Lola Teale

As an historian as well as a passionate musician, I have been struck by the difference in depictions of Odysseus’ encounter with the Sirens, as seen on Greek vases versus Etruscan funerary urns during the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC). The subject remains the same but it is realised in radically different ways.

Throughout the ancient Mediterranean, there was considerable commerce, not merely in the economic sense of the term, but also with respect to knowledge and art. Artists often travelled from place to place, bringing their ideas, techniques, skills and styles with them, whilst also learning from (and competing with) their peers and rivals. Of course, local and national differences in artistic representation are not always the result of conscious cross-pollination. Sometimes the stories themselves differ. Let us look at how depictions of Odysseus and the Sirens change, depending on location, local tradition, a given society’s fashions, and popular tastes.

In the Beginning There Was a Myth

According to Ovid’s version of the myth (Metamorphoses 5), Persephone was kidnapped whilst playing with friends who could not protect or defend her from Hades, god of the Underworld. Demeter, Persephone’s mother, gave them wings to help search for her daughter; however, in the account of the myth given by the mythographer Hyginus (also written in the Augustan period) Demeter was so angry at her daughters’ friends that she cursed them, turning them into singing half-bird creatures. It was foretold (not just by Hyginus, but also according to his Alexandrian predecessor, the poet Lycophron) that these ‘Sirens’ would die once a man was able to pass by them without being enchanted by the charming voice of their songs.

Lycophron and Pseudo-Apollodorus (author of the mythological handbook the Bibliotheca) say that there were three Sirens: Leucosia, Partenope and Ligea. They are first encountered in Book 12 of Homer’s Odyssey, where it is implied that there were only two, not three. Apollonius of Rhodes, in the fourth and final book of his Argonautica, recounts how Orpheus drowned out their singing with his superior musical talent.

In the Homeric account, Odysseus managed to listen to the Sirens’ irresistible song without suffering any consequences by ordering his men to stop their ears with wax, and then bind him to the mast of the ship. As a consequence they all sailed safely past without being enchanted. Hyginus and Lycophron add the detail that the Sirens reacted to their failure by throwing themselves into the sea. Some post-Classical mythographers assert that their bodies were then transformed into rocks.

Ancient Greek Sirens

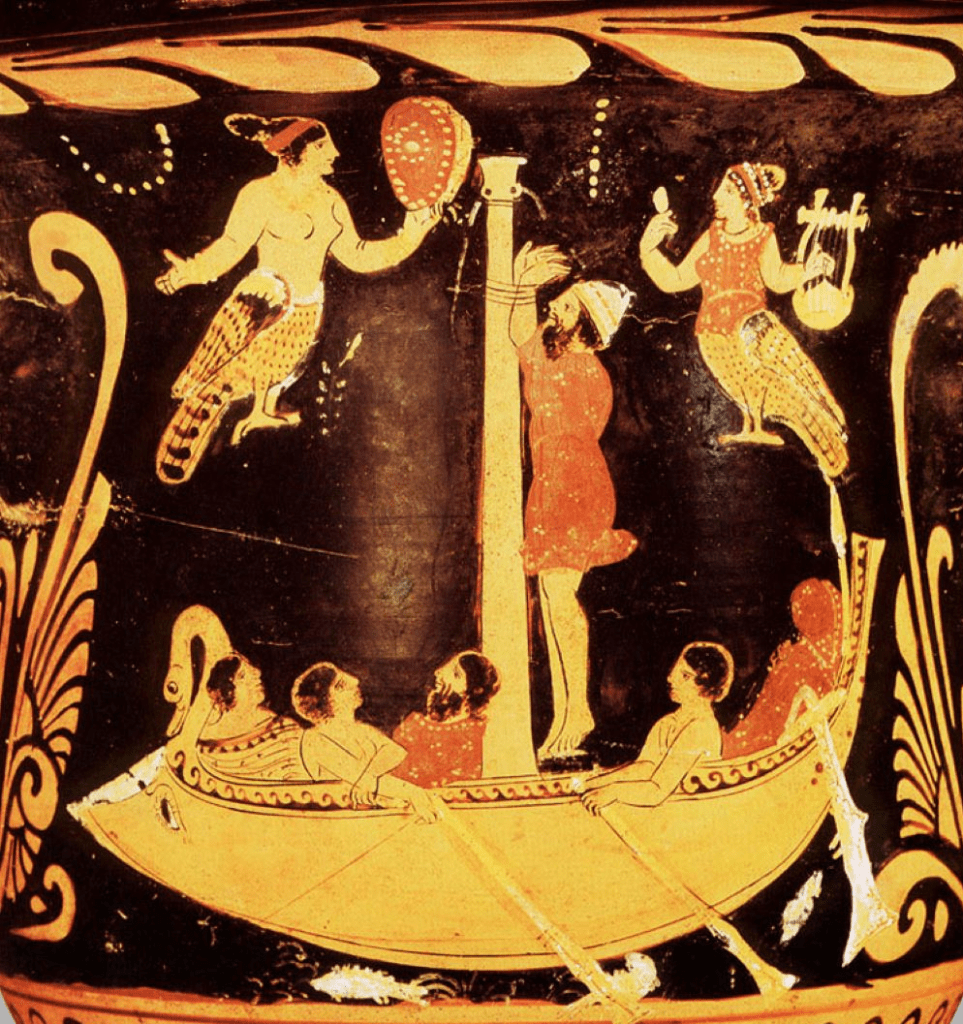

On Greek vases, the Sirens are depicted flying around Odysseus’ boat while playing stringed instruments and (apparently) singing. In the Greek musical tradition, the human voice played a leading role in musical performance: the purpose of musical instruments was mainly to accompany singing. When depicted on vases from this particular culture, the Sirens tend to play a lyre or kithara; the rows of dots in such images appear to be an attempt to represent sung music, as on the krater below.

So far I have found no images of a ‘syrinx’ – the pan-flute or panpipes – being played by Sirens on Greek vases, or otherwise in Greek art. The image below also boasts a rare depiction of a drum (see the Siren on the left):

Sirens in the Greek-speaking Colonies of Italy

Being only half-human at most, the Sirens had the power to go back and forth from the Underworld, as can be seen in a votive jug from Croton (see below), on which a Siren is depicted holding a pomegranate in one hand, and a syrinx in the other. The pomegranate is one of the distinguishing features of Persephone, whilst the syrinx is the instrument that was purportedly used to help conduct the dead to the underworld, whilst also consoling with its music the still-living who were bereaved. The syrinx conventionally boasts seven reeds which, according to Pythagorean theory, symbolised both celestial harmony and the ‘seven planets’.

Pythagoras himself (c.570–495 BC) did not in fact create the Pythagorean astronomical system for understanding the seven ‘planets’, which were loosely defined as heavenly bodies that are visible to the naked eye and can be seen to move through the sky; these we now know as the Moon, the Sun, Venus (Aphrodite), Mercury (Hermes), Mars (Ares), Jupiter (Zeus) and Saturn (Cronus). Not all ancient cosmologists thought of the Earth as a ‘planet’ itself: during the Roman imperial period, the astronomer Ptolemy (AD 100–70) famously perfected his definitive astronomical model in which the Earth was the centre of the universe (a vision which was not superseded until the Renaissance).

Pythagoreans sought to harmonise music with mathematics, the physical sciences, and everything else. In this Pythagorean interpretation of the syrinx, each of the intrument’s seven reeds symbolised one planet: the lowest was Cronus, the sun was at the middle, and the highest-pitched note was the Moon.

Etruscan Sirens

Throughout the Hellenistic period in Etruria, Odysseus and the Sirens were a common subject on men’s funerary urns. The subject is attractive in itself, and perhaps demonstrates more than the deceased’s love for Greek culture. For whatever reason, funerary urns of this sort were mass-produced in bulk, and enjoyed an unusually widespread distribution.

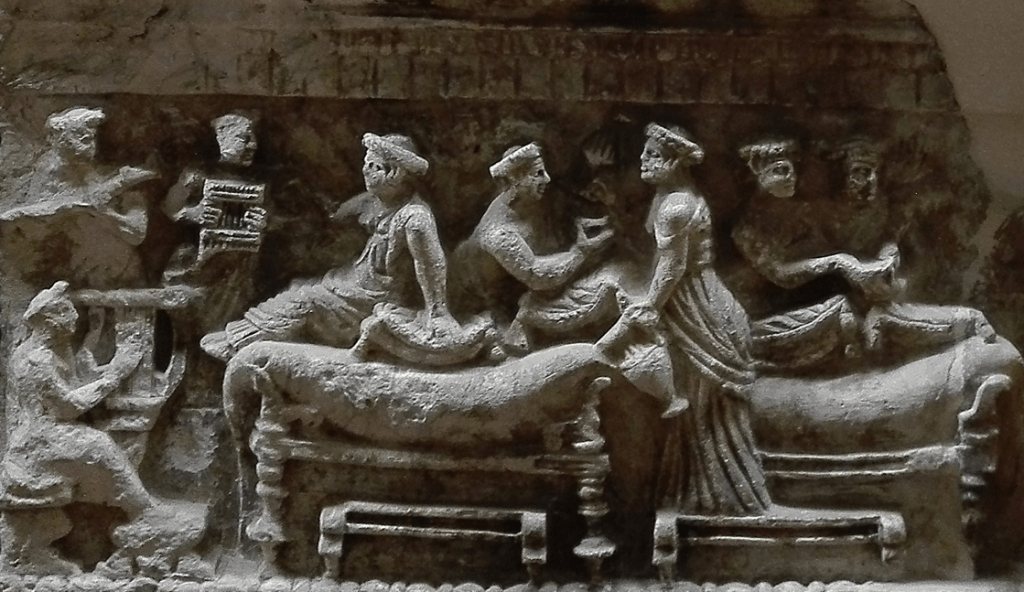

The Guarnacci Etruscan Museum in Volterra, Italy, provides an opportunity to study a number of these urns in varying states of conservation. All share the same general characteristics, and depict this scene using the same composition: on the viewer’s right stands Odysseus’ boat, while the sirens to the viewer’s left seem to elaborate considerably on the scene as described by Homer.

The Sirens are good-looking women; they wear refined chitons, and sport fashionable hairstyles. They sit atop a cliff in a line, each playing their own musical instrument: one plays the kithara, the middle one has a syrinx, and the last plays the auloi. This is one of the first known depictions of a women’s musical ensemble: the syrinx plays the bassline, whilst the kithara accompanies the auloi, which play a charming melody that, unfortunately, we can no longer hear.

The musicians seem so real that they appear to represent something that really existed at the time, as so often seems to be the case with Etruscan art. The Etruscans represented their traditional myth, stories and histories using contemporary life as a model. Thus the clothes in Etruscan art tend to be those that were fashionable at the time the art was created, the instruments are those you could have seen being played in that part of the world, and all the tools, food and so on were similarly real and contemporary. All this gives us important insights into Etruscan daily life and history, which otherwise seems so obscure to us, since the Etruscan language and its literature are essentially lost to us.

Musical Instruments: The Syrinx

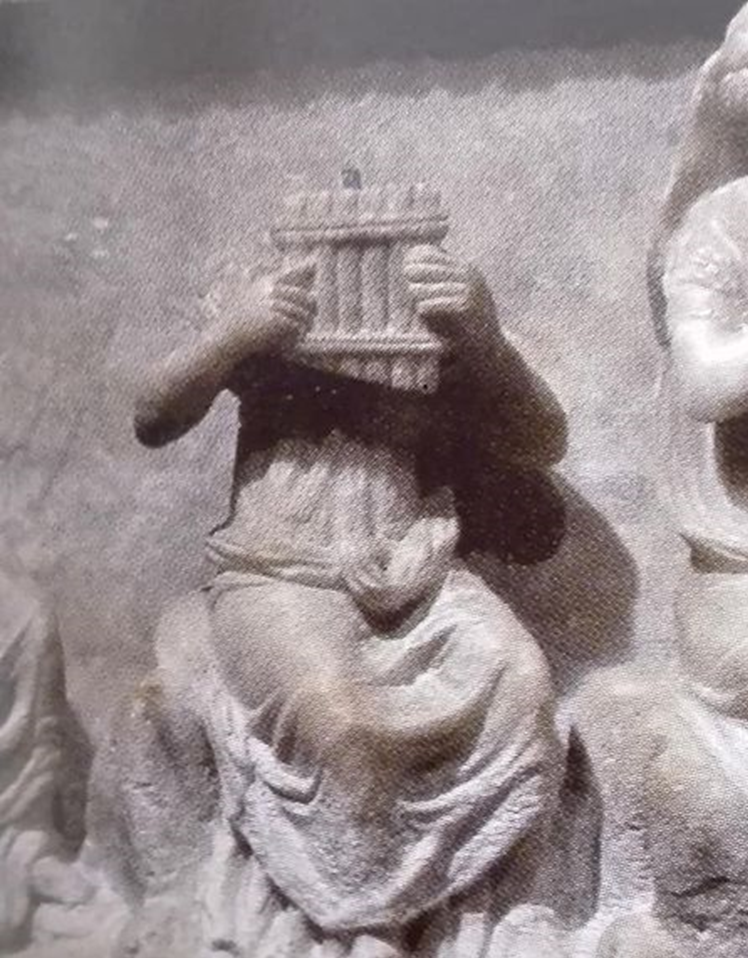

I am particularly struck by the presence of a syrinx in this musical ensemble. In most instances, the syrinx is associated with the god Pan, the nymphs, and the pastoral life of the sort that is depicted in Longus’ Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe (2nd century AD). But here, on this urn, the syrinx has been promoted from the status of a shepherd’s instrument, a mere accompaniment to singing, to a full member of a small concert ensemble. Given the size of the syrinx depicted on these urns, it appears to have been used as a drone.

The use of the syrinx as a drone is also shown in another Etruscan urn of the same period, albeit one which represents a different situation entirely – a symposium:

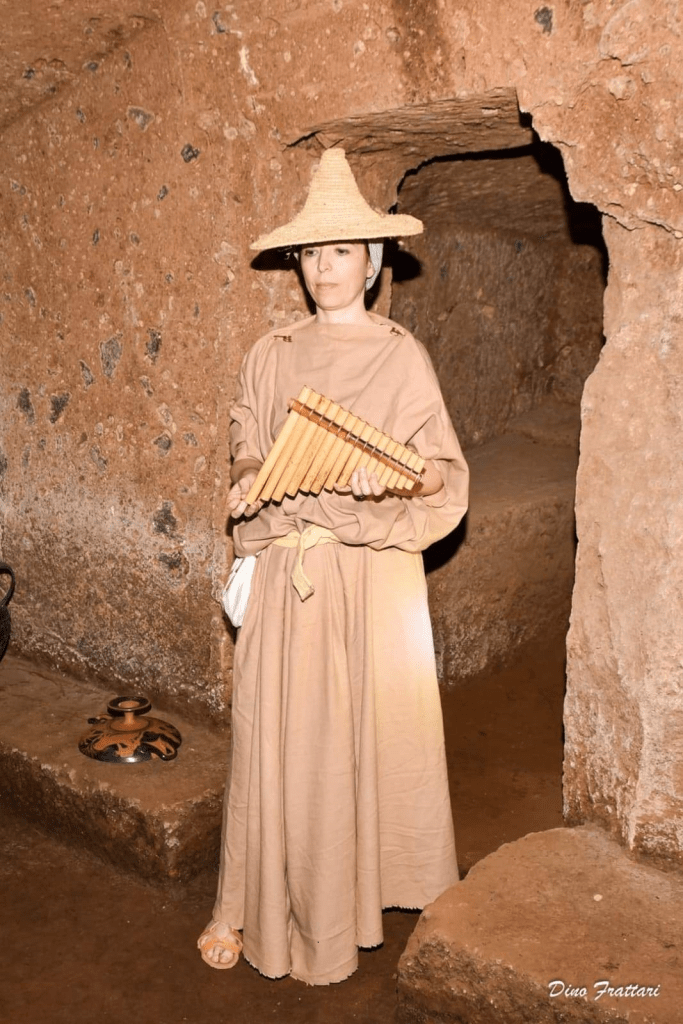

A Living History Experiment

In August 2022, I was invited to take part in an Etruscan ‘living history’ event. Since then I have studied not only Etruscan life and history but also that culture’s music and musical instruments. I fell in love with the syrinx, and have decided as a result to try to recreate one of the Hellenistic reliefs I have described that you can see in Volterra at the Guarnacci Museum, in which the Sirens do not sing, but play music instead – perhaps in keeping with an Etruscan preference for instrumental music.

The Chiton

I paid close attention not only to the music I tried to play, and the instrument on which I played it, but also to my Siren’s outfit. To make my chiton, I first measured the length between my wrists, and then the height from my neck to my ankle. I then obtained two pieces of linen of appropriate size, and sewed them together on three sides, leaving three holes (one for my head and two for my arms). To appear even more like the Sirens on the reliefs, I gathered the billowing fabric along the front of the chiton, and tied it up using a wide woollen belt that I wore around my waist. The result looks like the sort of chiton (not unlike a dress with sleeves) as can be seen in ancient Etruscan reliefs and wall paintings. The colour of the linen I selected is meant to recall the colour of the sea.

The Syrinx

I did not wish to make a mere toy syrinx, so I studied those Etruscan Siren urns on which the syrinx was in a good state of preservation. My syrinx is large, as can be seen above, and is made from pieces of a wide, well-seasoned reed. The notes I can play are: C, B, A, G, F, and E: that is to say, it can play tunes in the Lydian mode.

To tune my instrument, I thoroughly cleaned the inside of each reed, sealed the bottom of each one with beeswax, and poured wax through them, then oiled the entire instrument with linseed oil, both inside and out.

Conclusion

This experiment helps remind us of how the past can still surprise us in countless little details. The scholarly materials that I have consulted tend to dismiss the syrinx as a mere low-status pastoral instrument – an ancient equivalent of the modern ‘harmonica’, or mouth-organ. But clearly it might have played larger, more wide-ranging roles in ancient musical culture. My next task will be to test my intuition that the syrinx might have been used not only as a drone but also as a leading instrument on certain religious occasions, or in situations where the auloi might have been considered too loud, or shrill.

Lola Teale lives in Tuscany, Italy, the cradle of the Etruscan civilization. She has always had a passion for history and took a university degree in that subject. Reenactment has allowed her to spread her historical knowledge. Her main sectors of interest are music, calligraphy, and the history of the pan-flute, which she constructs according to ancient descriptions and regularly plays.