Mateusz Stróżyński

The third instalment of a trilogy on the New Testament this Easter.

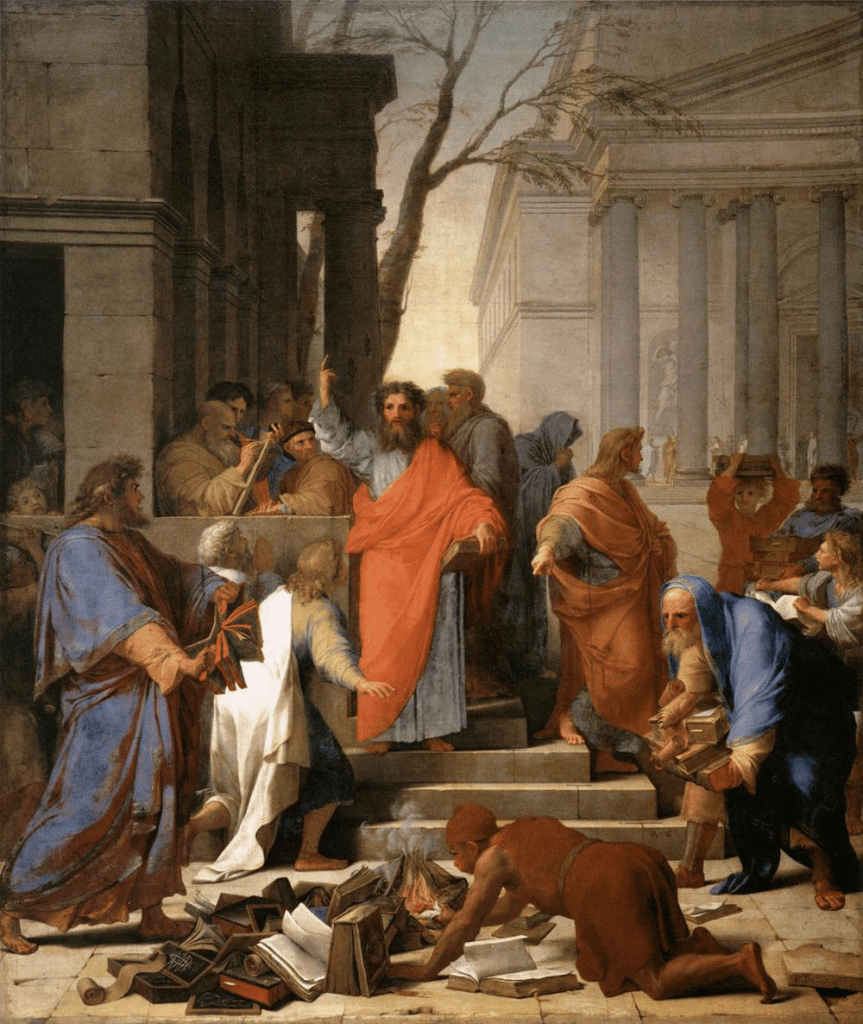

Plato’s famous Allegory of the Cave, at the beginning of Book 7 of the Republic, ends violently. The second part of the narrative focuses on a man who, for some mysterious reason, is liberated from his chains, and is thus enabled to leave the Cave, and see the real world bathed in sunlight. Then, moved by compassion, he comes down to the Cave again; but his attempts at freeing his fellow prisoners fail entirely.

They start to mock his inability to explain the precise nature of the shadows on the walls of the cave: these are the only reality they know. He tries in vain to make them understand the shadows’ exact relation to reality. The entire misunderstanding results from one man’s solitary transition from the Cave’s darkness to sunlight, and then back from light to the darkness again, and the impact these transitions have had on the sight of the one who has moved between the two worlds, and is unaccustomed to the experience. The whole affair begins in mockery and disdain, but ends in murder.

Socrates says:

καὶ τὸν ἐπιχειροῦντα λύειν τε καὶ ἀνάγειν, εἴ πως ἐν ταῖς χερσὶ δύναιντο λαβεῖν καὶ ἀποκτείνειν, ἀποκτεινύναι ἄν;

σφόδρα γ᾿, ἔφη.

“And if it were possible to lay hands on and to kill the man who tried to release them and lead them up, would they not kill him?”

“They certainly would,” [Glaucon] said. (Rep. 2.517a)

This is foreshadowed in Book 2 of the Republic, when Glaucon (historically speaking, Plato’s older brother), describes two perfect, personified models of injustice and justice. The purpose of those models is to show that people have mixed motivations: sometimes they behave justly, not because they believe it’s the right thing to do, but because the appearance of justice brings many social advantages. The true nature of one’s soul would be revealed, Glaucon argues, only if someone could wear the legendary ring of Gyges, which makes its bearer invisible, and thus allows him to escape all social consequences of his actions.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s One Ring, and the effect it has on its bearer’s soul, is in many ways similar to Plato’s ring of Gyges. In the Lord of the Rings it is often emphasised that even the most virtuous and morally good characters would be eventually corrupted by wearing the One Ring. The only character in Tolkien’s novel who seems to be immune to the influence of the Ring is the mysterious Tom Bombadil, the child-like singing and dancing fellow who, tellingly, is not depicted as someone interested in the common good of the peoples of the Middle Earth. He may be perfectly just in himself, but he’s not willing to sacrifice himself for the sake of others. Effectively, there is no-one among the races of Tolkien’s Middle Earth who would embody the perfectly Just Man as Glaucon envisions him.

Glaucon claims that the Unjust Man – who seems in many ways to resemble the figure of the tyrant described later on, in Books 8 and 9 – should be considered by everyone to be the most just, because only then would he not be motivated by any desire to please others or avoid their criticism: he would act purely out of his inner self. By contrast, the Just Man should appear to be the worst of all, such that he too would make all his decisions regardless of any desire for possible social benefits. Plato claims that the Just Man must be eventually killed:

ὁ δίκαιος μαστιγώσεται, στρεβλώσεται, δεδήσεται, ἐκκαυθήσεται τὠφθαλμώ, τελευτῶν πάντα κακὰ παθὼν ἀνασχινδυλευθήσεται καὶ γνώσεται ὅτι οὐκ εἶναι δίκαιον ἀλλὰ δοκεῖν δεῖ ἐθέλειν.

The just man will have to endure the lash, the rack, chains, the branding-iron in his eyes, and finally, after every extremity of suffering, he will be crucified, and so will learn his lesson that not to be just, but to seem just, is what we ought to desire. (Rep. 2.361e–362a)

It seems obvious that on some level Plato has in mind his own master, Socrates. As David Schindler has argued in Plato’s Critique of Impure Reason, the literary figure of Socrates in the Republic is key to its meaning.[1] While Schindler emphasises that Socrates embodies the Good, we can add that he also embodies the Just Man of Book 2. The whole dialogue begins with a “coming down” of Socrates to the Piraeus (κατέβην χθὲς εἰς Πειραιᾶ, Rep. 1.327a), symbolising the compassionate descent of a liberated prisoner to the Cave, as described in Book 7.

Christian authors from antiquity to early modernity often saw in this Plato’s prophecy of the torture and death of the truly Just One, the God-Man Jesus Christ. Also, in the biblical Book of Wisdom (chapter 2), which was written in Greek, probably within a community of Hellenised Jews in the 2nd century BC, there are fairly clear allusions to the murder of the Just Man in Plato’s Republic:

-

- Therefore let us lie in wait for the righteous (dikaion); because he is not for our turn, and he is clean contrary to our doings: he upbraideth us with our offending the law, and objecteth to our infamy the transgressings of our education.

- He professeth to have the knowledge of God: and he calleth himself the child of the Lord.

- He was made to reprove our thoughts.

- He is grievous unto us even to behold: for his life is not like other men’s, his ways are of another fashion.

- We are esteemed of him as counterfeits: he abstaineth from our ways as from filthiness: he pronounceth the end of the just to be blessed, and maketh his boast that God is his father.

- Let us see if his words be true: and let us prove what shall happen in the end of him.

- For if the just man (dikaios) be the son of God, he will help him, and deliver him from the hand of his enemies.

- Let us examine him with despitefulness and torture, that we may know his meekness, and prove his patience.

- Let us condemn him with a shameful death: for by his own saying he shall be respected.

- Such things they did imagine, and were deceived: for their own wickedness hath blinded them.[2]

Already the Hellenised Jews of that period saw a correspondence between the Jewish idea of the Just One or the Righteous One, and Plato’s perfect dikaios from the Republic. In the Book of Genesis, there occurs the story of Abraham’s bargain with God over the intended destruction of Sodom, in which God promises to spare that sinful city, if ten just men can be found there (Gen 18:20–33). However, only one just man, Lot, Abraham’s relative, is found in Sodom, so the city is destroyed.

We have to remember, of course, that in the Psalms, as well as in other books of Jewish Scripture, it is God who is primarily the Just One: a man is called thus only secondarily, if he is obedient to God. That foreshadows, in many ways, the doctrine of the image of God (based on Gen 1:26) and of participation and divinisation, developed within late-antique Christian Platonism. In the so-called Deutero-Isaiah, that is, the part of the Book of Isaiah written most probably towards the end of the 6th century BC (chapters 40–55), the Just Man is a special servant of God, who will take upon himself the sins of his people: by virtue of that, he will save them.

The famous chapter 53 of the Book of Isaiah was understood by Christians as one of the most precise Old Testament prophecies of Christ’s Passion:

-

- He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

- Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.

- But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.

- All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all.

- He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth: he is brought as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth.

- He was taken from prison and from judgment: and who shall declare his generation? for he was cut off out of the land of the living: for the transgression of my people was he stricken.

- And he made his grave with the wicked, and with the rich in his death; because he had done no violence, neither was any deceit in his mouth.

This Suffering Servant is called explicitly “the Just Man” in the Greek translation of the Bible, the Septuagint: “the Just Man (dikaios), who is a good servant, will justify (dikaiōsai) many” (δικαιῶσαι δίκαιον εὖ δουλεύοντα πολλοῖς, Is 53:11).

It seems that the author of the Book of Wisdom merges the Deutero-Isaiah account with Plato’s Just Man, implying that it is not just the wickedness of men, but also God’s will, that the Just Man should suffer and die a horrible death. Naturally, Christians understood both the Suffering Servant of Deutero-Isaiah and the entire Jewish tradition of the Just Man (including Wisdom 2) as an image of the God-Man.

St Paul may have had the “the Just Man, who is a good servant” (eu douleuonta), in mind, when he was writing his great hymn (Phil 2:5–11), in which Incarnation is described as becoming a servant or a slave (doulos). As we have seen, the essential element of Plato’s Just Man is stripping off all the appearance of justice. For St Paul, it’s also crucial that the God-Man gives away all the appearance not only of justice, but also of His divine nature. He undergoes kenōsis, “emptying out”, “denudation”, or “annihilation”, hiding His justice under the cloak of injustice and humiliation, much like Plato’s Just Man:

- Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God:

- But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men:

- And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross. (Phil 2:6–8)

Again, St Paul is alluding to Isaiah 53, emphasising not only the status of the slave and the absolute obedience of the Just Man, but also the disgrace and humiliation that He suffers. The same idea appears in his Second Letter to the Corinthians: “For he [God] hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him” (2 Cor 5:21). The God-Man is made sin (hamartiā), which is equivalent, of course, to injustice, in order to make us the justice (dikaiosunē) of God.

We don’t have any proof, but it’s not impossible that St Paul was directly familiar with Plato’s Republic, since in his speech to Greek philosophers in Athens (Acts 17:28) he quotes phrases from other ancient philosophical sources: “For in him we live, and move, and have our being”, attributed to Epimenides of Crete (6th century BC), and “For we are also his offspring”, the words of Aratus of Soloi (315/310–240 BC), Phaenomena 5. The German Lutheran theologian Joachim Ringleben suggests even that Phil 2:6–11 was influenced by the Tenth Nemean Ode of Pindar (c.518–c.438 BC) and its rendering of the myth of Castor and Polydeuces.[3]

Throughout the entire New Testament, Christ is depicted as the only true Just Man. In the Gospel of Matthew, Pilate’s wife uses the word dikaios, when she tells him her dream: “Have thou nothing to do with that just man (dikaios): for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of him” (Mt 27:19). After Christ breathes His last breath, a centurion standing under the cross says: “Certainly this was a righteous man (dikaios)” (Luke 23:47). In the First Letter of Peter we read: “For Christ also hath once suffered for sins, the just for the unjust (dikaios huper adikon), that he might bring us to God” (1 P 3:18). The Second Letter of Peter interprets Lot as an image of Christ: “For that righteous man (dikaios) dwelling among them [sc. in Sodom], in seeing and hearing, vexed his righteous soul from day to day with their unlawful deeds” (2 P 2:8). And I have already emphasised the role of that motif in St Paul’s letters (see also Rom 1:17, 3:4, 3:26, 5:18–19; Heb 10:38, 11:4).

But was Plato, like the author of Deutero-Isaiah, prophesying the Passion of Christ, centuries before it happened? Secular historians and Classicists today will probably disparage such ideas as fantastic. Even St Jerome (AD c.347–c.420) wasn’t convinced of the widespread belief that Vergil’s Fourth Eclogue was a similar case of a prophecy uttered unconsciously by a Pagan, branding such interpretations “childish” (puerilia).[4] However, Joseph Ratzinger (1927–2022), Pope Benedict XVI, whose theology was deeply rooted in the ancient Church Fathers, revived this allegedly fantastic idea in his Introduction to Christianity (II.1.c), when he said the following about the Just Man passage in the Republic:

The Cross is revelation. It reveals, not any particular thing, but God and man. It reveals who God is and in what way man is. There is a curious presentiment of this situation in Greek philosophy: Plato’s image of the crucified “just man”… This passage, written four hundred years before Christ, is always bound to move a Christian deeply. Serious philosophical thinking here surmises that the completely just man in this world must be the crucified just man; something is sensed of that revelation of man which comes to pass on the Cross.

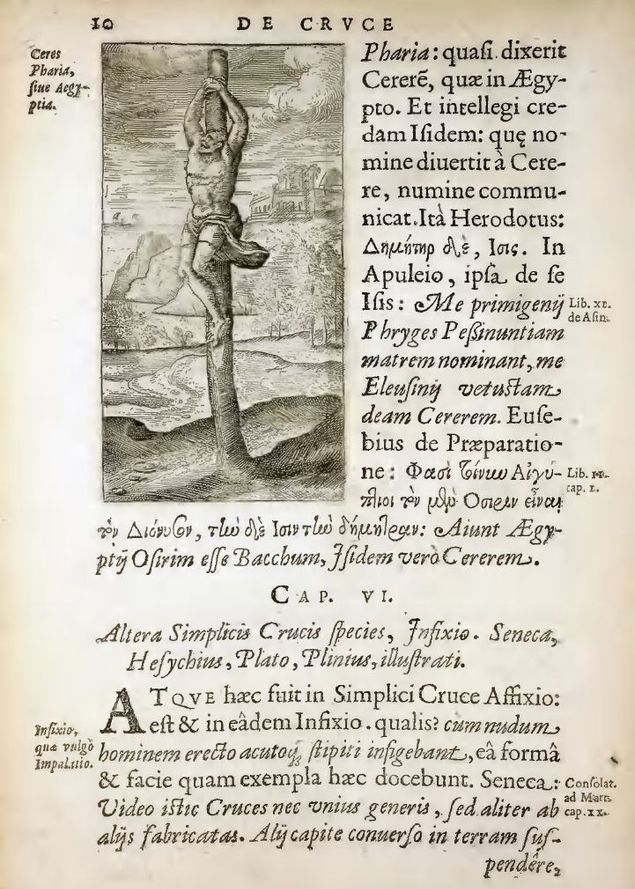

There is, however, an interesting detail concerning the translation of this passage from the Republic to be mentioned in this context. The 1892 English translation of Benjamin Jowett, the Oxford scholar and cleric, renders ἀνασχινδυλευθήσεται (anaschinduleuthēsetai) in 362a as “impaled”, as did the edition of F.M. Cornford (1941) and the translation of G.M.A. Grube (1974). Robin Waterfield (1993) and Chris Emlyn-Jones (2007) give the more precise “impaled on a stake”, but the latter, in his commentary, has literally not a word to say on this word’s meaning at 362a. As for Joe Sachs (2006), for some reason he translates it as “hacked in pieces”.

By contrast, Paul Shorey in the 1935 Loeb edition quoted above translated ἀνασχινδυλευθήσεται as “will be crucified”; but this remains a minority interpretation. Shorey adds in a footnote:

“Or strictly ‘impaled’. Cf. Cicero De Rep. 3.27. Writers on Plato and Christianity have often compared the fate of Plato’s just man with the crucifixion.”

The reference to Cicero’s Republic (a work preserved to us only in fragments) is interesting, but not very enlightening, since Cicero simply omits in his translation or paraphrase this problematic (or prophetic…) word: bonus ille vir vexetur, rapiatur, manus ei denique adferantur, effodiantur oculi, damnetur, vinciatur, uratur, exterminetur… Shorey doesn’t give any reason for choosing “crucified” instead of the more “strict” (as he puts it) “impaled”. The only two other instances of “crucified” known to me in this context are found in the translations of Desmond Lee (1955), and the famous American conservative thinker Allan Bloom (1968), author of The Closing of the American Mind (1987).

In other languages the situation is very similar, if not quite the same. The French 19th-century philosopher Victor Cousin (1792–1867) translated the word as “mis en croix” (1834). This interpretation was repeated more than hundred years later by Robert Baccou (1938), while the translation of Émile Chambry for the ‘Belles Lettres’ edition has the majority sense: “il sera empalé” (1932). In an early-modern Italian translation, Dardi Bembo used “impiccato” (“hanged”, at the turn of the 17th century). Ruggero Bonghi translates “impalato” (1849), just like Franco Sartori (1966) and Francesco Gabrieli (1981) after him. The 1990s translations of Mario Vitali and Mario Vegetti also use the equivalent of “impaled”. The only Italian translator who used “crocifisso” was the great historian of ancient philosophy, Giovanni Reale (1931–2014), who was a prominent Catholic intellectual.[5] In all three existing Polish translations, in Antoni Bronikowski’s (1866), Stanisław Lisiecki’s (1928), and the most recent translation of the Republic by Władysław Witwicki, there is the equivalent of “impaled”. The manuscript of Witwicki’s version miraculously survived World War II, hidden in a cellar while Warsaw was being systematically razed to the ground by the Germans in the summer of 1944, and was published in 1948.

When we consult the Greek Lexicon of Liddell-Scott-Jones (1843, last revised in 1940), “ἀνασχινδυλεύω” is identified with “ἀνασκολοπίζω”. The latter is defined in LSJ as “fix on a pole or stake, impale”. In the most recent Cambridge Greek Lexicon (2021), “ἀνασχινδυλεύομαι” is defined as “be impaled” (with explicit reference to Plato 362a), while “ἀνασκολοπίζω” is to “put on a stake, impale”, without any reference to crucifixion or any ambiguity of meaning. In Franco Montanari’s Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (2015), “ἀνασχινδυλεύω” is “to impale” (with a reference to 362a), while “ἀνασκολοπίζω” is given a broader meaning: “to hoist on a stake, impale, crucify”, but without linking it to “ἀνασχινδυλεύω”. Finally, Benselers Griechisch-Deutsches Wörterbuch (A. Kaegi ed., 1911) defines “ἀνασχινδυλεύω” similarly to LSJ: “aufpfählen, kreuzigen” (“to impale, to crucify”).

The reason that older dictionaries, like LSJ or Benselers, give both “impale” and “crucify”, seems to come from the use of the word in Herodotus. The father of history refers to a cruel Persian execution method consisting of thrusting a pole in someone’s groin (although Persians had developed several other methods of impalement as well). In Hist. 1.128, this is how Astyages punishes the Magi who persuaded him to let Cyrus go; in 3.159, Darius executes 3,000 men in Babylon in this manner after the city is captured (see also 3.122 and 4.43).

In one curious passage (9.78), Herodotus uses “ἀνασταυρόω”, which definitely means “to crucify” since stauros is a cross, to describe something which is not a crucifixion, but an impalement. After the battle of Thermopylae (480 BC), in which the Spartan king Leonidas died, Mardonius and Xerxes had their heads cut off and set upon poles, but here Herodotus says: “ἀνεσταύρωσαν” (“crucified”), although there was no cross in any sense of the word. This seems to suggest that the three terms “ἀνασχινδυλεύω”, “ἀνασκολοπίζω” and “ἀνασταυρόω” could have already been interchangeable with each other, even in Plato’s time.

Certainly this becomes the case in later Greek, as with Lucian of Samosata, who wrote in the 2nd century AD. In his Peregrinus (Foreigner), Lucian refers to Jesus of Nazareth as τὸν ἄνθρωπον τὸν ἐν τῇ Παλαιστίνῃ ἀνασκολοπισθέντα. (Peregr. 11). Two chapters later he says that Christians worship τὸν δὲ ἀνεσκολοπισμένον ἐκεῖνον σοφιστὴν (Peregr. 13). Despite the use of the verb ἀνασκολοπίζω (anaskolopizō), it would be absurd to translate these expressions, respectively, as “that man who was impaled in Palestine” and “that impaled sophist”, since all the sources we have agree that Christ was not impaled on a stake, but crucified in the Roman manner. However, in his Prometheus, Lucian has the titular Titan describe his own punishment on the Caucasus rock using exactly the same word, even though Prometheus was chained to a rock and not hanged on a cross or hoisted on a stake.

So what about the Just Man in the Republic? Was he impaled or crucified? In Classical Athens, where Plato grew up and where Socrates died, there were two common ways of executing criminals.[6] The first one was by hemlock and this was considered, as Jan Kucharski points out, almost a “luxury”, not the least because of the cost of a sufficient dose of the poison. This is the way Socrates died, as described by Plato (who didn’t witness it) at the end of the Phaedo. A much more painful way was a “bloodless crucifixion” or “ἀποτυμπανισμός” (apotumpanismos), as confirmed by archeological findings: “the convict is fastened to a wooden board and left to die of exposure, a feast for crows. The term ‘crucifixion’ may however be misleading, as the victim most likely had his hands bound alongside his body”.[7]

When Plato was writing his Republic, he obviously wasn’t familiar with the later Roman practice of crucifigere, which Christ suffered, although there were some variations on that cruel punishment in Roman times as well. Impalement must have been associated by Plato (as by other Athenians of the period) with the barbaric cruelty of the Persians. We can assume that Plato was imagining his Just Man living among the Greeks, not among Persians, who would really “impale” him. The final fate that the Just Man would undergo – “ἀνασχινδυλευθήσεται” – which was to cause his death, must have been for Plato the “bloodless crucifixion” of ἀποτυμπανισμός as described above. The story of Leonidas’ “crucified” head shows that the punishment was about public exposure and humiliation, not just slow torture. Plato’s Just Man, after being condemned of every possible crime, will be publicly displayed as the worst of criminals, even though he is the only one who is truly innocent.

How then should we translate this problematic word? Both “impaled” and “crucified” are misleading for a modern reader unfamiliar with ancient history, since the first suggests thrusting a long stake into someone’s body, while the second denotes the crucifixion familiar from Christian iconography, with the condemned man’s hands and feet nailed to a cross consisting of two beams (the vertical stipes, and the horizontal patibulum). Plato didn’t imagine either of these two but was most probably thinking of the Athenian capital punishment outlined above.

In that case, the translator has to make a choice, whether to make an allusion to the prophetic dimension of Plato’s Just Man as recognised by the Christian tradition, or to avoid that allusion entirely. It seems to be a curious situation, not unlike the one where a crucifix is taken from the wall of a classroom or some other public institution in a formerly Christian country, after having been on public display for a long time. It’s a situation still to be encountered in Poland, where there is a crucifix, not only in some classrooms but even in the Plenary Hall of the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish Parliament).

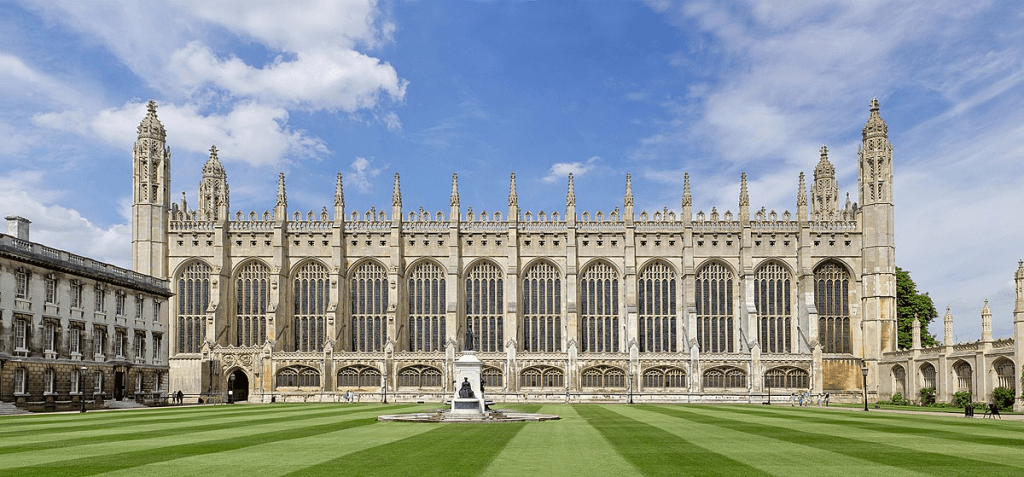

The explanation most often deployed for removing public crucifixes is that such a removal is an act of neutrality, inclusion or some (usually mythologised) “separation of church and state” (as Thomas Jefferson famously put it). Yet this is a thoroughly mistaken argument, in my view, because the very act of removing such a meaningful symbol, especially when it has occupied a central position for centuries, is about as “neutral” as destroying King’s College in Cambridge, or toppling a public statue of Churchill, would be for the British. To let the crucifix remain is, of course, a momentous decision too. In any case, there is no question of neutrality here.

If we translate “impale”, especially in our current culture, which strengthens itself by continually “removing crucifixes”,[8] we deny any Christian dimension to the symbolic figure of the Just Man in Plato. If, on the other hand, we use “crucified”, we acknowledge the existence of that dimension, whether we accept the truth of it or not.

The entire Gospel of John features Platonic patterns of descent and ascent, of the incarnated Logos coming down from the Father, from heaven, and returning to the Father, ascending back to heaven. This is surely similar to the descending and ascending movements in the Republic; Benedict XVI compares this structure of the Gospel of John to Plotinus’ metaphysics of descent and ascent.[9] Also, what Christ says about His mission in the third chapter of that Gospel resonates with Plato’s reference to the murder of the Just Man in the Allegory of the Cave: he was killed because he wanted to show his fellowmen the true light. Christ says of Himself:

And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. For every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved. But he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God. (John 3:19–21).

Plato asked, over three centuries earlier: “And if it were possible to lay hands on and to kill the man who tried to release them and lead them up, would they not kill him?” “They certainly would”, he said:

And eventually, some believe, they really did.

The two other articles in this trilogy can be read here and here.

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His new book Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World is forthcoming through Cambridge University Press.

Notes

| ⇧1 | D.C. Schindler, Plato’s Critique of Impure Reason: On Goodness and Truth in the Republic (Catholic Univ. of America Press, Washington, DC, 2008). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | This and all other quotations from the Bible are taken from the King James Version. |

| ⇧3 | J. Ringleben, “Pindar’s Celebration of Peace”, Ars Disputandi 2.1 (2002) 172–80. The article is available here. |

| ⇧4 | St Jerome, Ep. 53.7. On the Christian interpretations of Vergil, see E. Bourne, “The Messianic Prophecy in Vergil’s Fourth Eclogue,” Classical Journal 11, 7 (1916) 390–400, available here. |

| ⇧5 | I am grateful to Carlo Bonifacio for his assistance in surveying Italian translations of the Republic. |

| ⇧6 | J. Kucharski, “Capital Punishment in Classical Athens,” Scripta Classica 12 (2015) 13–28, available here. |

| ⇧7 | Kucharski, loc. cit., 26. |

| ⇧8 | See Charles Taylor’s description of the “parasitic” nature of the radical Enlightenment in his Sources of the Self (1989). |

| ⇧9 | J. Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth, Part 2: Holy Week: from the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection (Ignatius Press, San Francisco, CA, 2011) 54–61. |