Krystyna Bartol

It is never quiet in the mighty jungle of philosophers. Sounds that can be heard there, voiced by real thinkers with well-known names, mingle with the crowd of their unsung supporters, admirers, opponents, and enemies. Their views clash. All tricks are allowed, as long as they discredit those who think differently and gain an audience for certain ideas. This is the law of the jungle.

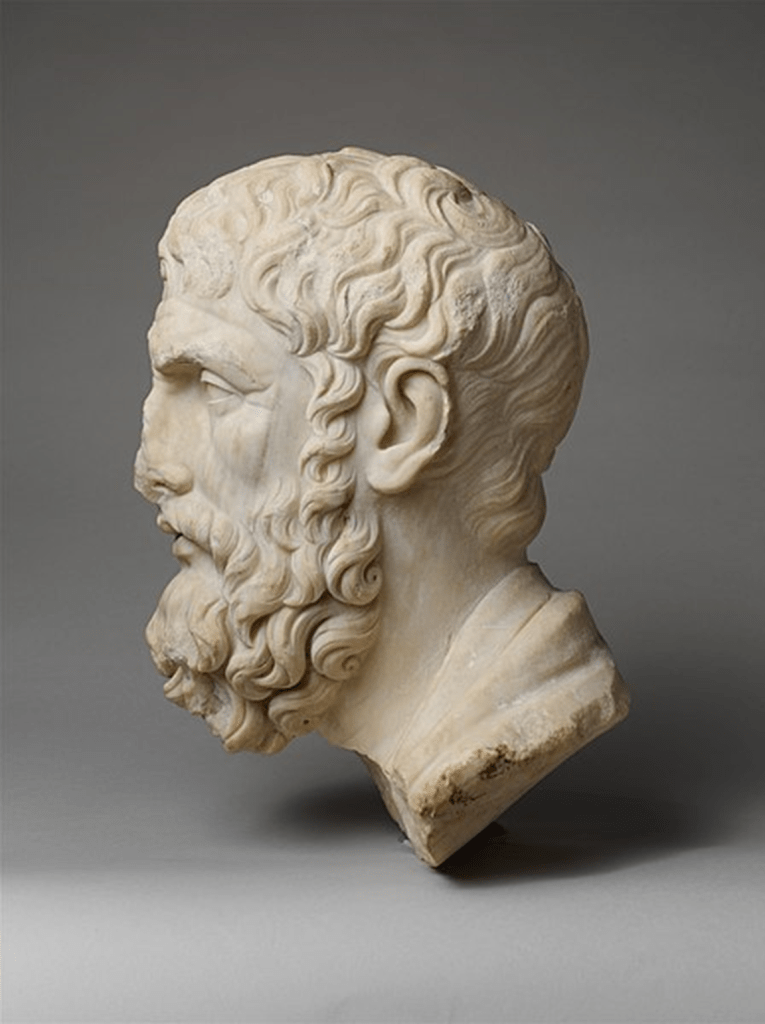

Epicurus, who taught philosophy in Athens in a large backyard garden purchased around 306 BC, like other philosophers at the end of the Classical era and the beginning of Hellenistic times, gave priority to ethical thought in his teaching, treating physics and logic as auxiliary disciplines to facilitate understanding of the human behaviour, attitudes and aspirations he postulated. According to him, the aim of all human actions was to strive for ataraxia (ἀταραξία), that is, a state of inner peace, indifferent to pain and suffering, and to strive for freedom from fear, especially the fear of death and wrath of the gods.

Liberation from fear is possible through the cognition of reality. The tools of this cognition are the senses. They shape human perceptions of the individual elements of the universe, which are formed by combinations of atoms in constant motion. The human soul, in Epicurus’ view, was also material, and its ability to feel ended at the moment of human death, when the delicate atoms that make up the soul separated from the larger atoms of the body. So, as he used to say, Ὁ θάνατος οὐδὲν πρὸς ἡμᾶς, τὸ γὰρ διαλυθὲν ἀναισθητεῖ, τὸ δ᾽ ἀναισθητοῦν οὐδὲν πρὸς ἡμᾶς: “Death is nothing to us; for the body, when it has been resolved into its elements, has no feeling, and that which has no feeling is nothing to us.”[1]

The fear of death is therefore unfounded, as is the fear of disfavour from the gods. For Epicurus, the gods were beings made up of the subtlest atoms, residing somewhere in the inter-worlds, not interfering with the lives of humans, indifferent to their fates and out of touch with them. Man, by his actions, whether good or bad, cannot therefore throw them out of their state of blissful happiness, nor should he fear any reaction to his doings on their part. Epicurus considered pleasure (ἡδονή, hēdonē) to be the highest value, the attainment of which must be subordinated to all actions. He understood it as the absence of pain and suffering, as the absence of anxiety and emotional turmoil, as inner order, harmony and unshakeable peace of mind.

Epicurus became very popular in Athens but, as often happens, over-popularity does not pay. Trying to show people what it means “to live happily”, Epicurus learned quickly what misunderstanding and slander were. This is evidenced by his own words in the Letter to Menoeceus preserved in the tenth book of Diogenes’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers, written in the 3rd century AD. There Epicurus says:

[λέγομεν ἡδονὴν] τὸ μήτε ἀλγεῖν κατὰ σῶμα μήτε ταράττεσθαι κατὰ ψυχήν. οὐ γὰρ πότοι καὶ κῶμοι συνείροντες οὐδ᾽ ἀπολαύσεις παίδων καὶ γυναικῶν οὐδ᾽ ἰχθύων καὶ τῶν ἄλλων, ὅσα φέρει πολυτελὴς τράπεζα, τὸν ἡδὺν γεννᾷ βίον, ἀλλὰ νήφων λογισμὸς καὶ τὰς αἰτίας ἐξερευνῶν πάσης αἱρέσεως καὶ φυγῆς.

By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and the trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking-bouts and of revelry, not sexual love, not the enjoyment of the fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the ground of every choice and avoidance. (ch. 132, tr. R.D. Hicks).

He illustrates his idea of pleasure (hēdonē) with vivid examples:

καὶ τὴν αὐτάρκειαν δὲ ἀγαθὸν μέγα νομίζομεν, οὐχ ἵνα πάντως τοῖς ὀλίγοις χρώμεθα, ἀλλ᾽ ὅπως ἐὰν μὴ ἔχωμεν τὰ πολλά, τοῖς ὀλίγοις ἀρκώμεθα, πεπεισμένοι γνησίως ὅτι ἥδιστα πολυτελείας ἀπολαύουσιν οἱ ἥκιστα ταύτης δεόμενοι, καὶ ὅτι τὸ μὲν φυσικὸν πᾶν εὐπόριστόν ἐστι, τὸ δὲ κενὸν δυσπόριστον. οἱ γὰρ λιτοὶ χυλοὶ ἴσην πολυτελεῖ διαίτῃ τὴν ἡδονὴν ἐπιφέρουσιν, ὅταν ἅπαξ τὸ ἀλγοῦν κατ᾽ ἔνδειαν ἐξαιρεθῇ. καὶ μᾶζα καὶ ὕδωρ τὴν ἀκροτάτην ἀποδίδωσιν ἡδονήν, ἐπειδὰν ἐνδέων τις αὐτὰ προσενέγκηται. τὸ συνεθίζειν οὖν ἐν ταῖς ἁπλαῖς καὶ οὐ πολυτελέσι διαίταις καὶ ὑγιείας ἐστὶ συμπληρωτικὸν καὶ πρὸς τὰς ἀναγκαίας τοῦ βίου χρήσεις ἄοκνον ποιεῖ τὸν ἄνθρωπον καὶ τοῖς πολυτελέσιν ἐκ διαλειμμάτων προσερχομένους κρεῖττον ἡμᾶς διατίθησι καὶ πρὸς τὴν τύχην ἀφόβους παρασκευάζει.

We regard independence of outward thing (autarkeia) as a great good, not so as in all cases to use little, but so as to be contended with little if we have not much, being honestly persuaded that they have the sweetest enjoyment of luxury who stand least in need of it, and that whatever is natural is easily procured and only the vain and worthless hard to win. Plain fare gives as much pleasure as a costly diet, when once the pain of want has been removed, while bread and water confer the highest possible pleasure when they are brought to hungry lips. To habituate one’s self therefore, to simple and inexpensive diet supplies all that is needful for health, and enables a man to meet the necessary requirements of life without shrinking, and it place us in a better condition when we approach at intervals a costly fare and renders us fearless of fortune. (ch. 130–1, tr. R.D. Hicks)

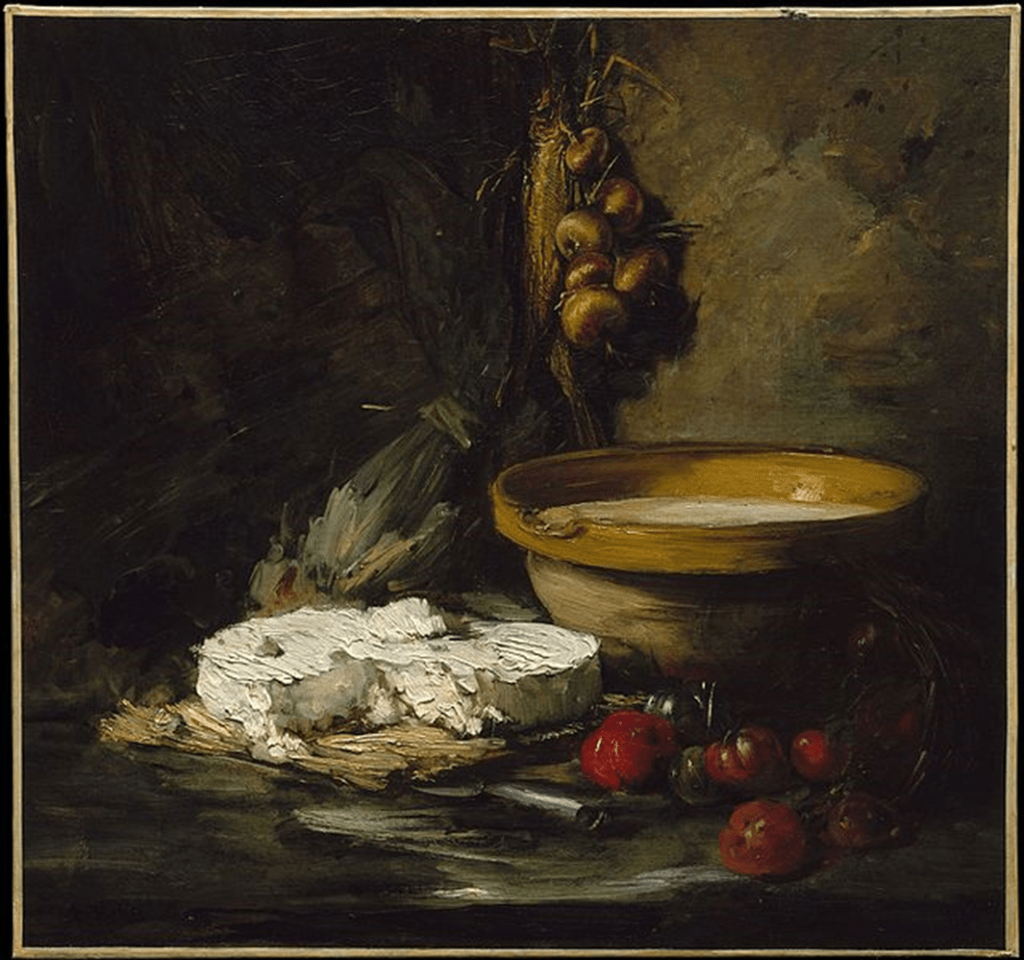

Diocles of Magnesia, the historian of philosophy active around 100 BC, in his Philosophers’ Overview referred to by Diogenes Laertius (10.11) attests that these declarations were reflected in the daily practices of Epicurus and his disciples. He speaks of them “as living a very simple and frugal life”, adding that “at all events they were content with half a pint of thin wine and were, for the rest, thoroughgoing water-drinkers.” Epicurus reportedly instructed one of his friends, “Send me a little pot of cheese so that, when I like, I may fare sumptuously.”

More than two centuries later, this predilection for modest feasting was recalled by the Epicurean Philodemus in an epigram that is a jocular invitation to or a reminder of a ‘potluck’ meal among friends (A.P. 11.35):

Κράμβην Ἀρτεμίδωρος, Ἀρίσταρχος δὲ τάριχον,

βολβίσκους δ᾽ ἡμῖν δῶκεν Ἀθηναγόρας,

ἡπάτιον Φιλόδημος, Ἀπολλοφάνης δὲ δύο μνᾶς

χοιρείου, καὶ τρεῖς ἦσαν ἀπ᾽ ἐχθὲς ἔτι.

ᾠόν, καὶ στεφάνους, καὶ σάμβαλα, καὶ μύρον ἡμῖν

λάμβανε, καὶ δεκάτης εὐθὺ θέλω παράγειν.

Artemidorus gave us a cabbage, Aristarchus caviare, Athenagoras little onions, Philodemus a small liver, and Apollophanes two pounds of pork, and there were three pounds still over from yesterday. Go and buy us an egg and garlands and sandals and scent, and I wish them to be here at four o’clock sharp. (tr. W.R. Paton)

Mocking statements against Epicurus and his circle of disciples originated from misrepresentations and taunting references to selected points of his teaching. These appear almost from the time that the ‘Master of the Garden’ was running his school. They form part of the general anti-philosophical current that was popular in contemporary Greek comedy. Mockery of philosophers who were professionally soulful, insensitive to the temptations of this world, and suspected to love luxury and indulge in sensual pleasures privately, was present in Attic comedy from the beginning of its history.

It does not appear that Epicurus’ doctrine exposing pleasure as the basis of a happy life was particularly targeted by comic playwrights. After all, they also bluntly ridiculed Plato and the Cynics, mocking issues discussed in the Academy, the verbal jargon of Platonists and their predilection for luxurious clothes,[2] or teasing about the Cynics’ excessive appetite.[3] Middle and New Comedy was obsessed with culinary themes, featuring as they did cooks, gluttons, parasites, and philosophers; they gleefully turned upside down that key word of Epicurus’ philosophy – pleasure (hēdonē) – and gave it the ordinary or vulgarised meaning of a lack of moderation, or even sensual excessiveness.

In the mid-3rd century BC, the comic playwright Baton, in a play entitled Partner in Deception (Συνεξαπατῶν), depicts a conversation between a father and his son’s guardian:

Α. ἀπολώλεκας τὸ μειράκιόν μου παραλαβών,

ἀκάθαρτε, καὶ πέπεικας ἐλθεῖν ἐς βίον

ἀλλότριον αὑτοῦ, καὶ πότους ἑωθινοὺς

πίνει διὰ σὲ νῦν, πρότερον οὐκ εἰθισμένος.

Β. εἶτ᾽ εἰ μεμάθηκε, δέσποτα, ζῆν, ἐγκαλεῖς;

Α. ζῆν δ᾽ ἐστὶ τὸ τοιοῦθ᾽; Β. ὡς λέγουσιν οἱ σοφοί:

ὁ γοῦν Ἐπίκουρός φησιν εἶναι τἀγαθὸν

τὴν ἡδονὴν δήπουθεν. οὐκ ἔστιν δ᾽ ἔχειν

ταύτην ἑτέρωθεν

(Father) You’ve taken my boy and ruined him,

you bastard! And you’ve convinced him to adopt a lifestyle

that’s foreign to him! He’s drinking in the morning

now, because of you – which isn’t something he used to do.

(Guardian) Are you complaining, master, because he’s learned how to live?

(Father) Is this sort of behaviour ‘living”?

(Guardian) That’s what the wise say. Epicurus, for example, identified the Good with pleasure, I believe. And you can’t get pleasure from anywhere else. (Fr. 5 K.-A., tr. S.D. Olson)

A sensual pleasure, erotic and culinary, as recommended by Epicurus, also appears in a play by the same author entitled The Murderer (Ἀνδροφόνος). The speaker says:

ἐξὸν γυναῖκ᾽ ἔχοντα κατακεῖσθαι καλὴν

καὶ Λεσβίου χυτρῖδε λαμβάνειν δύο.

ὁ φρόνιμος <οὗτός> ἐστι, τοῦτο τἀγαθόν.

Ἐπίκουρος ἔλεγε ταῦθ᾽ ἃ νῦν ἐγὼ λέγω.

When a man can lie down with a beautiful woman in his arms,

and have two little pots of Lesbian wine –

this is “the thoughtful man”, this is ”the Good”!

Epicurus used to say exactly what I’m saying now. (Fr. 3, tr. S.D. Olson)

Hagesippus, the author of the comedy entitled Men who were Fond of their Comrades (Φιλέταιροι) presents a character who, on the authority of Epicurus, reduces pleasure to the act of chewing:

Ἐπίκουρος ὁ σοφὸς ἀξιώσαντός τινος

εἰπεῖν πρὸς αὐτὸν ὅτι ποτ᾽ ἐστὶ τἀγαθόν,

ὃ διὰ τέλους ζητοῦσιν, εἶπεν ἡδονήν.

Β. εὖ γ᾽, ὦ κράτιστ᾽ ἄνθρωπε καὶ σοφώτατε.

τοῦ γὰρ μασᾶσθαι κρεῖττον οὐκ ἔστ᾽ οὐδὲ ἓν

ἀγαθόν. Α. πρόσεστιν ἡδονῇ γὰρ τἀγαθόν.

When someone demanded that the wise Epicurus

tell him what “the Good” they’re

constantly looking for is, he said it was pleasure.

Well done, best and wisest!

There’s no greater good than chewing;

The Good’s an attribute of pleasure. (Fr. 2 K.-A., tr. S.D. Olson).

A more sophisticated wit is afforded by the poet Damoxenus, in whose play Foster-brothers (Σύντροφοι) the cook bravely presents himself as an Epicurean and proves that the masterful art of cooking puts into practice the supreme good of pleasure. He says:

Ἐπικούρου δέ με

ὁρᾷς μαθητὴν ὄντα τοῦ σοφοῦ, παρ᾽ ᾧ

ἐν δύ᾽ ἔτεσιν καὶ μησὶν οὐχ ὅλοις δέκα

τάλαντ᾽ ἐγώ σοι κατεπύκνωσα τέτταρα.

You see that I’m

a student of the wise Epicurus, in whose house

in less than two years and the months

… I ‘condensed’ four talents. (fr. 2.1-4 K.-A., tr. S.D. Olson)

and adds…

Ἐπίκουρος οὕτω κατεπύκνου τὴν ἡδονήν.

ἐμασᾶτ᾽ ἐπιμελῶς. οἶδε τἀγαθὸν μόνος

ἐκεῖνος οἷόν ἐστιν.

This is how Epicurus ‘condensed’ pleasure:

he chewed carefully. He’s the only person

who knew what the Good is. (Fr. 2, 61-3 K.-A., tr. S.D. Olson)

He uses the verb καταπυκνόω (katapyknoō, “to condense”) to refer parodically to Epicurean vocabulary. While Epicurus, speaking of the “condensation of pleasure” meant a complete painless state of body and mind, the Damoxenian cook implies it consists in getting the highest possible amount of sensual delight or material profit.

It seems that the aim of the comedy was to create a sharp contrast between the purely philosophical interpretation of Epicurean pleasure marked by the idea of cheerful moderation and its pastiche evocation on the stage, a contrast recognisable to the theatre audience. The comic falsification of the essence of Epicurean doctrine does not, however, have the flavour of fierce polemical misrepresentation, but is rather a spontaneous, playful reaction to the expressive concept of happiness proposed by Epicurus, which must have fascinated and yet intrigued the people of Athens.

Far more malicious and hostile to Epicurus than the comedy pranksters must have been the liars who spread slanders about his behaviour in order to discredit his philosophy. Diogenes Laertius (10.3–8) mentions the lies of these “stark mad people”. They allege that he was bawdy and insolent, that:

he used to go round with his mother to cottages and read charms… that he put forward as his own the doctrine of Democritus about atoms and of Aristippus about pleasure, that he was not a genuine Athenian citizen… that he vomited twice a day from over-indulgence… that he spent a whole mina daily on his table… that among courtesans who consorted with him were Mammarion and Hedia and Erotion and Nikidion and that he notoriously insulted others.

In all of these slanderous pseudo-biographical references, there is an echo of the distorted understanding of Epicurean pleasure, whereby it meant indulging in sensual delights. This is precisely what the post-Classical expert on Classical Greek culture, Athenaeus of Naucratis, the author of the Deipnosophistae, or The Learned Banqueters, a huge prose work around AD 200, alludes to. In this gargantuan work about food and eaters[4] he replicates the image of Epicurus and his carefree merrymaking devotees which emerged from the works of the fantasists of previous generations. He joins the ranks of those who trump up false stories about Epicurus to enhance their argument about luxury with spectacular examples.

Athenaeus is fond of criticising the feasts of Epicurean friends, which he describes as “made up of a crowd of flatterers who praise one another” (5.182a). This is an obvious distortion of the idea of friendshsip, which according to Epicurus is an immortal good available to noble man. Athenaeus trivialises Epicurus’ thoughts about pleasure as the supreme good. He shallows his thought and treats it superficially, citing Epicurus’ alleged words repeated by his opponents: ἀρχὴ καὶ ῥίζα παντὸς ἀγαθοῦ ἡ τῆς γαστρὸς ἡδονή, καὶ τὰ σοφὰ καὶ τὰ περιττὰ εἰς ταύτην ἔχει τὴν ἀναφοράν (“The pleasure derived from the belly is the origin and root of every good, and whatever is wise or exceptional is so by reference to it,” 7.280a, tr. Olson)). He also accuses Epicurus of a lack of originality, and cites excerpts from Homer’s Odyssey[5]. and Sophocles’ Antigone[6] to confirm that he was not the first to recognise the pleasure of feasting. The portrayal of Epicurus as a kind of sybarite serves Athenaeus, an incredibly well-read man, to show off his own erudition and knowledge of the works of ancient authors. He does not care much about the credibility of repeated information and thus contributes to the dissemination of a deceitful image of the philosopher.

It is said that a lie has speed but the truth has endurance. Perhaps it does. Yet when we look at Plutarch’s treatment of Epicurus, we see that endurance in lying also happens. This philosopher, who lived between around 46 and 119 AD, was an expert in the philosophical thought of all Greek schools, while essentially being a Platonist. He emerged to be a great moral authority for the ancients as well as for modern people from the Renaissance onwards, and dedicated several writings to describing and dissecting Epicurus’ doctrines.

Plutarch’s methodological duplicity and – let us call a spade a spade – cynicism (equalled perhaps only by some present-day politicians) are striking. At the beginning of the work whose Latin title[7] is Non posse suaviter vivi secundum Epicurum (That it is not Possible to Live Pleasurably According to the Doctrine of Epicurus), he postulates honesty in the presentation of others’ views (1086D). He says: “they [i.e. those who contradict other men] ought not to run cursorily over the discourses and writings of those they would disprove, nor by tearing out one word here and another there.”

On the other hand, Plutarch himself violates this rule and shows how one can manipulate the statements of others. In particular, he presents the Epicurean concept of pleasure very selectively, limiting it to bodily conditions while reducing spiritual pleasures solely to the memory of bodily conditions or the anticipation of them. Plutarch mocks Epicurus’ famous precept Live unnoticed (Lathe biōsās) interpreting it as a call for not caring about the common good and state affairs, but as the praise of selfishness and not thinking of others. In fact, Epicurus was recommending the enjoyment small, everyday things and advising against the pursuit of glory and wealth. Plutarch also makes an unfair accusation against Epicurus by alleging his disbelief in the gods. In most cases, he does this by deploying words and sentences taken out of context from Epicurus’ writings. Plutarch thus paints a virulent picture of the Epicureans who claim not to care about the welfare of Greeks, but to eat and drink, not in a manner that avoids harming the stomach, but in a manner that seeks to please it. He concludes (1107C):

Ἐπίκουρος ἐκτέμνεται καὶ ἐπὶ ταῖς ἐκ θεῶν ἐλπίσιν ὥσπερ εἴρηται καὶ χάρισιν ἀναιρεθείσαις τοῦ θεωρητικοῦ τὸ φιλομαθὲς καὶ τοῦ πρακτικοῦ τὸ φιλότιμον ἀποτυφλώσας εἰς στενόν τι κομιδῇ καὶ οὐδὲ καθαρὸν τὸ ἐπὶ τῇ σαρκὶ τῆς ψυχῆς χαῖρον συνέστειλε καὶ κατέβαλε τὴν φύσιν, ὡς μεῖζον ἀγαθὸν τοῦ τὸ κακὸν φεύγειν οὐδὲν ἔχουσαν.

Epicurus… destroys the hopes and graces we should derive from the Gods, and by that extinguishes both in our speculative capacity the desire of knowledge, and in our active capacity the love of glory, and confines and abases our nature to a poor narrow thing and that not cleanly neither, to wit, the content the mind received by the body, as if it were capable of no higher good than the escape of evil. (tr. W. Baxter)

Thus, Plutarch sees only absurdities in Epicurus’ selectively and ironically presented doctrine. That said, earlier serious ancient authorities, such as Cicero (De finibus bonorum et malorum, On the ends of good and evil, 1.28.90) and Seneca (De constantia sapientis, On the Firmness of the Wise Person, 15.4), spoke positively of the therapeutic message of Epicurus’ ethical teachings, and warned against doing what Plutarch did, namely distorting its essence.

What was the reaction of the vilified Epicureans themselves? They seem to have realised early on that the label of trough-seeking hogs pinned to them by their enemies does more to expose their opponents’ ignorance and coarse viciousness than it does to disgrace themselves. This attitude is evidenced by Horace, who in the letter of invitation addressed to Tibullus (Epist. 1.4), an elegiac love poet, humorously marks his interim affinities for the Epicureans, calling himself “a sleek and flat, well-cared-for hog, one of Epicurus’ herd” (me pinguem et nitidum bene curata cute vides,… Epicuri de grege porcum).

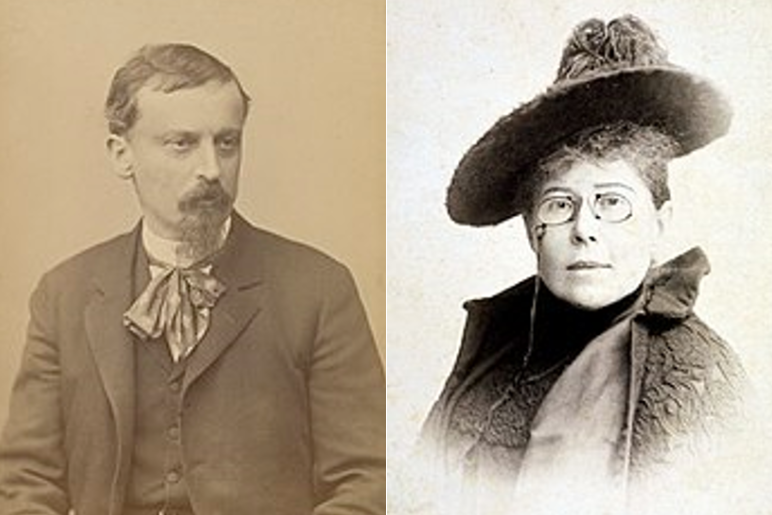

Big liars of antiquity inspire modern writers. The stereotype of the dissolute Epicurean appears frequently in literary fiction, sometimes with, and sometimes without, the indication that this is a false image of the doctrine of Epicurus. Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846–1916), the Polish writer, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature for his novel Quo Vadis, wrote a short story entitled Let us follow him (Pójdźmy za Nim). Set in Nero’s Rome, it describes the luxurious lifestyle of a certain Gaius Septimius Cinna, the Roman bon vivant: “He did not know the true doctrine of Epicurus, as a result of which he considered himself an Epicurean.” Another Polish writer of the same period, the popular novelist Maria Konopnicka (1842–1910) –who among Polish schoolchildren does not know her Little Orphan Mary and the Gnomes? – was a highly patriotic social activist.

In her short story entitled The Year 1835 (Z 1835 roku) she portrays with bitter irony a Polish convict, an insurgent of the uprising, sent to Nerchinsk katorga (penal labour) in the Russian Far East (Zabaykalsky Krai). He constantly declares his permanent adoration of Epicurus, both for his promotion of pleasure and his praise of civilisation. When seeing a fellow drunkard breaking emptied bottles, he says: “Great, bravo! at least our successors will not say that there was no civilisation in Nerchinsk. When others will find these bottles, they will be glad to say, ‘Here are the traces of thoughts of our compatriots’.”

The big liars are still not asleep. If you take the time to consult a dictionary (Collins, Merriam-Webster, OED, or whatever) and flick to the entry “Epicurean”, you will find a list of synonyms such as “luxurious, sensual, lush, luscious, voluptuous, pleasure-seeking, gluttonous, gourmandising.” You will immediately recognise how perennial this fraudulent misinterpretation of Epicurus’ philosophy is. The rumble in the jungle can still be heard…

Krystyna Bartol is a professor at the Institute of Classical Philology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland. She writes on Greek poetry, especially lyric, and Greek Imperial prose. She translated into Polish the works of Epicurus’ followers (Philodemus’ Epigrams, On Music, On Poems) as well as those of his deceitful opponents: selected fragments of Greek comic poets, Athenaeus’ Deipnosophists (in cooperation with Jerzy Danielewicz), and the dialogue On Music ascribed to Plutarch. She has previously written for Antigone on Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae, Oppian’s Halieutica, Greek music and Greek elegy. She shares Epicurus’ tyrophilic attitude.

Further Reading

Those interested in the teachings of Epicurus should consult The Oxford Handbook to Epicurus and Epicureanism, edited by Philip Mitsis (Oxford UP, 2020) which offers authoritative discussions of all aspects of his philosophy and its reception in antiquity as well as throughout the Western intellectual tradition. As for the big liars, the image of Epicurus and his followers in Greek comedy is presented in an absolutely fascinating way by Pamela Gordon in one of the chapters of her book The Invention and Gendering of Epicurus (Univ. of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2012, 14–37).

In turn, there is much to learn from Richard Stoneman’s chapter “You are what you eat: diet and philosophical diaita in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae,” in D. Braund & J. Wilkins (edd.), Athenaeus and His World: Reading Greek Culture in the Roman Empire (Univ. of Exeter Press, 2000) 413–22: he surveys Athenaeus’ discussion of Epicurus and the Epicureans, with that philosopher emerging, as Stoneman says, “as the villain of the piece, the opposite of everything that a philosopher ought to be.” Plutarch, the anti-Epicurean, is skillfully presented by Michael Erler in Chapter 20 (Plutarch) of the aforementioned Oxford Handbook to Epicurus and Epicureanism (507–30).

Notes

| ⇧1 | These words were recorded in Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Philosphers 10.139, as translated by R.D. Hicks. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | For example, the comic poet Epicrates (fr. 10 K.-A.) introduced a character on the stage who when asked “What about Plato and Speusippus and Menedemus? What’s occupying their time nowadays?” talks about a discussion he had at the Academy to determine which category the gourd belongs to, and bluntly describes the reaction of a Sicilian doctor who, “when he heard this, farted on them for talking nonsense” (tr. S.D. Olson). The comic poet Antiphanes mocks Platonists’ luxurious lifestyle in a play entitled Antaeus (fr 35 K.-A.): “Who do you think this old man is? He’s Greek, by the looks of him: a white mantle, a nice little gray cloak; a small, soft felt cap, an elegant staff… Why should I go on at length? I think I’m seeing the Academy itself, pure and simple.”(tr. S.D. Olson). |

| ⇧3 | As the comic poet Eubulus does (fr. 137 K.-A.) calling them “unholy gullers, who dine on other people’s goods… snatchers of casserole dishes full of whote belly-steaks.” (tr. S.D. Olson). |

| ⇧4 | I have written much more about it here. |

| ⇧5 | At 12.513b, he cites Od. 9.5-11: οὐ γὰρ ἔγωγέ τι φημὶ τέλος χαριέστερον εἶναι | ἢ ὅταν εὐφροσύνη μὲν ἔχῃ κατὰ δῆμον ἅπαντα, | δαιτυμόνες δ᾽ ἀνὰ δώματ᾽ ἀκουάζωνται ἀοιδοῦ | ἥμενοι ἑξείης, παρὰ δὲ πλήθωσι τράπεζαι | σίτου καὶ κρειῶν, μέθυ δ᾽ ἐκ κρητῆρος ἀφύσσων | οἰνοχόος παρέχῃσι καὶ ἐγχείῃ δεπάεσσιν. | τοῦτό τί μοι κάλλιστον ἐνὶ φρεσὶν εἴδεται εἶναι. (For I declare that there is no greater height of happiness than when joy prevails and wickedness is absent, and feasters are in the house listening to a bard, seated in a row, and the tables beside them are full of bread and meat, and the wine-steward draws wine from a mixing-bowl and offers it to them, pouring it into their goblets. This seems to me in my mind to be what is best; tr. S.D. Olson). |

| ⇧6 | At 7.280b-c and 12.547c, he cites Ant. 1165–71: τὰς γὰρ ἡδονὰς | ὅταν προδῶσιν ἄνδρες, οὐ τίθημ᾽ ἐγὼ | ζῆν τοῦτον, ἀλλ᾽ ἔμψυχον ἡγοῦμαι νεκρόν. | πλούτει τε γὰρ κατ᾽ οἶκον, εἰ βούλει, μέγα | καὶ ζῆ τύραννον σχῆμ᾽ ἔχων: ἐὰν δ᾽ ἀπῇ | τούτων τὸ χαίρειν, τἄλλ᾽ ἐγὼ καπνοῦ σκιᾶς | οὐκ ἂν πριαίμην ἀνδρὶ πρὸς τὴν ἡδονήν. (Because in fact, when a man can no longer enjoy himself, I don’t regard him as alive; I consider him a living corpse. Have enormous wealth in your house, if you like, and spend your time dressed like a king! If no joy goes along with that, I wouldn’t buy the rest of it from someone for a plugged nickel, compared to pleasure; tr. S.D. Olson). |

| ⇧7 | The original Greek title is Ὅτι οὐδὲ ἡδέως ζῆν ἔστι κατ’ Ἐπίκουρον, but by convention Plutarch’s treatises are referred to by their Latin names. |