Harry Tanner

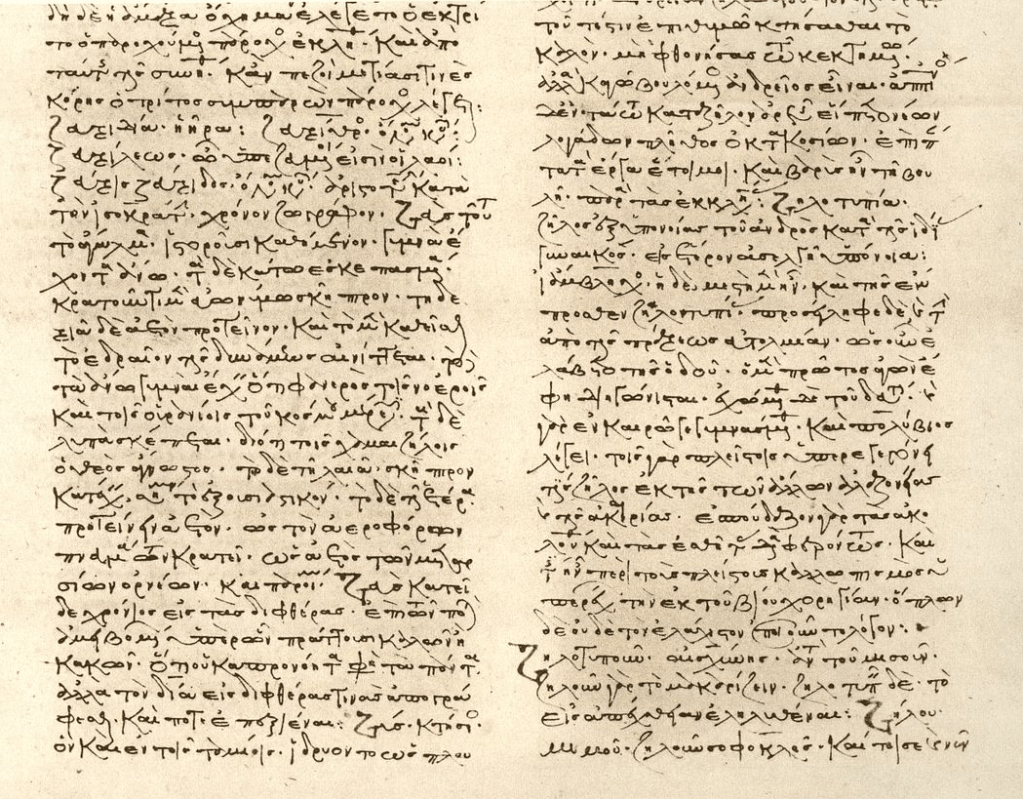

The story of how a team of scholars and students in Oxford compiled one of the world’s most famous ancient Greek dictionaries reveals the remarkable pace of technological change in the study of this language. The ‘LSJ’ (= Liddell, Scott, and Jones — Liddell and Scott being the original authors and Jones a later editor), or ‘The Lexicon’ (as it is affectionately known), was put together by a team of students who painstakingly recorded words encountered, along with their contexts, on index cards for Liddell and Scott to sort and to categorise. Very little is known about the criteria by which Liddell and Scott decided what each word meant; there is no preface, no introduction, no explanation about the methods by which these scholars arrived at their conclusions and – more to the point – their translations. This lack of explanation perhaps reflects a more generalised self-confidence of scholars in the 19th century: as E.H. Carr said of historians of that era, “they believed [history’s] meaning was implicit and self-evident.”

The great scholar of Greek John Chadwick (1920–98) noted that LSJ and its translations are far from perfect: in his Lexicographica Graeca (1996), he exhorted the reader that it was “time to stop worshipping this ancient monument and to replace it with more modern structures”. In the 21st century, we have digital tools which can fetch every single use of a word in every century, ordered chronologically, in a few seconds; this feat of technological progress makes Liddell and Scott’s efforts seem medieval by comparison. The question is — what to do with these new tools? How can individual philologists and students of ancient Greek deepen and enrich their own understanding of the language in a way that furthers the strides made by Liddell and Scott?

The Difficulty with Dictionaries

One of the key problems with dictionaries lies in how we tend to think about words, not least words in ancient Greek. We tend to think of them as existing somewhere in the mind with a definable, clear meaning — as if a word like “beauty”, or “mellifluous”, or “carrot” had a home, a clear piece of real estate in the mind, a mental dictionary entry. This limiting idea is far from new. In Plato’s Laches, Socrates asks, πειρῶ εἰπεῖν ὃ λέγω, τί ἐστιν ἀνδρεία (try to articulate what I am saying, what is andreía?) (Laches 180e). What ensues is an attempt to define the word — to say what it properly means. The assumption at the heart of this dialogue, as well as at the heart of LSJ, is that words have true meanings which exist independently of the contexts in which they are found. It’s as if there is some mental catalogue in which we might look up a word and learn all there is to know about its meaning. But, of course, words are never that simple, and to pretend that they are risks missing out on all the polysemy and multivalence inherent in poetic and creative language.

The word andreia, Plato assumes, has a pure, unadulterated meaning outside of context, and it is our job to find it. Similar attempts are made in the Charmides on the word sōphrosunē (σωφροσύνη). Dictionaries seek to capture that idée mère — to describe in sundry words what it means. Following suit, LSJ glosses σωφροσύνη as “soundness of mind” — another attempt to provide a glancing, unified definition which neatly captures all there is to know about the word. Unfortunately, such assumptions tend to deprive us of the chance to appreciate the beauty and poetry of words.

One quick glance at Adriaan Rademaker’s elegant study of σωφροσύνη (2004) is quite enough to disabuse the reader of any notion that this varied and diverse ecosystem of contexts, ideas, and meanings could ever be usefully summed up by a phrase like “soundness of mind”. As Rademaker shows, σωφροσύνη can be used to describe the mental will to avoid desire, exemplified in the chaste behaviour of Electra’s husband — a simple farmer — who refuses to lay a finger upon her (Electra 261). In Aeschylus, σωφροσύνη describes Amphiaraus’ peaceable, non-violent nature (Seven Against Thebes 568).

The complex network of thoughts and ancient ideas which weave between these two uses reveals a web of notions about the world which can hardly be summed up by the simple phrase “soundness of mind”. It is usually possible to perform the intellectual gymnastics necessary to validate most definitions; so, to be clear, I am not disputing that they can be summed up by LSJ’s definition. Instead, I am disputing that they should. To rely on short definitions, at the expense of deep exploration of a word’s meaning, can be disappointingly reductive.

The tendency to assume words have unifying, homogenous definitions is as intrinsic to Western thought as the mind-body divide. The cover of the much-hailed Cambridge Greek Lexicon promises to show students the “relationships between… senses”. As we have seen, such relationships between senses are enormously helpful in organising complex dictionary entries for students, but they don’t reflect the reality of how the mind processes word meaning. The Cambridge Greek Lexicon is an exciting and welcome contribution to ancient Greek pedagogy. But these unifying definitions come with a very real cost: in excising a word from its context, you remove the complex web of ideas and concepts to which it is attached, and in doing so, you risk losing nuances, subtleties, connotations — in short, the poetry and the richness of the ancient Greek language.

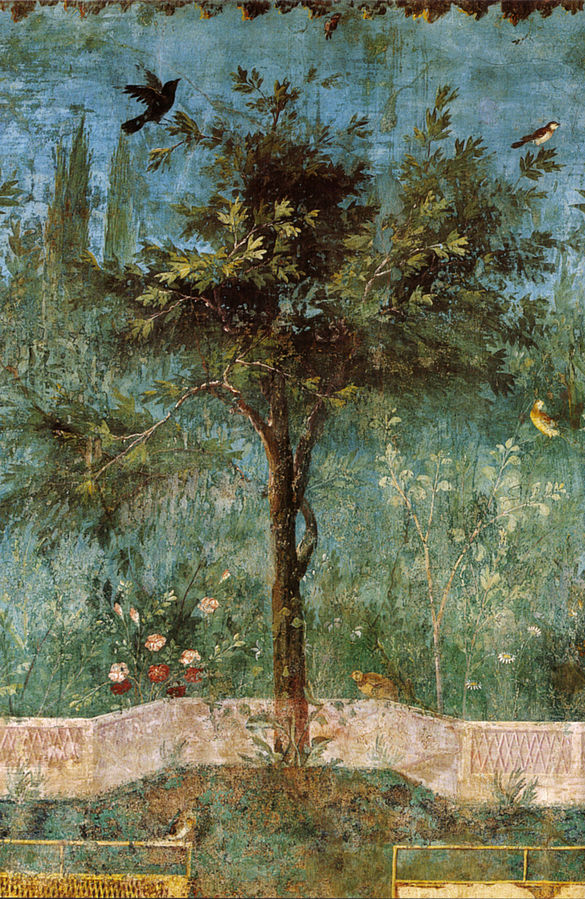

Anthony Burgess compared a word in a dictionary to a car in a showroom: “full of potential, but temporarily inactive.” I am more moved to think of it like a dead, stuffed canary, pinned mercilessly to a display cabinet in the Natural History Museum for the general amusement of sulky schoolchildren. In reality, a word belongs to an ecosystem of other words, ideas, concepts, and it can only be fully appreciated in the wild. But the question is: how can a student of Ancient Greek see a word — so to speak — in the wild? How can they free themselves from the confines of a narrowly-defined dictionary entry?

How to Build a More Sophisticated Model

The approach Rademaker takes in his 2004 study of σωφροσύνη is to group each use of a word into ‘clusters’ in an arbitrarily defined group of texts. For instance, there is a cluster of uses for self-restraint in the historical corpus of the 5th century BC, primarily the works of Thucydides and Herodotus. This echoes the approach taken by cognitive neuroscientists working on language comprehension, who have found that there is no centrally located storage point for a single word’s meaning anywhere in the brain; rather, it is scattered messily across a variety of domains and contexts.

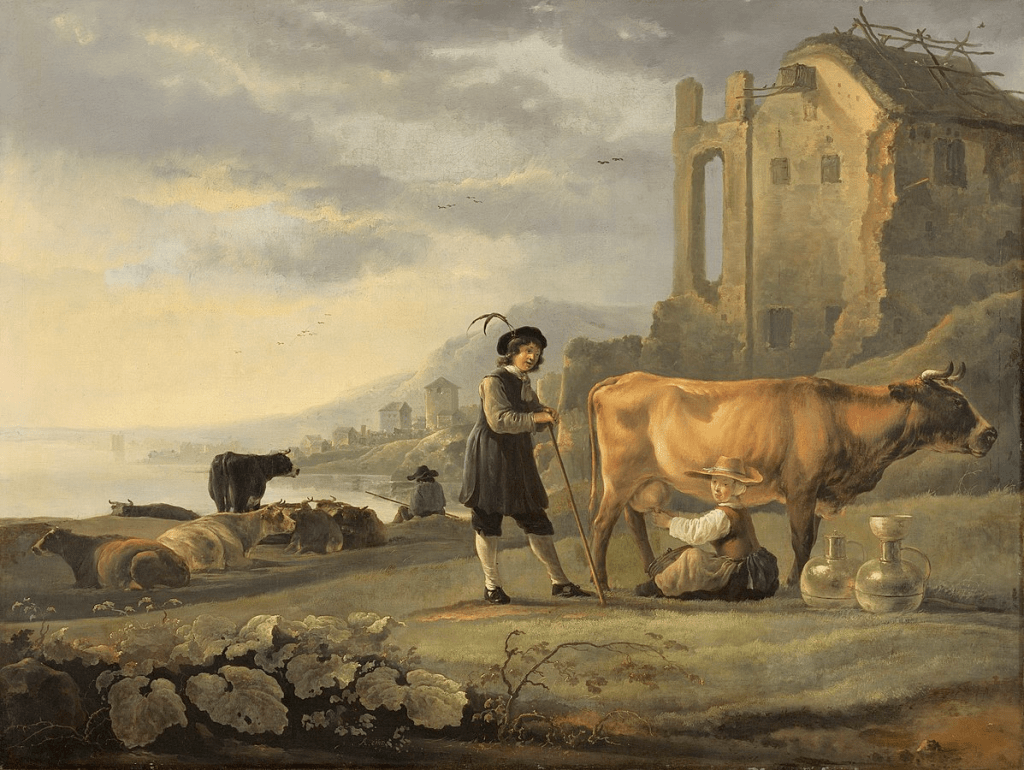

For example, there is no place in the brain where the word “udder” is stored. Rather, ideas about udders are scattered willy-nilly across a variety of different messy contexts and situations — from farms to milking to dairy to ice-cream manufacturers. In each use, it is the context which draws us to its appropriate meaning; the brain — apparently — does not look up the word “udder” in some invisible, mental dictionary. I don’t think this finding should surprise us, but it is useful to have this flexible account of word meaning confirmed empirically. When we comprehend sentences, we tend to use all available information in the context to access meaning, and we fill in the gaps when we don’t fully understand what’s been said. This is another of those sensible things Wittgenstein said, and yet it clashes quite definitely with the way we have been taught to comprehend word meanings in an ancient language.

I would imagine that most people’s instruction on how to use LSJ follows a similar pattern to my own: encountering a word you do not know, you thumb LSJ — or with a few, satisfying mouse-clicks and keyboard-taps acquire its corresponding digital entry — and find its definition. I’d imagine too that I am not alone in finding most of these definitions unsatisfying. The sinking feeling one gets when reading a phrase like “representation by means of lines” (the entry for γραφή) is remedied only by the curiosity this ignites — the urge to understand better what this word truly meant for men and women thousands of years before us. When I read works in a modern language, I feel I have a much stronger grasp over meanings, nuances, and connotations. How do we get there for Ancient Greek too?

A Simple Example: Going Further than LSJ with Sappho

In the 31st fragment of Sappho’s works, we are bequeathed a mawkishly vivid image of her physical experience of desire. Most curious is her description of herself as χλωροτέρα… ποίας, which has been variously translated “greener” or “paler” than grass. Is this a simple reference to the pallor of her skin? If so, why compare it to grass? Is she green with envy? A disappointing thumb through LSJ would tell you that it means “pale”. As Burgess said — a word in a dictionary is like a car in a showroom. What if we seek to understand this word in its usual context? What if we take the car for a spin?

In our earliest works, χλωρός captures the emotion of soldiers shaking in terror before the walls of Troy, or the suitors in the presence of Odysseus, or the sailors staring into the mouths of Charybdis and Scylla. It also describes the soft and moist pliability of freshly cut wood, and the fearful, trancelike state induced in unwary drinkers of drugged wine. In light of these clusters of different contexts, Sappho’s phrase seems more nuanced. She’s capturing her fear, as well as the drug-like state that desire imposes upon her, while simultaneously characterising herself as pliable, moist, supple, and delicate — χλωροτέρα ποίας, “more khlōros than grass”. She is at once afraid, and left weak at the knees, soft and pliable like grass. To return to the car showroom, LSJ’s “pale” seems a little paltry by comparison.

How to Explore by Yourself

Sappho’s poetry offers one small example of the richness available to those who will go further than LSJ’s pages. We should forgive the editors of LSJ: the fruit of that extraordinary labour of noting down all uses of interest on index cards and then going through them painstakingly is still a marvel to behold. But we have more powerful tools at our disposal now: the Perseus Digital Word Study Tool, and the digital Thesaurus Linguae Graecae. The time it takes for the latter website to compile a near-complete list of all uses of a word in chronological order is barely sufficient to plunge the lever on my cafetiere. What once took months of painstaking labour takes seconds now. So, how best to make use of these marvellous tools?

It depends on how seriously you want to take a word. Some words can be very serious undertakings, with many thousands of uses. Others can comprise just 30 uses between Homer and the 3rd century BC. If you encounter a fiendishly common word, you might select a corpus in which you are interested. You might just look at the word’s use in tragedy, or in history, or in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. That said, the process of a thorough study of a word and all its whole ecosystem is an enormously satisfying undertaking. The study of an ancient language never was a hasty exercise. Ancient Greek, which has been around for some three thousand years, has become accustomed to waiting.

My recommendation would be to use the digital tools to create a small pool of word uses in the period and genre of texts in which you are interested. Then proceed to annotate each of them, loosely describing its meaning and context, without providing a translation or a definition. I recommend either printing out the uses, or exporting them to a PDF and annotating them on an iPad. It’s very important — to my mind — to describe the whole meaning of the sentence and the word’s role in it; don’t try to translate it. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, at line 190, khlōros captures some quality of the fear which took hold of the queen as she looked upon the goddess. This is in many ways more accurate than simply translating it as “pale” or “fresh”: it captures the word in its ecosystem. There is no risk here of foisting meaning onto a context where it does not belong.

In this way, you can imitate the process undertaken by the students and editors of LSJ in previous centuries. Crucially, the difference is that you are not seeking certainty in a clear translation: you are seeking to understand the context, or ecosystem, the word inhabits each time. In short, you are seeking to replicate roughly and imprecisely the process by which modern languages are acquired: a gradual exploration of all the nooks and crannies in which a word can be found.

Next, group the word uses together into loosely fitting clusters — where each use overlaps in meaning or in context. You might, as I did with khlōros, group together the fear of the sailors staring down Scylla and Charybdis with the fear of the suitors into a single cluster, but you will probably find subtler delineations. Some of these clusters are very tight-fitting and neat, others are much sparser. Once you have done so, return to the word in which you were interested — you may find nuances and connotations that you had previously missed. Above all else, this is about discovery — finding new insights into old texts.

Key to this process is the understanding with which we began: word definitions are a poor substitute for the rich diversity of meaning which can be found in context. But another key is a constant awareness that our understanding of the meaning of Greek words is filtered through the languages of our dictionaries. By relying wholly on English as the proxy for the meaning of words in ancient Greek, we miss the rich diversity of the contexts to which the Ancient Greek word originally belonged. Thinking of khlōros not as “green” or “yellow” or “pale”, but as belonging to the context of war or the terrors of the sea, or the soft, wet quality of freshly cut wood is a far more vivid image; it brings the text, and its words, alive. Context — not definition — is the key to accessing more of the poetry. It is also key to grasping this slippery and challenging language meaningfully.

A further treasure awaits the patient student of Greek lexicology. As you annotate and catalogue a word’s many contexts, their clusters, a picture will begin to emerge of what happens to words as time proceeds. As if pulled by some indiscernible gravity, the contexts in which words sit are gradually and imperceptibly drawn into new, neighbouring contexts. The word κίων (kiōn), originally a wooden pillar which holds up the Homeric feasting hall, and the post which Odysseus used to torture the suitors, is picked up for the torture of the Titans. Strapped to these posts, they endured the wrath of the immortal Olympians. Over time, as the Greeks began to associate these loci of torture with mountains, κίων is drawn into use for mountains, and then hills, and — by the time of Xenophon — κίων is used for small mounds of earth. Like a biologist surveying the minute shifts in the fossil record, a philologist observing subtle shifts in context can see this semantic drift at work.

From spotting new patterns in poetry, new links in old works, to observing the gradual drifts in lexical use over many centuries, the new world opened up by these digital tools promises an astonishing vista. The compilers of LSJ would grind their teeth in envy if only they knew the muscularity of the digital tools at our disposal. But what to do with your new discoveries?

How to Share your Findings

A venue already exists, which I think should be more widely used than it presently is. Wiktionary is an online and freely accessible dictionary. There is already a thriving community who adds and updates Ancient Greek and Latin words, as well as their etymologies. Importantly, Wiktionary is also free for anyone to edit. I think it would be wonderful if students of lexicology and philology who believe they have found an interesting use added it to Wiktionary where it can be reviewed and checked by other members of the community. Nobody takes Wiktionary to be a gospel source such as LSJ or any other dictionary, but it could be a fascinating source of inspiration and supplementation to those reading texts at speed. We could — as a community — build a hive-mind of all the many clusters and contexts observed by thousands of different philologists. The internet not only enables us to index words faster, it enables us to collaborate with exponentially larger numbers of people.

We live in an age when anyone can contribute to the deepening of our collective understanding of ancient texts. It is an age of digital tools to search, catalogue, and then to share findings. The student of this process can enjoy the private delight of engaging more deeply and more vividly with the words of the past, and can share those findings with a broader community. This is the age into which Ancient Greek lexicology is advancing. That is certainly not to say that LSJ does not have its place. It remains a monumental effort of will and an extraordinary example of scholarly endeavour. But the new field of Ancient Greek lexical semantics — of clustering lexical uses by context, and watching delightedly as they drift into new areas of meaning — is much more democratic and capable of being far more compendious than LSJ ever was. I’ll always regard ‘the Lexicon’ with deep affection and cherish my copy, but I’m very excited by how these new, more flexible ideas about word meaning, combined with the tools to investigate ancient uses, will propel us into a new age of Ancient Greek and Latin philology.

Harry Tanner completed his PhD at University of Galway entitled “Ancient Greek Lexical Semantics: Word Meanings as a Function of Context”, under the supervision of Prof. Michael Clarke and examined by Prof. James Clackson. He researches at the intersection of historical linguistics and cognitive neuroscience, with a particular focus on Ancient Greek lexical semantics. He is currently working on his book The Queer Thing about Sin (Bloomsbury, 2025), which traces the link between wealth inequality, self-control, and homophobia from 7th-century Greece to the time of the Early Christians.

Further Reading

To begin with, an excellent introduction to the problems with current approaches to Ancient Greek lexicography is Louw (1989). Another excellent overview article on Ancient Greek lexical semantics, which focusses particularly on the use of prototype theory, is Clarke (2010). For a history of LSJ, see Stray et al. (2019). For an excellent, nuanced study into Ancient Greek lexical semantics of self-restraint, see Rademaker (2004).

For a wider history of dictionaries and an overview of how definitions are written, see Hanks (2015). For an overview of theoretical approaches in linguistics to semantics, see Geeraerts and Geeraerts (2009), though this account crucially misses developments in the cognitive neuroscience of language. This more modern approach now supersedes previous attempts to understanding meaning in terms of prototype theory. For the role of prototypes and salience in comprehension, see Giora and Giora (2003). Prototype theory explains how the brain selects meaning in a context-poor situation, for how the brain constructs these context-poor representations of meaning, see Nozari and Thompson-Schill (2016). Most words are encountered in context, for an overview of the more recent field of cognitive neuroscience of language and lexical comprehension, see anything by Kara Federmeier, particularly Federmeier, Kutas, and Dickson (2016). For an overview of this literature, and its integration into historical linguistics, as well as a number of case studies on Ancient Greek, see my PhD thesis held at the University of Galway (submitted 2022).

M. Clarke, “Semantics and vocabulary,”in E.J. Bakker (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language (Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, 2010) 120–33.

K.D. Federmeier, M. Kutas, & D.S. Dickson, “Chapter 45 – A common neural progression to meaning in about a third of a second,” in G. Hickok & S.L. Small (edd.), Neurobiology of Language, (Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2016) 557–67.

D. Geeraerts, Theories of Lexical Semantics (Oxford UP, 2009).

R. Giora, On Our Mind: Salience, Context, and Figurative Language (Oxford UP, 2003).

P. Hanks, “Definition,” in P. Durkin (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Lexicography (Oxford UP, 2015).

J.P. Louw, “Words and meanings – a semantic problem,” Akroterion 34 (1989) 238–43.

N. Nozari & S.L. Thompson-Schill, “Chapter 46 – left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in processing of words and sentences,” in G. Hickok & S.L. Small (edd.), Neurobiology of Language, (Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2016) 557–67.

A. Rademaker, Sophrosyne and the Rhetoric of Self Restraint: Polysemy and Persuasive Use of an Ancient Greek Value Term (Mnemosyne Supplements 259, Brill, Leiden, 2004).

C.A. Stray, Christopher, M. Clarke & J.T. Katz (edd.), Liddell and Scott: The History, Methodology, and Languages of the World’s Leading Lexicon of Ancient Greek (Oxford UP, 2019).