A.M. Juster

I have loved poetry since I was young. When I was about three, my mother would take me to the front yard under our big tree and read poems to me, mostly Dr. Seuss and A.A. Milne. When I was eight, I won a school Arbor Day poetry contest and my entry appeared in our small-town newspaper. My teacher buried that poem in a time capsule in the roots of a newly-planted tree beside the school parking lot, and I still have nightmares that it will be discovered someday.

I have also loved politics for most of my life. One of my first memories is John F. Kennedy being elected President in 1960. I had posters of rocket ships on my walls and dreamed of beating John Glenn into space. Kennedy gave Catholics great pride. Boston was not far from its “Irish need not apply” want ads, and my Boston Irish mother, who had a strong academic record at Boston Latin, was not able to go to college. You can probably sense my feelings in this elegy I wrote about the death of John F. Kennedy Jr.

When I was eleven, my parents sent me to Roxbury Latin School, which required five years of Latin. My seventh-grade Latin teacher Dennis Kratz (later a revered professor and administrator at the University of Texas at Dallas) was fun and youthful, and slightly subversive. Almost a century earlier, the school had originated Exelauno Day, at which all students in first-year Latin were required to compete in the annual declamation contest.

Instead of the usual dreary segments of Cicero or the histories (Martial, Catullus and Ovid being too raunchy for children of our age…), he assigned us a medieval drinking song, which led to the first of my subversive stunts. I realized that “Iam lucis orto sidere” could be sung to the tune of “A Hundred Bottles of Beer on the Wall”, so I organized a small group of friends to sing it in the hallway near where the administrators worked. The performance paralyzed them: they could not decide whether to punish us for raucous behavior or to commend us for rare enthusiasm for the language.

In hindsight, I learned two important lessons: Latin literature did not end with Seneca and Juvenal in the early 2nd century AD, and the Classics could be fun. The next two years did their best to extract those lessons from my soul, but in my sophomore year Dennis Kratz returned with his new PhD from Harvard and assigned a medieval epic, Waltharius. Since it was still ‘the Sixties’, even though it was 1972, we had to do an independent project. Given that I had no talent for art, I translated the poem into English iambic pentameter, my first attempt at literary translation.

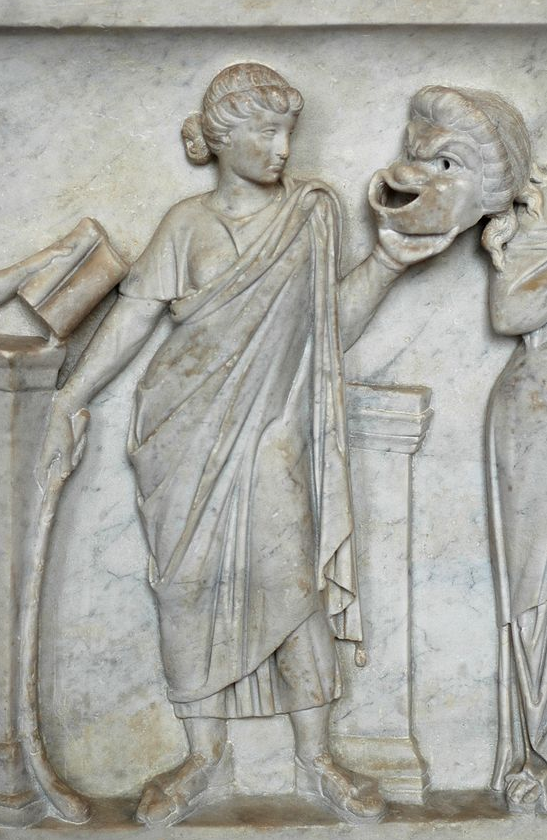

In 1974, after playing a bit role in a Roxbury Latin production of Aristophanes’ The Clouds, I headed to Yale with the intention of becoming an English teacher, then upgraded that dream to becoming an English professor. My classmate fianceé (now wife) and I both wrote our senior essays on Chaucer, although I didn’t understand her linguistic analysis and she didn’t understand my Boethian analysis (there is a joke in there somewhere…).

I was active in the Yale Political Union, and in 1976 pulled off an upset. The parties of the left had swept twenty consecutive Union elections, but I was elected president with the endorsement of the two parties on the right, the centrist party, and a rare no-endorsement vote of the Liberal Party. The following year that election changed my life. I came close to winning Marshall and Rhodes Scholarships, but then was called into the Career Advisory Office by the director, Priscilla Elfrey. She told me that a university committee had selected me for a prestigious fellowship, but she had nixed it because “people with your politics shouldn’t be in academia”. It didn’t matter that at that time most Massachusetts Republicans were indistinguishable ideologically from the Democrats – and less given to corruption.

I was not offered enough financial aid for graduate school, so my future bride and I headed off to work for Members of Congress, which started a career far more satisfying than the one I had planned. After about ten years, though, with my wife’s encouragement, I came back to poetry on the side, though I decided I wanted to write verse closer to what my mother had taught me than what Harold Bloom had.

In order to write formal poetry, I spent a lot of time translating it as an exercise, first in French because it was my strongest language at that time, and then in Latin because with a congested work and family schedule I could get satisfaction from knocking off an epigram before bed or in a stray hour of a weekend afternoon. Eventually, I got hooked on translation for its own sake. I realized that a host of translators focused on about a dozen European poets, but that otherwise the field was wide open for a dangerous amateur.

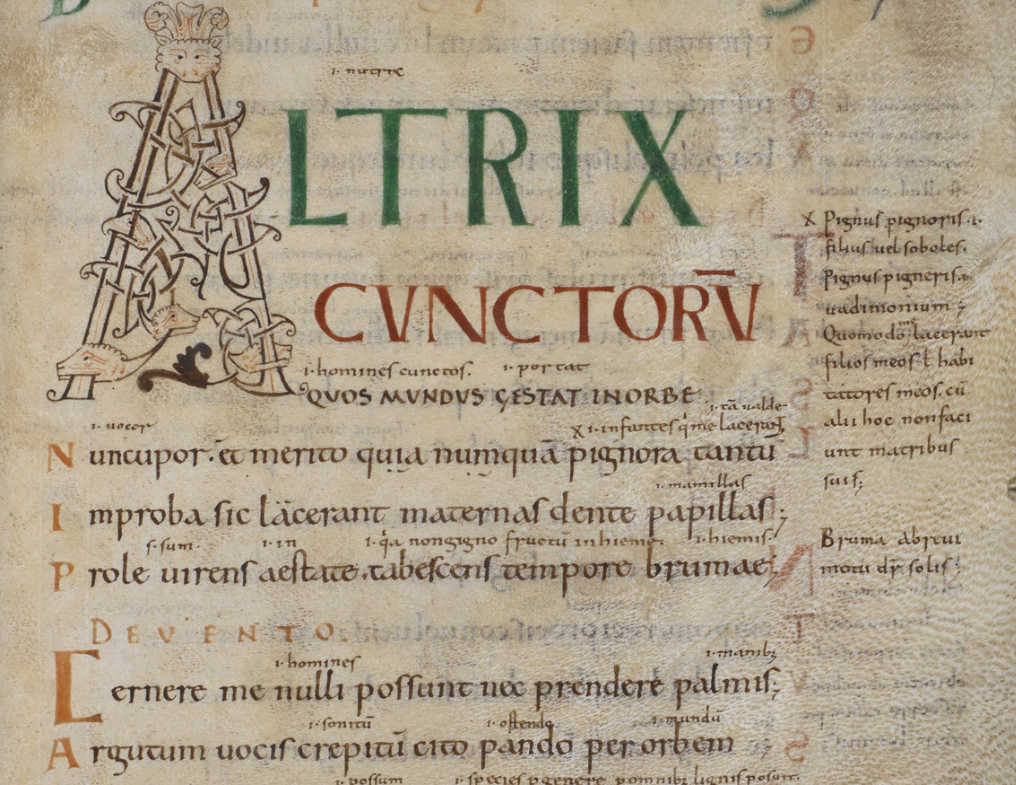

My Roxbury Latin days still influenced my tastes – I did not like war poetry and I was increasingly indignant about the contempt of most Classicists for Late Antique and medieval literature. I enjoyed translating overlooked texts such as the 7th-century riddles of Saint Aldhelm and the 6th-century elegies of Maximianus, and even became so absorbed by those two works that I wrote commentaries on them. I loved other obscure Late Antique poems, such as Eucheria’s Adynata, which I believe is the oldest funny poem in Latin by a woman; Lactantius’ Christianization of Ovid’s phoenix myth; and the one funny epigram by the repulsive North African poet Luxorius.

While working on Aldhelm’s riddles, I learned about his extensive library, and in particular a document indicating that Aldhelm owned a copy of Lucan’s Orpheus. Lucan was a brilliant and prolific poet who was forced to commit suicide at the age of 25 because he joined a conspiracy against the erratic and tyrannical Emperor Nero (r. AD 54–68). Lucan’s De Bello Civili (On the Civil War) survived, and the Laus Pisonis (Praise of Piso) may also be his work, but there are about a dozen other works of his that were destroyed in the damnatio memoriae after his death. Aldhelm’s lost copy of Lucan’s Orpheus has always made me profoundly sad.

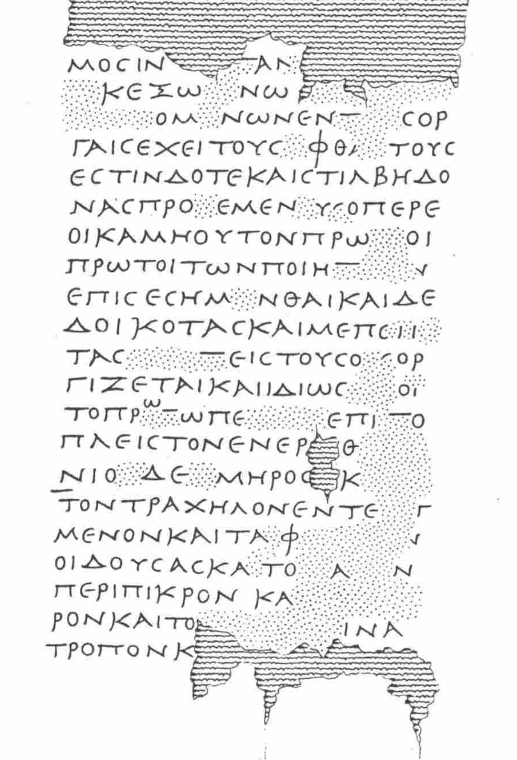

That sadness returned after we visited Herculaneum, the Roman town destoyed by the volcanic eruption of Mt Vesuvius in AD 79. I started thinking about the densely carbonized papyrus scrolls of one large library there (perhaps owned by one of Julius Caesar’s in-laws). I had once briefly served as acting CEO of a company that developed innovative pharmaceuticals for magnetic resonance imaging, so soon I became excited by efforts to use imaging technology to read the scrolls electronically. Academic infighting slowed those efforts for years, but the project gained momentum, and now artificial intelligence should help with the laborious task ahead.

The few scrolls that could be physically unrolled and deciphered contain texts of Greek philosophy. Some academics have asserted – somewhat facilely in my opinion – that the library is a specialized one and contains only philosophy texts. I reject that opinion; many of us own specialized libraries, as I do, but I have never heard of anyone who owned about 1,100 texts exclusively on one subject, so I hold out hope that lost works of Aristophanes, Euripides, and other great writers may be waiting for us in those scrolls.

My sentimental feelings about lost texts kicked in again five years ago when I bought two Loeb books, Aristophanes’ Fragments,edited by Jeffrey Henderson, and Euripides’ Fragments, edited by Christopher Collard and Martin Cropp. After I sent a huge project off to one of my publishers, I was looking to write something fun. I had started working on a children’s poem for our bookish granddaughters, but still wanted another project. The Euripides fragments were too grim for my mood, but I found myself enjoying visions of lost Aristophanes comedies. Something clicked when I read this Henderson translation of a description of Gerytades from Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae (12 551):

And Aristophanes selects slender men, the tragic poets Sannyrion, and Meletus and Cinesias, whom he says were sent by the poets down there, and he calls them Hades-Haunters, whom he says were also riding on slender hopes.

The phrase “slender men” puzzled me at first, but as soon as I substituted “lightweight” for “slender,” it worked for me. These were stock characters designed to set up jokes, not personalities who would grow and teach. Shortly thereafter Athenaeus makes their stock nature clear and identifies Meletus as the tragedian, Sannyrion as the comic poet, and Cinesias as the writer of drinking songs.

So far so good. Athenaeus mentions the poets being chosen together, “meeting as an assembly”. Well, what happens when a lot of poets gather? They eat too much, drink too much, and display pettiness; AWP afterparties (for the Association of Writers and Writing Programs) are not much different, I suspect, than such gatherings in Ancient Athens. Again, it all seemed plausible.

I then puzzled over the purpose of the meeting. Why would poets be told literally to go to Hell? It seemed to me that here the plot was paralleling Aristophanes’ own comedy The Frogs, where Dionysus was sent to retrieve Euripides from Hades. Since the goal in Gerytades appeared to be saving poetry, the same Orpheus who inspired Lucan was my nominee to be the rescuer in Gerytades, although Professor Henderson suggests the goddess Poetry.

At about this point, I had to figure out who Gerytades was because the fragments gave no real clue. It seemed to me that there were plenty of well-known figures in the Underworld, and there was no likelihood that the character for whom the play is named would be a previously unknown person popping up in the second half of the play. The more I thought about it, the more I became persuaded (undoubtedly self-delusionally) that he had to be the instigator of the mission to the Underworld, so I made him the orchestrator of the poets’ party and included him in the journey to Hades – to lose him before that seemed inconsistent with his apparent significance in the play. Also, Professor Henderson points out that the name “Gerytades” is a comic patronymic – meaning something like “son of voice” or “sound” – which tends to suggest that he was a literary figure.

After some indecision I decided that the play probably had a chorus, and that the way to add comic tension was to make it a group of fussy literary critics. Although I used heroic couplets for the body of the story because that is still what we expect from comic poetry, for the chorus I used alternating rhymed iambic tetrameter and trimeter because that rhythm gave the lines more intensity. In the second draft, I added a prologue by Euripides, which gave me a chance to lay out the limitations of my tale and be appropriately self-deprecatory.

I researched the length and terrain of the tough journey from Athens to the portal to Hell in the mountains of Cape Matapan in the southernmost part of Greece. The four protagonists didn’t strike me as hardy outdoors types, so I gave them an inn about halfway, as well as an inn on Cape Matapan.

The two inns were as far as I could go without figuring out most of the rest of my plot. There is a reference in the fragments to the filth of the Styx, so crossing that river seemed obligatory. It also seemed to me that our would-be saviors were so unsuited to their task that they would never get across the Styx, a thought which also had the advantage of simplifying a story that risked getting out of hand. There is a lot of activity on the far side of the Styx and relatively little on the near side. Traditional inhabitants of the near side, such as Cerberus the three-headed dog (one head for each poet, I decided), make appearances in my Gerytades that Aristophanes’ audience probably would have expected.

Once I made these choices, I had to decide why the poets failed to cross the Styx, and concluded that the most likely reason was that they had no money. It also seemed unlikely, though, that they would forget about their need to pay the ferryman. Accordingly, I fell back on the stock trope of a roll in the hay with unscrupulous young women. There is some support for that theory in the fragments: one mentions a courtesan named Lysias and another uses terms for what Professor Henderson calls “women in heat”.

Without any specific textual support, I had the three poets converse with Orpheus across the Styx; his words are still magical and he is still smitten by Eurydice. That scene was great fun, but it also saddened me to be reminded of tyrants, natural disasters, and other calamities that can at a stroke deprive us of great literature.

A.M. Juster’s Gerytades: An Aristophanes Play…sort of is available from the Classics publisher Contubernales Books here. He served in senior roles for four presidents, including six years as Commissioner of Social Security. His real Classical translations include Horace’s Satires (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), Tibullus’ Elegies (Oxford UP, 2011); Aldhelm’s Riddles (Univ. of Toronto Press, 2016), The Elegies of Maximianus (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), and John Milton’s Elegies (Paideia Institute Press, 2019). He tweets too much about formal poetry and translation at @amjuster.