of word order in the Homeric noun phrase, this simply means that the AN structure (right hand) reflects a different direction of your attention as an observer and a different emotional-cognitive stance than the NA structure (hand right).

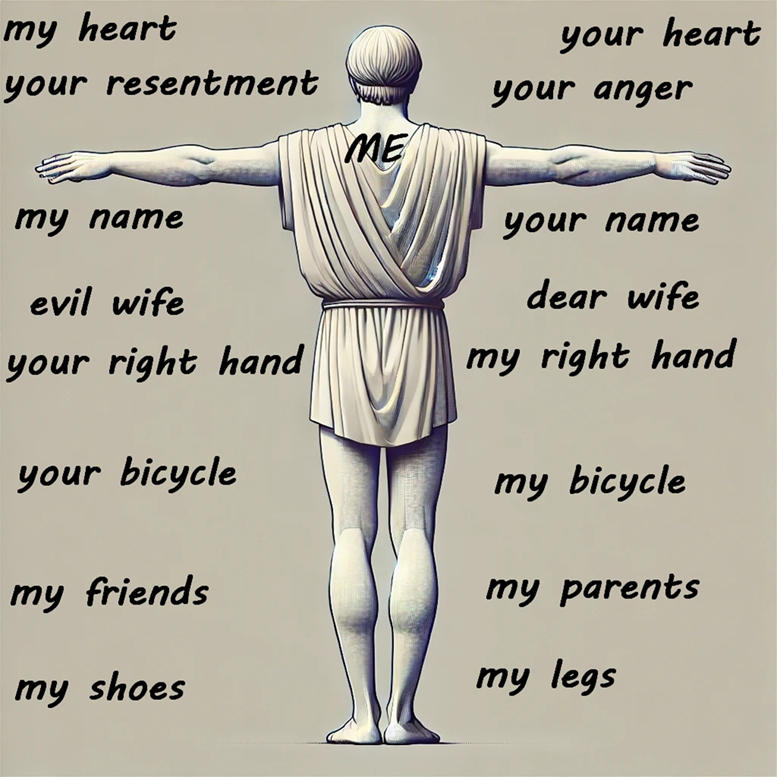

From this it follows that the adjective functions as an indicator of direction understood in both spatial and symbolic terms. When it appears to the left of the noun, it may signal that your attention is directed toward your left hand, your heart and thus your emotions, thoughts and identity, or toward the right hand of the person with whom you share the default perceptual arrangement. Let us call such a being or thing the observed. Below are the rules derived from this approach. The rules 1R and 1L apply to observer’s default perceptual state.

1R. A right-oriented NA phrase reflects the observer’s emotional-cognitive stance and attention directed

a) toward their own positive direction (i.e., RIGHT, UP, FRONT) on one of the perceptual axes or

b) toward the negative directions (LEFT and BACK) of the observed.[6]

1L A left-oriented AN phrase reflects the observer’s emotional-cognitive stance and attention directed

a) toward their own negative direction (i.e., LEFT, DOWN, BACK) on one of the perceptual axes or

b) toward the positive directions (i.e., RIGHT and FRONT) of the observed.

2RL If the observer is not in the default state of perception and/or does not establish a default perceptual arrangement, a right-oriented NA phrase replaces a left-oriented AN phrase, and vice versa.

The rules postulate that grammatical form serves as a schematic representation of both (i) the observer’s spatial perception – correct (1R, 1L) or incorrect (2RL) and (ii) their awareness (1R, 1L) or unawareness (2RL) of themselves and the surrounding world. The spatial aspects of these rules are simple and obvious. But what does it mean that “the NA phrase reflects the observer’s emotional-cognitive stance”?

According to 1R, the NA phrase can appear in situations where, as a Homeric observer, you refer to someone or something on which your existence and identity directly depend, or which exists and functions as a result of your existence. Such beings and things include, for example: your body parts, your soul, your parents, your children, your wife/husband (because in the act of sexual union, they become part of your body), your leader or king (because their existence defines your identity as a subject), your herald (because they carry your voice, whose existence depends on your body), your home and homeland when you are at home (as they define your identity as someone born, living, and originating from somewhere), various objects, such as your sword (as it defines your identity as a warrior), your bow (if you are an archer), your scepter (if you are a priest or leader), or your ship (as it requires your body to function as a means of transport). Since the NA phrase records your attention directed toward the heart of another person in the default perceptual arrangement, and the heart is the emotional center of a Homeric character, this means that on your right side, you observe the healthy emotions of others.

According to 1L, the AN phrase can appear in situations where you refer to someone or something that neither your existence nor identity directly depends on, or which neither depends on nor functions as a result of your existence. Such beings and things include, primarily, strangers, but also friends, companions, and, apparently, siblings. These also include objects and elements of the external world that are more or less indifferent to you. The AN phrase may also appear when you experience healthy emotions, as their place is in the heart, which is located on the left.[7]

As for 2RL, the observer does not establish a default perceptual arrangement with the observed when, for instance, one of them has their back turned to the other. The observer also establishes a default perceptual arrangement with themselves, so to speak, when they are at home and in their homeland. If this is not the case, these concepts are described in accordance with 2RL (and thus not in line with 1R). If the observer is not in the default state of perception, it primarily means that their perception of reality is less insightful, more insightful, fuller, poorer, distorted, or simply different from what the majority perceives. This occurs in situations where the observer:

a) is under the influence of strong emotions – both negative and positive;

b) is experiencing physical or mental suffering;

c) is in an altered state of consciousness – e.g., sleeping or being drunk, or dead;

d) lies or possesses more/less knowledge than most inhabitants of the Homeric storyworld or the given scene.

Armed with these three rules, we can finally step into the world presented to us by Homer. Let us begin with a series of short scenes, whose specific nature will allow you to familiarize yourself with the basic mechanics of our game. All of them revolve around perception along the LEFT-RIGHT axis.

(1) αὐτὰρ Ὀδυσσεὺς

χείρʼ ἐπιμασσάμενος φάρυγος λάβε δεξιτερῆφι (Od. 19.479–80)

As for Odysseus, he felt for Eurycleia’s throat with his right hand, seized it.[8]

As Odysseus, you grab Eurycleia by the throat. The NA structure – according to 1R(a) – faithfully registers the fact that you are using your right hand. It is also important to note that there is no indication in the immediate context that your perception of reality at this moment is in any fundamental way distorted or generally different from Eurycleia’s perception of reality. If that were the case, this fact would be revealed at the level of grammatical form, which functions almost like a lie detector. Its operation is demonstrated in the next example.

(2) ὣς ἄρ’ ἄτερ σπουδῆς τάνυσεν μέγα τόξον ᾿Οδυσσεύς.

δεξιτερῇ δ’ ἄρα χειρὶ λαβὼν πειρήσατο νευρῆς. (Od. 21.409–10)

Odysseus strung the enormous bow without effort. He grasped it firmly in his right hand and tried the string.

In this scene, you test the tension of the bowstring with your right hand, preparing to slaughter the suitors. They have no idea who you really are or what you are planning. If they could access your mind, they would immediately realize that something is very wrong. The grammatical form AN – in accordance with 2RL – reveals that you perceive your right hand as if it were your left! This record of a cognitive error is nothing more than the lie detector’s response to the fact that, by concealing the truth (or possessing greater knowledge) of who you are, your perception of reality is dramatically different from that available to most participants in the scene.

As for the great bow itself (μέγα τόξον, mega toxon), you do not consider this deceptive weapon to be your true attribute (AN, 1L(a)). And rightly so, as archers – like the foolish Pandarus, for example – do not enjoy a favorable reputation in your world.

Alright, now that we know how to use our hands, let’s have a bit of fun and try to take someone out.

(3) Τληπόλεμος δʼ ἄρα μηρὸν ἀριστερὸν ἔγχεϊ μακρῷ

βεβλήκειν (Il. 5.660–1)

Tlepolemus had hit Sarpedon’s left thigh with his spear

(4) δεξιτερὸν κατὰ μαζὸν ὀϊστῷ τριγλώχινι

βεβλήκει· (Il. 5.393–4)

[Heracles] struck her right breast, using an arrow with a triple barb

(5) βεβλήκει γλουτὸν κατὰ δεξιόν (Il. 5.65)

[Meriones] speared him through his right buttock

(6) ὡς δʼ ὅτε τίς τε κύων συὸς ἀγρίου ἠὲ λέοντος

ἅπτηται κατόπισθε ποσὶν ταχέεσσι διώκων (Il. 8.338–9)

As when a dog pursues a lion or wild boar – his paws are quick, he follows close behind

In (3), as Tlepolemos, you strike Sarpedon’s left thigh with a long spear, establishing a default perceptual arrangement with him in the duel. You act in accordance with 1R(b), as you observe his left thigh on your right side, as revealed by the NA phrase. Rule 1R(a), on the other hand, describes how you perceive your spear. You throw it with your hand, making it an extension of your body. Hence, the NA phrase.

In (4), as Heracles, you strike Hera in the right breast. Hera’s right side, in the default perceptual arrangement, is on your left, which is why, in accordance with 1L(b), your perspective is described using the AN phrase. Furthermore, since you naturally use your right hand to hold the arrow and draw the bowstring, the released arrow becomes an extension of your hand. Hence, the NA phrase.

In (5), it gets even more amusing, as Meriones, you strike Phereclus in the right buttock. This shows that you do not form a default perceptual arrangement with him, as Phereclus is turned with his back to you. Thus, 2RL applies. In such an arrangement, his right side corresponds to your right, which is reflected in the NA phrase.

In (6), you are a dog chasing wild game. According to 1R(a), the NA phrase describes your legs because they are part of your body. The wild boar (συὸς ἀγρίου) is not your parent, offspring, nor does your identity as a dog depend on it, etc. So why is your cognitive stance toward the fleeing boar described with the NA phrase instead of the expected AN? The answer is 2RL. When it flees ahead of you, it is turned with its back to you – just like Phereclus in (5).

After the chase, you are probably thirsty. Time to have a drink.

(7) τοὺς δὲ μετ’ ᾿Ατρεΐδης ἔκιε ξανθὸς Μενέλαος,

οἶνον ἔχων ἐν χειρὶ μελίφρονα δεξιτερῆφι,

ἐν δέπαϊ χρυσέῳ, ὄφρα λείψαντε κιοίτην. (Od. 15.147–9)

And Menelaos Atreïdes, with his auburn hair, went with them, holding a golden cup full of wine with a hint of honey in his right hand, so that they could pour libations before setting out.

As Menelaus, you are bidding farewell to Telemachus, who is returning home. You hold in your right hand a golden cup filled with delicious wine. Each emboldened phrase is modified by an adjective consistently placed after the noun (NA). For scholars focused on information structure, this probably indicates that the adjectives do not carry significant information in this context, and all these phrases might be considered neutral. Alternatively, this approach might assign critical importance to the nouns as carriers of particularly relevant information.

From your perspective, however, things look different. Since you are using your right hand (χειρὶ δεξιτερῆφι, cheir dexiterēphi), your attention is directed to the right, which is registered by the NA phrase. And what about the cup? Just as the default function of a ring depends on the existence of a finger, the default function of a cup depends on the existence of your body, specifically your hand – by default, the right one. For this reason, if your attention is directed toward your cup, it is described with an NA phrase, as if it were almost a part of your body. Mutatis mutandis, if your attention is directed toward the cup of a person with whom you share a default perceptual arrangement, it is described with an AN phrase (which, of course, does not mean that a phrase describing a cup – or anything else – must include an adjective!). All of this assumes that you are in a default state of perception. In a similar valedictory scene involving a cup, you participate as Hecuba, the wife of Priam, who is bidding farewell to her husband as he embarks on a dangerous mission to Achilles’ tent.

(8) ἀγχίμολον δέ σφ’ ἦλθ’ ῾Εκάβη τετιηότι θυμῷ

οἶνον ἔχουσʼ ἐν χειρὶ μελίφρονα δεξιτερῆφι

χρυσέῳ ἐν δέπαϊ, ὄφρα λείψαντε κιοίτην· (Il. 24.284–5)

Hecuba, heartsick, came to them. She held in her right hand a golden cup of wine as sweet as honey, so that they could pour libations for the journey.

Once again, you hold a cup of wine in your right hand. This time, however, as recorded in the grammatical form AN (χρυσέῳ ἐν δέπαϊ, chrūseōi en depaï), the way you perceive the cup proves that the image of reality in your mind is distorted. The reason for this is the psychological suffering you are experiencing (τετιηότι θυμῷ, tetiēoti thūmōi), which prevents you from being in a default state of perception.[9]

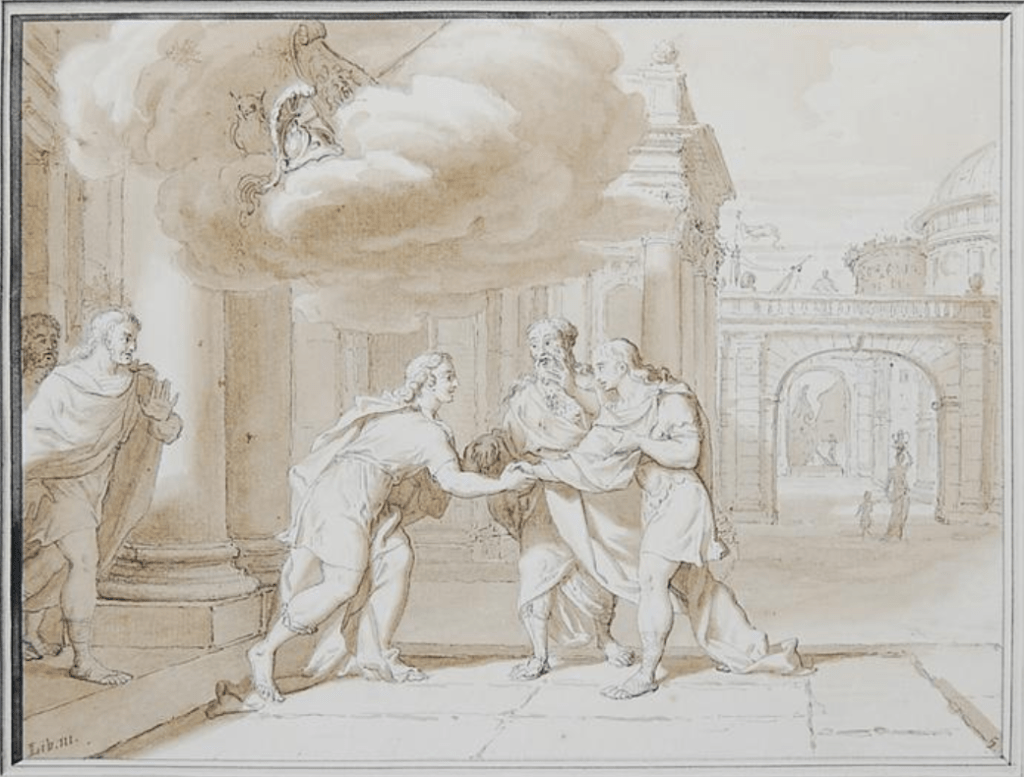

Taking another person’s perspective involves imagining oneself in another’s shoes (i.e., body and mind). Numerous studies show that this process fosters an increased sense of empathy and compassion toward others, which, in turn, strengthens our social bonds.[10] My research to date suggests that there is at least one distinct and recurring type of situation in which the observer adopts the egocentric perspective of the observed in the Homeric storyworld. This occurs in acts of requests, encouragement, persuasion, and sometimes commands. In other words, these are situations where you wish for your will (that is, a specific content of your mind) to become the will of the other person. By adopting their perspective, you effectively enter their mind and, from that position, try to read it or attempt to suggest that they think, feel, and perceive reality as you do.

Such are the tricky rules of the game, I’m afraid. Let us test them in a scene where, as Telemachus, you make an earnest plea to Nestor for information about the circumstances of Odysseus’ death.

(9) τοὔνεκα νῦν τὰ σὰ γούναθ’ ἱκάνομαι, αἴ κ’ ἐθέλῃσθα

κείνου λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον ἐνισπεῖν, εἴ που ὄπωπας

ὀφθαλμοῖσι τεοῖσιν. (Od. 3.92–4)

For this reason I have come to your knees, in case you might be willing to inform me about his unfortunate death, whether you saw it somewhere with your own eyes.

Your attention first shifts to Nestor’s knees, with whom you form a default perceptual arrangement, and then to his eyes. In the first case, your perception is registered by the AN phrase in accordance with 1L(b), because you direct your attention to the body part of the observed person that they observe on the positive pole of the perceptual axis. In the second, however, the NA structure registers your desire for Nestor’s eyes to somehow become your own, allowing you to see what he has seen, which is, in essence, the content of your request.

Well, we should be wrapping up, but, but… let’s play out one more delightful little scene.

(10) ὤρνυτ’ ἄρ’ ἐξ εὐνῆφιν ᾿Οδυσσῆος φίλος υἱός,

εἵματα ἑσσάμενος, περὶ δὲ ξίφος ὀξὺ θέτ’ ὤμῳ,

ποσσὶ δ’ ὑπὸ λιπαροῖσιν ἐδήσατο καλὰ πέδιλα (Od. 2.1–4)

Odysseus’ son got out of bed and put on his clothes. He slung his sword over his shoulder, tied his splendid sandals around his glistening feet.

It is morning, and as Telemachus, you rise from bed. Awakened, you perceive yourself as the ᾿Οδυσσῆος φίλος υἱός, beloved son of Odysseus. The grammatical form of the AN phrase reveals that during this process, your attention is directed to your left side. Evidently, the sense of being loved by your father resides in your heart, forming an integral aspect of your identity as a son in this scene.

Then you get dressed. You sling your sword over your shoulder and put beautiful sandals on your glisteningfeet. The structure of each emboldened phrase records what you see (your egocentric perspective) and how you perceive what you see (your emotional-cognitive stance). Thus, NA describes your feet in accordance with 1R(a), because they are part of your body, and you recognize them as such. On the other hand, the sandals are neither part of your body nor do they define your identity – after all, you are not ‘playing’ the role of a shoemaker.

Therefore, in this case, AN encodes what you see in line with 1L(a). The sword, however, is a different matter. As an indispensable attribute of a warrior – or here someone aspiring to that role (no offense!) – the sword is an element of your identity. Since you sling your sword over your right shoulder – as you do now, as a default right-handed warrior – it is described by the ‘right-handed’ NA. If, however, you were to sheath your sword, with the scabbard normally worn at the left leg, the sword would be described by the AN structure, in accordance with 1L(a). Here is an example:

(11) ῏Η καὶ ἐπ’ ἀργυρέῃ κώπῃ σχέθε χεῖρα βαρεῖαν,

ἂψ δ’ ἐς κουλεὸν ὦσε μέγα ξίφος, οὐδ’ ἀπίθησε (Il. 1.219–20)

Grasping the silver hilt with his strong hand, he pushed the big sword back into its scabbard.

As Achilles, you direct your attention to the sheath on your left, into which you slide a large sword, using your hand (NA, 1R(a)). Since the sword is now on the left side of your body, both its silver hilt and the sword itself are described using the AN structure, consistent with 1L(a). In this context, an NA phrase would indicate a cognitive error, possibly caused by intense emotions. However, in the scene from which these lines are taken, you are relatively composed – thanks to Athena, who tugged at your hair, diverting your attention from the object of your fury, Agamemnon.

I hope this Homeric game has brought you some joy and offered new perspectives. Exploring grammatical form according to the principles outlined in this article provides an almost tangible access to the world of Homeric narrative, a creation and extension of the human mind. Through this access, we uncover how deeply the grammatical form allows us to delve into human nature. Embedded within this form are simple, ancient, and increasingly forgotten truths about what it means to be human. Perhaps we should strive to rediscover these truths anew.

Piotr Stępień is a free spirit, ultra-distance cyclist, and a professor at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. He is currently developing his original hypothesis of syntactic deixis in the language of Ancient Greek poetry.

Further Reading

H.L. Pick Jr and L.P. Acredolo (edd.), Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research, and Application (Plenum Press, New York, 1983).

A.J. van Doorn, W.A. van de Grind and J.J. Koenderink (edd.), Limits in Perception: Essays in Honour of Maarten A. Bouman (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL).

J.F. Duchan, G.A. Bruder and L.E. Hewitt (edd.), Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective (Routledge, London, 2009).

C.J. Fillmore, Lectures on Deixis (Cambridge UP, 1997).

N. Felson, “The poetic effects of deixis in Pindar’s Ninth Pythian ode,” Arethusa 37 (2004) 365–89.

F. Licciardello, Deixis and Frames of Reference in Hellenistic Dedicatory Epigrams (De Gruyter, 2022).

Notes

| ⇧1 | For formal clarity, let me add that the issue discussed in this article pertains to the factors determining the word order within adjectively modified noun phrases in Homer. The proposed method of analysis of word order is the result of an original hypothesis that I am currently developing. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | This is currently the commonly accepted way of understanding word order determinants in the ncient Greek nominal phrase, as suggested by the encyclopedic entries “Noun Phrase” by H. Perdicoyianni-Paleologou, and “Word Order” G. Giovani and A. Celano in the Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics (vol. 2, G. K. Giannakis et al., Brill, Leiden, 2012). |

| ⇧3 | This indirectly refers to the Cartesian coordinate system we all know from elementary school. In this system, LEFT-RIGHT corresponds to the X-axis, where “left” represents the negative direction and “right” the positive. DOWN-UP corresponds to the Y-axis, with “down” as the negative direction and “up” as the positive. BACK-FRONT corresponds to the Z-axis, where “back” is the negative direction and “front” is the positive. |

| ⇧4 | A good man named Chris McManus wrote an insightful and engaging book Right Hand, Left Hand: The Origins of Asymmetry in Brains, Bodies, Atoms, and Cultures (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2002), which, among other things, addresses the cultural significance of the right and left in language, art, and religion. As a counterpoint, Howard Kushner’s book, On the Other Hand: Left Hand, Right Brain, Mental Disorder, and History (Johns Hopkins UP, Baltimore, MD, 2017), examines issues related to left-handedness in a scientific, historical, and cultural context. |

| ⇧5 | The structure of the adjectivally modified noun phrases in Homeric Greek is shaped by embodied cognitive processes, where syntax mirrors the observer’s bodily orientation, spatial perception, and emotional states, reinforced by culturally specific symbolic associations of left-right, down-up, and behind-front dichotomies. |

| ⇧6 | The DOWN-UP direction is not included in b) because a mirror reflection does not reverse it. In other words, it remains the same for both participants in the default perceptual arrangement. |

| ⇧7 | There are few exceptions to the rules presented here, mostly related to social hierarchy. One such exception is the noun πατήρ (patēr, father). It is used in accordance with R1 even for a man who is not the observer’s actual father. This is because “father” serves as a term of respect for an older man in whom the observer sees their own father. |

| ⇧8 | Passages from the Odyssey are translated by Charles Underwood, and those from the Iliad by Emily Wilson. |

| ⇧9 | Note that the metre also permits ἐν δέπαϊ χρυσέῳ (en depaï chrūseōi) here. Thus, the metre is not the reason why the lines ἐν δέπαϊ χρυσέῳ, ὄφρα λείψαντε κιοίτην and χρυσέῳ ἐν δέπαϊ, ὄφρα λείψαντε κιοίτην have a different grammatical form. |

| ⇧10 | See for example M.W. Myers and S.D. Hodges, “The structure of self–other overlap and its relationship to perspective taking,” Personal Relationships 19 (2012) 663–79; N.J. Goldstein, I.S. Vezich, and J.R. Shapiro, “Perceived perspective taking: when others walk in our shoes,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106 (2014) 941–60.; A.D. Galinsky, G. Ku, and C.S. Wang, “Perspective-taking and self–other overlap: fostering social bonds and facilitating social coordination,” Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 8 (2005) 109–24. |