Joel Moore

Everyone loves opposite day. Who doesn’t enjoy the idea of the world turning upside down for a brief time? This is a notion which has captured the popular imagination for centuries. It is a common childhood game to declare opposite day and perform actions which would usually involve breaking well-established rules, often to the detriment of others. In an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants, the characters SpongeBob and Patrick enjoy their own opposite day with hilarious results, such as talking backwards and damaging a house rather than repairing it (and if this prosaic description of a children’s television programme has not sold it, I do not know what will).

Opposite day is fun because it suspends the usual order of things. It invites the participant into a strange world where enjoyment emerges from incongruity with the day-to-day. If dancing on a table were normalised, it would be much the same as dancing on the floor. However, the fact that it is not usually allowed brings a certain excitement. The Roman people embraced this type of entertainment not only as a fun concept, but they transformed it into a series of codified religious events. These were so important that Roman thinkers did not just enjoy the experience of opposite days but they spent many hours studying them since the murky days of their distant histor. Praetextus says in Macrobius’ Saturnalia: quaesitu dignum omnes veteres putaverunt, “all the ancients thought [these days] worthy of study”).[1] The Romans enjoyed opposite days in the form of feriae and festi: holidays and festivals.

Before continuing, we must define the difference between these two terms. Feriae (plural in form but often singular in meaning) were holidays; these holy days could be public – arranged and paid for by the state – or private, observed by individuals and families. Public celebrations could be found in three different forms: feriae stativae, fixed holidays, which were part of the official calendar (just as Christmas always appears on 25 December); feriae conceptivae, movable holidays, which were set by public or religious officials (in a similar way to how Easter moves around each year); and feriae imperativae, holidays on demand, which were ad hoc ‘celebrations’ that could be called in response to a disaster in order to appease the gods (the historian H.H. Scullard suggested that these tended to be less cheery occasions – and you can imagine why).

Private feriae included events such as funerals and birthdays; they had a religious element but were limited to a smaller group of individuals and not the entire city. Festi were, quite simply, days off work. The Romans held ludi, games, on dies festi, festival days.[2] One might compare ludi to the various fairs and theatre festivals which still show up in towns across modern-day nations. On these occasions, Romans were able to enjoy time off from their day-to-day labours with supplied entertainment.

We can see the spirit of opposite day not only in Roman festivals but contemporary ones too. Consider Christmas celebrations, where families and friends often gather for a day of gift-giving and companionship. This is a special occasion precisely because it suspends the usual order of things: it is a day set aside to be different. Some of my fondest memories of university on the sunny shores of St Andrews involved an annual two-day celebration of traditionalised revelry called Raisin Weekend.[3] Raisin Sunday starts early in the morning with house parties, takes to the streets in the afternoon with a list of various fun challenges and concludes with yet more house parties. Monday sees the first years dress up in costumes and then proceed to a foam fight on the lawn of an ancient college building. The occasion is always out of the ordinary and, for want of a better word, weird. If it occurred every day, it would not be anywhere near as enjoyable or memorable.

There are myriad examples, from brief market town May Fairs with carnival rides and games to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, where performers take to stages large and small to delight visitors and annoy locals for an entire month. Festivals and holidays of all kinds have emerged all across the world, from China to Canada, Sweden to South Africa, and beyond. All of these settings embrace the extraordinary characteristic of being an opposite day, and it was much the same in Ancient Rome.

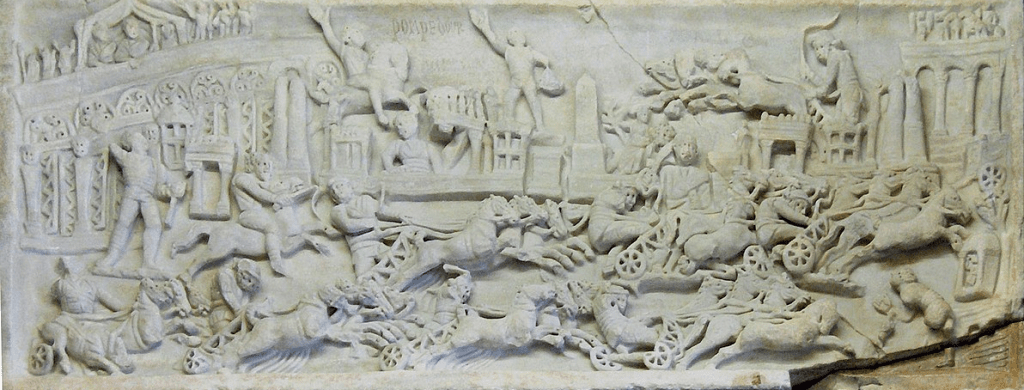

Roman festivals were large and frequent affairs. With several held each month, and crowds gathering across the city, they were impossible to miss. The Ludi Apollinares, games held in honour of Apollo in July, lasted eight days, and the Ludi Romani, a large civic festival taking place in September, went on for sixteen days by the time of Julius Caesar’s death in 44 BC!

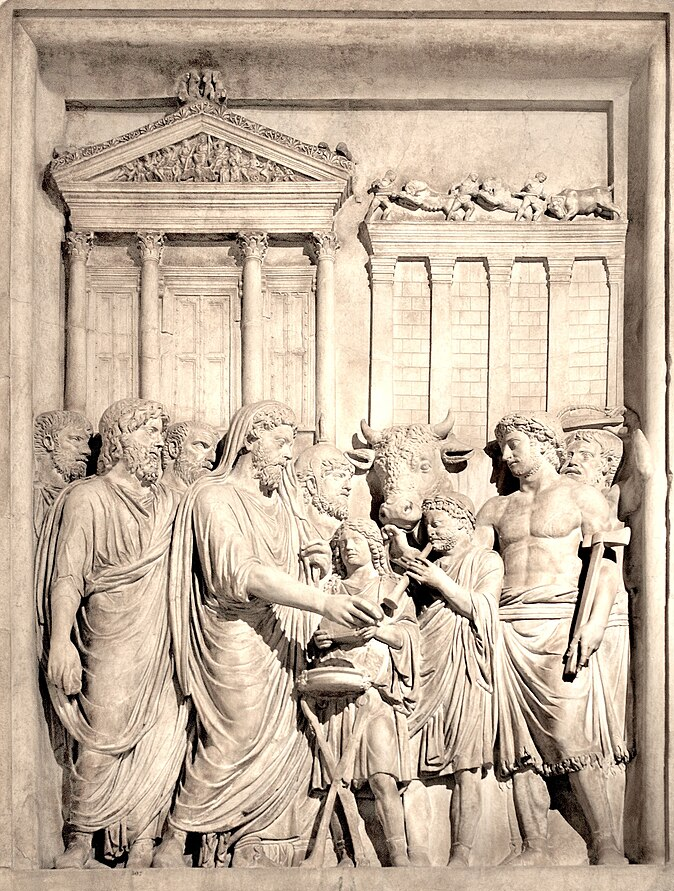

There were varied spectacles to keep the attendees’ interest. The Ludi Romani opened with a grand procession followed by days for chariot racing, called ludi circenses, and days for theatre, ludi scaenici, which were all provided free of charge to anyone who wished to attend. For a few days, Rome was transformed into a place of enjoyment and games. Shops, law-courts and schools were shut.[4] There was a spirit of opposite day across the city, as the normal order disappeared. In fact, it was religiously mandated that Romans were not to work on feriae as they were dis dicati, days dedicated to the gods.[5] The only labour which the state permitted was that which would cause harm if ignored (quod praetermissum noceret), such as urgent house repairs or rescuing a beloved family ox from a ditch.[6] Such was the solemnity with which the Romans held these occasions.

Their religious nature is important. The festivals did not exist merely to keep the Roman people occupied and away from unrest. The Roman satirist coined the famous phrase panem et circenses, bread and circuses, to refer to a population who only cared about food and entertainment. Today this phrase is used as shorthand for keeping the public engaged with superficial distractions. Roman festivals were not that. The religious aspect of the festivals was taken seriously and significant rituals took place during them. Some of these festivals originated in times of great distress for the Roman state when the public officials felt they had to appease the gods. The Republic began the Ludi Apollinares during the Second Punic War after a plague had ravaged the city. It was only appropriate at that time to dedicate several days to the worship of the god of healing and diseases.

Cicero referred to the ludi Megalenses as illis ludis… quos in Palatio nostri maiores ante templum in ipso Matris magnae conspectu Megalesibus fieri celebrarique voluerunt (“those games which our ancestors wanted to take place and be celebrated on the Palatine Hill in front of the temple and in the sight of the Great Mother herself on the day of the Megalesia”).[7] The presence of plays and chariot races during this festival did not diminish its religious solemnity. It was important to celebrate them properly. It the celebrant did not perform every aspect of the religious ritual properly, the entire festival day had to be repeated in a process called instauratio, repetition. The scholar Lily Ross Taylor estimated that in each year between 207 and 189 BC there were on average an additional five days of ludi scaenici due to instauratio![8] The gods mandated that the Romans take some days off to celebrate these topsy-turvy festivals. In return they would win the favour of the gods. A win-win scenario!

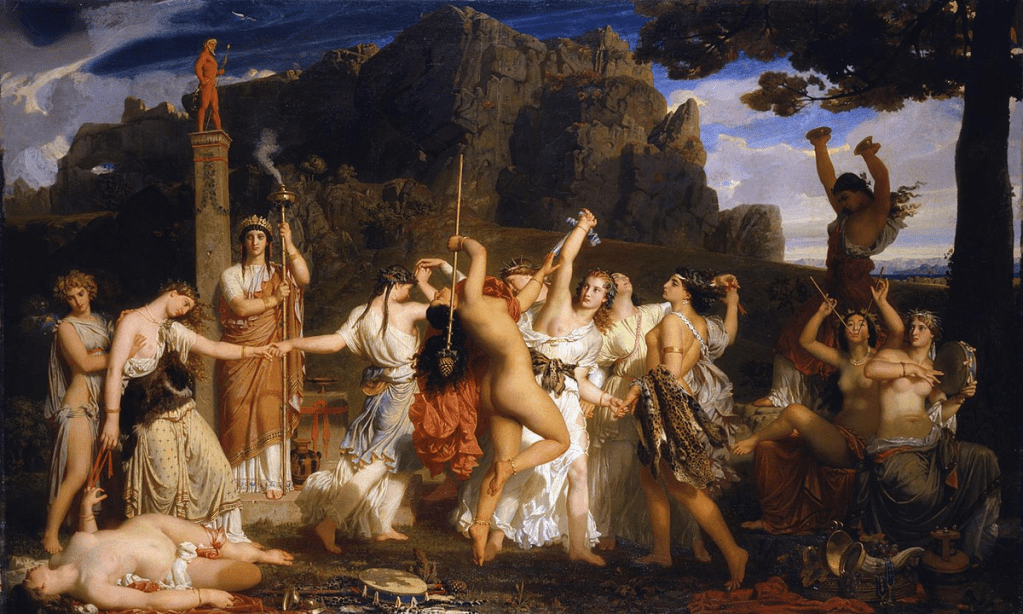

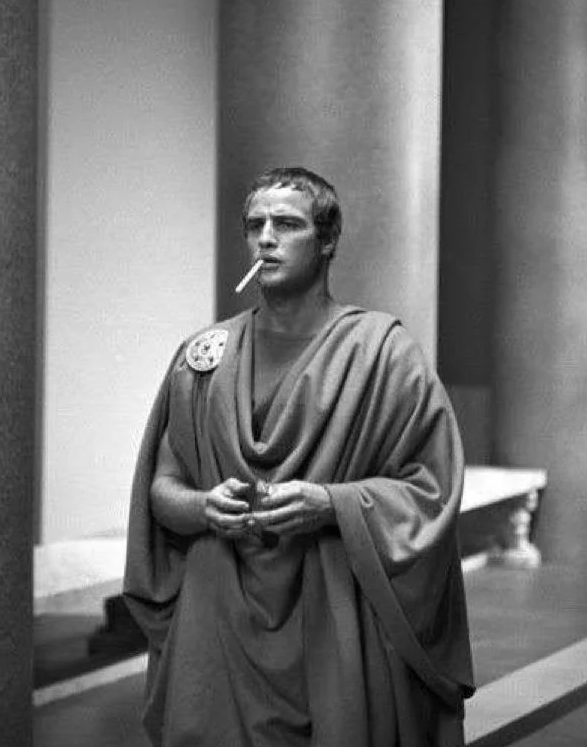

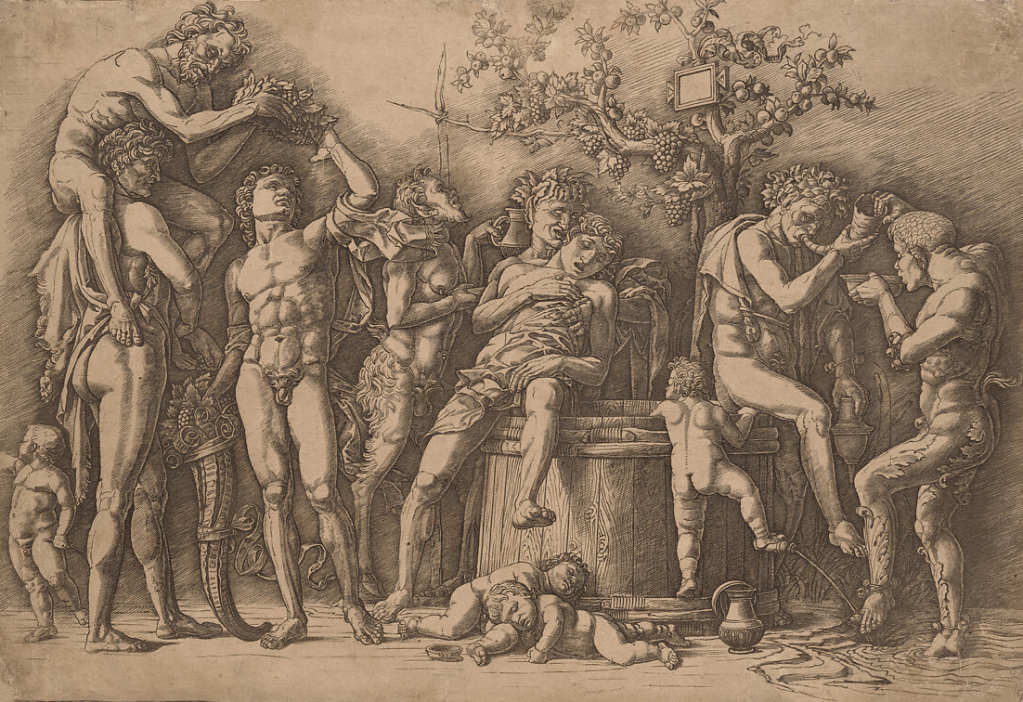

Perhaps the best individual example of the opposite day spirit at play is the Saturnalia. This took place over several days in December, around the winter solstice. It started with a great sacrifice followed by a feast which, it seems, anyone could attend. Senators and knights wore togas for the sacrifice but swiftly donned more informal attire for the banquet, such as a conical felt cap called a pileus – something tantalisingly similar to our modern party hats. Gambling in public was permitted and the festive chant of io Saturnalia! rang throughout the city.

These celebrations were not uniquely Roman. During a discussion on the origin of the Saturnalia, Macrobius’ Praetextus quotes the playwright and poet Accius, who suggested that celebrations in honour of Saturn started in Greece, where it was called the Cronia. Accius suggests that the Romans received one of their most peculiar Saturnalia traditions from this festival: famulosque procurant / quisque suos. nostrisque itidem est mos traditus illinc / iste, ut cum dominis famuli epulentur ibidem (“[during the Cronia] each man takes care of his own slaves. Similarly, the same custom was handed over to our people from there, that slaves dine with their masters in the same place”).[9] This shows just how far the topsy-turvy spirit went: it appears that masters celebrated with slaves. In a society where masters habitually abused slaves and thought them to be less human than their masters, this was world changing.

The poet Horace used the Saturnalia as a setting for one of his Satires, in which his slave utilises his libertas Decembri, December freedom, to criticise his master.[10] On any other day this would be intolerable to a Roman citizen, but the Saturnalia made it possible. The world turned upside down for a few days, and the people expected and celebrated the consequences. A generation earlier, the poet Catullus called this festival optima dierum, the best of days.[11]

Considering how dramatic a shift this change in the master and slave dynamic was, the fact that this festival was so popular is testament to how much the Romans enjoyed opposite day. They loved to flip the natural order of things, if only for a few days at a time. And that limitation was important: the safety of knowing that it will end, that the natural order will return – this being opposite day not opposite life – allowed them to enjoy the events with a sense of security. Horace would only allow his slave to speak his mind with December freedom, not at any other time of the year. If these events took place every day, they would not have had quite the same appeal.[12]

Despite their widespread popularity, some Romans were not so fond of these occasions. The philosopher Seneca noted that although “the city sweats a lot” (maxime civitas sudat) – a rather disgusting image of Rome during the Saturnalia – one should exercise characteristic Stoic moderation: licet enim sine luxuria agere festum diem (“for one may enjoy a festival without luxury”).[13]

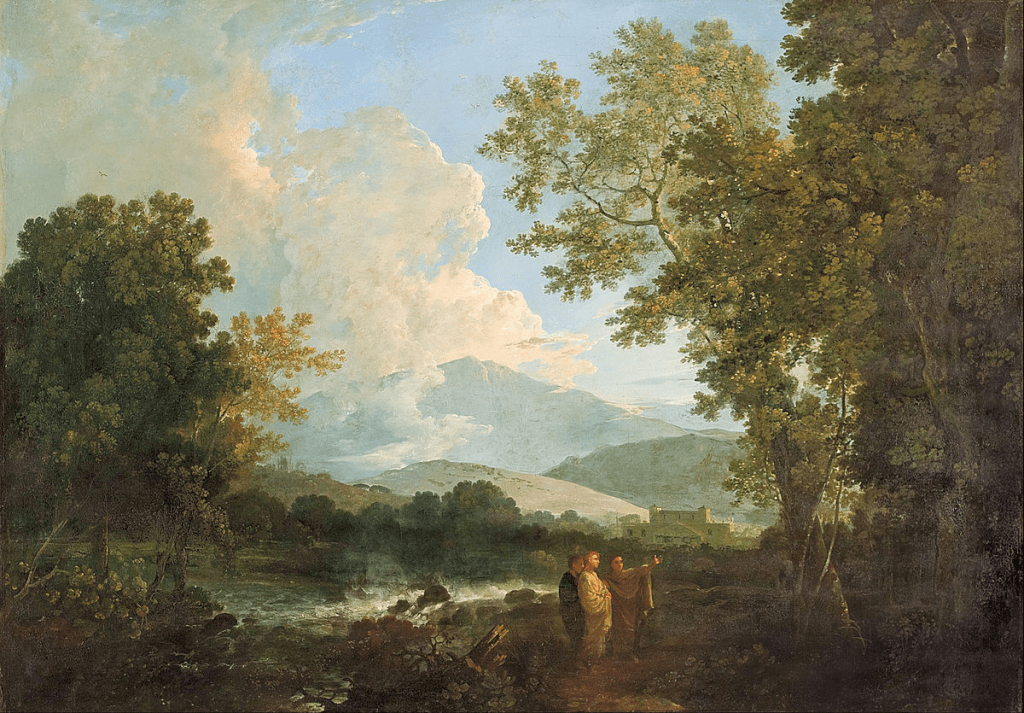

Some authors went further, and there are numerous instances of Classical curmudgeons who saw themselves as above it all. The famed letter-writer and politician, Pliny the Younger,[14] described the chariot races as res inanis frigida assidua: a worthless, dull, common matter. He even congratulated himself for not taking part: capio aliquam voluptatem, quod hac voluptate non capior (“I take some pleasure that I am not taken by this pleasure”).[15] Pliny took measures to avoid his family’s Saturnalia celebrations, retreating to a study far removed from the rest of his villa in order to spend more time with his books. In a pleasing compromise, he reported nec ipse meorum lusibus nec illi studiis meis obstrepunt (“I do not disturb their celebrations and they do not disturb my studies”).[16] The spirit of Scrooge was alive and well in Ancient Rome! Pliny detested the festival precisely because it was an inversion of the usual, and he was so captivated by his habitual reading that he deplored the distraction.

Similarly, Cicero was known to flee Rome during the festive season (in Arpinati… me refeci ludorum diebus (I have refreshed myself in Arpinum… during the days of the games)).[17] Cicero also tells us how the fireman-fat-cat Crassus would likewise retreat to the countryside while the city celebrated: ludorum Romanorum diebus L. Crassum quasi conligendi sui causa se in Tusculanum contulisse (“during the Ludi Romani Lucius Crassus, as if to collect his thoughts, carried himself off to his Tusculan villa”).[18] He would take several companions with him, including one Mark Antony, to conspire. By leaving Rome, these figures were able to enjoy a break from the usual, but in a different way from those celebrating the festival and, importantly, to do so while hidden from the public eye.

However, for populists, it was an equally good time to be seen by the people. Attending the games could show the crowd how in touch a politician was; in fact, the public officials in charge often stumped up a large part of the cost themself. Unfortunately, it didn’t always work. Suetonius notes that Julius Caesar, exercising patrician disregard for public entertainment, caused scandal by his lack of enthusiasm for the Ludi Romani: inter spectandum epistulis libellisque legendis aut rescribendis vacaret (“he spent his free time during the spectacles organising his letters and books or responding to correspondence”).[19] Although this appears to be the ancient equivalent of a political leader scrolling on their phone while attending the FA Cup Final, this is perhaps understandable in such a scenario as the cost of funding games had forced Caesar into debt earlier in his career.

While there are a few exceptions, they only serve to prove the rule. In almost every case, opposition springs from the fact that the festivals were immensely popular and involved a natural element of human chaos. The crowds took to the streets and dominated the public spaces, enjoying spectacles and living a life out of the ordinary for just a few days. The Roman public could freely express their opinions at these festivals and even question the political hierarchy. Cicero cited the great applause heard at the Ludi Apollinares as a public judgment against Mark Antony: Apollinarium ludorum plausus vel testimonia potius et iudicia populi Romani (“the applause at the Ludi Apollinares, or rather, the witness and judgment of the people of Rome”).[20] If there was too much of this kind of public power over politicians, there would be civil strife. However, this inversion was securely contained in a limited form on these festival days.

The entertainments themselves reflect their setting, where the marginalised could briefly have their say. The comedic plays of the festivals are set in normal towns and cities, but often hinge on events out of the ordinary. For example, we find long-estranged twins meeting by chance (Plautus’ Menaechmi) and a distant lover returning to save his sweetheart (Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus). These citizen protagonists are often aided by ‘cunning slaves’ who trick and overcome their masters, such as Syrus in Terence’s Heauton Timorumenos. It is tempting to say that this is explicitly Saturnalian, as this was the festival where slaves were treated as equals to their masters, but unfortunately there is no evidence of its performance having occurred during the Saturnalia. However, in a society which desperately feared slaves revolting, and deliberately demoted them in many aspects of life, and avoided demarking them in a form of shared clothing, these narratives still depict a clear reflection of the extraordinary festival world in which they were performed.

To a Roman mind, humour was not just a trivial matter. Cicero discussed its potential gravitas: quoscumque locos attingam unde ridicula ducantur, ex eisdem locis fere etiam gravis sententias posse duci (“whatever subjects I touch on from which ridiculousness can be extracted, from almost the same subjects serious thoughts may be extracted”).[21]

In normal Roman life a rebellious slave was a serious matter; however, in the strange festival context echoed in comedy, it is laughable – just like the Greek context that spawned these comedies. The effect is reminiscent of the ‘incongruity theory’, whereby laughter emerges from the contrast between a situation and one’s expectations. Equally, the relief theory, which supposes that laughter comes as a relief from pent-up emotion, can go some way to explain why comedies were so appropriate at festivals where the suspension of work was mandated. A discussion of why these plays evoke laughter, and whether that can be theorised at all, is a rabbit hole too deep for this article.[22] However, it is clear that the theatrical entertainments, much like their setting, in some way evoke the spirit of opposite day to comic effect.

In any event, Roman festivals were wide-ranging, highly varied affairs. And, for all that is known about the ancient world, there is so much that remains tantalisingly unknowable. I admit that framing these festivals as opposite days is intentionally provocative. The idea that they were wholesale inversions of normality is far from uncontroversial; they are, perhaps, better understood as a suspension. Nevertheless, there is a clear theme of the extraordinary being at play – the spirit of opposite day in some sense.

It is, for me, a great personal tragedy that I can never attend the Ludi Apollinares or celebrate the Saturnalia nowadays, but some relief can be found in those times when modern cultures similarly suspend normality for just a few days. So next time you find yourself surrounded by carnival rides or theatre festival fliers, consider yourself in the long line of a fine tradition that stretches back thousands of years and has been enjoyed, in between, by countless millions. Or don’t, and join an even finer tradition of curmudgeonry, the likes of which would make Caesar and Pliny puff with pride.

Joel Moore teaches Classics at Charterhouse. He is especially interested in Late Antique Latin education and literature, Roman comedy and early Christianity.

Further Reading

H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell UP, Ithaca, NY, 1981): while this book passed its fortieth year recently, there is not another like it. It is a very accessible index of the manifold celebrations which dominated the Roman calendar with literary references where possible.

W.M. Beard, Laughter in Ancient Rome: On Joking, Tickling, and Cracking Up (Sather Classical Lectures, Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 2014): a very detailed but eminently readable study of Roman humour. Beard’s nuanced study aptly captures the strangeness of Roman sensibilities, without escaping into abstract philosophising. A good primer for understanding what the Romans found funny and why.

Macrobius’ Saturnalia: most of this text concerns itself with Late Antique Roman philosophy. However, the history of the festivals discussed in the first book is worth studying by anyone interested in this topic. It is a good ancient source, although one should approach it with caution if they wish to understand the Roman festivals in the late Republic or early Principate; it comes from the 5th century AD.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Macrobius Sat. 1.1.4. This quotation is taken from a text which is set during a series of dinner parties during a festival season. The speaker, Praetextus, seeks to explain the history of Roman festivals to his curious Egyptian guest. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | H.H. Scullard (1981) 16–18. |

| ⇧3 | Perhaps this is a poor example: for some students, their entire university career is traditionalised revelry. |

| ⇧4 | Scullard (as n.2) 39–40. |

| ⇧5 | Macrobius Sat. 1.16.2. |

| ⇧6 | Macrobius Sat. 1.16.10. |

| ⇧7 | Cicero De haruspicum responsis (On the Answers of the Haruspices) 24. |

| ⇧8 | L. Ross Taylor, “The opportunities for dramatic performances in the time of Plautus and Terence, Proceedings of the American Philological Association 68 (1937) 284-304, at 294. |

| ⇧9 | Accius via Macrobius Sat. 1.7.37.1. |

| ⇧10 | Horace Sat. 2.7. |

| ⇧11 | Catullus 14.15. |

| ⇧12 | We must be careful here: Mary Beard rightly pours cold water on the notion of the Saturnalia as being a full inversion Beard (2014, 63–5); the slaves were still slaves and there is no evidence of their perspective on proceedings. The Saturnalia is best understood as an equalisation, not a role reversal. However, this does not diminish the peculiar, world-changing quality of the day. |

| ⇧13 | Seneca Epp. 18.1-4. |

| ⇧14 | Pliny Epp.9.6.3. |

| ⇧15 | Pliny Epp. 9.6.3. |

| ⇧16 | Pliny Epp. 2.17.24. |

| ⇧17 | Cicero Ad Quintum fratrem, 3.1.1. |

| ⇧18 | Cicero De Orat.1.24. |

| ⇧19 | Suetonius Aug. 45. |

| ⇧20 | Cicero Phil.1.36. While it is clear that this is an attack on a political rival, that need not invalidate the claim. Seeing as the Ludi Apollinares were so popular, would Cicero have hazarded an accusation which so many citizens could discredit? |

| ⇧21 | Cicero De Orat. 2.248. |

| ⇧22 | That said, Mary Beard’s excellent book Laughter in Ancient Rome is a good place to start, as is this Antigone article. |