Jaspreet Singh Boparai

Why Should She Read Plutarch?

In the spring of 1800, Marie-Henri Beyle (1783–1842), the man who would later be celebrated as ‘Stendhal’ – one of the three greatest French novelists of the 19th century – was seventeen years old, reluctantly serving as a secretary to his cousin whilst entertaining grander ambitions.

On Sunday, 9 March of that year, he wrote to his beloved sister Pauline (1786–1857) with hints on where to find pleasure in literature and the arts:

I advise you to try to read Plutarch’s Lives of the Great Men of Greece: when you are further advanced in literature, you will realise that it was the reading of this work which formed the character of the man who possessed the finest soul and greatest genius of them all, J.-J. Rousseau. You might read Racine and the tragedies of Voltaire, if you are permitted: ask grandfather to read you [Voltaire’s] Zadig in the same way as he read it to me two years ago. I think it would also be a good idea for you to read [Voltaire’s] Le Siècle de Louis XIV, if nobody objects. I know what you will say: “What a lot of reading!” But, my dearest girl, it is by reading thoughtful works that one in turn discovers how to think and feel.[1]

A month later (Thursday 10 April) he wrote again, wondering why his sister had not replied to the last letter, reminding her that there was no need to draft and re-draft her words:

That’s the silliest folly that can possess one, because to have a good epistolatory style, one must write exactly what one would say to the person if one saw him, only being careful not to write down repetitions to which, in conversation, a tone of voice or gesture might give some value. Have you started on [Jean-François de] La Harpe? I suppose you have, but I expect you haven’t dared to tackle Plutarch: nevertheless you would do well to read him. You’ll find in him the very picture of the daily life of the ancients, and that is most essential, because people are always talking about it, and talking about it very foolishly. In due course, and when you have finished Plutarch, you will be able to read [Charles-Albert] Demoustier’s Lettres à Émilie sur la Mythologie…

If only we all had big brothers like that (except for the recommendations of Voltaire’s justly-forgotten tragedies – then again, our man was only seventeen at the time). But did Stendhal’s views on Plutarch change? When he was 40, he published Racine and Shakespeare (1823), one the most celebrated polemics in the history of French literature. In the third chapter, “What Romanticism Is”, he sets out an unflattering definition of ‘classicism’:

‘Romanticism’ is the art of presenting to different peoples those literary works which, in the existing state of their habits and beliefs, are capable of giving them the greatest possible pleasure. ‘Classicism’, on the contrary, presents to them that literature which gave the greatest possible pleasure to their grandfathers.[2]

We thought Stendhal and his sister liked their grandfather. Read their letters: they did; and they even shared his tastes in literature; but evidently Stendhal is talking about something else here:

Sophocles and Euripides were eminently ‘romantic’. To the Greeks assembled in the theatre of Athens, they presented those tragedies which, in accordance with the moral usages of that people, its religion and its prejudices in the matter of what constitutes the dignity of man, would provide for it the greatest possible pleasure.

To imitate Sophocles and Euripides today, and to maintain that these imitations will not cause a Frenchman of the nineteenth century to yawn with boredom, is ‘classicism’.

So ‘classicism’ does not necessarily involve what we would call ‘classical texts’, or the ‘classical literature’ in Greek and Latin that delighted Stendhal’s deeply learned grandfather. Then what precisely is he talking about?

Stendhal’s opinion matters: he happened to be one of the three greatest French novelists of the 19th century, along with Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) and Gustave Flaubert (1821–80). That is to say, he was a genius – one of the rare modern writers whose work enjoys genuinely ‘classic’ status. But what does that mean? What relationship does his work have to ‘real’ classical literature – to that body of Greek and Latin texts that begin in the Archaic Era with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and the poems of Hesiod, and ends shortly after the Fall of Rome with Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (AD 524) and, though it may stretch the definition of literature somewhat, the Codex Justinianus (AD 529)?

What is this ‘Classical Tradition’?

We use the term ‘the classical tradition’ to describe how elements of Ancient Greek and Roman culture managed to survive the passage of time, or be consciously revived or renewed. The term is used vaguely, as is ‘classical reception’, which often denotes individual instances of this process, often by those who are hostile, for whatever reason, to this notion of a ‘tradition’.

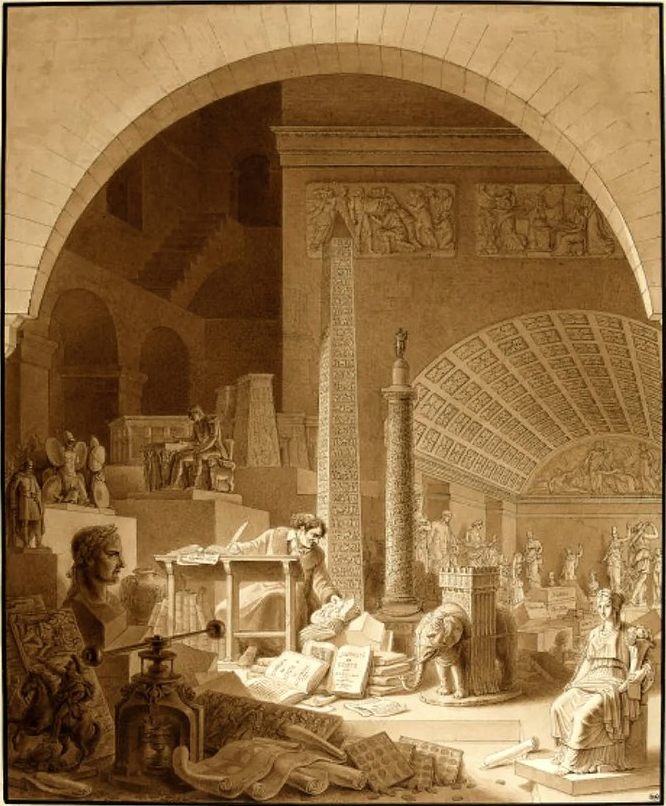

Whatever ‘the classical tradition’ is, it deserves study, not as a distraction from Greek or Latin language or literature, or Greco-Roman culture, but in order to understand the precise ways in which our own approaches to the ancient world come invariably mediated through later ‘cultural products’. How could they be otherwise? It takes years to master the classical languages adequately enough for something that feels like direct access to antiquity. To go through that process willingly, you need somehow to trust that it will be worth all the effort. This is where art and literature come in.

Intellectual historians may broadly elucidate aspects of how we come to know ancient civilisation, and why perceptions of our Greek and Roman heritage might shift, develop and evolve from place to place or time to time; students of ‘classical reception’, by contrast, frequently struggle to illuminate these processes at the individual level. We usually know whether a given artist or writer engaged with classical texts, or was inspired by antique art, and can often demonstrate how, particularly when we have evidence for which museums or libraries he visited, which books he owned and read, or how sound his grasp was of Greek or Latin. Yet the creative processes involved in ‘reception’ and ‘tradition’ remain mysterious.

These mysteries fascinate writers and artists, for whom they are more than merely a curiosity; but they should interest the rest of us as well, because without these processes we have no ‘classical tradition’ (and indeed no real culture at all).

Subjects Best Politely Avoided

Stendhal and his contemporaries lived through the French Revolution (1789–99), which is the earliest event in modern history that cannot be discussed without offending somebody, whatever your point of view. This makes discussions of his vision of ‘classicism’ surprisingly tricky.

Of course, historians are not alone among academics in being thin-skinned, neurotic and prone to hysterical rage when they find that someone disagrees with them, particularly in instances where they have no power or control over that person, or no means of seeking redress, or getting revenge, or otherwise punishing those not seen to ape or parrot what they themselves say.[3]

Perhaps the French Revolution is unique in having this effect even on those who are not professional scholars or teachers, particularly in France. The topic is worth avoiding, if you value peace, and prefer not to be yelled at by the emotionally damaged in their attempts to displace anger from other areas of their lives onto you.

Literature – particularly ancient literature – ought to be a safer topic. After all, if you cannot freely discuss books, poems, stories and works of fiction, chances are you cannot discuss anything else freely either.

Literary criticism may be thought of as the exercise of judgment on objects or subjects that may be trivial and frivolous in and of themselves. But the practice serves as ‘target practice’: it teaches you how to think and talk about things that really do matter. Stendhal understood this at seventeen, which is why he exercised such care in trying to teach his sister about literature. He was trying to help her form a sense of ‘taste’.

In the eyes of countless current scholars of literature, the concept of ‘taste’ is often treated as a mirage, or a harmful illusion, or a complex, intricate game of power, suppression and oppression, depending on how doctrinaire and paranoid they are, or how far they have become detached from what seems to normal people to be visible reality.

There are scholars who claim that standards of taste are merely arbitrary or illusory. Of course, we have all met individuals who claim a superior, hyper-refined taste sense of taste, judgement or aesthetics that does not withstand scrutiny, and cannot be justified logically. Without such people, there might be no fashion industry, or galleries of contemporary art.

In these cases, stated judgments of ‘taste’ generally amount to mere instruments of narcissistic manipulation, or passive aggression, whether or not they are consciously used thus. But the faculty of ‘taste’ is real, as Stendhal knew, and as every educated person with common sense seems to have realised until recent decades.

We may define ‘taste’ as “the ability to taste poison”. If so, then the crucial disputes over ‘taste’ should involve the questions: “how do we define ‘poison’?” and “what does it taste like?” When taste is examined from this angle, then the maxim de gustibus non est disputandum (usually translated as “in matters of taste, there can be no dispute” or “there is no accounting for taste”) seems, not merely cowardly, or philistine, but dangerously stupid.

Literature itself might not be terribly important most of the time, but discussions about the subject occasionally touch on matters of life and death.

What is ‘Classicism’?

In the passage from Racine and Shakespeare quoted above, Stendhal sneers about something that he refers to as ‘classicism’. Within French culture, the concept of ‘classicism’ is difficult to pin down, because (as noted earlier) it does not necessarily refer straightforwardly to Ancient Greek or Latin language, or ‘classical’ culture in the usual sense.

René Wellek (1903–95), who founded the Department of Comparative Literature at Yale University in 1947, helpfully elucidated the ways in which the concept of ‘classicism’ was seen in relation or opposition to ‘romanticism’, whose definition also slides around and metamorphoses depending on who is using it and why.[4]

Stendhal may be responsible for much of this: he adopted the terms ‘classicist’ and ‘romantic’ and developed them in opposition to one another, first in his letters, then his published criticism and pamphlets, and finally in his magnificent novels, from 1816 onwards. Of course, he is not merely a proud self-described ‘romantic’, but one of the most important writers of ‘the Romantic Era’, whose boundaries are as loose and elastic as those of ‘the Renaissance’ (another term that came into general use in the early 19th century). We might provisionally define it here as the period after the French Revolution that saw the rise and fall of Napoleon, and came to an end at some point in the 1830s.

‘Classicism’ has been a rather more fraught concept, certainly in a French context, in part because there has been nothing resembling a ‘classical period’ in recent centuries, even where predominant artistic fashions are concerned. During the late 19th century, the term ‘classicism’ gradually became unmoored from any necessary relationship to ancient texts or materials, until it degenerated into a shorthand for a reaction against perceived tendencies or excesses, not merely of the ‘Romantic’ movement, but the French Revolution itself.

Within 20th-century French history, this all became rather messy; the topic is best avoided here, since we value peace.[5] In the English-speaking world, a potentially Greekless, Latinless vision of ‘classicism’ is most closely associated with the Francophile Modernist poet-critics T.E. Hulme (1883–1917) and T.S. Eliot (1888–1965). Hulme died in the Great War; he is best-known today for his 1912 essay “Romanticism and Classicism”, which sets out a now-standard dialectic of ‘romanticism’ versus ‘classicism’:

Put shortly, these are the two views, then. One, that man is intrinsically good, spoilt by circumstance; and the other is that he is intrinsically limited, but disciplined by order and tradition to something fairly decent. To the one party man’s nature is like a well, to the other like a bucket. The view which regards man as a well, a reservoir full of possibilities, I call the romantic; the one which regards him as a very finite and fixed creature, I call the classical.[6]

Hulme introduced Eliot to this notion of a ‘classical’ point of view that is not really ‘classical’ at all in the usual sense of the term, but based on St Augustine’s formulation of Original Sin. Indeed, Hulme explicitly identifies ‘classicism’ as a fundamentally religious attitude. But Eliot muddies the waters further.

In “The idea of a literary review”, from the fourth issue of The New Criterion (January 1926), Eliot declines to define “the classicist tendency” strictly, or in straightforward terms; instead, he mentions six philosophical tracts, all of which are well-written in their way but none of which is obviously ‘classical’ in style, structure, rhetoric or tradition. Only one of them, the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain’s Réflexions sur l’intelligence (1924) was written by a man with recognisably religious, non-materialist views.

In theory, it is possible to believe in Man’s essentially sinful nature without believing in the Incarnation, the Resurrection, the immortality of the soul, or the Holy Trinity, or any notion whatsoever of God. Such a view is not necessarily incoherent or self-contradictory. Only it is very, very bleak, as the views of those whom Eliot described as exemplars of “the classicist tendency” undeniably were. You can guess that most of these ‘classicists’ held political views that are not now frequently discussed in polite society.

None of this had anything to do with what Stendhal was talking about, obviously. But ‘classicism’ is a dangerously slippery term, and we should try to keep it innocent of 20th-century politics, reserving it instead for an implied relationship with Graeco-Roman culture, and its perceived ideals. Stendhal used ‘classicism’ to refer disparagingly to a slavish, imitative relationship between an artist or writer and perceived ‘classics’, which are not always ancient, whether Greek or Roman. This still results in a mess; but at least this one can be cleaned up relatively painlessly, we hope.

What is a ‘Classic’ without ‘Classics’?

Stendhal was exasperated, not by ‘classical’ literature in the sense in which we now understand the concept, but by reactionary writers who sought to pretend that the Revolution had never taken place, and not only ignored the years 1770 to 1815 as much as they could, but tried to create literature in traditions that had already been obsolete, or even extinct, for half a century or more by the time the second edition of Racine and Shakespeare appeared in 1825. Also, he was living in a culture where you could discuss a 17th-century French ‘classic’ in the same breath as a Greek or Latin, genuinely ‘classical’ text. For this we may blame Voltaire.

Voltaire – François-Marie Arouet (1694–1778) – remains famous even though few of us read his work now; much of it seems glib, trite and hopelessly dated. But his 1751 historical treatise The Age of Louis XIV is still worth reading for its own sake. This book, more than any other, popularised the notion that King Louis XIV of France (1638–1715; reign 1643–1715, with a regency under his mother Anne of Austria until 1651) presided over one of four great ages in history, after the Classical eras of Athens and Rome, and the Italian Renaissance. Many Frenchmen continue to believe this to this day.

The finest literature produced during the ‘Grand Siècle’ (or ‘Great Century’), which effectively began with Louis XIII’s accession to the throne (1610), and ended with the death of Louis XIV in 1715, took on a genuinely ‘classic’ status in France from the mid-18th century onwards, even in instances where their authors barely knew any Latin, and ignored obviously ‘classical’ subjects. These works set the pattern for subsequent generations of authors, in form, structure, style, and approach to their material.

The first ‘classic’ of modern French prose, the Provincial Letters (1656/7) of Blaise Pascal (1623–62) is the work of a mathematical and philosophical genius who could certainly read Latin, but could not be described as erudite, brilliant though he was: this can be seen in the record of his 1655 conversation on Epictetus and Michel de Montaigne with Fr Louis-Isaac Lemaistre de Sacy (1613–84), who is best-remembered today as the author of an elegantly ‘classical’ French translation of the Bible (published 1667–96).

The Provincial Letters are a devastating satirical attack on the worldliness, hypocrisy and faulty theology of Jesuit priests; you will not find obvious references to anything Greek or Roman in this ‘classic’, only Neo-Latin theological texts, and passages from the Bible (which learned Catholics in those days generally read in Latin). But you can see virtues in the work that you might want to copy, from a literary, and especially a rhetorical point of view. A ‘classic’ in this sense is something you want to imitate. We do not really have ancient classical models that can teach us how to write effective anonymous attacks from within an absolutist, authoritarian society; this was not really a problem that the Attic orators (for example) had to worry about.

T.E. Hulme’s vague-seeming definition of ‘classicism’ applies remarkably well to the ‘classics’ of the Grand Siècle. Whilst the major playwrights and poets of the era were all genuinely erudite, the prose writers were as often as not educated principally at the ‘School of Life’, and had forgotten all their Latin by the time they began writing.

The philosopher and epigrammatist François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613–80) and the brilliant memoirist Louis de Rouvray, duc de Saint-Simon (1675–1755) often manifest a sort of ‘classicism’ in the clarity, balance and orderly restraint of their writing; but there is no direct or conscious influence from Julius Caesar, Seneca’s epistles, the histories of Tacitus or any other ancient writer in terms of the way they write prose; rather, these works are ‘classic’ in the sense that they became models for later French writers, including Voltaire himself.

In fact, Voltaire’s own shallow, reactionary artistic ‘classicism’ is a good example of the sort of writing that Stendhal scorned (or later claimed to scorn), where the imitation of conventional forms and language seems to have degraded to the level of a mere thoughtless ritual – this is particularly true of Voltaire’s tragedies, which appear to modern eyes to be nothing more than bad pastiches of great 17th-century dramas. But this is another discussion.

Another Type of ‘Classicism’

In Stendhal’s day, ‘classic’ French literature still referred mainly to works from the Grand Siècle that were imitated by lesser men. Today we might think of at least some of the works by Voltaire’s rival Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) as ‘classics’ in a vague sense (if only because they are published in the Penguin Classics and Oxford World’s Classics series of paperbacks). Stendhal would not have done so, despite the fact that he admired Rousseau and was influenced by much of his work.

Rousseau simply could not be a ‘classic’ author, in the stricter sense of the term: he was writing in a decadent century, not a great one; his novels, treatises and memoirs, whilst widely imitated insofar as they were exercises in a certain kind of self-expression, were written in a manner that resisted the very idea of a literary, stylistic or formal model. In this respect he helped originate a certain kind of ‘romanticism’.

All that said, Rousseau had a distinctly ‘classicist’ side to him, in a sense of the term that we Hellenists and Latinists clearly recognise, but would have been alien to Stendhal’s sensibility – or his use of the term ‘classicist’ anyway. This comes into focus in Rousseau’s 1758 treatise known as A Letter to M. d’Alembert on Spectacles. Rousseau was opposed to the establishment of a permanent theatre in Geneva, which was then a city-state with an ancient republican constitution. One of his forefathers had settled there as a refugee; he himself was a fifth-generation citizen of Geneva, and to the end of his life he remained proud of his hereditary voting rights.

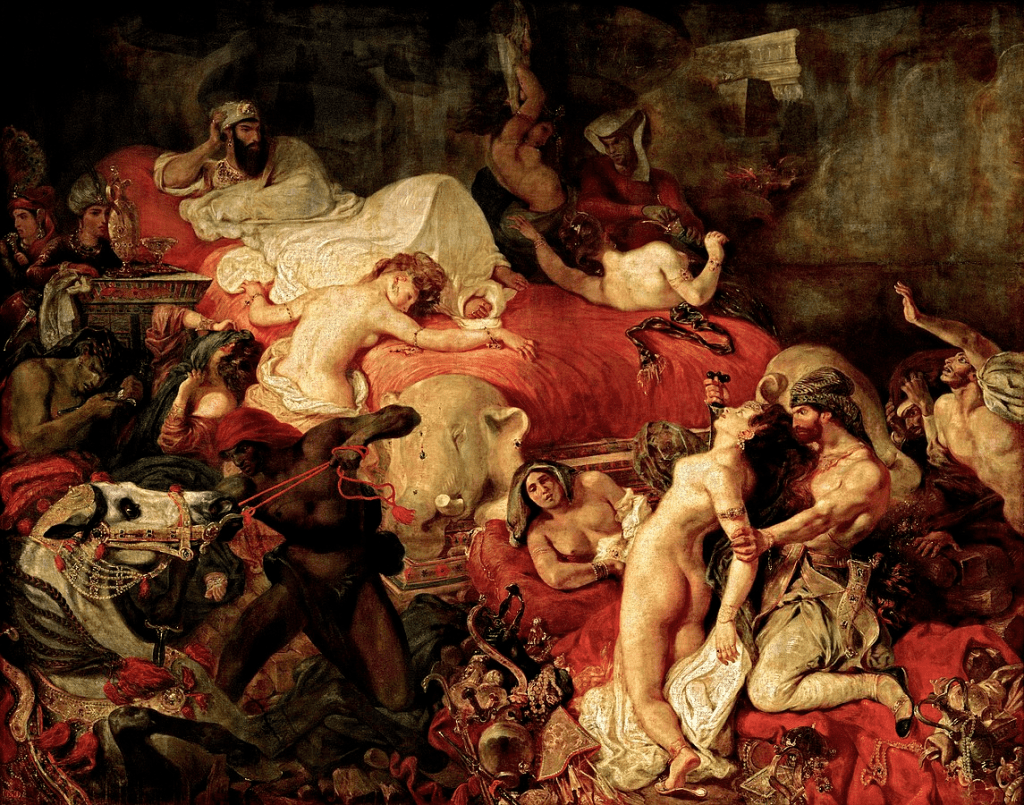

Rousseau’s unexpected censoriousness where live theatre was concerned was only partly intended to upset Voltaire, who loved the stage, and found himself bored in the evenings after he was compelled to move to Geneva in 1755. To Rousseau’s mind, a self-governing republic could not survive without strict enforcement of civic morality. Classical Athens was not his vision of an ideal state; Classical Sparta was.

Rousseau’s father had inculcated a deep sense of republican virtue in his son, who became preoccupied by the idea of Roman-style Republican austerity, of the sort that could be seen throughout the first ten books of Livy – even if Rousseau did not necessarily practise these virtues in private life. This vision was far more important to him than the one he encountered in Plato’s Republic, which parallels his ideas in the Letter to M. d’Alembert, but might not have inspired it. Rousseau’s father was more important than Plato in this respect.

Rousseau was not the only 18th-century philosophe to have fixated on an anti-decadent, anti-monarchist vision of Rome and what made the Romans formidable: the Baron de Montesquieu (Charles-Louis de Secondat, 1689–1755) had started these discussions with his 1734 study Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness and Decadence of the Romans. But Rousseau’s inflammatory political tract The Social Contract (1762), with its idealised picture of the Roman constitution as it existed for a few centuries after the kings were driven out in 509 BC, ended up enjoying a more focussed, direct influence than anything Montesquieu wrote, not merely on intellectual life, but on political events as well.

Fashionable Republicanism

Like all ambitious provincial bourgeois, Stendhal was sensitive to fashion. In the circles in which he wanted to move in Paris and Milan, Roman-style republicanism remained chic even after people in those circles lost privileges, rights, property, freedoms and (in a few instances) their heads. Stendhal’s commitment to the principles of the Revolution (as he conceived them) remained sincere throughout his life, largely because they created further distance between himself and his anti-Revolutionary father (who indeed sounds awful). Others were less firm in their convictions.

François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), whom Stendhal loathed mainly for political and philosophical reasons, but also for his prose style, exemplifies ‘received opinion’ among ‘enlightened’ members of the upper class at all stages of his life. As he records in his memoirs:

A man who landed in the United States as I did [in 1791], full of enthusiasm for the classical world, a settler looking everywhere for the regularity of early Roman life, was bound to be shocked at finding the luxuriousness of the carriages, the frivolity of the conversations, the inequality of wealth, the immorality of banks and gaming-houses, and the noises of dance-halls and theatres.[7]

The Livian, Rousseau-influenced fantasy of a ‘pure’ American Republic appears to have died hard:

When I arrived in Philadelphia, George Washington was not there. I was obliged to wait eight or so days to see him. One morning I saw him pass in a carriage drawn by a team of spirited horses, driven four-in-hand. Washington, according to my ideas at the time, had to be a sort of Cincinnatus; Cincinnatus in a chariot was a bit out of keeping with my notion of the Roman Republic, Year 296. Could Washington the Dictator be anything other than a rustic, prodding his oxen with a goad and steadily gripping the handle of his plough? But when I did go to him with my letter of introduction, I discovered the simplicity of an old Roman.

Chateaubriand wrote those words at a time when the popular notion of a ‘dictator’ still generally implied the preservation of a constitutional arrangement by temporary, extraordinary means, rather than anything more sinister or pejorative. Or if the word had unsavoury connotations in Chateaubriand’s mind, he would have been reluctant to give full voice to those thoughts. After all, whilst he criticised Napoleon severely (at one point comparing him to the Emperor Nero), and honourably suffered the consequences, he was still conscious throughout his life that he owed much of his prominence in public life to the ‘First Consul of the French Republic’ – that is to say, the military dictator of France, as Napoleon was before he crowned himself Emperor in 1804.

Part II of this essay can be read here.

Jaspreet Singh Boparai recently abandoned academia to cultivate the Muses. He has previously written for Antigone on Tacitus and the thrill of writing here, on the challenges of translating (pseudo-)Latin here, on the pleasures of Poussin here, on Neo-Latin syphilis here, on Apuleius the ‘witch’ here, on V.S. Naipaul and Latin here, and on the Classics and British India here.

Further Reading:

Whether or not you have French, you will want to read Benedetta Craveri’s wonderful 2001 study The Age of Conversation (published by New York Review Books editions in English in 2005) and inflict it on everyone around you. Craveri depicts the cultural background of the Grand Siècle and the 18th century better than any other modern writer.

You might also try to find as many books as you can by the late Marc Fumaroli (1932–2020), one of the most important men of letters of modern times. But his work does not translate well into English. See how you get on with Lara Vergnaud’s 2018 translation of some of his essays The Republic of Letters (published by Yale University Press in its ‘Margellos World Republic of Letters’ series).

Fumaroli would have no doubt told the beginner to skip his books and go straight to the originals, which are easy to find in cheap, scrupulously-edited paperback editions from Gallimard and Flammarion. If you can read French, you have no excuse not to; if you are rusty, there are still some texts of Molière and La Fontaine in dual-language editions (with English on facing pages, as in the Loeb Classical Library) from Dover Publications. There is also an edition of Pascal’s Provincial Letters.

Those who need the English menu in tourist-trap restaurants in Paris (sometimes we all do) will get a flavour of what they are missing from the astonishingly good translations of Molière by the American poet Richard Wilbur (1921–2017); these have been collected in two volumes by the Library of America (2022).

Notes

| ⇧1 | This and the subsequent translation are by Norman Cameron, To The Happy Few: Selected Letters of Stendhal (Grove Press, New York, 1952). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Quotations from Racine and Shakespeare are taken from the translation by Guy Daniels (Calder Publications, London, 1962). |

| ⇧3 | To be fair, we should admit that most of these people are far too cowardly for active aggression, and prefer to exercise the passive type, which allows them to indulge in longer-simmering fantasies of vengeance. |

| ⇧4 | See three of Wellek’s essays in particular: “The concept of ‘Romanticism’ in literary history I: The term ‘Romantic’ and its derivatives,” Comparative Literature 1.1 (Winter 1949) 1–23; “The concept of ‘Romanticism’ in literary history II: the unity of European ‘Romanticism’”, Comparative Literature 1.2 (Spring 1949) 147–72; “French ‘Classical’ criticism in the twentieth century,” Yale French Studies 38 (1967) 47–71. |

| ⇧5 | René Wellek’s 1967 essay in Yale French Studies, “French ‘Classical’ criticism in the twentieth century,” sketches some of the artistic background to this; but there is no way of going deeper into this topic without examining areas of 20th-century history that occasionally turn ugly. The single best introduction to the circumstances that gave rise to this ‘classicism without Classics’ remains Eugen Weber’s Action Française: Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France (Stanford UP, Redwood City, CA, 1962). Weber’s book is a must-read; be warned that it is much easier to find in French translation than in the original English. Stanford University Press, or some other enterprising publisher, ought to reprint it, not least because it helps shed light on certain contemporary circumstances that have arisen again after having lain dormant for decades. |

| ⇧6 | The full text of Hulme’s essay may be found here, courtesy of the Poetry Foundation. |

| ⇧7 | From the New York Review Books Classics edition (2018) of Chateaubriand’s Memoirs from Beyond the Grave 1768-1800, translated by Alex Andriesse; Book 6, Chapter 7. All excerpts from Chateaubriand in these essays will be taken from this version – which deserves applause. |