D.S. Raven

This being the brave new world, the Antigone inbox receives many requests for help from students and enthusiasts (and occasionally academic colleagues) on matters relating to the Classical world. Sometimes we are asked for factual information, or for bibliographical recommendations. It is also not unusual for someone to send us some Latin or Greek text and ask what it means: they can translate it but are not sure what it all adds up to. The professional have chosen to call the close reading of, and thinking about, texts “practical criticism”. If this means that critical approaches to texts offer some practical benefit to readers of the text, all to the good; if not, perhaps it will be salutary to share with the world the wise advice of D.S. Raven – whose brilliant Greek translation of A.E. Housman’s Fragment of a Greek Tragedy we were delighted to publish some time back.

Raven’s advice draws upon experience of teaching Latin, especially at the University of Oxford, and is informed by the sobering breadth of approaches he would find in examination scripts. So, without further, ado: some advice, given ex negativo, about how we might talk about ancient literature!

How Not to Comment on the Classics

(After the style of various examinees)

sive mutata iuvenem figura

ales in terris imitaris almae

filius Maiae, patiens vocari

Caesaris ultor.

Or, by changing your form, you imitate on earth a young man, son of nourishing Maia, allowing yourself to be called the Caesar’s avenger.

Horace Odes 1.2.41–4

I: The Merely Ignorant

Horace muses on the state of Rome.

II: The Emptily Paraphrasing

Horace suggests that one of the gods, e.g. the son of Maia, may fly down to earth and take the form of a youth, subsequently becoming Caesar’s avenger. This is a Roman ode, such as Horace was fond of writing.

III: The Barely Factual

Horace enumerates a select list of deities who may aid Rome in her long-heralded recovery. In this stanza he invokes Mercury, son of Maia. Maia was a Pleiad. Caesar (l.44) refers to Julius Caesar. Horace wishes the son of Maia to be Caesar’s avenger. Mercury is later to be identified with Augustus. Thus Augustus (= Mercury, = son of Maia) will be Caesar’s avenger. Iuuenem (l.41) – Caesar was young. Mercury was also young when he became the son of Maia. Why he is identified with Augustus is a mystery.

IV: The Gushful

The surge and thunder of Horace’s magnificent verse must not blind us to the fact that he was, when occasion called, capable of a nice shrewdness in his political philosophy. Here the poet has a delicious opportunity of expanding on his favourite theme, the greatness of the young Octavian. He indulges in this predilection with consummate art. Which of the gods – he asks – will aid the mighty giant Rome in her hour of need? It is a particularly happy inspiration that his fancy lights on Mercury, the gracious friend of men and guide of the wandering. Far indeed is this cry from the all-but-despite of the opening of this noble poem, when (in a felicitious tribute to his friend, the immortal Virgil) Horace embroidered on a theme dear to the Georgics – the awe-inspiring portents, the mounting terror of the supernatural, following the murder of the same Caesar whom kindly Maia’s son (disguised, that is, as Octavian) is to avenge. Truly Horace was a great poet.

V: The Irrelevant Essay

The emperor Augustus’ attitude to his court poets provides much field for interest. It is clear that he regarded their propaganda as highly useful to the new order that he was establishing. This fact may be seen in the works of Virgil (echoed in earlier stanzas of this ode) and in many other odes of Horace. The relation of the theme is obvious. This may be an early ode, though certainty is impossible. Certainty often is impossible in dating Horace’s odes, since there is often a lack of references which can be certainly dated. Maia was a Pleiad. Jupiter did not marry her, since he was already married to Juno. This did not deter Maia from having a son. Jupiter had many sons, by no means all of them by Juno.

This skit was first (and last) published by D.S. Raven in the wonderful little book Poetastery and Pastiche (Blackwell, Oxford, 1966) 34–6.

Coda:

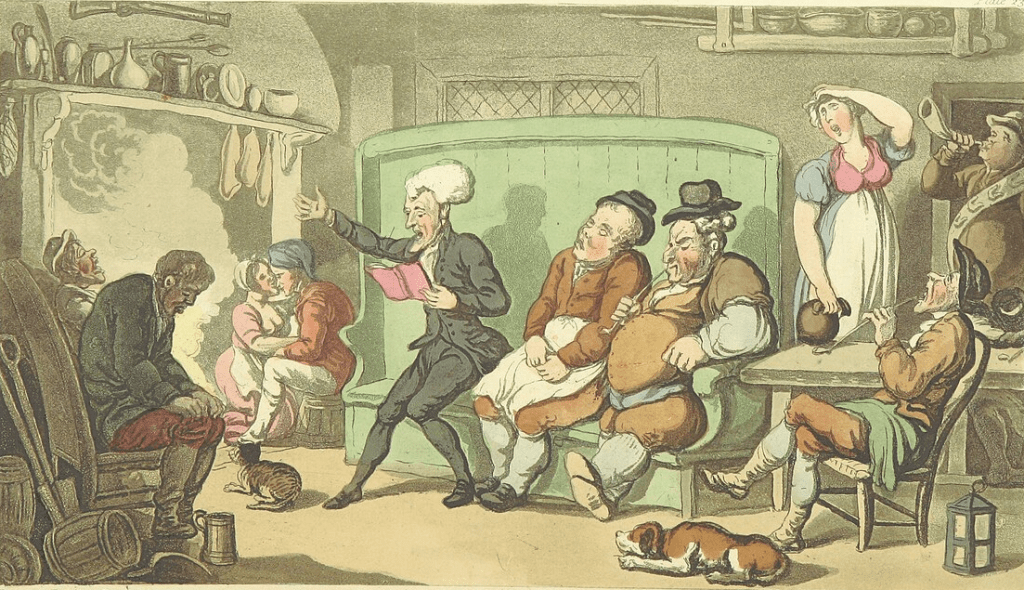

At Antigone we are always forward-thinking, always at the cutting edge of twenty-first-century culture… So, we have applied the Ravenite advice as given above not to ancient lyric but to modern lyrics, in the hope that this affords some instruction and wise counsel to the aspirational contemporary music critic. The text applies to this video, whose viewing figures are edging near what a medium-to-strong Antigone article might garner.

It’s too hard to sleep.

I got the sheets on the floor,

Nothing on me.

And I can’t take it no more:

It’s a hundred degrees.

I got one foot out the door.

Where are my keys?

’cause I gotta leave, yeah.

In the back of the cab

I tipped the driver ahead of time.

“Get me there fast.”

I got your body on my mind –

I want it bad.

Ooh, just the thought of you gets me so high, so high.

Girl, you’re the one I want to want me.

And if you want me, girl, you got me.

There’s nothing I, no, I wouldn’t do, I wouldn’t do

Just to get up next to you.

You open the door

Wearing nothing but a smile, fell to the floor.

And you whisper in my ear, “Baby, I’m yours.”

Ooh, just the thought of you gets me so high, so high.

Jason Joel Desrouleaux, yclept Derulo, Want to Want Me (Warner Bros, 2015)

I: The Merely Ignorant

Mr Derulo seems to have some species of insomnia and/or high fever which affects his subsequent judgment.

II: The Emptily Paraphrasing

Mr Derulo is not sleeping because of a lack of the requisite bedsheets. After a brief logistical hiccup in his door-closure routine, he travels by taxi to meet his “girl”. Having bided the time of travel by singing one of his trademark songs (i.e. this one), the two figures meet: he is welcomed in striking fashion.

III: The Barely Factual

Mr Derulo is having a difficult day: either because of atmospheric conditions (whether he speaks of Fahrenheit or Celsius, it does seem unduly hot) or because of underlying issues with his sleep patterns, on waking he fails to remember the keys by which he can close his own (we must presume) property. His agitated state may explain his use of a private cab and his risky – but nevertheless effective – anticipatory ‘pre-tip’. He seems preternaturally keen to reach the location of the choral addressee, who either is or is at least conceived of as a “girl”. Mr Derulo writes elsewhere in his oeuvre of “girls” and this may form part of a wider song-cycle on the subject. Mr Derulo is prepared to stop at no limit in order to “get up next to” the girl; while the precise spatial configuration envisaged is unclear, there is no doubting the intensity of his desire. When Mr Derulo does meet the girl they exchange pleasantries. Mr Derulo once wrote a song called “Wiggle“.

IV: The Gushful

Like an over-groomed hamster ensconced in a purpose-built mini-sauna, Mr Derulo is feeling the heat: the flames of passion within his breast find sympathetic resonance with the seering warmth of the clime that enshrouds him. Something has to give – and it isn’t going to be this hamster. Casting off the societally-imposed layers – or strata, if you will – of unwa(rra)nted pressure, Mr Derulo breaks free from his hamster-wheel hellscape. He toys briefly with his freshly-achieved transliminal status: half inside and half outside his cicretid past, he offers an aborted aparaclausithyron before demanding, as a newly-fledged Übermensch, an Uber-ordered, over-priced, one-way ticket to the corporeal instantiation of his carnal cravings. Much like the unbridled cataracts of the Upper Zambezi, Mr Derulo’s overpowering oratio (e)recta erupts from the stanza: “Get me there fast” sounds shrill but sensuous – an impatient Siren-call, not just to the now-subjugated driver but to the ever-the-more-impatient reader. Yet (with, oh!, the most wicked and deft suspense) Mr Derulo defers our ‘arrival’ with a choral hymn to the “girl”: not only is the complex and intricate web of (co-)wanter and (co-)wantee established beyond any doubt, but the precarious state of Mr Derulo’s mind is laid bare. His very assertion of the boundlessness of his ambitions to “get up next to” (primus inter parem?) the girl is juxtaposed with homophonous declaration of quasi-Socratic ignorance: “There’s nothing I know (~no).” hinc illae lacrimae – we are told – for utter devotion to the beloved equates with utter oblivion of everything else. Finally, the longed-for uni(f[orn]icati)on occurs; beyond the girl’s artfully minimalist choice of attire, Mr Derulo raises an insoluble puzzle: What “fell to the floor”? Her smile/jaw? She? He? Both parties (so that the ensuing whisper was audible?)? Or, if “fell” derives from Latin fel (“bile”), is this some subconcious bilious eruption of the lyricist who can no longer endure his own hypersaccharine construct? Perhaps we may never know.

V: The Irrelevant Essay

Mr Derulo offers the plaintive lament that he “got the sheets on the floor”. We must ask ourselves how and why this is the case. Six explanations immediately present themselves to the conscientious critic, which it will be essential to survey before we can proceed further:

(i) Mr Derulo has thrown his sheets off his bed purposefully.

(ii) Mr Derulo has sought to abandon one or more of his (several?) sheets in order to alleviate some of his excessive heat, but during this complex manoeuvre he has lost alarmingly more than the single sheet he intended to: he has in fact cast off every single sheet, which was certainly not his original intention.

(iii) Mr Derulo sought temporarily to extract himself from his bed for ‘cool down time’ but the sheets left the bed with him; in his weakened and troubled state he was unable to restore them to their original position, i.e. back on the bed along with him.

(iv) Mr Derulo had no desire to lose his sheets but they fell to the ground either

(a) by gravity or

(b) by foul play wrought

(i) by a human or

(ii) by a hamster.

(v) Mr Derulo is mistaken: the sheets are not on the floor absolutely but are still upon him; since, however, he is indeed lying on the floor, he is correct qua the technicalities of line 2 but signally incorrect qua the claims of line 3.

(vi) Mr Derulo is suffering from one of the many delusions of sleep: he neither has, nor has he ever had, any sheets to speak of, a curious home-furnishings choice that is known and regretted by friends and family alike.

It will be noted that options (ii) and (iii) reflect failings of the body, (v) and (vi) those of the mind – such is the bind of the lover. While option (i) may seem the most natural reading of the passage, I am inclined to take his text as clearly suggesting option (iv)(b)(i); more specifically, it seems likely that this external foul play arose from a maladjusted ‘house-hamster’, whose sheet-based rovings have gradually but inexorably progressed from gentle horseplay to full-scale psychological humiliation.

The hamster may be called “Tiberius Hamsterhuis”. Or he may not be. Those are the two possibilities that stand before us.

Any queries or comments, please do let us know. But otherwise, write bravely and go well, ye criticks-to-be!