Jaspreet Singh Boparai

Part I of this essay can be read here, and Part II here.

Marie-Henri Beyle (1783–1842) only took on the pen name ‘Stendhal’ in 1817, for reasons that remain obscure. Unlike Chateaubriand, Stendhal idolised Napoleon with surprisingly little reservation until late in life; the fact turns out to have some bearing on Stendhal’s ever-shifting attitudes towards ancient literature and the classical tradition.

We can rarely trace direct classical influences on Stendhal’s fiction, in part because he did not want to write like Chateaubriand, or pepper his prose with learned allusions and self-conscious name-drops of the sort that authors make when they want to draw attention to their relationship with the classical tradition. Also, he wrote his novels so fast that he simply did not have time for that sort of thing: he dictated his masterpiece La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma) in under two months, beginning on 4 November 1838, and ending on 26 December. This is not a short novel, nor does it bear many evident traces of haste.

His other great novel Le Rouge et le noir (The Red and the Black, or Scarlet and Black as the old Penguin Classics translation calls it) was conceived on the night of 25 October 1829, and published on 15 November 1830; but there were numerous interruptions in the composition. He seems to have tried to start writing in earnest on or around 22 January 1830; at that point the novel was called Julien, and was allegedly the story of “a young provincial who is a student of Plutarch and Napoleon”. The Plutarchan element is of special importance here, because Plutarch ends up being especially useless as a guide for how to become a great man in the modern world.

The hero of The Red and the Black, Julien Sorel, is the ambitious, dreamy son of a carpenter who worships Napoleon and has memorised the entire New Testament in Latin. This feat serves him in good stead: it wins him protectors among the clergy; he ends up in the great seminary at Besançon, where the local bishop is so impressed that he gives Julien a valuable copy of Tacitus as a gift. Not only has Julien not read any Tacitus: he has never even heard the name.

The Red and the Black is not an autobiographical novel; Julien Sorel is not a self-portrait. People with no talent who nurse lifelong grudges about their frustrated creative ambitions (that is to say, a majority of academics who work on literary subjects, and virtually every single teacher of institutionalised ‘Creative Writing’ you have ever met) often have the unfortunate habit of assuming that all fiction is really just some form of therapeutic exercise, rooted more or less uncomplicatedly in the writer’s life – because this is what their own novels are like. But Stendhal, unlike Chateaubriand, is more inventive than that. His attitude towards Latin is certainly not that of Julien Sorel.

Like Chateaubriand, Stendhal is an engagingly unreliable memoirist; he has the added attraction, however, of making up pseudonyms for himself, deliberately altering verifiable facts, and playing self-conscious games with the truth, for the fun of it perhaps, rather than out of any compulsion.

His longest exercise in autobiography is The Life of Henry Brulard, which was written at the usual high speed between 23 November 1835 and 26 March 1836 before he abandoned the manuscript, for whatever reason. This memoir provides an even better glimpse of Stendhal’s relationship to classical antiquity than his travel diary Promenades dans Rome (1829), in which the ancient world is often overshadowed by the modern city, or more recent history, or simple gossip. But Henry Brulard begins the other way round.

The narrative begins in Rome, on the Janiculum, on 16 October 1832, in front of the church of San Pietro in Montorio, which features the famous ‘Tempietto di Bramante’ (1502), which was built to mark the site where Saint Peter was martyred. The monument is impressive even if you hate the Catholic Church as much as Stendhal did. ‘Henry Brulard’ takes note of all the Christian, mediaeval and Renaissance monuments around him, but wants to look past them, to see the foundations beneath; thoughts of Livy, Hannibal and ancient Rome overtake him; he has the idea to examine his own life.

Even here he cannot resist a side-swipe at François-René de Chateaubriand, whom he sneers at as an ‘egotist’. A fellow-egotist, one might say. But (according to the dates in the manuscript) he does not set about writing down his memories in earnest for another three years.

A Classical Education

The Life of Henry Brulard seems basically reliable, at least where some areas of Stendhal’s life are concerned. His hated father had a good classical library; his grandfather’s was even better, and boasted an edition of Pliny with French translations on facing pages in which the teenaged ‘Henry Brulard’ searched in vain for useful information on women. His grandfather had taught him how to love Horace, Sophocles and Euripides; and yet it is not clear that Stendhal (or ‘Henry Brulard’) knew very much Greek. He read his beloved Plutarch in French.

‘Henry Brulard’ talks at length in this memoir about Latin, and how badly he was taught it, from the age of seven onwards. He hated Latin verse composition, and the Gradus ad Parnassum lexicon; on the other hand, he fondly remembers translating passages from Ovid and Vergil, and Tacitus’ Life of Agricola at the Central School in Grenoble, in between getting into fights, and despairing at the quality of instruction in mathematics, which was an essential subject for a future soldier. You do sometimes wonder how much Latin literature he actually sat down and read over the course of his life.

After leaving school at seventeen, Stendhal spent most of his life variously as an army officer and a civil servant, with long spells as an idle café intellectual and habitué of salons (there is no way to say these things unpretentiously in English). He read widely, frequented theatres, concerts and operas, took lessons in dancing and Classical Greek, tried to write Molière-style comedies, and enjoyed energetic social, intellectual and love lives, all whilst serving in the Sixth Regiment of Dragoons in Napoleon’s Grande Armée (although he sometimes went on extended periods of medical leave, having first contracted syphilis at the age of nineteen or so).

Stendhal survived Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign in 1812, and spent the years from 1814 to 1821 mainly in Italy, where he began his literary career in earnest, and developed an extraordinary eye for art. His 1817 History of Painting in Italy is shoddily researched, written with a combination of laziness and impatience, and marred by outrageous plagiarism; yet the work deserves a full translation into English, because his brilliance so frequently shines through in his speculations on the nature of painting, beauty and the correct attitude towards Ancient Greek sculpture.

As a writer Stendhal consciously developed a soldier’s prose style, with a clear, hard, classical simplicity redolent of Caesar: he loathed Cicero. There is something curiously Nietzschean about his art criticism: his History of Painting develops a theory of how the transition from Archaic to lassical to Hellenistic Greek sculpture reflects an advancing civilisation, as the gods develop and evolve from figures of retribution to expressions of paternal benevolence.[1]

His views on ‘classicism’ were shaped by his experience of Italian Renaissance art, the best of which was always painted in a manner that seemed not only appropriate to the time, place and atmosphere of its creation, but also reflected particular conceptions of happiness. In his 1822 treatise on love, he would famously claim that beauty is a promise of happiness. He was never in danger of embracing any kind of virtuous austerity, of course; but once he articulated this concept to himself, he became decisively immune to the kind of ascetic Roman Republican ideals that even Chateaubriand still found seductive in old age from time to time.

Against ‘Classicism’

Being a former soldier, Stendhal keenly appreciated Roman engineering, and the practical elements of Roman architecture, almost as much as he enjoyed Greek and Roman history, and books like Montesquieu’s aforementioned Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness and Decadence of the Romans. He resisted all approaches to aesthetics that ignored or downplayed the realities of life in favour of various dubious forms of ‘refinement’, which seemed to him mere vanity.

He was hilariously scathing about Johann Winckelmann (1717–68), the historian of Ancient Greek and Roman art whose books revitalised neo-classicism throughout the second half of the 18th century, and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–81), whose essay Laocoön (1767) argued vehemently against Winckelmann’s positions, but was in its way perhaps equally influential on writers, if not artists.

To Stendhal the two men represented two sides of the same coin – a word-based, intellectualised approach to ancient art that manifested itself in pseudo-poetic rhapsodies that had little to with nature, or the art that was attempting in some way to reflect or illuminate it.

What Stendhal thinks of as ‘classicism’ is really what we would call ‘neo-classicism’, particularly as manifested in poetry and stage plays. He was annoyed when writers tried to create ‘timeless’, ‘universal’ work, and believed that taste was probably contingent rather than absolute:

The world of letters recognises more than one genre, whose present enchantment is not to be denied, yet which, three or four centuries hence, will be nought but ashes. Lucian is as boring today as [Voltaire’s] Candide may likely be in the year AD 2200. And still the academic mind insists that literary merit must be judged, not by the intensity of the pleasure it affords, but by its mere persistence. (From Richard N. Coe’s 1959 translation of Stendhal’s Rome, Naples and Florence.))

The works of Lucian of Samosata (c.AD 125–80) are an excellent example of classical texts that are not really ‘classic’, but parasitic in a sense on the virtues of ‘genuine classics’. As with Voltaire’s works, they boast a superficially ‘elegant’ style, and little else. Their main use is in teaching fledgling Hellenists how to read Greek prose so that they can move on to better authors. They are ‘classics’ only with respect to Greek prose composition classes.

Of course, Candide (1759) went stale rather faster than Stendhal predicted: since the Second World War, it has joined the novels of George Orwell (1903–50) and Albert Camus (1913–60) as a purported favourite of ‘intellectuals’ who do not in truth read very much, but wish to be considered ‘cultured’ all the same. Stendhal outgrew his taste for this sort of triviality in his forties, as he began to meditate his own great works to come.

Chapter 115 of Stendhal’s History of Painting provocatively suggests that ‘classical beauty’ is incompatible with modern feeling, and ends with the rhetorical question: if classical beauty is an expression of strength, reason and prudence, then how will it manage to depict a scene which moves us precisely by the absence of these virtues? His obvious conclusion sounds rather un-Nietzschean: the modern world has no need of ‘classical’ virtues. But then he develops his notions of new, modern ideals that do indeed sound Nietzschean, and even somewhat ‘classical’. Stendhal always plays this game of destruction and reconstruction, when he is thinking aloud and theorising ‘on the fly’.

He never loses sight of Classical Greek examples; what he finds objectionable are fossilised interpretations and reactions that have been learnt by rote, and that parrot the opinions of perceived authorities, particularly ‘academic’ ones (by which he means, in this context, professors of fine arts at one of the state-subsidised art schools; when he is talking about literature, an ‘academic’ is a member of the French Academy, the official body that is responsible for creating a dictionary of the French language).

Stendhal’s anti-‘classicist’ provocations in his History of Painting really amount to a plea for intelligent use of ancient precedents: indeed, all of this is a lead-up to his life of Michelangelo (1475–1564), whose work is hardly a rejection of the Graeco-Roman tradition – his oeuvre is a powerfully convincing reassertion of ancient virtues in a post-‘classical’ world.

All this forms the background to Stendhal’s blistering anti-‘classicist’ criticisms of the Salon (or official art exhibition) of 1824, which is too often selectively quoted in dishonest attempts to assert the opposite of what Stendhal is trying to say:

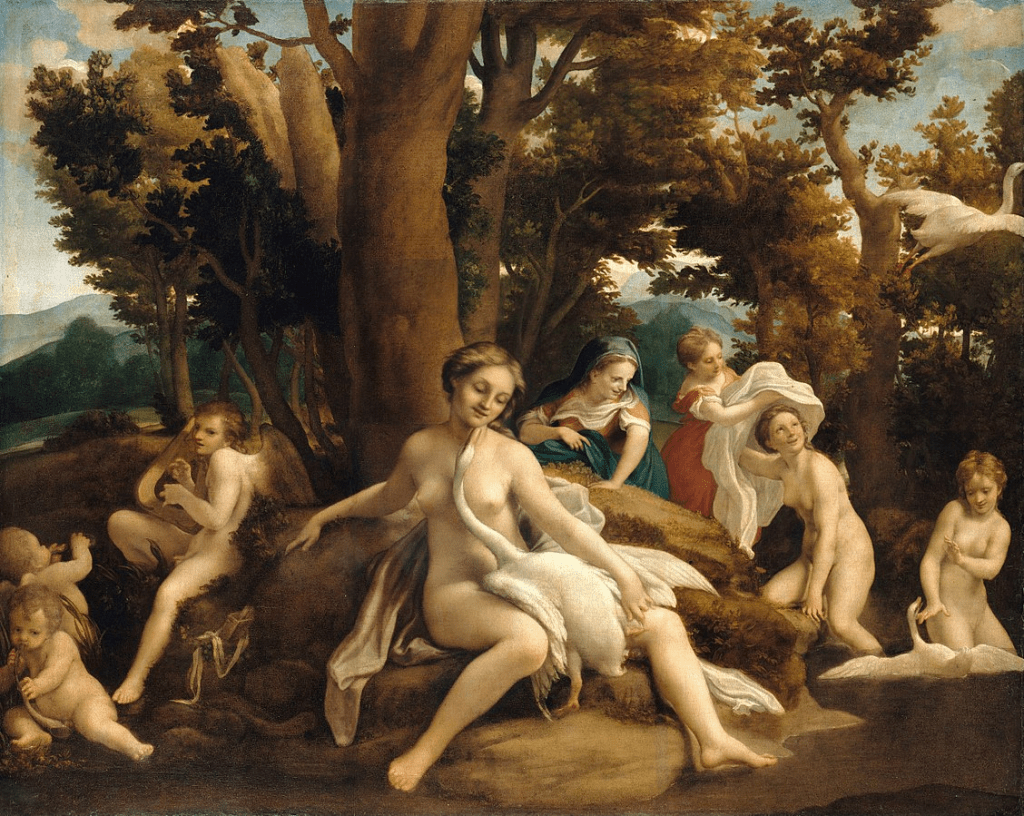

We are on the eve of a revolution in the fine arts. Large pictures consisting of thirty naked figures copied from classical statues, and cumbersome five-act tragedies in verse, are doubtless highly estimable works. But whatever people say, these are beginning to bore us, and if the Sabines [of Jacques-Louis David] were shown today, the figures would be found passionless, and people would consider it ridiculous to march into battle without clothes on. ‘But this is normal in classical bas-reliefs!’ protest the classicists of art, those men who swear by nothing but David, and never pronounce three words without speaking of style. And what do I care about classical bas-reliefs? We must try to do good modern painting.[2]

The entire essay is worth studying, if you can find an unexpurgated copy. Sometimes passages like these are taken out of context by lecturers in art schools who seek systematically to perpetuate the various falsehoods that have all but destroyed basic technical competence in the arts since the Second World War – by those who seek to replace visible, recognisable beauty with the visual equivalent of the plinky-plonk music that ‘experimental’ composers have inflicted for over a century on a masochistic public that will willingly suspend all common sense and gut instinct because it is so desperate to be thought of as ‘enlightened’ or ‘avant-garde’ (a French term best rendered into English as ‘dupe’, ‘sucker’ and/or ‘useful idiot’). But Stendhal is not a philistine.

The Romantic Problem

As with so many artistic geniuses, Stendhal bothered little about being consistent or coherent in his more theoretical writing. He developed concepts, not for their own sake, or the pleasure of discussing them, but as a means of messily thrashing out an intellectual basis for his creative work.

After the fall of Napoleon, and the Bourbon Restoration in 1814–15, Stendhal saw that the more conservative and reactionary writers and artists of the period were often not even aware that they what they were creating was stale, out of date, and unattractive to much of their audience. He had not figured out what a ‘Romantic’ was; all he knew was that something new was taking shape, and most of the influential critics, academics and other literary figures of his time could not even see what was going on, let alone understand it. But he himself did not have the language to describe it, which is part of the reason why so much of his criticism sounds like proto-Nietzsche: take this passage, from Racine and Shakespeare:

It requires courage to be a Romantic, because one must take a chance. The prudent Classicist, on the contrary, never takes a step without being supported, secretly, by a line from Homer or a philosophical comment made by Cicero in his treatise De Senectute. It seems to me that the writer must have almost as much courage as the soldier: the former must give no more thought to the journalists than the latter gives to the hospital.

The snide reference to De Senectute (On Old Age) is obviously rhetorical: Stendhal paints his opponents as out-of-touch old men, and declaring himself on the side of youth. Yet classical literature was, as we have seen, not merely fogeyish in his eyes. Rather, the world after the Revolution and Napoleon needed a fresh approach, and a renewed vision of ‘greatness’ that swept away the unnecessary accretions of 18th-century ‘classicism’, which was (for Stendhal) tainted by associations with Louis XV, Louis XVI, and all the obsolete institutions that helped prop up the pre-Revolutionary monarchy.

Stendhal rejected Chateaubriand’s ‘poetic’ and ‘literary’ approach to the classical tradition; his idea was to learn instead from ancient historians. Not necessarily Herodotus, whom he does not seem to have mentioned, or Thucydides, whom he may not have read even in translation, but Polybius, Livy, Tacitus, Herodian and – above all – Plutarch.

Yet Stendhal’s one conscious attempt at creating work on a classical model is a failure. The failure is all the more interesting because it almost seems like the book he was born to write.

In November 1836, Stendhal began to compose his long-meditated life of Napoleon.[3] He had an earlier stab at it in 1817/18, but evidently he did not have his thoughts in order yet, and could not separate his hero-worship from his disappointment at Napoleon’s failures. This first attempt seems to have been initially conceived as a pastiche of one of Plutarch’s Lives, in structure and style. But you can watch Stendhal gradually lose confidence in his work, as his material begins to slip out of his grasp, and the imperfections in his conception begin to make themselves known. He also begins to lose faith in his hero, and seems to be as shocked as the reader is by Mariano Luis de Urquijo (1769–1817), a Bonapartist statesman.

In a letter to General Gregorio García de la Cuesta (1741–1811) dated 13April 1808, Urquijo recounts an encounter he had with ministers of the Spanish king, during which he hinted that it would be very easy for Napoleon to abolish the Bourbon dynasty in Spain and establish a French sovereign. The king’s second son interjected, aghast: could a hero of Napoleon’s stature really do something so vile, when the king had placed himself in Napoleon’s hands in good faith? Urquijo advised the young royal to re-read Plutarch: there he would find that the heroes of Greece and Rome achieved their glory on the backs of thousands and thousands of piled-up dead bodies; but of course people forget about all of that and look instead at the glorious end results, with combined awe and respect.

The quoted letter goes on; Stendhal’s uneasiness is palpable. But even when he recovers his nerve, he clearly sees that a pseudo-Plutarchan biography would prove embarrassingly anachronistic. He has not really thought through his approach: throughout the 1817/18 manuscript he repeatedly compares Napoleon to Caesar and Alexander, in the vague way that everybody else does; but he cannot find a way to reconcile his admiration for Napoleon’s genius, and mixed feelings about the Napoleonic myth, with judicious criticism of Napoleon’s faults, and errors.

The problem with Plutarch’s approach, from a modern point of view, is that it was intended purely to enable evaluation of character through narrative and anecdotes: you cannot really deal with legislative or administrative issues, or anything else that interrupts the telling of a story. This is why historians despair when Plutarch is their only major source for a given event. Formally, a Plutarch-style biography can only deal with Napoleon’s accomplishments as a general, and some of his personal life. But we know too much about him to find this satisfactory.

Stendhal’s second attempt to write about Napoleon’s life is at once richer and more confused. In an undated prefatory note addressed to prospective publishers, he compares his style to that of the Plutarch-obsessed essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–92), and the 18th-century linguist, classicist and general polymath Charles de Brosses (1709–77, known commonly as the Président de Brosses), whose pioneering 1760 study On The Worship of Fetish Gods remains celebrated today as a landmark in the history of anthropology.[4] But presumably Stendhal was referring to the Président de Brosses’s wittily indiscreet private letters from the 1740s that were published almost a century later, and became a great success. In any case, the note is enigmatic, to say the least.

In a preface written for himself (13 February 1837) Stendhal criticises modern historians’ affectation of impartiality, in the manner of Sallust, and claims to leave the reader to make up his own mind. He will do no such thing: his second attempt at a preface (April 1837) is combative, with most of the aggression directed against the elegantly impersonal ‘academic’ style, which he regards as conducive to lying.

He claims to have found a simpler, more honest style in 17th-century translations of ancient texts – the letters of Pliny the Elder, as rendered into French by the Bible translator Fr Louis-Isaac Lemaistre de Sacy (1613–84), and Herodian’s history, in the version of the theologian Fr Nicolas-Hubert de Mongault (1674–1746).

How seriously are we to take such an assertion? The opening paragraph of the Mémoires sur Napoléon includes an interesting slip:

I feel a sort of religious emotion in daring to write the first line of the story of Napoléon. It concerns the greatest man to have appeared in the world since Caesar, and even if the reader has taken pains to study the life of Caesar in Suetonius, Cicero, Plutarch and [Caesar’s own] Commentaries, I daresay that we are about to go together through the life of the most astonishing man to have arisen since Alexander, about whom we do not know enough details to be able to judge how difficult his undertakings were.

Stendhal is so overwhelmed by ‘religious emotion’ that he cannot make up his mind as to whether he wants to compare Napoleon to Caesar or Alexander. In this text, all of Stendhal’s own contradictions and mixed feelings find expression: he does not even know what he feels about his subject anymore, or why he is writing this biography. He has come to understand that Napoleon betrayed the ideals of the Revolution, and became a despot. Yet he still cannot let go of his admiration.

In April 1837, Stendhal abandoned his Napoleon manuscript after six months’ work. He was less than halfway through the project, and had lost all control. Its failure had two obvious consequences. First, it enabled Stendhal to transform his divided feelings about Napoleon into those of Fabrice del Dongo, the young hero of The Charterhouse of Parma, who runs away from home to take part in the Battle of Waterloo. Amidst the chaos of the French army’s defeat, he tramps through the mud looking for Napoleon, whom he never finds. The symbolism of this section of the novel tells us far more about Stendhal’s ultimate attitudes than either of his stillborn Napoleonic biographies.

The second consequence of the biography’s implosion: Stendhal came belatedly, and grudgingly, to recognise the value of the balanced, elegant, superficially ‘impartial’ ‘classicism’ that he had attacked so vehemently for two decades. Its form, structure and style might have saved him six wasted months, and helped him organise and discipline his thoughts about Napoleon.

But by this point in his life, it was too late for him to change course. He was not a biographer: he only really knew how to develop ideas in the form of fictional narratives, and to do so successfully, he had to be at least a little bit out of control. In the end, Stendhal did not have it in him to be a real ‘classicist’ in form, style or disciplined self-control. On the other hand, he seems to have relied on the Muses’ inspiration even more than the hated Chateaubriand did.

Stendhal was a friend and literary mentor to the writer Prosper Mérimée, (1803–70) who is of course best-known for his 1845 story Carmen (the basis for the famous opera); his novella The Venus of Ille is of interest to Classicists as arguably the best story ever written about archaeology. We mention him because of a passage in his 1850 reminiscence of Stendhal that seems to sum up Stendhal’s attitude towards the more fastidious types of ‘classicism’:

When he saw that I was revisiting Greek at the age of 25, he mocked me: “You’re on the battlefield already. It’s not time to polish your rifle: it’s time to fire.”

Part IV of this essay series can be read here.

Jaspreet Singh Boparai recently abandoned academia to cultivate the Muses. He has previously written for Antigone on Tacitus and the thrill of writing here, on the challenges of translating (pseudo-)Latin here, on the pleasures of Poussin here, on Neo-Latin syphilis here, on Apuleius the ‘witch’ here, on V.S. Naipaul and Latin here, and on the Classics and British India here.

Further Reading

Stendhal

You should read as much Stendhal as you can: if you have A-Level, International Baccalaureate or an equivalent level of French, then you should do so in the original, beginning with the Chroniques italiennes (1829–39, first collected under this title in 1855).

Whether you begin your experience of Stendhal’s novels with The Red and the Black (1830) or The Charterhouse of Parma (1839) is up to you, as long as you are willing to accept that you will prefer the one you read first, whichever it turns out to be.

The best selection in English from Stendhal’s correspondence is To The Happy Few: Selected Letters of Stendhal (Grove Press , New York, USA, 1952). Norman Cameron translates with notable verve. In 2011, Hesperus Press published a selection entitled Letters to Pauline, edited and translated by Andrew Brown, with a witty foreword by Adam Thirlwell. This is easier to find than the Grove Press edition, which deserves to be reprinted.

Calder Publications has reprinted the 1962 edition of Stendhal’s Racine and Shakespeare (translated by Guy Daniels), as well as Richard N. Coe’s 1959 rendering of Rome, Naples and Florence, and many others besides. Order these attractive volumes from Alma Books.

John Sturrock’s translation of The Life of Henry Brulard was republished in 2002 in the wonderful New York Review Books Classics series (which really ought to reprint Norman Cameron’s selection of Stendhal’s letters, not to mention David Wakefield’s splendid 1973 anthology Stendhal and the Arts, which was published by Phaidon, and collects a great deal of writing that seems otherwise available only in French).

‘The German Stendhal’

As was mentioned in the first footnote, Stendhal was evidently regarded by some French nationalists as a sort of French equivalent to Friedrich Nietzsche. There is also the vague idea that Joseph de Maistre (the subject of our fourth and final essay in this series) was in some sense the Catholic equivalent (or pre-emptive answer) to Nietzsche.

It seems that Nietzsche is alas unavoidable, even in discussions of 19th-century French literature that has nothing to do with him, and was written before he was born.

Classicists too often limit their acquaintance with Nietzsche purely to The Birth of Tragedy (1872) and then attempt to extrapolate from their vague impressions of this work. You might have a fairer, clearer idea if you begin with his Untimely Meditations (1876), and then proceed to Twilight of the Idols (1888), which opens with a very funny attack on Socrates. After these you may proceed further, or else decide that your time might be better spent.

For the casual reader, the best translations of Nietzsche into English would appear to be those by R. J. Hollingdale; the Penguin Classics editions are in general just as good as the (somewhat more expensive) ‘Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy’ editions from Cambridge University Press. Yet Hollingdale’s A Nietzsche Reader (Penguin Classics; first published in 1978) seems better as a classroom anthology than an introduction for interested non-specialists.

Stanford University Press is currently publishing Nietzsche’s complete works in English translation. I have only seen the eighth volume (Beyond Good and Evil/On the Genealogy of Morality, translated by Adrian Del Caro, 2014), but on the evidence of Professor Del Caro’s work here it seems that the editors of this series, Professors Alan D. Schrift and Duncan Large, have maintained very high standards indeed. Perhaps the main reason to recommend the Penguin or Cambridge editions first is that they are more frequently stumbled across in bookshops.

Notes

| ⇧1 | I have no taste for the work of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), but do not mean to say “curiously Nietzschean” as an insult to Stendhal; it is merely a description that seems to me accurate. Undoubtedly there are sometimes parallels between the two men’s work. Indeed, in the early 20th century, Stendhal was seen by some French intellectuals as “our Nietzsche”, or “the Nietzsche of our race” (!); for an introduction to the circumstances leading to this bizarre-sounding assertion, see Christopher Forth’s interesting article “Nietzsche, decadence and regeneration in France 1891–1895” in The Journal of the History of Ideas 54.1 (January, 1993) 97–117. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | The only English translation I have found of this text is in David Wakefield’s Stendhal and the Arts (Phaidon Press, London, 1973). Wakefield’s anthology is exemplary, and deserves to be reprinted; Stendhal has always been too little appreciated in the English-speaking world for his gifts as a connoisseur, and shrewdness as an art critic. |

| ⇧3 | These comments are based on Catherine Mariette’s 1998 edition of the relevant texts, published under the title Napoléon: Vie de Napoléon; Mémoires sur Napoléon. |

| ⇧4 | There is little in English on the Président des Brosses; perhaps the best short introduction in English to the man and his work will be found in Marc Fumaroli’s The Republic of Letters (2018; mentioned in the “Further Reading” section to Part I of this series). |