J.C. Wiles

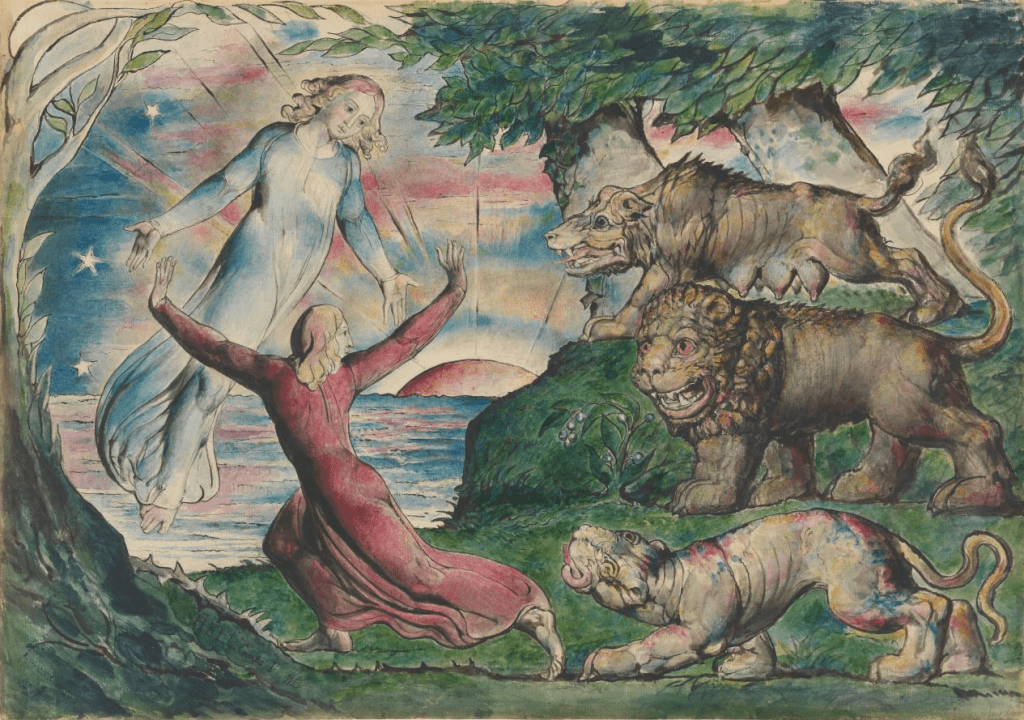

Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (1321) wears its Classical influences comfortably on its sleeve. Both Dante as author-of-the-poem and Dante as protagonist-of-the-narrative are shown to be heavily indebted to ancient – and especially Roman – literature, and this indebtedness to antiquity is dramatised even in its opening scene. Dante, who finds himself lost in a dark wood, is threatened by three beasts: a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf, and at the moment when all hope seems lost, he sees a shadowy figure to whom he calls out for help:

Mentre ch’i’rovinava in basso loco,

dinanzi a li occhi mi si fu offerto

chi per lungo silenzio parea fioco.

Quando vidi costui nel gran diserto,

“Miserere di me,” gridai a lui,

qual che tu sii, od ombra od omo certo!” (Inferno 1.61–6).

As I went, ruined, rushing to that low,

there had, before my eyes, been offered one

who seemed – long silent – to be faint and dry.

Seeing him near in that great wilderness,

to him I screamed my “Miserere”: “Save me,

whatever – shadow or truly man – you be.”[1]

The figure, who appears faint from long silence, is none other than Vergil, who becomes a key character in the poem’s narrative, acting as guide to Dante through the Christian Hell and Purgatory, before returning to Limbo – a place in Hell reserved for those who lived before Christ. Dante ascends to Paradise with a new guide, Beatrice, who had inspired the writing of Dante’s first book Vita nuova (“New Life”), and whose death was a fundamental event in the process of Dante’s poetic development, to the point that it also underpins the entire project of the Comedy.

Dante’s recognition of Vergil in the dark wood is run through with an equal recognition of the ancient poet as his greatest poetic influence:

“Or se’ tu quel Virgilio, e quella fonte

che spandi di parlar sì largo fiume?”

Rispuos’io lui con vergognosa fronte.

“O delli altri poeti onore e lume,

valgiami’l lungo studio e’l grande amore

che m’ha fatto cercar lo tuo volume.

Tu se’ lo mio maestro e’l mio autore;

tu se’ solo colui, da cu’io mi tolsi

lo bello stilo che m’ha fatto onore.” (Inferno 1.79–87).

“So, could it be,” I answered him (my brow,

in shy respect, bent low), “you are that Vergil,

whose words flow wide, a river running full?

You are the light and glory of all poets.

May this serve me: my ceaseless care, the love

so great, that’s made me search your writings through!

You are my teacher. You, my lord and law.

From you alone I took the fine-tuned style

that has, already, brought me so much honour.”

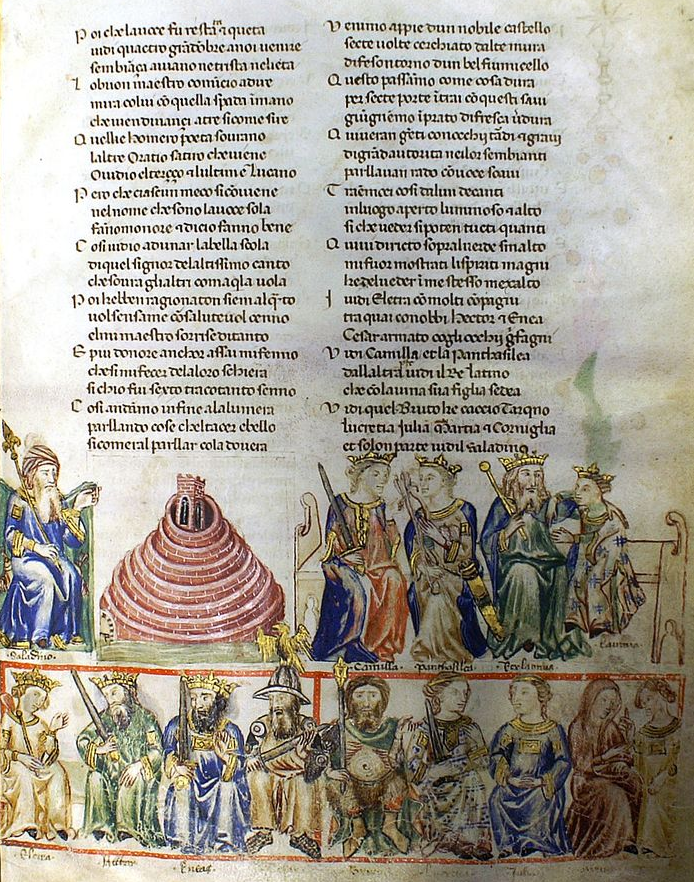

Despite Dante’s poetic indebtedness to Vergil, though, the choice of a Golden Age Latin poet as guide for two thirds of a journey though the Christian afterlife cannot but strike the reader as strange. We might more readily expect a figure like St Paul to guide Dante, given his experience making return trips to the afterlife. Dante will in fact acknowledge his own lack of credentials for journeying though the afterlife precisely though reference to Paul, as well as to Vergil’s own Aeneas: “Ma io, perché venirvi? o chi’l concede? Io non Enëa, io non Paolo sono” (“I’m not / your own Aeneas. I am not Saint Paul,” Inferno 2.32–3). Further, Vergil himself will soon reveal that his place in the afterlife is, in fact, in Hell, though he has not been sent there for any particular sin. Rather, he resides in Limbo: a place reserved for virtuous pagans who died before the time of Christ, as well as other groups of individuals, including unbaptised children.

The reasons that have been suggested for Dante’s choice of Vergil as his guide are many and various: he has been read as the embodiment of human reason, without which one cannot hope to attain salvation; he has been understood as personifying his own “tragic” poem, the Aeneid, such that he offers a consistent counterpoint to Dante’s construction of a Christian Comedy (one critic memorably calls Vergil the “tragedia nella Commedia”: the tragedy in the Comedy). Connectedly, it has been proposed that his presence allows Dante to reveal the limitations of Classical knowledge and literature in the context of a Christian journey, heightening the sense of the indispensability of Scripture and a knowledge of Christ to salvation.

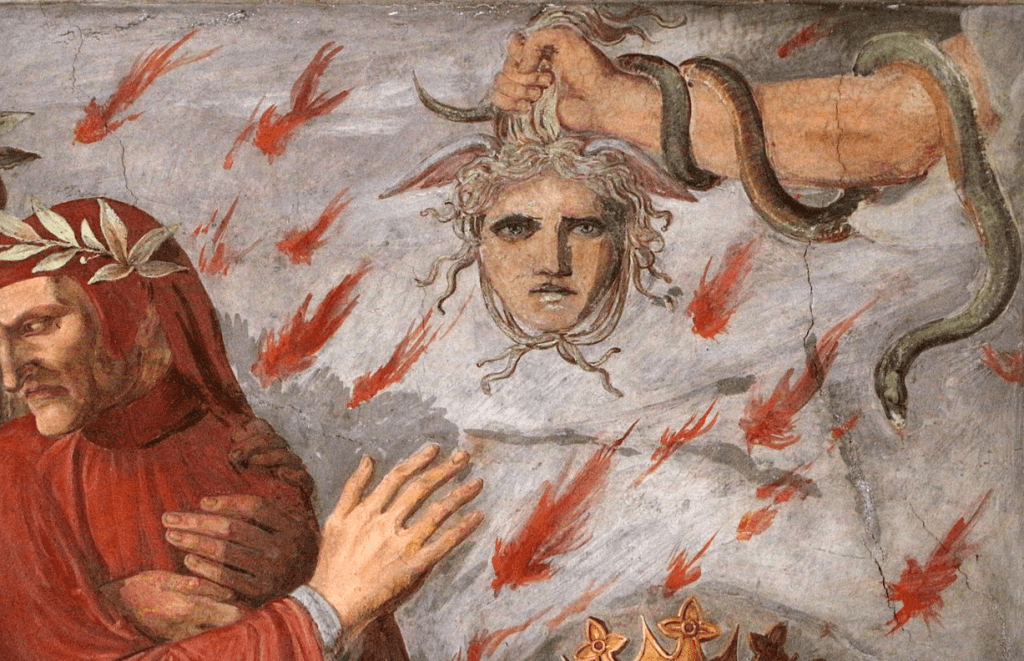

What unites these readings is their sense that he also seems to have been chosen precisely because he cannot take Dante all the way to the end of his journey. Dante establishes a deep personal connection between the two poets, and the closeness of their relationship is routinely foregrounded by reference to their literal proximity to one another. Indeed, it is a dynamic dramatised most overtly in moments of physical contact between them, which are strikingly frequent. To give just a few examples among many, as the poets attempt to enter the hellish City of Dis, they are accosted by the Furies, who call on Medusa to turn Dante to stone, whereupon Vergil takes hold of his charge and turns him away from the scene, covering Dante’s hands with his own in order to shield him from the Gorgon’s petrifying gaze:

“Volgiti’n dietro e tien lo viso chiuso;

ché se’l Gorgón si mostra e tu’l vedessi,

nulla sarebbe di tornar mai suso.”

Così disse’l maestro; ed elli stessi

mi volse, e non si tenne a le mie mani,

che con le sue ancor non mi chiudessi. (Inferno 9.55–60).

“Turn round! Your back to them! Your eyes tight shut!

For if the Gorgon shows and you catch sight,

there’ll be no way of ever getting out.”

He spoke and then, himself, he made me turn

and, not relying on my hands alone,

to shield my eyes he closed his own on mine.

In another more extreme case, Vergil will in fact take Dante onto his lap so they can slide down a rocky ridge to escape the Malebranche demons:

Lo duca mio di súbito mi prese,

come la madre ch’al romore è desta

e vede presso a sé le fiamme accese,

che prende il figlio e fugge e non s’arresta,

avendo piú di lui che di sé cura,

tanto che solo una camicia vesta. (Inferno 23.37–42)

My leader in an instant caught me up.

A mother, likewise, wakened by some noise,

who sees the flames – and sees them burning closer –

will snatch her son and flee and will not pause,

caring less keenly for herself than him,

to pull her shift or undershirt around her.

At the very bottom of Hell, Dante will even ride on Vergil’s back as the poets escape from Hell by traversing the body of Lucifer himself:

Com’a lui piacque, il collo li avvinghiai;

ed el prese di tempo e loco poste,

e quando l’ali fuoro aperte assai,

appigliò sé a le vellute coste;

di vello in vello giù discese poscia

tra’l folto pelo e le gelate croste. (Inferno 34.70–5).

As he desired, I clung around his neck.

With purpose, he selected time and place

and, when the wings had opened to the full,

he took a handhold on the furry sides,

and then, from tuft to tuft, he travelled down

between the shaggy pelt and frozen crust.

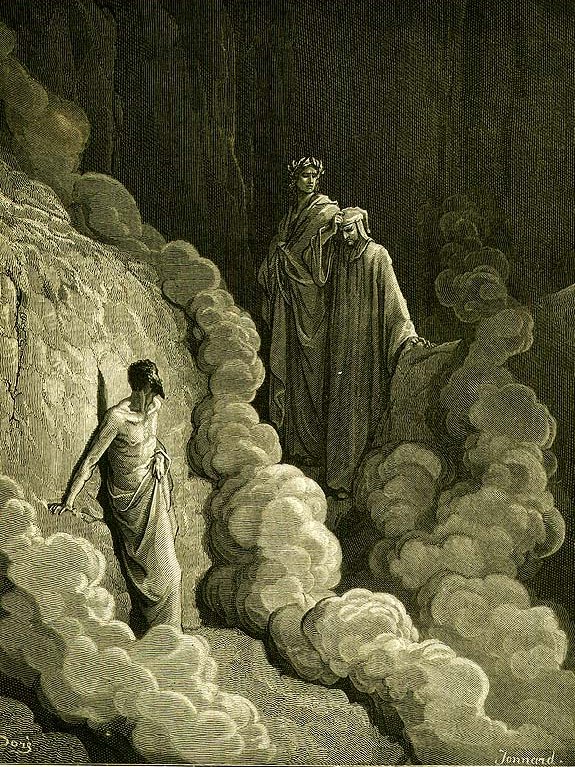

This emphasis on the haptic relationship between Dante and Vergil is particularly surprising given that the afterlife depicted in the Comedy is populated almost exclusively by “ombre vane” (shadows, empty) (Purgatorio 2.79). Interpersonal tangibility in the Comedy is highly variable: although Dante is unable to embrace his friend Casella in the second canto of Purgatorio, Vergil and the poet Sordello are able to embrace a few cantos later, while Vergil and his fellow Latin poet Statius are unable to do so near the end of the poets’ purgatorial journey. These recurring failed embraces themselves recast the moment in which Aeneas cannot embrace his father Anchises in Vergil’s own Aeneid (6.700–3), and reveal the strong affective underpinning that Vergil’s text provides, even in the context of a Christian narrative. Nevertheless, Dante never stages any kind of failed contact between the Comedy’s protagonist and his guide.

Indeed, as the above examples show, quite the opposite is true: Dante takes great pains to underscore Vergil as a significant personal presence in the first two thirds of the Comedy. Although there are certain cantos in which Vergil fades somewhat into the background – and this happens increasingly in Purgatorio, where his capacity to guide Dante is necessarily limited – we are always made highly aware of him as a dominant presence throughout Dante’s journey through Hell and Purgatory.

As the journey through the second realm progresses, though, the attentive reader will notice a subtle decline in references to physical contact between Dante and Vergil. Their last moment of contact is in fact given a great deal of structural privilege, occurring as it does in Purgatorio 16, at the structural centre of the Comedy. In the thick darkness which purges the sin of anger, Vergil invites Dante to hold on to him so as not to lose him:

… la scorta mia saputa e fida

mi s’accostò e l’omero m’offerse.

Sì come cieco va dietro sua guida

per non smarrirsi e per non dar di cozzo

in cosa che’l molesti, or forse ancida,

m’andava io per l’aere amaro e sozzo,

ascoltando il mio duca che diceva

pur: “Guarda che da me tu non sia mozzo” (Purgatorio 16.8–15).

… my guide, as ever wise and true,

came to my side, his shoulder lending aid.

And, as a blind man goes behind his guide –

for fear he’ll wander or collide with things

that might well main him or, perhaps, could kill –

I, too, went on through acrid, filthy air,

attending to my leader, who would say,

“Take care. Don’t get cut off!” repeatedly.

After this moment, there is no further physical contact between Dante and Vergil, and this absence of interpersonal contact foreshadows the moment in the Comedy where Vergil will disappear from Dante’s side altogether. At the top of the mountain of Purgatory, Dante arrives in the Garden of Eden, where he is reunited with Beatrice. When he finally senses her presence, Dante turns:

per dicere a Virgilio: “Men che dramma

di sangue m’è rimaso che non tremi:

conosco i segni de l’antica fiamma.”

Ma Virgilio n’avea lasciati scemi

di sé, Virgilio dolcissimo patre,

Virgilio a cui per mia salute die’mi;

né quantunque perdeo l’antica matre,

valse a le guance nette di rugiada

che, lagrimando, non tornasser atre. (Purgatorio 30.46–54)

To say to Vergil: “There is not one gram

of blood in me that does not tremble now.

I recognise the signs of ancient flame.”

But Vergil was not there. Our lack alone

was left where once he’d been. Vergil, dear sire,

Vergil – to him I’d run to save my soul.

Nor could the All our primal mother lost,

ensure my cheeks – which he once washed with dew –

should not again be sullied with dark tears.

As Dante prepares the poem’s great moment of reunion between Dante and Beatrice, that is to say, he stages the loss of his “dolcissimo patre”, who had rescued him from the dangers of the dark wood of Inferno 1, and guided him for almost two thirds of the way through the afterlife: having been by Dante’s side for 64 of the Comedy’s 100 cantos, Vergil is gone. Dante’s Eden thus becomes the backdrop for a double drama of presence and absence.

Even as they announce the departure of Vergil-as-character, however, these lines underscore the continuing intertextual presence of Vergil-as-poet. The lines that announce his departure are, as readers have frequently noted, movingly replete with Vergilian resonances: “conosco i segni de l’antica fiamma” is a direct translation of Dido’s “agnosco veteris vestigia flammae” (Aeneid 4.23), while the naming of “Virgilio” three times recalls Georgics 4, in which Orpheus calls Eurydice’s name three times at the moment of his death, having lost her irrevocably by turning back to look at her as they escaped from the Underworld.

The pathos generated by this choice to bid farewell to Vergil in such densely Vergilian language continues to beguile readers of the poem, and has recently been transposed onto the stage in Wayne McGregor’s ballet adaptation of the Comedy, The Dante Project. They also signal the ways in which Vergil’s role will continue in the poem despite his personal absence. Indeed, what Erich Auerbach calls the “Vergilian element” of the Comedy continues to underpin some of the most significant moments of Paradiso. When Dante encounters his ancestor, the crusader Cacciaguida, in the Heaven of Mars, their meeting is overtly framed in Vergilian terms:

Sì pïa l’ombra di’Anchise si porse,

se fede merta nostra maggior musa,

quando in Elisio del figlio s’accorse.

“O sanguis meus, o superinfusa

gratia Dei, sicut tibi cui

bis unquam celi ianüa reclusa?”

Così quel lume: ond’io m’attesi a lui. (Paradiso 15.25–31)

So, too, the shadow of Anchises showed

(if we give credence to our greatest muse),

seeing his son approach him in Elysium.

“O sanguis meus, o superinfusa

Gratia Dei, sicut tibi cui

bis unquam celi ianüa reclusa?”

The light spoke thus. I gave my mind to him.

Dante’s encounter with his distant ancestor is directly compared to the meeting between Aeneas and his father Anchises in the Elysian Fields in Aeneid 6. Further, as readers have noted since the Comedy’s first appearance, Cacciaguida’s “O sanguis meus” strongly recalls Anchises’ reference to Julius Caesar in same Vergilian episode (6.835). On the most superficial level, then, Dante’s allusions to the Aeneid serve to underscore the absence of its writer from the heavenly community of the final part of the Comedy.

On a deeper, more affective level, we might also note here the recurrence of the language of paternity, which was so frequently applied to Vergil himself throughout the course of his journey alongside Dante, and especially at the moment of his departure in Purgatorio 30. In a canto of the Comedy which is so deeply concerned with questions of ancestry, it is perhaps no wonder that Dante should recall the Comedy’s own “dolcissimo patre” – even if only through intertextual reference.

It is, moreover, not just Vergil’s poetic language and texts that remain important in Paradiso. Of course, just as it is important to distinguish between Dante-as-poet and Dante-as-protagonist, it is also necessary to separate Vergil-as-character from the historical Vergil in the Comedy: intertextual “presence” is not necessarily coterminous with the narrative presence of a character. Nevertheless, Dante consistently makes use of both forms of allusion in Paradiso to remind us of the personal absence of his former guide. During the same encounter with Cacciaguida, Vergil’s absence as a character is brought strongly to the fore. As his ancestor moves towards prophesying Dante’s imminent exile, he explains:

… mentre ch’io era a Virgilio congiunto

su per lo monte che l’anime cura

e discendendo nel mondo defunto,

dette mi fuor di mia vita futura

parole gravi, avvegna ch’io mi senta

ben tetragono ai colpi di ventura. (Paradiso 17.19–24)

While I was still in Vergil’s company

climbing the hill that remedies our souls,

so, too, descending to the dead, waste world,

he spoke to me in grave and weighty words

about my future, so I should feel

four-square against the blows that were to come.

Each time Dante-as-poet invokes Vergil either as an intertext or as a character, we cannot but feel the lack Dante-as-character experiences following Vergil’s departure from the poem’s narrative in Purgatorio 30. Indeed, given the way in which personal absence and intertextual presence are bound together in the passage which marks Vergil’s disappearance, it becomes all but impossible to separate the two, even in the highest reaches of Paradiso. On the contrary, Vergil, despite his personal absence, remains vital to Dante’s journey up until its final moments. As he attempts to articulate the experience of witnessing God in the final canto of Paradiso, he communicates the insufficiency of his senses by once again making recourse to the Aeneid:

Così la neve al sol si disigilla;

così al vento ne le foglie levi

si perdea la sentenza di Sibilla. (Paradiso 33.64–6)

So, too, snow will lose its seal.

So, too, the oracles the Sibyl wrote

on weightless leaves are lost upon the wind.

As the Comedy begins to draw to a close, its vision of God scatters like the prophetic leaves of the Cumaean Sibyl, whose prophecies are carried away by the wind. Even as the Comedy reaches the apotheosis of its Christian vision, then, it reaches back to Vergil’s pagan epic. The pre-Christian “volume” from which Dante drew his style aids him, ultimately, in figuring his poem’s final vision, and as it does so, the “maestro” and “autore” who wrote it is once again brought clearly into view. The Comedy’s protagonist may lose Vergil, but its author, from first to last, never does.

J.C. Wiles is a PhD canditate in Italian studies at Selwyn College, Cambridge, where he holds a Jebb Studentship. His research focuses on representations of absence in Dante’s Divine Comedy, and he has previously written on Giovanni Boccaccio, Anna Maria Ortese, Virginia Woolf, and the modern Italian lyric. His poetry pamphlet, love and/or the storm, was published by Broken Sleep Books in 2020, and his translation of the work of three contemporary Italian poets, Giuseppe Garofalo, Francesca Matteoni, and Beatrice Sica, was recently anthologised in Alibi: Prima antologia bilingue di poesia italiana nel Regno Unito. He is also an associate director of the Chronicle Theatre Company, which runs outreach programmes on Shakespeare between the UK and Italy.

Further Reading

Erich Auerbach, Dante, Poet of the Secular World (tr. Ralph Manheim) (Chicago UP, IL, 1961; first publ. 1929).

Teodolinda Barolini, Dante’s Poets: Textuality and Truth in the Comedy (Princeton UP, NJ, 1984).

Robert Hollander, Il Virgilio dantesco: tragedia nella ‘Commedia’ (tr. Anna Maria Castellini) (Leo S. Olschki, Florence, 1983).

Lloyd H. Howard, Virgil the Blind Guide: Marking the Way Through the Divine Comedy (McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal, 2010).

Rachel Jacoff & Jeffrey T. Schnapp (edd.), The Poetry of Allusion, Virgil and Ovid in Dante’s Commedia, (Stanford UP, CA, 1991).

Heather Webb, Dante, Artist of Gesture (Oxford UP, 2022).

Winthrop Wetherbee, The Ancient Flame: Dante and the Poets (University of Notre Dame Press, IN, 2008).

Notes

| ⇧1 | All Italian quotations from the Commedia are cited from A.M. Chiavacci Leonardi (ed.), Dante: Commedia (Mondadori, 1991–4, 3 vols). All translations are Robin Kirkpatrick’s, as found in his Dante: The Divine Comedy (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 2006–7). All other Italian translations are my own. |

|---|