Isabella Redmayne

“The classics can console. But not enough.”

Derek Walcott, Sea Grapes (1992)

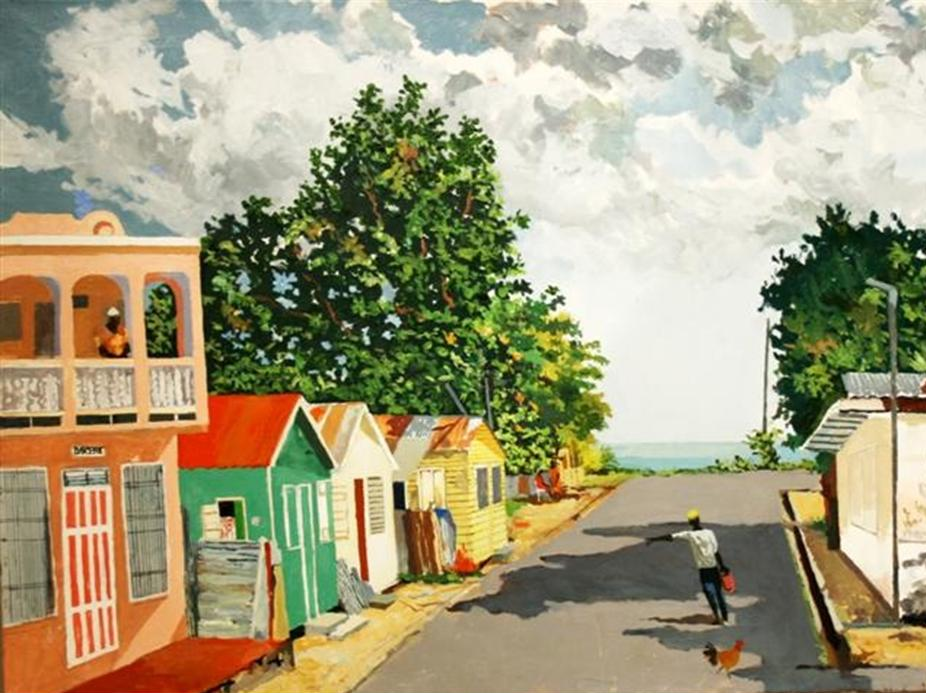

Derek Walcott (1930–2017) made clear that he was inspired by the epics of Homer with the very title of his long 1990 poem Omeros. However, Omeros is no simple translation of an ancient to a modern narrative: Walcott draws on the language, imagery, and themes of Homer, as well as Virgil’s Aeneid, to tell a story that is both new and age-old.

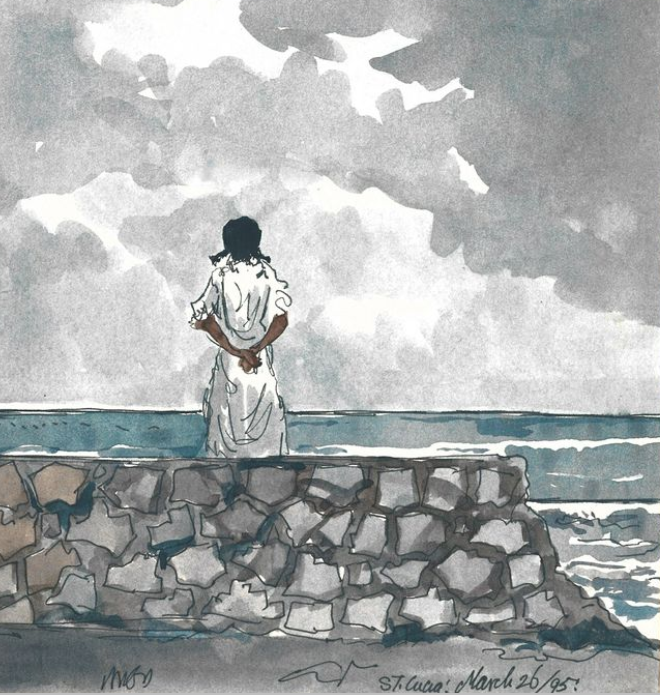

On the island of St Lucia, his characters struggle with conflicts of identity in a space whose history is coloured by colonisation and war. I will discuss these battles using Walcott’s description of his protagonist Achille’s attempt at nostos (“homecoming”), his depiction of Helen and the Homeric shadow, and his rejection of conventional epic form.

Raised in St Lucia within a Christian tradition, Walcott enjoyed a British-style education, and knew well the prominence of outside influences on his home country. A Methodist in an overwhelmingly Catholic region, he was educated from the age of thirteen at St Mary’s College, a Catholic school where he read widely, particularly in the works of the Irish writers William Butler Yeats and James Joyce.[1] In their verse and prose he found parallels to his own experience: “they were also colonials with the same kind of problems that existed in the Caribbean,”[2] he explained; and yet, they were not St Lucian. There was little study of Caribbean culture during his early education. The longing for a richer engagement with his surroundings is evident in his work.[3]

Walcott explores his own desires in the character of Achille, who journeys through time to a mythical Africa to talk to his father, Afolabe. The scene mirrors Odysseus’ journey down to Tartarus, as well as his encounter with his father Laertes in Book 24 of the Odyssey.

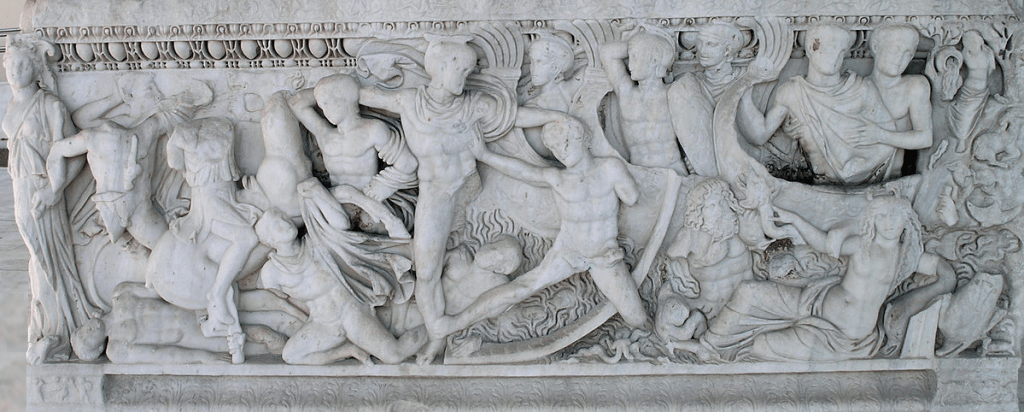

Walcott begins with a ritual to enter this metaphorical Underworld. As Achille sails farther from the shore of St Lucia, his thoughts turn to his fellow fishermen who have been lost at sea – “the nameless bones of all his brothers”.[4] This contrasts noticeably with what happens in Homer’s Odyssey: it is only after he consults the blind seer Tiresias, in accordance with instructions from the witch Circe, that Odysseus encounters his fallen comrades: Agamemnon (Hom. Od. 11.398), Achilles, Patroclus, Antilochus and Ajax (Od. 11.468–9).

Achille has no guide to help him revisit the dead. Walcott prepares us for Achille’s entry into the Underworld by first presenting both Achille and the reader with the souls of fishermen who have most recently died, before we meet Achille’s ancestors. His journey is more about revising the effects of history itself, rather than revisiting the dead.

Like Odysseus, Achille visits the dead to find answers, but while Odysseus seeks a way to return home, Achille wants to find a home in himself – to know “who he [is]”.[5] The scholar Line Henriksen thinks that this parallels, not Odysseus’ journey, but that of Telemachus early in the Odyssey when he sails to Pylos for news of his father,[6] Elements from both figures can be discerned in Achille as he searches for a father-land:

And here is my tamer of horses,

our only inheritance that elemental noise

of the windward, unbroken breakers, Ithaca’s

or Africa’s, all joining the ocean’s voice,

because this is the Atlantic now, this great design

of the triangular trade. Achille saw the ghost

of his father’s face shoot up at the end of the line. (Walcott (1990) 130)

Homer often refers to Hector as a “tamer of horses”; Walcott reminds the reader of a character for whom family is everything. Hector demonstrates love of his homeland through defending Troy; Odysseus does so through his persistent effort to return home.

After this revelation, Achille reaches “the end of the line”. This recalls Achille’s fishing line and ties it to the lines of poetry in which it is described, entwining his way of life with the poetic tradition which immortalised epic heroes. However, it also suggests a point of no farther progress, and the end of a line of descendants – Achille is the youngest of his line. There looms “his father’s face”. At the end of the discussion of his confused heritage, Achille’s only chance for “closure” is to reach the end of his epic.

Achille crosses the mangroves in his canoe, an image which recalls the crossing of the Styx in Book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid, as Aeneas journeys to seek his father Anchises. Rather than the mythical ferryman Charon, however, it is a “skeletal warrior” who journeys with him;[7] this warrior possibly belongs to an ancient African tribe. Walcott uses the image of the “piglet / find[ing] its favourite dug in the sweet-grunting sow” to underline the sense of prophesised homecoming, again echoing the Aeneid: Aeneas founds his city where he discovered a sow suckling her piglets (Aen. 8.84–5). Yet for Achille, this journey is not real. He must return home.

This suggestion of self-deception again arises in Achille’s meeting with his so-called father, Afolabe, who lived too long ago to be Achille’s real father. In the Aeneid, Anchises tells Aeneas all the wonderful future of his line (Aen. 6.757–859), and even demystifies the origin of life (726–52). There is no such comfort for Achille. When he introduces himself, Afolabe responds, “Achille. What does the name mean? I have forgotten the one that I gave you.” Achille admits, “I too have forgotten.”

Afolabe cannot overcome this. A meaningless name, he argues, makes a man nothing: “unless the sound means nothing. Then you would be nothing. Did they think you were nothing in that other kingdom?” The repetition of “nothing” here is uncomfortable, not only because we know the hurt Afolabe’s words cause Achille, but also because its echoes another journey. Odysseus’ famous “no man” (Outis) trick on Polyphemus’ island in Book 9 of the Odyssey is one Odysseus invents himself in order to escape death at the hands of the Cyclops.

Walcott shows us how Achille’s ancestral name was lost in Book 2, when a slave named Afolabe was renamed Achilles by the British Redcoats – there was a fashion for naming slaves after Classical figures.[8] “To keep things simple, [Afolabe] let himself be called [it].”[9] Martin McKinsey highlights the importance of the layers visible in the very name “Achille”:[10] the Greek Achilleus, transformed into the Roman Achilles, has become the French (and Creole) Achille. Afolabe cannot understand this name because he is not part of its history.

Walcott simultaneously associates with, and distances himself from, Achille:

Half of me was with him. One half with the midshipman

by a Dutch canal. But now, neither was happier

or unhappier than the other. (Walcott (1990) 135)

Walcott’s mixed-race heritage prevents him from identifying wholeheartedly with his African forebears.[11] However, by forcing him to come to terms with the complexity of his ‘St Lucianness’ over anything else, he finds peace in a way Achille fails to reach by the end of the poem. For Walcott, neither side of his heritage feels “happier / or unhappier than the other”.

An earlier poem, A Far Cry from Africa (1962) describes Walcott’s struggle as a mixed-race man: “where shall I turn, divided to the vein?” (l.27). This struggle continues in his narrator’s conflict with Omeros’ title character. He introduces Homer with this request: “O open this day with the conch’s moan, Omeros, / as you did in my boyhood, when I was a noun.”[12] The idea that Homer’s poetry colours all future artistic interactions from the moment he is first encountered is a central concern of Walcott’s poem, in which Homer becomes the very Muse he once called upon, immortalised as a modern-day literary god. But rather than calling on him for inspiration, Walcott looks back on a time when he was unable to draw Homeric parallels – “when [he] was a noun” and could exist purely as himself.

This literary shadow weighs particularly heavily on Walcott’s Helen. Walcott draws links between himself and another writer in the poem, the character Denis Plunkett, a retired Regimental Sergeant Major. Line Henriksen points out the similarity of “Denis Plunkett” to “Derek Walcott”, purely as a name.[13] Plunkett is engaged in writing the history of St Lucia, but his ideas become muddled by his attraction to Helen, a local beauty who works in his home.

The Major made his own flock of Vs, winged comments

in the margin when he found parallels. If she

hid in their net of myths, knotted entanglements

of figures and dates, she was not a fantasy

but a webbed connection, like that stupid pretence

that they did not fight for her face on a burning sea.

St Lucia was known as the Helen of the West Indies:[14] this was on account of its sheer attraction to Britain and France, who fought to colonise it from the 17th to the 19th century.[15] This obviously recalls the Trojan War: Walcott reinforces this notion by stating explicitly of the conflict Plunkett discusses: “Helen was its cause.” Then Plunkett’s thoughts drift to Helen the St Lucian, and he remembers the power she holds over him, as over countless others.[16]

Helen is almost entirely voiceless in Omeros, reduced to a face and a multitude of Homeric and biblical references. She is written about by Walcott and Plunkett and fought over by Hector and Achille, but, beyond these relations to other characters, she has little involvement in the poem’s narrative. Walcott writes:

Why not see Helen

as the sun saw her, with no Homeric shadow,

swinging her plastic sandals on that beach alone,

as fresh as the sea-wind? (Walcott (1990) 271)

Once more, Walcott demonstrates a desire to be free of the Homeric references which entangle his perception of the world, especially that of the poem’s only female character. The breezy, firmly modern image of Helen “swinging her plastic sandals” perfectly underlines why Homeric allusions can never sum up all that she is.

But the Homeric shadow persists. Walcott demonstrates the impossibility of throwing off his influence by referring to the sun, a concept prominent even in the poem’s initial invocation, in which he “open[s] the day”. We can never become the sun, only see by it; the sun casts a Homeric shadow, but we cannot see without it.

Several times during the poem, Walcott argues with Homer, first denying his significance and claiming “I never read it”.[17] Finally, however, he accepts Homeric influence. Walcott describes Omeros’ emergence from the sea, first as a European “marble head”, but then as the character Seven Seas, a native of St Lucia.[18]

Walcott acknowledges the differences between Homer and Seven Seas, comparing the Ancient Greek “chiton” and “marble” bust with the life of a fisherman in a “torn undershirt”. However, he also realises their similarities. Both have skins which “are preserved in salt”, and “accents born from a guttural shoal”, and vision “as wide as rain”.[19] This suggests the sheer scope of experience that can be encompassed by Homer’s storytelling. Modern St Lucians, like the characters of Homer, are never far from the shore.

In Seven Seas, Walcott creates his own Homer, with a face of “ebony hardness, skull and beard like cotton, its nose like a wedge.”[20] He reworks a traditional European Homer into a West Indian character, giving him dark skin and, significantly, a “beard like cotton” – this alludes to the island’s history of slavery. In making Homer look like the people of St Lucia, Walcott shows how his epics can be used to help tell their stories. The final resolution of this conflict comes in one of the few moments when Walcott’s terza rima stanzas dissolve into ordinary speech, and Omeros concludes: “A girl smells better than the world’s libraries.”[21]

Walcott famously denied Omeros’ status as an epic, but critics have persisted in calling it such since its publication.[22] We glimpse, in both his dialogue with the figure of Omeros in the poem and his treatment of characters themselves, something that he later clarified in a New York Times interview:

Epic makes people think of great wars and great warriors. That isn’t the Homer I was thinking of… One reason I don’t like talking about an epic is that I think it’s wrong to try to ennoble people… People are their own nouns.[23]

Here, Walcott recalls two key themes of Omeros itself: the importance, and beauty, of the everyday – as expressed in his choice of “a girl” over all “the world’s libraries” – and the wish for his characters to exist on their own terms, as “nouns” alone. Yet it was Walcott himself who chose to include these Classical allusions. Why draw our attention to so many outside influences if he wished for no such associations with his characters? How can we refrain from ennobling them?

Perhaps Walcott’s humanising of Homer’s characters can help us here. In the final pages of the poem, Walcott calls Achille “Achilles”, after he has returned from a successful fishing trip: “triumphant Achilles, / his hands gloved in blood”. [24] Unlike elsewhere in the poem, where Achille’s personality is largely characterised by his lack of similarity to his wrathful namesake, the two images align here. Yet he then becomes “aching Achilles”, performing an ordinary post-fishing cleansing, washing sand from his feet, and scraping scales off his hands. He removes the ennobling blood of war himself and his name returns to ‘Achille’, putting “the wedge of dolphin / that he’d saved for Helen in Hector’s rusty tin.”[25]

This final act of love, shadowed by a reference to his romantic rival, softens Achille as a man too practical to hold dramatic grudges. While, in Book Twenty-Four of the Iliad, Achilles’ act of mercy comes, after much petitioning, in the form of a truce to enable Hector’s funeral (Hom. Il. 24.679), Achille’s merciful gesture amounts to the unasked-for adoption of a rusty tin. Hector’s name ends both Iliad and Omeros, but while Homer’s lines raise his legacy with the kleos of his epithet – “so they buried prince Hector, tamer of horses” (Hom. Il. 24.804) – the legacy of Walcott’s Hector is a rusty tin.

Walcott does not try to write a modern Odyssey. Rather, he uses Homeric references self-consciously, exploring the way Homer’s work colours cultural interactions today. Some elements he explicitly rejects, including the imposition of contemporary European values onto his characters, and the grand warrior narrative of traditional epic. After a struggle, Walcott reclaims a modern, Caribbean Homer, who can bring the vitality of his work to St Lucia in a manner that is joyful, if complex. The Omeros of Book 7 never manages to show shadowless characters, lit from above by the sun: instead, Walcott has the moon, “like a slice of raw onion”,[26] shine down, and we are left in its new light.

Isabella Redmayne is a recent graduate in Classical Studies and English from The University of St Andrews, UK. She is interested in the politicisation of ancient stories in the modern day, and in the way ancient texts present conflicting truths. She is also a writer and has most recently been published in t’ART Press.

Further Reading

David Allison & Larrie Ferreiro, The American Revolution: A World War (Smithsonian Books, Washington, DC, 2018).

Jean Antoine-Dunne, Overtones of the Visual Imagination: Interlocking Basins of a Globe (Peepal Tree Press, Leeds, 2013).

Paul Breslin, Nobody’s Nation: Reading Derek Walcott (Univ. of Chicago Press, IL, 2001).

D.R.J. Bruckner, “The poet who fused folklore, Homer, and Hemingway,” New York Times, 9 Oct., 1990.

Line Henriksen, Ambition and Anxiety: Ezra Pound’s Cantos and Derek Walcott’s Omeros as Twentieth Century Epics (Cross Cultures, New York, 2006).

Edward Hirsch, “An interview with Derek Walcott,” Contemporary Literature 3 (1979), 288.

Charlotte McClure, “Helen of the West Indies: History or poetry of a Caribbean realm,” Studies in the Literary Imagination 26.2 (Autumn, 1993) 7–20.

Maria McGarrity, Allusions in Omeros: Notes and a Guide to Derek Walcott’s Masterpiece (Univ. Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 2015).

Martin McKinsey, “Missing sounds and mutable meanings: names in Derek Walcott’s Omeros,” Callaloo 31.3 (Summer, 2008) 891–902.

Derek Walcott, A Far Cry from Africa (1962), available here.

Derek Walcott, Omeros (Faber and Faber, London, 1990).

Derek Walcott, Sea Grapes (1992), available here.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Breslin (2001) 16. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Hirsch (1979) 288. |

| ⇧3 | Breslin (2001) 14–18. |

| ⇧4 | Walcott (1990) 128. |

| ⇧5 | Walcott (1990) 130. |

| ⇧6 | Henriksen (2006) 231. |

| ⇧7 | Walcott (1990) 133. |

| ⇧8 | Henriksen (2006) 236. |

| ⇧9 | Walcott (1990) 83. |

| ⇧10 | McKinsey (2008) 895. |

| ⇧11 | McGarrity (2015) 100. |

| ⇧12 | Walcott (1990) 12. |

| ⇧13 | Henriksen (2006) 244. |

| ⇧14 | McClure (1993) 7. |

| ⇧15 | Allison & Ferreiro (2018) 220. |

| ⇧16 | Walcott (1990) 96–7. |

| ⇧17 | Walcott (1990) 283. |

| ⇧18 | Walcott (1990) 280. |

| ⇧19 | Walcott (1990) 281. |

| ⇧20 | Ibid. |

| ⇧21 | Walcott (1990) 284. |

| ⇧22 | Henriksen (2006) 233. |

| ⇧23 | Bruckner (1990). |

| ⇧24 | Walcott (1990) 324. |

| ⇧25 | Walcott (1990) 325. |

| ⇧26 | Ibid. |