Bradley Brincka

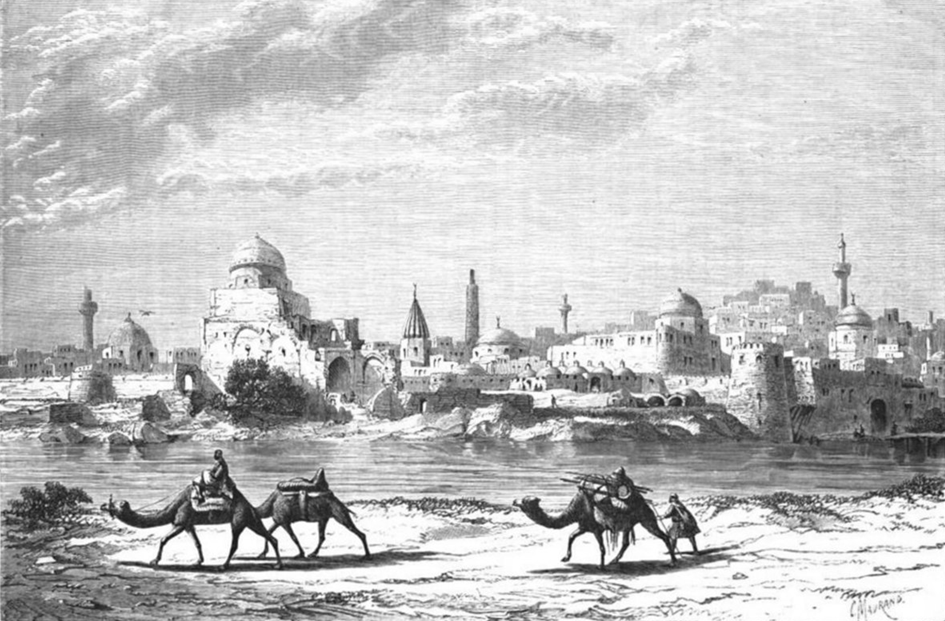

I had no particular interest in the Classics when first I went to war. It was the spring of 2017 on the outskirts of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. At that time, I was an ambulance driver with a medical outfit attached to an Iraqi armored brigade. The millenarian entity known as the Islamic State had proclaimed the establishment of a caliphate from that metropolis on the Tigris River three years earlier. Lady Fortune’s wheel was ever turning, though. Now the Iraqi army was laying siege to the city.

It was hard to think of Mosul as anything other than a haunted place. The modern city lay in the shadow of Nineveh’s ancient ruins, once the seat of a great empire. Among their many crimes, its iconoclastic occupiers had made a public spectacle of smashing Assyrian artifacts when overrunning the Mosul Museum in 2014. Since the start of the siege the previous October, the city had entered the unenviable gallery of history’s doomed urban centers, sentenced to the grim fate of a Troy or Carthage, and presaging the destruction of distant places such as Bakhmut and Gaza years later.

In light of the city’s slow-motion annihilation and its inhabitants’ agony and lamentations, it was not unreasonable to wonder whether the Islamic State’s act of archaeological vandalism had unleashed some kind of terrible curse. Perhaps the hubris and sacrilege had stirred those long-dormant gods of stone from their slumber, so that now Nineveh’s ancient goddess Ishtar could only be propitiated with a blood sacrifice.

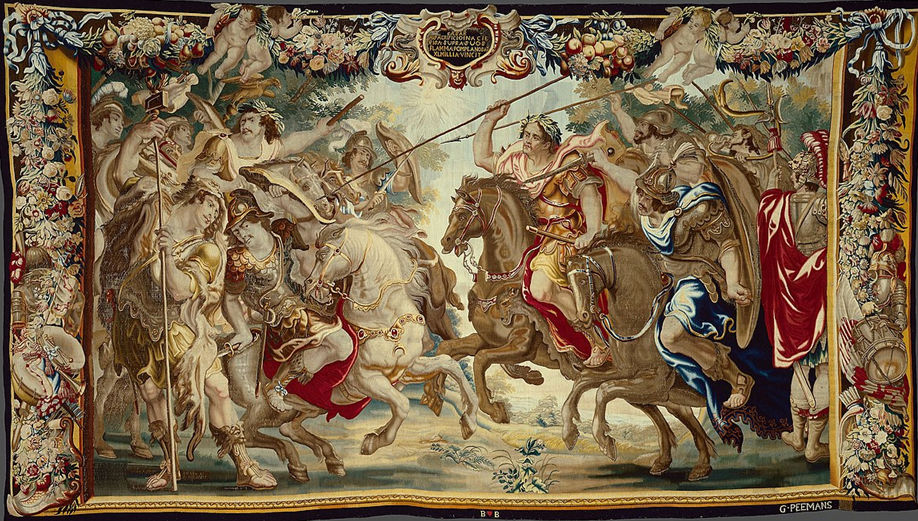

For five of the battle’s grueling nine months, I accompanied the Iraqi army. I was a minor participant of little consequence in the affair but one who nevertheless occupied a front-row seat to the Götterdämmerung. It was a consummate modern battle in every way, with tanks, smart bombs, and tablets used to plot coordinates for airstrikes. Beneath the thin veneer of modernity, though, the battle would have been perfectly comprehensible to any Roman or Greek.

The visceral experience for both besieger and besieged has not materially changed in 3,000 years: the privation, the randomness of death, massacres, looting, and bloody score-settling as one regime yields to another. We may use more sophisticated language in the employment of violence than our ancestors did, but the bureaucratization of organized killing with its euphemisms of “precision strikes”, “proportionality”, and “harm reduction” tends to obfuscate more than it clarifies. Modern warfare is merely the imprecise incineration of one’s foes by means of mechanical dragons and automated Furies.

I returned to the U.S. that summer shortly before Mosul was declared liberated, and I was immediately struck by the abrupt change in my surroundings. Just a few weeks earlier, I had been living in squalid conditions awash in horror and suffering. Now, I was attending a new student orientation at a university where I would soon be undertaking coursework in Arabic. The over-caffeinated speakers on stage led the incoming students and parents alike in singing a college pep cheer with accompanying dance moves. I felt an urgent need to leave and hurriedly made for the exit to take a walk across the tranquil campus.

The most disorienting thing about returning home from war in the modern age is its utter banality. There are no months of decompression marching back to one’s homeland with comrades or long voyages across the ocean to provide time for reflection. I was not forced to endure years of exile or adventure on the high seas in the time between leaving Mosul and sleeping in my own bed again. Regrettably, no goddess detained me during a layover with offers of immortality. I simply boarded a flight and was back in my familiar hometown the next day.

There, I found no parasitic suitors devouring my estate or conspirators plotting my demise. However unwelcome such things might have been, they at least would have offered the possibility of escape from the new monotony, and perhaps even some excitement. The transition was startlingly abrupt; one day, life was precarious and violent and the next, one was thrust back into the humdrum of peacetime life, listening as a customer complained about their botched latte at Starbucks.

Far from being circumspect about what I had experienced, I was quite eager to share some of the strange and bewildering vignettes from that surreal period of life with friends and family. The crucible of Mosul had engendered in me all sorts of incipient, conflicting views about religion, fate, and human nature. I was disappointed though to find few acquaintances who were interested in my ramblings. For most people, Mosul was an obscure place and the belligerents equally so. Unless one had a masochistic interest in following the course of spasmodic, violent conflicts in the Middle East, most were entirely unaware that something called the Battle of Mosul had occurred at all.

Friends and comrades whom I had served with would have understood, but they were either back in Iraq or scattered around the world like the victorious Argives after Troy. I quickly realized that what had been an all-consuming experience for me – undeniably the most formative of my adult life – was an event whose outcome made no appreciable difference to anyone back home.

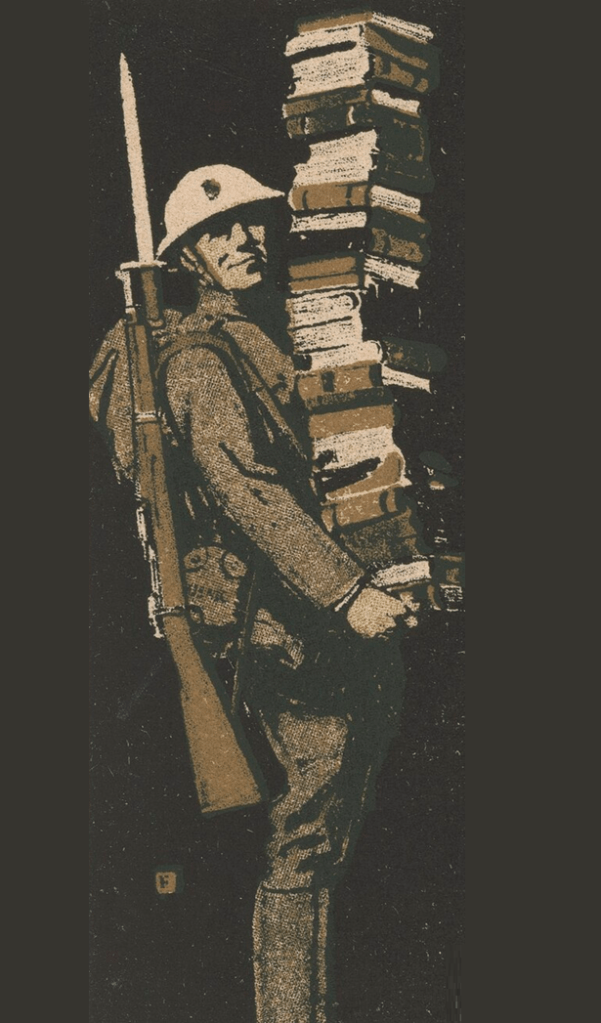

Faced with this frustrating reality, I found an unlikely refuge and source of comfort in literature, though not just any literature. Modern writing on the psychology of combat held little appeal, what with its sterile, clinical treatment of the subject matter and tendency to pathologize everything. I had little interest in looking under the hood of my own brain or ruminating on a couch. What I was really craving was good storytelling, and it was that desire that drew me inexorably into the Classics.

When I look back, some of my most cherished memories of Mosul were those nights spent listening to old, Iraqi soldiers talk about their lives and wartime experiences. Regardless of how faithful or embellished the accounts were, their universal themes of heroism and triumph in the face of adversity were instantly recognizable, transcending our different cultures. Storytelling is as old as humanity, and perhaps it is what made us human in the first place. If – as I was beginning to believe – the human experience could only be fully understood through stories, then what insights might some of history’s oldest and most enduring storytellers have to offer to a modern like me?

I had always enjoyed the romance of the Spartans, Alexander the Great, and Julius Caesar. My knowledge of Antiquity mostly derived from films such as 300 and Gladiator, from reading a handful of secondary sources in college, and from being an avid player of Rome: Total War as a teenager. Now, though, I felt compelled to go directly to the source material and see if I might find consolation in the musings and imaginations of the Ancient poets, bards, and historians. The Classic held more appeal than even the best novels, films, or music. I reasoned that the thousands of years separating us from the authors whose cultural assumptions were so alien to our own would only serve to make their timeless wisdom stand out more.

By fits and starts, I gradually dipped my toes into the imposing waters of the Classics. My new literary undertaking was a self-directed one unrelated to my graduate studies at the time. I acquired most of the books secondhand – I was especially fond of Robert Fagles’ translations – and thumbed through the pages on the bus and between classes without the aid of a teacher or accompanying commentary. Homer was the obvious place to start, with his epic treatment of war and troubled homecoming.

If I had been pressed to answer at the time, I would have struggled to say what precisely I was seeking in the Iliad and Odyssey beyond simple entertainment. For all its excitement, my own wartime experience had left me with a lingering, slightly discomfiting perspective – a bleak outlook on the human condition borne of the depravity, nihilistic violence, and seemingly purposeless suffering that had characterized the battle. Perhaps I felt that I lacked the intellectual tools or vocabulary to put these inchoate thoughts into words.

Homer began to give form to my impressions. His characters were instantly recognizable to me, variously motivated by glory, greed, or piety no less than the soldiers and religious fanatics I had encountered on the plains of Nineveh. They felt less like stock characters and archetypes than they did amalgams of the real, flesh-and-blood men I had met. Hector embraced his newborn son between the fighting as lovingly as the Iraqi soldier I knew who had welcomed a daughter into the world just days before his near-mortal wounding in battle.

Detail of a red-figure column-krater attributed to the Painter of York, 380-360 BC, (National Archaeological Museum, Ruvo di Puglia, Italy).

My fearless leader in Mosul had possessed all the reckless courage and prowess of Ajax. Like Achilles after the death of Patroclus, I had wept – albeit less murderously – when a dear friend was slain in the final weeks of the conflagration. When Homer described the son of Peleus strumming his lyre, singing the famous deeds of fighting heroes, it called to mind those many cold nights gathered around the kerosene stove in Mosul, listening as old veterans shared their stories of wars past.

It was true that Homer’s world was saturated with religion and the supernatural, but had my war really been so different? The vast majority of the belligerents assembled on the banks of the Tigris that spring understood the conflict in religious terms, and they constantly invoked the Almighty and sought His intercession. Divine favor in the great contest was no less indispensable to them than it had been for the Achaeans and Trojans.

My interest piqued by Homer, I proceeded to Virgil’s Aeneid and then Lucan’s Civil War with its haunting, vivid depictions of violence. I was astonished by one particular verse in the Neronian poet’s epic about the war between Pompey and Caesar:

sunt nobis nulla profecto

numina: cum caeco rapiantur saecula casu,

mentimur regnare Iouem. spectabit ab alto

aethere Thessalicas, teneat cum fulmina, caedes?

… mortalia nulli

sunt curata deo.

In fact there are no powers

over us; blind chance ravages the centuries;

we say “Jove reigns,” we’re lying. Would he behold

Thessaly’s bloodbaths from high heaven and still

hold back his lightning bolts?

… No god has ever cared for mortal affairs.

(Bellum Civile 7.445–8, 454–5, tr. M. Fox)

In an Iraqi field hospital filled with the screams of wounded and dying civilians, I had once despaired, indulging my own blasphemous impression that the gods on high were at best indifferent or at the very least complicit in the madness – if they even ruled at all. I was not then religiously inclined as I am now, but years removed from that moment and over 2,000 years after the bloody Battle of Pharsalus, I had discovered a Roman poet expressing a nearly identical sentiment to my own, and with far greater eloquence.

Epic poetry served as a gateway to the broader literature of Ancient Greece and Rome. I was enchanted by Herodotus’ world-building in setting the stage for the Persian Wars. Thucydides’ worklived up to its boastful prediction as a “possession for all time” (ktēma es aei) with his profound meditations on human nature and man’s capacity for violence. I could not have devised a more fitting eulogy for the soldiers I knew who had perished in the battle than that found in Pericles’ funeral oration (2.35–46), memorializing his fallen countrymen – those men who in a small moment of time, the climax of their lives, a culmination of glory, not of fear, were swept away from us (δι᾽ ἐλαχίστου καιροῦ τύχης ἅμα ἀκμῇ τῆς δόξης μᾶλλον ἢ τοῦ δέους ἀπηλλάγησαν., 2.42.4).

What began as the dabbling of a literary dilettante eventually turned into a habit of daily reading, still rigorously practiced to this day. Soon my bookshelves were overflowing with the writings of Plutarch, Cicero, Polybius, Athenian playwrights, and even guides for teaching myself rudimentary Greek and Latin. After a while, I became cognizant of a subtle theme that permeated most of the great epics and biographies – that the protagonists seemed to have unmistakably enjoyed themselves in the moment, whatever their trials or ultimate fate. They were conscious at some level of being actors in the sweeping epic of human history.

The observation went a long way in allaying a somewhat guilty, rarely-expressed sentiment of mine – that I too had strangely enjoyed the experience of war and being part of something grand and epochal. It was an enjoyment borne not of sadism or bloody-mindedness, but rather of an appreciation of the experience’s profundity and its limitless capacity to fascinate and to educate me about the world and its creatures.

Why then did the Classics themselves so affect me and why couldn’t a survey of modern, quality scholarship about antiquity have yielded similar results? I think part of the answer lies in the sheer vastness of time that separates us from the ancients. There is something sublime about encountering ideas, feelings, and thoughts across the millennia, to realizing that our circumstances are never unprecedented, that our thoughts are less original than we suppose, that the human condition is as timeless as it is universal, and that there is nothing new under the sun (or, as Ecclesiastes put it, nihil sub sole novum!).

Stories that have withstood the test of time provide us a framework for conceptualizing or reimagining our own experiences in life. Like culture, they help us make sense of events that would otherwise be meaningless and chaotic. The terror of the strange and gruesome is dissipated when it is recast as something familiar and recognizable. And so it was in the ancient court of literature each night that I dined and drank with royalty. Just as Dante was guided through Hell by Virgil, so too I navigated my own memories of that ghastly time not alone but in the company of the giants who had contemplated the same crooked timber of humanity that I had under the desert skies.

On the blackest days of the battle, I would often ironically comfort myself in the manner of Voltaire’s Candide that I was living in the best of all possible worlds. What was tongue-in-cheek then feels – with the benefit of hindsight – much closer to reality than it did at the time. It is one of life’s curiosities that experiences which are loathsome in the moment may be recalled nostalgically long after the fact. So it proved with the many strange and unholy sights, smells, and sounds of Mosul. It lends credence to the observation of another lover of the Classics who reminded us – via Hamlet – that there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

Perhaps this helps explain why, years later, I find myself occasionally waxing nostalgic for those halcyon, bygone days along the Tigris – those days of danger, camaraderie, madness, and human sacrifice. I would never have suspected back then that such an experience would open the door to a lifelong love of antiquity’s boundless riches and wisdom. Having survived the otherworldly destruction of Nineveh, the words of consolation offered by Aeneas to his comrades upon escaping their native Troy would have been no less reassuring to me: A joy it will be one day, perhaps, to remember even this (forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit, Aeneid 1.203).

Bradley Brincka is an Arabic linguist, ethnographer, and U.S. Army Reservist based in Oklahoma. His writing has appeared in Tablet Magazine, 1001 Iraqi Thoughts, and The Fireside Journal.