Politian

Translated by Jaspreet Singh Boparai

For an introduction to this remarkable lecture, and to the process of producing the first English translation of it, please read this companion article.

Oratio super Quintiliano et Statii Sylvis

Oration on Quintilian and Statius’ Silvae

Antequam ea dicere exordiar, iuvenes, quae suscepti a nobis operis propria esse videntur, rationem vobis totius consilii mei paucis explicabo. Non enim sum nescius fore aliquos quibus meum non satis iudicium probetur, quod ex tanto optimorum probatissimorumque numero voluminum Statii potissimum Sylvas Quintilianique Oratororias institutiones enarrandas susceperim: quorum alteras ne poetae quidem ipsi satis editione dignas dicant existimatas, alteras autem, etsi maxime accuratae eruditissimaeque videri possunt, Ciceronis tamen eodem in genere scriptis non fuisse anteferendas.

Gentlemen: before I begin to say anything suitable for the task I have undertaken, I shall explain the plan of my intended programme for you in a few words, since I am by no means unconscious that there will be some people for whom my power of judgement seems inadequately tested by experience, on the grounds that I have taken it upon myself to lecture on the Sylvae of Statius and the Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian, out of any number of valued and estimable books. Of these two, not even the poets declare the former to be worthy of publication; whereas the latter, even if it can be seen as a work of formidable and thorough accomplishment, nonetheless should not have been chosen over Cicero’s treatises on the same subject.

Ad haec neque satis a nobis nostrum fieri officium iudicent, qui haec ingenii tenuitate, hac doctrinae paupertate, hac tam exigua atque adeo nulla dicendi exercitatione cum simus, novas tamen quasique intactas vias ingrediamur, veteres tritasque relinquamus; neque autem discentium consulere utilitati, qui eis maxime senibus scriptores praelegamus, quo iam Romanae nobilitas eloquentiae et quaedam quasi ingenuitas degeneraverat, multoque nos profecto fuisse rectius facturos, si Vergilium Ciceronemque ipsos, Latinae facundiae principes, exponere essemus aggressi.

On top of that, they will think me unequal to my duties because, despite my modest ability, my want of learning, and an experience of public speaking so slight as to be negligible, I am nevertheless embarking on a novel, virtually unattempted course, leaving behind familiar ones of long standing. They will further conclude that I failed to consider the interests of my pupils, if I preferred any writers to the most ancient ones, after whom the excellence of Roman rhetoric declined, while a particular quality like the high-mindedness of the well-bred also diminished. Without doubt, I should have done far better, had I set out to lecture on Vergil and Cicero, the foremost masters of Latin eloquence.

His itaque cogitationibus rumoribusque hominum non malorum fortasse, nostri vero etiam amantium, paucis occurrendum esse existimo. Quod igitur ad Statium attinet, ut non hos satis esse absolutos libros paulisper dederimus, nihilo tamen secius cur eos praelegendos susceperimus egregie nobis ratio constiterit. Quid enim prohibet vel ideo adolescentibus non statim summos illos, sed hos si ita placet inferioris quasique secundae notae auctores ediscendos praebere, ut imitari illos facilius possint?

In light of all this, I suppose I ought to respond briefly to these conclusions and whisperings from men who surely mean no harm, and in fact are also my friends. Now then: as far as Statius is concerned, the judgement would be wholly correct that I have chosen for the time being to offer my pupils books which have been inadequately perfected, yet have undertaken to lecture on them anyway, because how does it hold back the young to present them initially, not with the greatest writers, but with those of – pardon the expression – lesser, supposedly inferior quality, to be learned by heart, so that they might follow their example with greater ease?

Nam quemadmodum novellis vitibus humiliora primum adminicula atque pedamenta agricolae adiungunt, quibus se gradatim claviculis illis suis quasique manibus attollentes in summa tandem iuga evadant, ita nec statim ad ipsos sicuti primi ordinis scriptores vocandi adolescentes, sed humilioribus iis, qui tamen haud abiecti humi iacentesque sint, quasi paulatim invitandi sublevandique videntur. Itaque neque qui aurigari discunt valentissimas statim ac praeferoces ad currum quadrigas adhibent, nec qui navali erudiuntur praelio non in portu prius tranquilloque mari aliquandiu exercentur, neque non multo facilius multoque libentius adolescentuli in scholis doctiores condiscipulos quam magistros ipsos imitantur; non enim cuiquam temere evadere ad summas licuerit, nisi proxima quaeque antea, nisi quae paratissima amplectatur.

Just as cultivators initially bind their young, newly-planted vines to stakes and support-palings which are relatively close to the ground, by which the vines might raise themselves on their tendrils, little by little, as if with their hands, and at last ascend to the tops of the cross-beams; in a similar manner, minors ought not to be summoned immediately into the presence of first-rate writers (so to speak). Instead, it seems they ought to be attracted, and encouraged gradually, by less significant writers – ones who are, of course, by no means worthless, vulgar, or despicable. Likewise, none who learn how to drive chariots will immediately bring the strongest, fiercest team of four to the car; nor do those who are taught naval warfare avoid practising at first in the harbour or over calm seas for any length of time; nor do young men in the classroom follow the example of their more experienced classmates with any less ease or willingness than they do the teachers themselves. The reason is that no man can climb casually to summits, unless he has first tried the closest, most convenient peaks around him.

Adde huc quod, qui primos illos vobis explicatum ierint, abunde semper habuistis; ad eos qui se demittere non recusarint, nullius vobis, quantum videam, ad hanc usque diem copia extitit, ut vel hoc ipso nomine magna illis habenda sit gratia, qui dum vestris consulant utilitatibus, quid de se quisque opinetur haud in magno ponunt discrimine.

Beyond all this, you have always had an ample supply of men who seek to interpret the most important writers for you. As for those authors to whom they decline to condescend, you have hitherto had, as far as I can tell, no such glut of them. For this very reason you ought to be grateful to anyone who, whilst looking out for your interests, places little importance on what others might think of him.

Quamquam in hoc quidem de quo agimus Statio, longe mihi ab iis quae dicta sunt aliena mens fuerit. Ut enim non ierim inficias, posse aliquid in tanta Latinorum suppellectile inveniri, quod his libellis vel argumenti pondere, vel mole ipsa rerum, vel orationis perpetuitate facile antecellat, ita illud meo quasi iure posse videor obtinere eiusmodi esse hos libellos, quibus vel granditate heroica, vel argumentorum multiplicitate, vel dicendi vario artificio, vel locorum, fabularum, historiarum consuetudinumque notitia, vel doctrina adeo quadam remota litterisque abstrusioribus nihil ex omni Latinorum poetarum copia antetuleris.

Although I am currently discussing Statius, what other people say about him is furthest from my mind. On that account, lest I deny that anybody could find any useful material among so many Latin authors that could easily surpass these books in the consequence of their subject matter, or the importance of the material being treated, or the consistency of style, it almost seems a duty for me to be able to maintain that these works are of such a standard that you would prefer nothing to them out of the entire force of Latin poets, be it for epic sublimity, or the multifaceted quality of their contents, or the artful diversity of expression, or the fame of their topics, or their fictional or historical narratives; or else for particular linguistic usages, or some suitably exotic erudition, in relatively rare scholarship.

Atque id ita evenire usu necesse fuit, quod cum singulae ipsae quae Sylvae inscribuntur singula a se invicem disiuncta argumenta continerent, earumque fines haud ita multos intra versus includerentur, nihil profecto sibi reliqui facere ad industriam circumspectionemque poeta debuit, cum et tantae rerum de quibus ageretur varietati respondendum videret, et haud longo in opere somnum obrepere sibi nefas existimaret.

And it has inevitably happened that, although the poems entitled the Sylvae, when taken by themselves, comprise various individual themes in turn, and are self-contained; and although their intended objects are by no means confined within their numerous lines; all the same, the poet was in no way bound to leave any material behind for further painstaking labour, even if he was aware of anything else reflecting that diverse mass of subjects he was treating, since he thought it shameful if he were to let sleep creep up on his readers in a short work.[1]

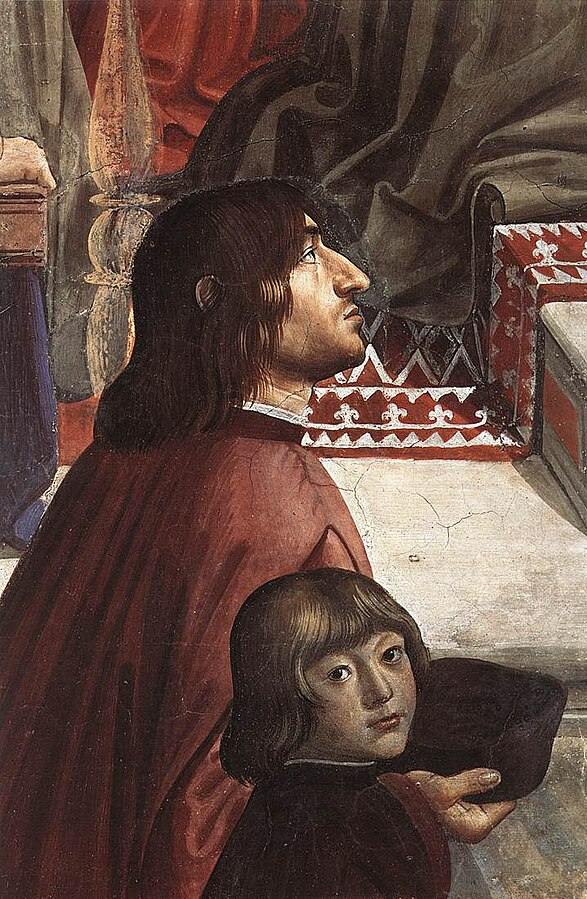

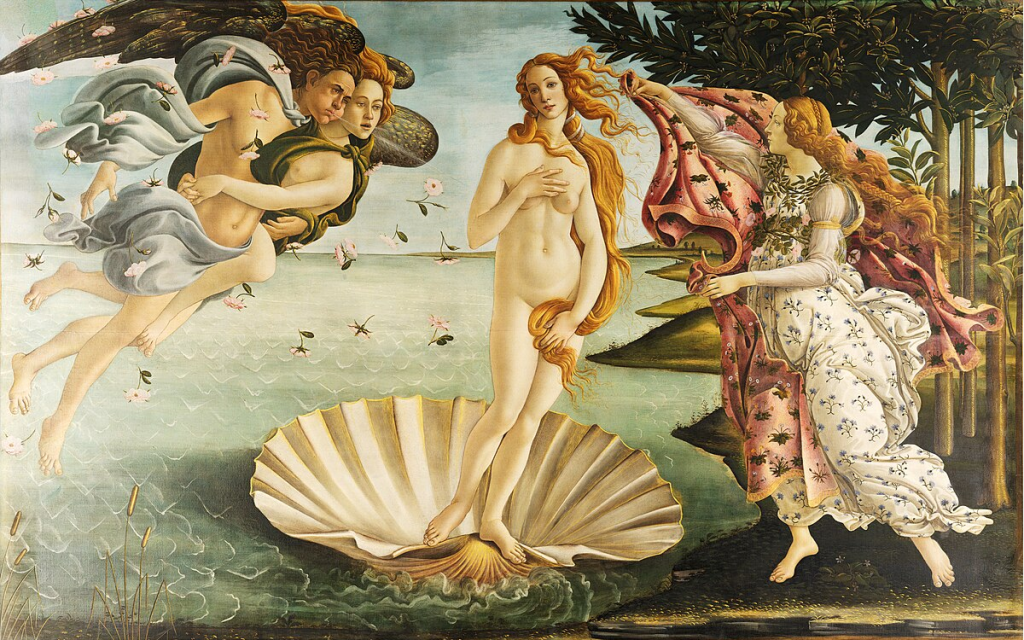

Itaque ut omnem facillime culpam praestari ab eo intelligas, nihil in illis non sagacissime inventum, non prudentissime dispositum est, nullus non tentatus locus atque excussus, unde aliqua modo voluptas eliceretur. Elocutionis autem ornamenta atque lumina tot tantaque exposuit, ita sententiis popularis, verbis nitidus, figuris iucundus, tralationibus magnificus, grandis resonansque carminibus esse studuit, ut omnia illi facta compositaque ad pompam, omnia ad celebritatem comparata videantur; tantumque abfuit quominus tam multiplici materiae omnibus locis suffecerit, ut eam quoque quasi Phidias aliquis aut Apelles insigni operis artificio superaverit.

For this reason, in order for you to understand how such a defect was entirely obvious to him, nothing in these poems has been guilelessly contrived, or artlessly arranged; there is no topic from which some pleasure might be derived that has been perfunctorily handled or investigated. On the contrary, he has displayed so many expressive figures and embellishments throughout; he has laboured to be so pleasing in his opinions, refined in his diction, appealing in his rhetoric, lofty in his metaphors, and grand and full of echoes in his poems that everything in them seems artfully arranged for display and fashioned to earn renown; and in all passages of his work, he was so far from being merely adequate for such many-sided subject matter that, like some Phidias or Apelles, he overcame it, thanks to his remarkable artistic skill.

Itaque ut in Thebaide atque Achilleide secundum sibi inter eius ordinis poetas suo quasi iure locum vindicaret, ita in his Sylvarum poematis, in quibus citra aemulum floruerit, tam sese ipse, ut meum est iudicium, post se reliquit, quam eundem Vergilius Maro in superioribus antecesserat. Atque huic nostrae de his libellis sententiae cum omnes docti viri siqui modo illos attigerunt, facile suffragabuntur, tum vos, ut spero, ipsi cum totos penitusque inspexeritis sine ulla controversia assentiemini. Quod siquis nunc forte a me ita quaerat: “cur igitur si tam nihil in his Sylvis desiderandum arbitraris, ipse illas tamen suus auctor vix quae in publicum edererentur dignas existimavit?” hunc ego contra sic rogabo: “cur autem tandem ediderit, si minus probabat?” Neque enim tam quid quisque cogitarit, quam quid tandem senserit, quid decreverit, quid denique effecerit, perpendendum est.

Thus, just as he laid claim, as if by right, to the second place among poets of his rank in his Thebaid and Achilleid, likewise in the poems of the Sylvae, in which he flourished without rival (as it seems to me), he surpassed himself by just as much as Vergil surpassed him in those earlier epics of his. As all men of learning – all who have come across these books, to be sure – will undoubtedly support my opinion on them, similarly you will all, I hope, agree with me without dispute, once you have fully digested them. If any of you should choose to ask: “Why do you so firmly believe there to be nothing missing in the Silvae, when the author himself thought them scarcely worthy of being brought before the public?”[2] I shall question him in turn: “But why should he have published them in the end, if he were less than satisfied with them?” Because one ought to consider, not so much what a man plans, as what as what he eventually realises, what he determines, and what he brings to pass in the end.

Itaque dum se “diu multumque dubitasse” ait, an eos libellos de integro collectos emitteret, facile ad id viam sternit quo sibi perveniendum destinaverat, ut tumultuaria scilicet esse illos “subitoque calore” effusos persuaderet. Quamlibet enim multis neque fucosis ornamentis abundarent, minime tamen homini de omni sua existimatione sollicito vel haec ipsa celeritatis commendatio fuerat negligenda, quippe cui et indulgentia liberior et venia proclivior et admiratio maior deberetur. Neque non tamen quam maxime emendatos esse vel inde colligimus, quod non temere ipsos neque inconsulto, sed post longam demum consultationem quasique subducta prorsus ratione edendos censuerit.

Wherefore, whilst Statius claimed he ‘deliberated long and hard’ about whether he ought to release that collection of poetry he had just assembled, all the while he was smoothly levelling a path towards an end he had already chosen for himself, with the effect that he consciously claimed those works to have been arranged in a hurry – those poems he supposedly poured out ‘in a sudden heat of inspiration’. Because however much they overflow with profuse rhetorical ornaments – which are not spurious – one should by no means overlook that that this very speed of composition was hardly to be thought praiseworthy in a man so anxious about his general reputation, inasmuch as he deserved freer indulgence for such a thing, and readier pardon, and even greater admiration. Yet the books we have since collected are nothing if not thoroughly corrected, because he concluded, not casually or rashly, but in fact after long meditation – or, in a word, calculation – that they ought to be published.

At videbat, inquies, ipse profecto nonnihil in his de expolitione desideratum iri, itaque quasi suae conscius imbecillae causae, velut petita ultro venia sese praemuniit. Hoc si nos maxime concesserimus, nihilo tamen secius posse hos esse vel quam emendatissimos pervicerimus. Itaque enim plerique ingenio sumus, non tam quid operis effecerimus, quam quanti nobis opera steterit ponderamus. Quapropter saepe evenit, sive id morositate quadam ingenii, sive iudicii nimia severitate, atque adeo tristissima censura, ut nihil interim absolutum putemus nisi in quo vehementissime laboratum sit.

But, you say, he surely noticed how he was not going to have a suitable degree of finish in these poems; and so, seemingly aware of his feeble excuse, he pre-empted objections as though he were seeking pardon from himself. If I concede this in particular, then I shall have carried the point that these poems must be in the most correct state attainable. Indeed, most of us are likewise inclined to weigh up, not so much the degree to which we may accomplish a task, as the amount of work left for us to complete. On this account it often turns out, either by a somewhat pedantic turn of mind, or else overly strict judgement, that we sometimes think something unfinished unless it has been worked at with strenuous effort.

Contra vero saepe usu venit ut scripta nostra nimia cura vel peiora fiant, neque tam lima poliantur quam exterantur. Atque hoc nimirum excellentissimus pictor Apelles significabit, cum a se una in re Protogenem superari diceret, quod ipse manum de tabula sciret tollere. Hinc contra statuarius Callimachus Cacizotechnos meruit appellari, quod semper et ipse calumniaretur neque diligentiae finem haberet.

On the other hand, it often happens that our writings are produced with excessive or burdensome attention, so that they are worn away with a file, rather than merely polished. Doubtless the highly distinguished painter Apelles meant this when he claimed that Protogenes surpassed him in one thing, to wit, that he knew when to take his hand away from the canvas. Conversely, the sculptor Callimachus Cacizotechnus deserved the name because he was too careful, nor could he bring his scrupulous attention to some appropriate limit.[3]

Itaque cum emendata eius essent opera, gratiam tamen iis omnem diligentia abstulerat. Hoc ipsum et Suetonius in Tiberio indicat, quem “morositate ait stilum obscurare solitum”. Nocet enim profecto saepe nimia diligentia. Et ut cultus concessus atque magnificus addit auctoritatem, ita accersitus ille atque fucatus bonam ipsam virtutem lenocinio contaminat.

Likewise, although Statius’ works have been corrected, all the same he has sometimes robbed them of charm by overworking them. Suetonius mentions the same defect in his life of Tiberius who, he says, tended to muddy his manner of expression with pedantic subtlety;(Cf. Suetonius, Tiberius 70: “Artes liberales utriusque generis studiosissime coluit. In oratione Latina secutus est Corvinum Messalam, quem senem adulescens observarat. Sed adfectatione et morositate nimia obscurabat stilum, ut aliquanto ex tempore quam a cura praestantior haberetur.”)) for it is true that too much effort often does harm, and just as a splendid refinement applied to a work augments its prestige, in the same way a far-fetched and unnatural surface polish pollutes that same honest value with vulgar artificiality.

Quod siquis tamen pertinacius illud obtinere velit, imitatione indignas esse has Papinii Sylvas, quas paene ipse auctor improbaverit, idem pari ratione et Vergilii Aeneidem ne lectione quidem dignam atque igni etiam concremandam iudicare possit, quam summi homo elegantissimique iudicii eius auctor Vergilius Maro flammis abolendam caverit testamento. Nos tamen et Aeneidem in primis legimus, et Graecis illam praecipue Homeroque opponimus; et Statii Sylvas egregium atque in eo genere unicum opus, quodque auctori suo felicissime omnium successerit, non solum publice enarrandas, sed ediscendas etiam, et oratoribus aeque poetisque imitandas exprimendasque censemus. Ac de Statio quidem hactenus.

Nevertheless, anyone who too stubbornly wishes to demonstrate this might consider Papinius Statius’s Sylvae, which the author himself practically rejected, to be unworthy of copying; by the same logic he might think Vergil’s Aeneid unfit even for reading, and that it must be burnt, since its author Vergilius Maro, a man of profoundly discerning taste, took care in his will to ensure that it was destroyed by fire. Despite this we read the Aeneid before anything else, and compare it to the Greek masterworks, especially Homer’s. I consider Statius’s Silvae an outstanding work, unparalleled of its kind. It has enjoyed the happiest fortunes of all its author’s productions, and ought not merely to be the focus of public lectures, but also studied in schools, to be copied and imitated by poets and statesmen alike. So much for Statius, for the moment.

Quintilianum vero non nos quidem illum Ciceroni praetulerimus, sed has certe eius Oratorias institutiones rhetoricis Ciceronis libris pleniores uberioresque esse existimamus, nempe quae ab ipsa quasi infantia atque ipsis incunabulis instituendum oratorem susceperint, summamque eius eloquentiae manum imposuerint. Itaque ne ipse quidem Cicero satis quae de arte oratoria scripserit probasse omnia videtur. Nam et rhetoricos libellos in iis qui De oratore sint haud usquequaeque sequitur, et rudes inchoatosque adolescent sibi excidisse e manibus affirmat, et ab his ipsis De oratore in alio Ad Brutum libro identidem desciscit, neque in hoc quoque, quod extremum absolverit, ulla de parte praecepta ponit, sed oratorem quasi ipsum informat et quod dicendi sit optimum genus decernit.

I definitely do not prefer Quintilian to Cicero. All the same, I think his Oratoriae Institutiones to be fuller in treatment, and richer in material, than Cicero’s treatises on rhetoric which, to be sure, train up the budding public speaker beginning from infancy and swaddling-bands (as it were), and also give the finishing touch to his rhetorical skills.[4] Yet by the same token, not even Cicero himself seems to have been satisfied with everything he wrote on rhetorical technique. He in no way conforms uniformly in his De oratore to the standards of his own rhetorical manuals which, he confirms, fell from his hands in a raw, incomplete state. In a similar way he deviates from De oratore in his treatise Ad Brutum; nor does he lay down any rules on technique in this, which stands as his last word on the subject. Instead, he sketches a picture of a public speaker not unlike himself, and determines what his optimal manner of speaking might be.

Ergo et philosophi nostri non, cum in primis Aristotelem sequantur, statim illum Platoni anteponunt, ita nos quod Quintilianum quam Ciceronem interpretari maluimus, non quidem Ciceronis sacrosanctam illam gloriam detractavimus, sed ad Ciceronem festinantibus vobis egregie consuluimus. Haec igitur et de Quintiliano nostra ratio fuerit. Sed neque inusitatas vias indagamus, cum veterum libros auctorum in manus sumpserimus, qui tamen si minus in usum consuetudinemque hominum aliquot iam ante saeculis non venerunt, non tam ipsorum culpa quam fortunae ac temporum iniuria effectum est.

Therefore, just as our philosophers, although they principally model themselves on Aristotle, do not automatically prefer him to Plato, likewise when I have chosen to teach Quintilian rather than Cicero, I have by no means disparaged Cicero’s inviolable honour. Instead I have commendably thought about the best interests of you who are hurrying on your way towards Cicero. This, then, has been my plan with respect to Quintilian. But when we take the books of ancient authors into our hands, we are not embarking on an exploration of little-used pathways – even if these books are somewhat less in men’s everyday use at present than in times past – not so much through any fault of their own, as because of the damage inflicted by ill-luck and circumstance.

Quid enim nunc attinet superiorum calamitatem temporum memoria repetere? Quod sine summo dolore facere vix pie possumus, quibus insignes illi atque immortalitate dignissimi scriptores partim a barbaris caesi foedeque laniati sunt, partim ab his ipsis ad nostrorum usque parentum memoriam velut in carcerem coniecti atque in compedibus habiti, vix tamen aliquando, sicut erant semilaceri atque trunci multumque a seipsis immutati suam hanc in patriam reverterunt.

What need is there here to recollect the mishaps of bygone days? We can hardly do so properly without deep sorrow, when some prominent authors, as worthy as any of undying fame, were destroyed by ignorant foreigners and cruelly mangled; when other authors were hurled into dungeons and held in shackles, as it were, from the dark ages right up to our parents’ generation (and even our own), scarcely ever returning home unaltered from their previous state, virtually half-maimed, and badly dismembered.[5]

Perquam igitur inhumanum facinus a nobis fieret, si de nobis deque maioribus nostris optime meritos insignes hos viros dudum deposita capitis diminutione, iure postliminii civitatem repetentes, non vel quam libentissime agnoscamus atque in ipsam, quae his maxime debet Latinitatem, suam in rempublicam, suum in ordinem, atque adeo intra privatos parietes nostros, intra nostrum sinum benigne admiserimus. Quod quidem si me nunc primum auctore adipiscentur, cur mihi tandem id vitio vertatur, aut cur non summa potius gratia ab omnibus habeatur, quod quasi mea privata pecunia publicum omnium aes alienum dissolvere non dubitarim?

We would have perpetrated a viciously savage crime if we did not gladly recognise these noble men, eminently deserving (from ourselves as well as our ancestors) of a full restoration of their former status, when with complete justice they seek to reassert their right to return to their old condition and privileges; and we should readily welcome them back into their own country – which owes to them most of all its purity of Latin style – and into their proper rank. What is more, we ought to welcome them into our private homes, and into our embraces. Now if, with my sponsorship, they should attain this, then why would it be reckoned my fault – or rather, why should I not enjoy heartfelt universal thanks instead, because I have beyond doubt discharged a national debt with my own private means, so to speak?

Postremo ne illud quidem magni fecerim quod horum scriptorum saeculo corrupta iam fuisse eloquentia obiciatur, nam si rectius inspexerimus, non tam corruptam atque depravatam illam, quam dicendi mutatum genus intelligemus. Neque autem statim deterius dixerimus quod diversum sit. Maior certe cultus in secundis est, crebrior voluptas, multae sententiae, multi flores, nulli sensus tardi, nulla iners structura, omninoque non tantum sani quam et fortes sunt omnes et laeti et alacres et pleni sanguinis atque coloris. Quapropter ut plurima summis illis sine ulla controversia tribuerimus, ita priora in his aliqua multoque potiora existere iure contenderimus. Itaque cum maximum sit vitium unum tantum aliquem solumque imitari velle, haud ab re profecto facimus, si non minus hos nobis quam illos praeponimus, si quae ad nostrum usum faciunt undique elicimus stque, ut est apud Lucretium,

Floriferis ut apes in saltibus omnia libant,

omnia nos itidem depascimur aurea dicta.

Finally, I should grant no importance to the reproach that rhetoric had deteriorated in the time of these writers, because if we have observed matters more accurately, we understand, not so much that their expression is decayed and corrupt, as that the manner of speaking has changed. Moreover, we should not reflexively call something worse because it is different. Indeed, there is a greater refinement in the later writers, a more abundant pleasure: numerous pithy statements, many rhetorical flourishes; no dull ideas, no artless arrangements; they are everywhere not so much correct in their style as forceful, rich, lively – filled with brilliance and vigour. Therefore, in order to attribute so many qualities to these bodies of work without further quarrel, we must assert that we rightly judge certain elements in them to be superior, and indeed preferable. And so, although it is the gravest error for one to want to copy only a single model, surely we by no means act against our own interests if we prefer the later writers to our own productions, no less than the classic ones if, whenever we produce works for our own advantage, we conjure up authors from every part: as Lucretius says,

As bees in flowery woodland pastures taste of everything,

So we cull all manner of golden maxims.[6]

Atque hoc profecto est quod, cum diu Marcus Cicero Atticis illis limatis et emunctis oratoribus operam dedisset, post illa tamen et Rhodiis et Asiaticis oratoribus aures commodavit. Quorum lenti illi quidam atque remissi, ii vero inflati, vani atque iactantes, utrique vero minores Atticis quasique ab iis degenerantes existimarentur. Itaque egregie nobilis pictor, qui cum interrogaretur quonam in primis magistro profecisset: illo, inquit, populum intuens; et recte id quidem. Nam cum nihil in natura hominum sit ab omni parte beatum, plurium bona ante oculos ponenda, ut aliud ex alio haereat et quod cuique conveniat aptandum est.

This is definitely why, when Cicero devoted his continued attention to those fine, discerning Attic rhetoricians, he still subsequently lent his ears to Rhodian and Asiatic public speakers.[7] Of these, the former were sluggish and drawling, the latter pompous, ostentatious, and vainglorious; both were considered inferior to the Greeks, as though they had deteriorated from that model.[8] In like vein, there was a particularly well-known painter who, when asked under which teacher he made the most progress, replied: ‘only this one: paying close attention to the public.’ How right he was. Since nothing in the character of men ‘is fortunate in every respect’,[9] serviceable qualities from the general public should be put before one’s eyes, so that one element might stick from one quarter, another from another, and whichever is suitable for each part is adapted for use.

Quare hoc idem et vobis persuasum velim, ingenui iuvenes, ut non iis tantum quae a nobis explicentur contenti alios item bonos auctores pertractetis et cum vos doctioribus mihique longe anteferendis dedideritis, mea tamen haec quae sedulo in medium afferuntur boni consulatis. Tales igitur nostri consilii causae extiterunt, in quo tamen capiendo magis plerisque vestrum, quibus ita cordi esse intellexerim, quam aut meo animo aut privatae persuasioni sum obsecutus. Nunc ad rem nostram aggrediamur.

On this account I should likewise hope to persuade you, worthy young men, that those of you who are not so keen on the writers on whom I shall be lecturing, will treat other great writers in the same way; and when you hand yourselves over to teachers who are more learned than I, and vastly to be preferred, you will nonetheless favourably judge these works which I have designedly made known to the public. The thinking behind my programme has now been made clear: by choosing such a scheme, I have accommodated myself to what I understood to be most agreeable to a majority of you, instead of gratifying my own sensibility or personal convictions. Now let us begin our task.

Nos quidem, cum poetam legere institueremus, ante omnia quod ad ipsam poeticen pertineret ea quae maxima in nobis fuerit diligentia enucleavimus. Idem hoc tempore de arte oratoria facere supersedebimus, cum quia nihil fere est, quod quidem ad rhetoricam ipsam requiratur, quin ab hoc quo de agitur Quintiliano vel praeclarissime explicatum sit; tum quod, si qua nobis praeterea succurrant, ea suum aliud in tempus suumque alium in locum aptius reservamus; quapropter iis quae maxime huius operis propria sunt contenti, intentionem primum, mox utilitatem horum exponemus librorum, tum pauca de auctore prosecuti ipsam quae princeps nobis occurrat epistola paucis interpretabimur.

I, for one, when undertaking to read a poet, try to get at the heart of the material demanding the closest attention, before anything else relevant to the art of poetry itself. Thus, on this occasion, I shall forgo dealing with the art of rhetoric, since there is scarcely anything pertinent to public speaking which is not set out with admirable thoroughness in the text by Quintilian with which I am about to engage; although if such material turns out to be relevant to our purposes after all, I shall save it for the appropriate point or context. Wherefore, I shall first set out the purpose, and presently the usefulness, of these books, for those who are keenest on that technical material peculiar to this work; then, having gone over the writer very briefly, I shall explain in a few words the letter which presents itself to the reader at the beginning of this treatise.

Est autem Quintiliano propositum oratorem eum instituere qualem fuisse neminem memoriae sit proditum, qui et moribus perfectus et omni scientia omnique dicendi facultate sit absolutus; quapropter qui tantae moli sit destinatus eum recens natum, quasi de matris gremio suum in sinum continuo accipit, nihilque sibi reliqui facit, quod quidem ad educandum, erudiendum informandumque illum pertinere intelligat, nunquam a se ante dimissurus quam cum vivendi, sciendi dicendique omnibus numeris perfectum atque absolutum, planeque oratorem summum singularemque reddiderit. Atque ad hunc unum terminum omnes, non suas modo, sed omnium ut quique probatissimi forent veterum scriptorum sententias, omniaque praecepta quasi sagittas in scopum rectissime collineat. Ac de intentione hactenus.

Quintilian proposed to train a public speaker who was like nobody thitherto recorded in history, exquisite in conduct, and without flaw in any expertise or expressive art. Because of this he more or less snatched his newborn son, whom he destined for such powers, from his mother’s breast into his own lap, and ensured that he overlooked nothing which he understood to be relevant to training, instructing, and moulding the boy. He would not let the lad go before he was exquisite and flawless in all aspects of conduct, expertise, and expression, or before he had made him into a peerless public speaker. To this single end he directs, not only his own advice, but the maxims and propositions of all the most eminent and respected ancient authors, like arrows aimed straight at a target. So much for the purpose of this book.

Utilitas autem tanta in his voluminibus existit, quantum vix fortasse in unis alterisve ex omni Graecorum Latinorumque copia inveneritis. Nam ut quod caput est ipsam tantummodo, qua de hic in primis agitur, rhetoricen inspiciamus. Quid est, quaeso, praestabilius quam in eo te unum vel maxime praestare hominibus, in quo homines ipsi ceteris animalibus antecellant? Quid admirabilius quam te in maxima hominum multitudine dicentem, ita in hominum pectora mentesque irrumpere, ut et voluntates impellas quo velis atque unde velis retrahas, et affectus omnes vel hos mitiores, vel concitatiores illos emodereris, et in hominum denique animis volentibus cupientibusque domineris?

Now, there is as great a profit in these volumes as you will rarely find in any work from the vast riches of Greek and Latin literature. Let us look more closely at the focus of this book, the art of oratory, with which it is principally concerned. What, I ask, is better than to excel other men in that very quality in which man himself stands above the rest of Creation? What inspires more awe than you do, speaking before a great crowd of men, so that you inspire their hearts and their minds, and thus direct their desires where you please, and likewise draw them back at will, and control all their moods, rendering them more placid, or else firing them up, so that, in short, you hold dominion over the minds, the wills and the desires, of man?

Quid vero praeclarius, quam praestantes virtute viros eorumque egregie res gestas exornare atque extollere dicendo, contraque improbos pernitiososque homines orandi viribus fundere ac profligare ipsorumque turpia facta vituperando prosternere atque proculcare? Quid autem tam utile tamque fructuosum est, quam quae tuae reipublicae carissimisque tibi hominibus utilia conducibiliaque inveneris, posse illa dicendo persuadere eosque ipsos a malis inutilibusque rationibus absterrere? Quid autem tam est necessarium quam loricam semper eloquentiae telumque tenere, quo et propugnare te ipse et incessere adversarium et circumventum a pessimis hominibus tuam innocentiam tueri possis?

Really, what is nobler than to praise and exalt with your words men of outstanding character, and the deeds they have performed uncommonly well, whilst your force of argument casts down dishonest and destructive men, and dashes them to the ground, and, through censure, lays low their shameful deeds, then tramples on them? Moreover, what is so beneficial and productive as to be able to convince people with your words about business you find advantageous and profitable, to your country, and to the men you love most dearly, whilst you frighten them away from wicked and injurious transactions? What is more indispensable than to maintain the perpetual cuirass and missile of rhetoric, with which you may defend yourself, and assail a rival, and protect your integrity, when it is beset by the worst knaves?

Quid autem tam munificum tamque bene institutis animis consentaneum, quam calamitosos consolari, sublevare afflictos, auxiliari supplicibus, amicitias clientelasque beneficio sibi adiungere atque retinere? Age vero ut nunquam forum, nunquam rostra, nunquam subsellia, nunquam conciones ineamus, quid tandem est in hoc ocio atque in hac privata vita iucundius, quid dulcius, quid humanitati accomodatius, quam eo sermonis genere uti, qui sententiis refertus, verbis ornatus, facetiis urbanitateque expolitus, nihil rude, nihil ineptum habeat atque agreste? In quo omnia comitate, omnia gravitate et suavitate condita sint? Haec igitur una res et dispersos primum homines in una moenia congregavit, et dissidentes inter se conciliavit, et legibus moribusque omnique denique humano cultu civilique coniunxit.

What is so generous, so suitable for well-brought-up men, as to comfort men who suffer, encourage the distressed, relieve one’s petitioners, and, through services join men to oneself in friendships and protection relationships, then maintain them by the same means? Come then, if we never enter the Forum, the Rostra, the tribunals, the public assemblies – what, at last, is more pleasing in one’s leisure hours and private life, what is more appropriate for men of good breeding, than to employ that manner of conversation which is replete with pithy expressions, set off with choice phrases, graced with elegant wit, and possessed of nothing clumsy, tasteless, or coarse? In which the whole is furnished with courtesy, dignity, and agreeable good manners? Accordingly, this very resource above all has gathered together diverse men under a single roof, and made adversaries friendly with one another; at last, it has united principles, customs, and all civilised polite society.

Quapropter etiam deinceps in omnibus bene constitutis beneque moratis civitatibus una omnium semper eloquentia effloruit summumque est fastigium consecuta. Quid ego nunc iam inde usque ab heroicis temporibus posita facundiae summa praemia, maximos oratoribus honores habitos, maxima commoda publicis rebus per homines eloquentissimos importata commemorem? Quae si iam singula, non dicam exornare dicendo, sed percensere coner enumerando, “ante diem clauso componet vesper Olympo.” Itaque ut quod sentio complectar brevi: nulla unquam profecto vitae pars, nullum tempus est, nulla fortuna, nullae aetates, nullae denique nationes, in quibus non cum maximas dignitates summosque honoris gradus facultas oratoria consecuta sit, tum non suis modo, sed privatorum quoque et plurimorum atque adeo universae civitatis rationibus plurimum contulerit.

Further, one form of rhetoric has continually prospered above all others, in every orderly, settled body politic, and attained the most exalted rank. Why need I mention how, ever since the heroic ages,[10] the greatest rewards have been offered for public speaking, the highest offices are held by good speakers, and the richest advantages for states arise through men who are the most powerful talkers? If I ventured – I shall not say, to deck them out with my words – but if I ventured to review all these benefits singly, listing them one by one, then ‘Olympus’s gates would sooner shut, and the evening star would put the day to rest’,[11] before I finished. And so I shall explain in a few words what I perceive: without doubt there has never been any stage in life, or period, or generation, or, finally, any race, in which rhetorical skill has not won the most distinguished reputations, and the highest ranks of public office, whilst it has been of maximal profit, not simply to personal affairs, but those of family, community, and the whole body politic.

Ad hanc igitur talem, tam praeclaram, tam egregiam possessionem Quintilianus hic noster expedita quadam quasique militari via vos perducet, iuvenes, in quam citato gradu agite, dum universi ingredimini, ut et decori vestro, et amicorum usui, et huius florentissimae reipublicae emolumento consulatis. Haec de utilitate; nunc de Quintiliani vita paucis absolvam.

Thus, young men, our Quintilian guides us towards such a considerable, remarkable, singular property, having revealed, as it were, a highway for us to march along, over which you must travel with hasty step whilst all of you proceed through, so that you may look out for your own glory, the interests of your friends, and the profit of this prospering commonwealth. So much for applications; now I shall briefly recount Quintilian’s life.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Cf. Horace, Ars Poetica 354–60: ut scriptor si peccat idem librarius usque / quamvis est monitus, venia caret, et citharoedus / ridetur, chorda qui semper oberrat eadem: / sic mihi, qui multum cessat, fit Choerilus ille, / quem bis terve bonum cum risu miror; et idem / indignor quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus, / verum operi longo fas est obrepere somnum. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Cf. Statius, introductory epistle to Sylvae 1: “Diu multumque dubitavi, Stella iuvenis optime et in studiis nostris eminentissime qua parte et voluisti, an hos libellos, qui mihi subito calore et quadam festinandi voluptate fluxerunt, cum singuli de sinu meo pro<fugissent: corr. Phillimore 1917>, congregatos ipse demitterim.” |

| ⇧3 | Cf. Pliny, Natural History 34.19. ‘Cacizotechnus’ is a Latinisation of the Greek κακιζότεχνος, which means ‘meticulous to the point of over-scrupulosity’. Someone which is described thus always finds fault with his own handiwork. |

| ⇧4 | Oratoriae Institutiones is merely another way of referring to the Institutio Oratoria. There is no need to read too much into these Renaissance conventions. |

| ⇧5 | Politian is surely alluding here to Poggio Bracciolini’s famous letter on the discovery of a Quintilian manuscript at St Gall, in which long-forgotten texts mouldering in libraries are described as though they were prisoners in a dungeon, shackled to the wall, suffering from neglect, and mutilated as a result of torture; see E. Garin (ed.), Prosatori latini del quattrocento (Milan, 1954) 240–6. |

| ⇧6 | Lucretius, De rerum natura 3.11–12. |

| ⇧7 | Cf. Cicero, Brutus 13.51: “At vero extra Graeciam magna dicendi studia fuerunt maximique huic laudi habiti honores illustre oratorum nomen reddiderunt. Nam ut semel e Piraeo eloquentia evecta est, omnes peragravit insulas atque ita peregrinata tota Asia est, ut se externis oblineret moribus omnemque illam salubritatem Atticae dictionis et quasi sanitatem perderet ac loqui paene disceret. Hinc Asiatici oratores non contemnendi quidem nec celeritate nec copia, sed parum pressi et nimis redundantes; Rhodi saniores et Atticorum similiores. Sed de Graecis hactenus; etenim haec forsitan fuerint non necessaria.” |

| ⇧8 | Cf. Ibid. 95.325–36: “Sed si quaerimus cur adulescens magis floruerit dicendo quam senior Hortensius, causas reperiemus verissimas duas. Primum, quod genus erat orationis Asiaticae adulescentiae magis concessam quam senectuti. Genera autem dictionis duae sunt, unum sententiosum et argutum, sententiis non tam gravibus et severis quam concinnis et venustis, qualis in historia Timaeus, in dicendo autem pueris nobis Hierocles Alabandeus, magis etiam Menecles frater eius fuit, quorum utriusque orationes sunt in primis ut Asiatico in genere laudabiles. Aliud autem genus est non tam sententiis frequentatum quam verbis volucre atque incitatum, quale est nunc Asia tota, nec flumine solum orationis, sed etiam exornato et faceto genere verborum, in quo fuit Aeschylus Cnidius et meus aequalis Milesius Aeschines. In his erat admirabilis orationis cursus, ornata sententiarum concinnitas non erat. Haec autem, ut dixi, genera dicendi aptiora sunt adulescentibus, in senibus gravitatem non habent.” |

| ⇧9 | Cf. Horace Odes 2.16.27–8: nihil est ab omni / parte beatum. |

| ⇧10 | Cf. Cicero, De divinatione ad M. Brutum, I.1.1: opinio iam usque ab heroicis ducta temporibus. |

| ⇧11 | A quotation from Vergil: cf. Aeneid 1.374–6: O dea, si prima repetens ab origine pergam / et vacet annalis nostrorum audire laborum, / ante diem clauso componet Vesper Olympo. |