Robin Alington Maguire

There are many ancient accounts of springs of fresh water issuing forth from the bed of the sea. At first encounter, such stories may sound more like myth than history. However, several undersea springs are well attested by Classical writers and some are still flowing today.

Caesar and Napoleon in Epirus

Early in 48 BC Caesar crossed the Adriatic from Brundisium in Italy to Epirus in northwest Greece in pursuit of Pompey the Great and the senatorial army, The expedition culminated in Caesar’s victory over Pompey at Pharsalus seven months later.

Caesar’s own account of the Civil War (BC 3.6) describes his landfall in Epirus:

Having found a quiet harbourage among the Ceraunian rocks and other dangerous places, and fearing all the ports, which he believed to be in the occupation of the enemy, he disembarked his troops at a place called Palaeste without damage to a single one of his ships. (tr. A.G. Peskett)

Plutarch adds:

when on the fourth day of January he put out from Brundisium in pursuit of Pompey, though it was the time of the winter solstice, yet he crossed the sea in safety; for Fortune postponed the season. (De fortuna Romanorum 6; tr. F.C. Babbitt)

Napoleon Bonaparte’s summary account in his Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar is a little different from Caesar’s own. According to him,[1] Caesar dropped anchor “amid the rocks of Chimerium, in Epirus”.

Was this a mistake requiring correction? Napoleon wrote his Commentaries while in exile on the island of St Helena and in declining health, which would lead to his death in 1821. When his work is checked back against the original sources there are quite a few inaccuracies, particularly in relation to place names. Napoleon dictated the book to his faithful valet Louis-Joseph Marchand during pain-racked bouts of late-night insomnia in the muggy atmosphere of upland St Helena, and it seems that prior to publication in 1836 nobody verified the text.

However, the ancient coastal settlements of Chimera (Chimerium) and Palaeste lay close together in Epirus under the Ceraunian mountain range, so Napoleon was not mistaken about the location – he just used a slightly different description to Caesar. The site of Chimera is close to the island of Corcyra (Corfu), one of the Ionian Islands ruled intermittently by France between 1797 and 1814, so it is not surprising that Napoleon, who held power in France from 1799 to 1814, should have been familiar with the geography of the region.

The City of Chimera

Chimera is an intriguing name for a city, suggestive of the fabulous chimaera of Greek mythology, a deadly fire-breathing monster in the form of a lion with a goat’s head protruding from its back and a snake for a tail. However, it turns out that the Greek city of Chimera, established in about 300 BC on the shore of the Bay of Spile, has nothing to do with such a creature, and according to one theory may instead be named after χείμαρρος (cheimarros), which means “torrent”.

An unexpected reference to Chimera turned up in the Description of Greece by the indefatigable travel writer Pausanias (AD c.110–80). His Description covers southern Greece, but he sometimes mentions places further afield. While writing about Argos in the Peloponnese, he says (8.7.2):

Not only here in Argolis, but also by Cheimerium in Thesprotis, is there unmistakably fresh water rising up in the sea. (tr. W.H.S. Jones)

Pausanias was pretty strong on reporting the existence of potable water sources – a matter of no small importance to the ancient traveller through an often arid country such as Greece. Indeed his Description of Greece contains around a hundred passages describing springs of fresh water.

Pliny the Elder (AD 23/4–79) also mentions Chimera in his massive work Natural History (4.1):

On the coast of Epirus is the fortress of Chimaer, situate upon the Acroceraunian range, and below it the spring known as the Royal Waters. (tr. J. Bostock)

The Modern Town of Himara

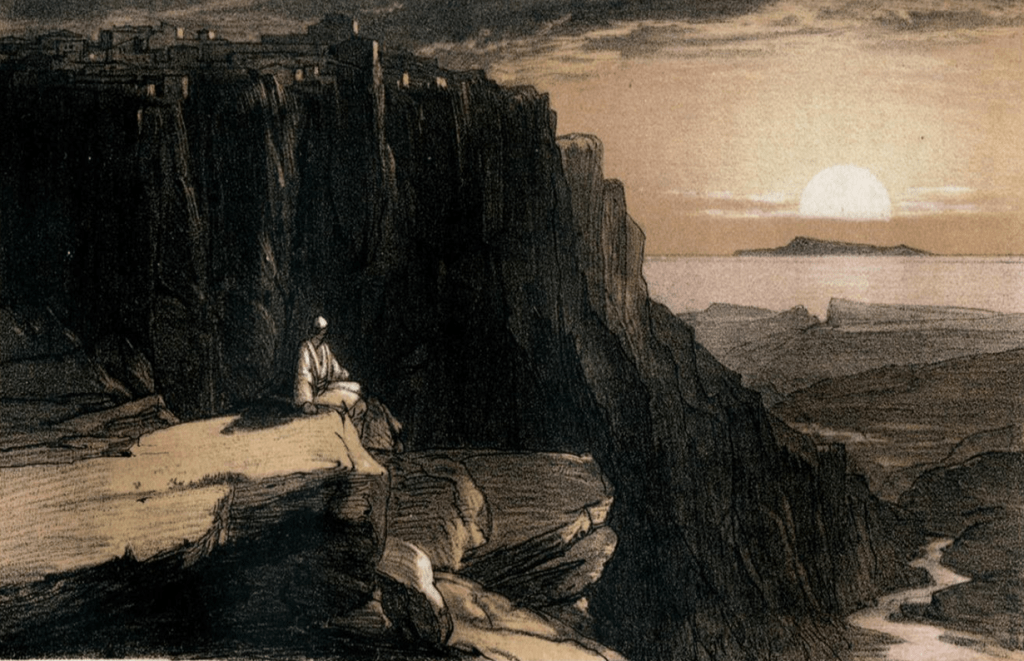

The city of Chimera is now known as Himara, or Himarë, located in southern Albania between the Ceraunian mountains to the northeast and the Ionian Sea to the southwest. The original walled city stood on a prominent hilltop about a kilometre inland, while the modern town spreads along the coastline of Spile Bay. Today, Himara is a popular beach resort on the Albanian Riviera.

The Waters of Himara

In 2022 the technical journal Hydrology published an article entitled “Karst Brackish Springs of Albania”.[2] Karst is a type of landscape in which groundwater occupies a multitude of underground channels and caverns, which form naturally in partially soluble rocks such as limestone.

The paper indicates that “submarine springs have been identified along the Himare coastal area”: there is a submarine spring discharging some 500 metres off Himara in the waters of the bay which is clearly visible in calm sea conditions. This must surely be the spring reported by Pausanias some 1,850 years ago.

And could Spile Bay be a candidate for Caesar’s “quiet harbourage”? It appears that the bay does not give safe shelter in stormy weather, but we know from Plutarch that the weather was particularly favourable when Caesar crossed from Brundisium.

On shore at the southern end of Spile Bay is the coastal spring of Potami which emerges just above sea level. Its substantial flow is collected in a concrete channel and used for the public water supply of Himara. One may readily suppose that the Potami spring is one and the same as Pliny’s Royal Waters, and this is confirmed in a modern paper on archaeological remains at Himara.[3]

There is something strangely satisfying about picking out an unexpected fact from Classical sources and being able to circle round and find it precisely validated in the present day.

The Spring of Dine

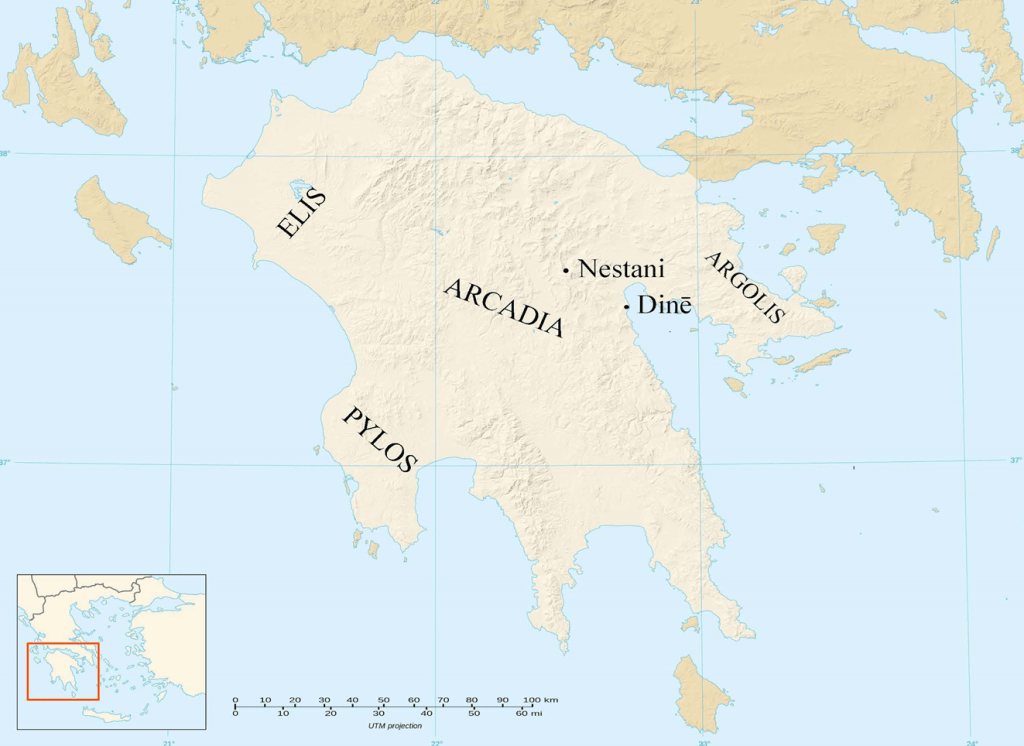

The other submarine spring mentioned by Pausanias in the passage above (8.7.2) is located in the isolated district of Arcadia in the east of the Peloponnese in southern Greece. Here is the full passage, ending with the sentence already given:

After crossing into Mantinean country over Mount Artemisius you will come to a plain called the Untilled Plain (Argon Pedion), whose name well describes it, for the rainwater coming down into it from the mountains prevents the plain from being tilled; nothing indeed could prevent it from being a lake, were it not that the water disappears into a chasm in the earth. After disappearing here it rises again at Dine. Dine is a stream of fresh water rising out of the sea by what is called Genethlium in Argolis. In olden times the Argives cast horses adorned with bridles down into Dine as an offering to Poseidon. Not only here in Argolis, but also by Cheimerium in Thesprotis, is there unmistakably fresh water rising up in the sea. (tr. W.H.S. Jones)

Dīnē (δίνη) means “whirlpool” or “vortex”. The submarine spring is still there, known as Anavalos Spring (Πηγές Αναβάλου, pēges anabalou). Anavalos roughly means “upwelling”.

William Leake (1777–1860), a traveller of the early 19th century, wrote of it as follows:

This is a copious source of fresh water rising in the sea, at a quarter of a mile from a narrow beach under the cliffs. The body of fresh water appears to be not less than fifty feet in diameter. The weather being very calm this morning, I perceive that it rises with such force as to form a convex surface, and it disturbs the sea for several hundred feet around. In short, it is evidently the exit of a subterraneous river of some magnitude, and thus corresponds with the Dine of Pausanias.[4]

The Underground River

Pausanias was perfectly correct about the source of the water which flows out at Dine. The Argon Pedion is a level plain enclosed by the Arcadian mountains. The plain is drained by a winding rivulet which disappears into a swallow hole or katavothra located in a cave below the hilltop town of Nestani – the chasm of Pausanias. The land used to be uncultivated because it regularly flooded when the inflow of rainwater exceeded the capacity of the underground channel. Such flooding still occurs every few years.

At Dine, 28 kilometres from Nestani, the water emerges from the seabed through three “eyes” in the rocky bed which are now enclosed by a modern concrete dam. This excludes seawater, meaning that relatively fresh water can be pumped out and used to irrigate farmland.

The water flows towards Dine at a substantial rate of around eight cubic metres per second, about the same as the total amount carried by the aqueducts which supplied the million inhabitants of Ancient Rome.

If, as seems typical, the water advances at a speed in the order of 100 metres per hour, it will take around a fortnight to cover the distance from Nestani to Dine. It follows that on average the multitudinous little channels and cavities through which the water percolates will have a combined cross-sectional area of several hundred square metres, set in a far larger expanse of rock. So while the underground river has a single entry point that we know of at Nestani and a combined exit at Dine, in between the water must soak through a garguantuan rocky sponge.

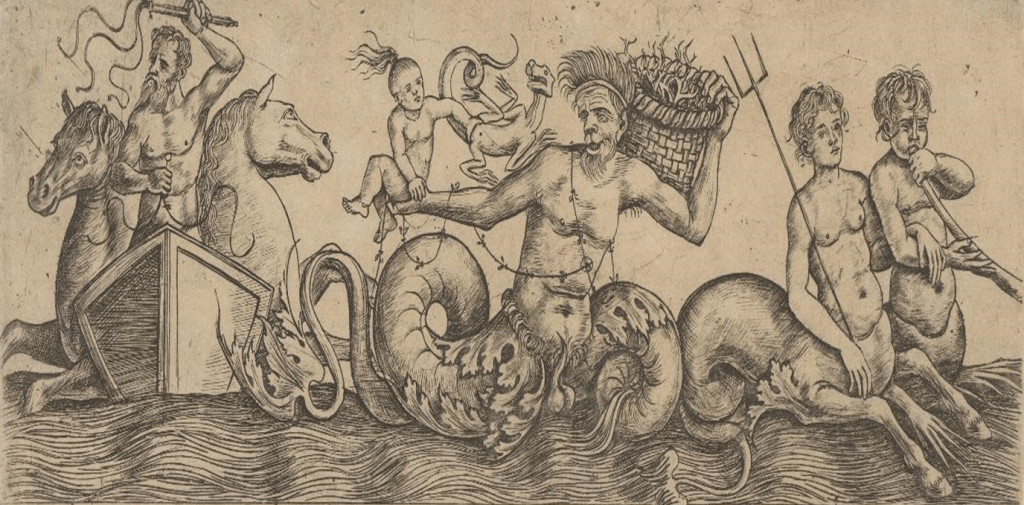

The Legend of Poseidon Genesius

The underground river from Nestani to Dine is central to a legend about the birthplace or genesis of Poseidon, the Olympian god known as “earth shaker”. In Arcadia he was venerated as a horse god and as a god of the waters who created springs with a strike of his trident. According to one version, when the goddess Rhea gave birth to Poseidon she had to hide him from his father Cronos who whenever she bore a son would eat the baby lest it become a threat to him. Rhea told Cronos that this time she had given birth to a foal; she hid the infant Poseidon in a sheepfold next to the sinkhole at Nestani in the care of the water nymph Arne. From there Poseidon was taken underground and reappeared at Genesion (Dine), where he was born for the second time. Poseidon is the father of the winged horse Pegasus whose name is derived from πηγή (pēgē), “spring”. The legend must account for the sacrifice of horses reported by Pausanias.

At another point (2.38.4) in his account. Pausanias makes a further mention of the place where the underground river discharges into the sea:

From Lerna there is also another road which skirts the sea and leads to a place called Genesium. By the sea is a small sanctuary of Poseidon Genesius. (tr. W.H.S. Jones)

Today, right by the sea and right alongside the outflow at Dine, is a little church dedicated to St George. Perhaps it stands on the site of the shrine to Poseidon Genesius.

The Poet Catullus

The myth of Poseidon employs the passage underground from Nestani to Dine as a metaphor for birth. Elsewhere in Arcadia, at Pheneus, there is another swallow hole draining a tract of land; the water later surfaces as the source of the River Ladon. From time to time, as writers ancient and modern have attested, the underground channel at Pheneus becomes blocked and the surrounding territory is flooded, sometimes for years, until the obstruction abruptly collapses and the water pours away.

The poet Gaius Valerius Catullus (c.84–54 BC) used this phenomenon to represent love overwhelmed by doom. In one of his poems (68b, 105–10) Catullus depicts the plight of the newly-wed Laodamia, who took her own life after her husband Protesilaus joined the war against Troy but, in fulfilment of a prophecy, became the first of the Greeks to step ashore and the first to die:

quo tibi tum casu pulcerrima Laodamia

ereptum est vita dulcius atque anima

coniugium. tanto te absorbens vertice amoris

aestus in abruptum detulerat barathrum

quale ferunt Graii Pheneum prope Cyllenaeum

siccare emulsa pingue palude solum.

So came your downfall, lovely Laodamia, when your husband, dearer to you than life and breath, was torn away from you. Engulfing you in a ruination of love the catastrophe dragged you down into a sudden-opened pit, like the chasm of the Greeks at Pheneus by Cyllene that empties the fertile wetland and parches the ground. (author’s translation)

The Island City of Aradus

Related to the submarine springs of Chimera and Dine is an account of a lead funnel being used to collect fresh water from a source on the seabed. The story originates in the Geography of Strabo (63/64 BC–c.AD 24) writing about Aradus (more recently Ruad) which was one of the main cities of Phoenicia. Aradus occupied a small island (still inhabited today) two kilometres off the coast of modern Syria in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was settled early in the 2nd millennium BC. According to Strabo (16.2),

Aradus… is distant from the land twenty stadia. It is a rock, surrounded by the sea, of about seven stadia in circuit, and covered with dwellings. The population even at present is so large that the houses have many stories. It was colonised, it is said, by fugitives from Sidon. The inhabitants are supplied with water partly from cisterns containing rainwater, and partly from the opposite coast. In war time they obtain water a little in front of the city, from the channel (between the island and the mainland), in which there is an abundant spring. The water is obtained by letting down from a boat, which serves for the purpose, and inverting over the spring (at the bottom of the sea), a wide-mouthed funnel of lead, the end of which is contracted to a moderate-sized opening; round this is fastened a long leathern pipe, which we may call the neck, and which receives the water, forced up from the spring through the funnel. The water first forced up is sea water, but the boatmen wait for the flow of pure and potable water, which is received into vessels ready for the purpose, in as large a quantity as may be required and carry it to the city. (tr. W. Falconer)

Pliny (NH 5.34) confirms this account, saying that the spring in the seabed lay at a depth of fifty cubits, or around 23 metres. This figure seems too large, though. It might be difficult to position the lead funnel over a spring at such a depth. Furthermore, modern charts show that today the sea between Aradus and the mainland is nowhere more than eight metres deep.

Dr William Smith’s magnificent Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, published in 1854, mentions Strabo’s account under Aradus and adds:

Though the tradition has been lost, the boatmen of Ruad still draw fresh water from the spring Ain Ibrahim in the sea, a few rods from the shore of the opposite coast.

A rod is an old English surveying dimension equal to 16½ feet, or about five metres.

This seems to suggest that the spring is quite close to the mainland. Today, the sea in the area is less than five metres deep as far as half a kilometre from the mainland, which sounds like more than “a few rods” distant from shore. I am inclined to suppose that though surviving manuscripts have Pliny give a depth of L cubitis altitudo maris or L cubita alto mari (“50 cubits sea depth”) he actually wrote V cubitis (“five cubits”, or 2.3 metres), which would seem to fit better in terms both of today’s geography and the feasibility of the operation. The other single-letter numbers one might consider are X (“10 cubits”, or about 5 metres) – which is perhaps too deep to fit Dr Smith’s comment – or I (“one cubit”, or 0.5 metres) – which seems too shallow to fit the description. One would probably not talk of letting something down from a boat to the bottom of the sea while operating in water barely knee-deep. Perhaps a sleepy monk in some draughty medieval scriptorium mistook the numeral V (or just possibly X) for L.

Aradus finds a further mention in the poem De Rerum Natura (6.890–4) by the Roman Epicurean philosopher Titus Lucretius Carus (c.94–55 BC):

genus endo marist Aradi fons, dulcis aquai

qui scatit et salsas circum se dimovet undas;

et multis aliis praebet regionibus aequor

utilitatem opportunam sitientibus nautis,

quod dulcis inter salsas intervomit undas.

In the sea at Aradus is a fountain of this kind, which wells up with fresh water and keeps off the salt waters all round it; and in many other quarters the sea affords a seasonable help in need to thirsting sailors, vomiting forth fresh waters amid the salt.

A Victorian traveller, Frederick Walpole (1822–76), spent a month on Ruad in 1850–1. He reported:

The people have no tradition of the island’s being supplied formerly from a marine spring, but they know of springs of fresh water, and I visited them, in the sea, half way between the main and Tartosa (modern Tartus, 4 km from the island to the north). In a line from one to the other, I found two springs excessively cold, the water at the surface brackish… Diving myself, the water seemed to spring from a sandy spot.[5]

It sounds as if Walpole’s springs may be distinct from the one described by Strabo and Pliny, though no doubt of a similar character. The sea in the area specified by Walpole is seven or eight metres deep today.

Lucius Aemilius Paulus in Macedonia

Between 171 and 168 BC Rome fought the Third Macedonian War against King Perseus which ended in a Roman victory at the Battle of Pydna. The Roman commander in the final year was Lucius Aemilius Paulus (c.229–160 BC), then serving as consul. At one point he encamped with his army on the Aegean coast of Macedonia but was troubled by a lack of fresh water.

According to Livy (44.33), Aemilius:

ordered the water-carriers to follow him to the sea, which was less than 300 paces distant, and to dig at short intervals from each other on the shore. The towering height of the mountains led him to expect that as no rivulets flowed from above the ground, they contained hidden streams which flowed as it were through veins into the sea and mingled with its waters. Hardly had the surface of the sand been removed when springs bubbled up, muddy at first and scanty, but they soon poured forth a clear and copious supply of water, as though it were a gift from the gods. (tr. A. McDevitt)

So Aemilius perceptively deduced the presence of submarine springs and by good fortune was able to intercept them by dint of a little digging on the beach. Evidently he met the requirement supposedly laid down by Napoleon, that a good general must be lucky as well as skilful.

From Alpheus to Arethusa

One other subsea spring is particularly well known, though its story is of more doubtful authenticity. The Fountain of Arethusa is a natural spring on the island of Ortygia located in the harbour of Syracuse in Sicily that still flows today. According to Greek mythology, this freshwater fountain was the place where the nymph Arethusa returned to the earth’s surface after fleeing through the underworld from her home in Arcadia, hotly pursued by the amorous river god Alpheus.

It was accordingly believed that the River Alpheus of the Peloponnese passed under the sea and reappeared in the fountain of Arethusa: a goblet was said to have been thrown into the river in Greece, and to have reappeared in the Sicilian fountain over 500 kilometres away. After learning about the underground river running almost 30 kilometres from Nestani to Dine, the undersea course of the Alpheus no longer seems quite so far-fetched.

The Poet Homer

The Alpheus figures in Homer’s Iliad (11.728) when the aged King Nestor of Pylos recounts a successful exploit of his youth from a war over cattle between Pylos and the neighbouring state of Elis in the west of the Peloponnese. Before the crucial battle the men of Pylos parade in fighting order beside the River Alpheus which runs between the two territories. There they sacrifice a bull to Alpheus, another to Poseidon and a cow to Athena.

The Poet Coleridge

Today’s River Alfeios and its tributaries disappear several times into the limestone of the Arcadian mountains and reemerge after flowing some distance underground. The river was part of the inspiration for Kublai Khan by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834):

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean.

Robin Alington Maguire is a former civil engineer and banker with a longstanding interest in ancient history and culture who likes to seek out new deductions from fragmentary ancient sources. He has translated and edited Napoleon Bonaparte’s Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar (Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2018). His earlier essays for Antigone argued that Cicero should have taken a different tack during the Catilinarian Conspiracy of 63 BC, reconstructed the rations supplied to the crews of Athenian trireme warships, and examined Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon.

Further Reading

Most of the sources quoted in this article are readily accessible online, and links to these are supplied where available. The 19th-century writers often make striking reading and sometimes seem more remote from the present day than Pliny or Pausanias.

Notes

| ⇧1 | N. Bonaparte, Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar, tr. R.A. Maguire (Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2018) 63. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | The work of R. Eftimi, M. Parise and I.S. Liso in Hydrology 9.7 (July 2022). |

| ⇧3 | K. Çipa, “Himara in the Hellenistic period: analysis of historical, epigraphic and archaeological sources,” Novensia 28 (2017) 65–78, at 68. |

| ⇧4 | W.M. Leake, Travels in the Morea (London, 1830) 480. Morea is an old word for the Peloponnese. |

| ⇧5 | F. Walpole, The Ansayrii or Assassins with Travels in the Further East in 1850-51 (Richard Bentley, London, 1851) Vol. 3, 389. |