James Willis

James (“Jim”) Alfred Willis (1925–2014) was an accomplished Latinist who dedicated almost all of his life to philological questions. After studying at Brentwood School in Essex, and University College London, Willis became a Lecturer at UCL in 1949. In 1962, he moved to the other side of the planet to become a Reader at the University of Western Australia; here he spent the next half century of his life. Appointed Professor of Classics and Ancient History in 1973, he continued a productive scholarly life both after and before his retirement in 1988.

Willis’ work was primarily as a textual critic; such a focus encouraged clarity and specificity in lieu of generalisation and abstraction. For a man of unusually strong convictions this was not a problem. He produced editions of Macrobius’ Saturnalia and commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis (2 vols, Teubner, Leipzig, 1963), of Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii (Teubner, Leipzig, 1983), and of Juvenal’s Satires (Teubner, Stuttgart, 1997), each of which rewards careful reading. His Latin Textual Criticism (Univ. of Illinois Press, Chicago, IL, 1972) sought to set out and elucidate the art of textual criticism – to the degree to which an art, not a science, can be so reduced and taught. All of these works provoked spirited criticism, sometimes fairly.

The following lecture was first delivered in April 1991 at the 6th biennial International Interdisciplinary Conference of the Society for Textual Scholarship held in New York. The typescript was sent to one of the Antigone editors before the author’s death. The lecture was later reprinted in the journal Text (vol. 6, 1994, 63–80); we are very grateful to Professor John Young, editor of Textual Studies (the sucessor of Text) for permission to reproduce the original text for a public audience. Willis combines his particular brand of humour with a refreshing awareness that all do not see the world, whether it is textual criticism or matters of wider import, quite the same way as he does. We regret that we have found neither obituary nor likeness of Willis to share with curious readers.

The Science of Blunders: Confessions of a Textual Critic

Some apology is sure to be demanded for a life largely devoted to what has been often called “mere verbal criticism” and regarded as no more than fiddling with letters and words which are of no importance in the wider horizon of the historian or the literary critic. Now while it would be useless to attempt to apologize for the lack of success with which I personally have practised the trade of a critic, for the trade itself much may be said in its defence. That textual criticism is a waste of time will be always believed by those who accept the texts of Greek and Latin authors as coming from heaven above by permission of the Syndics of the Oxford University Press, and therefore I will preach only to the convertible – to those who are willing to ask the simple question, “How do we have any knowledge of the Greek and Roman world?”

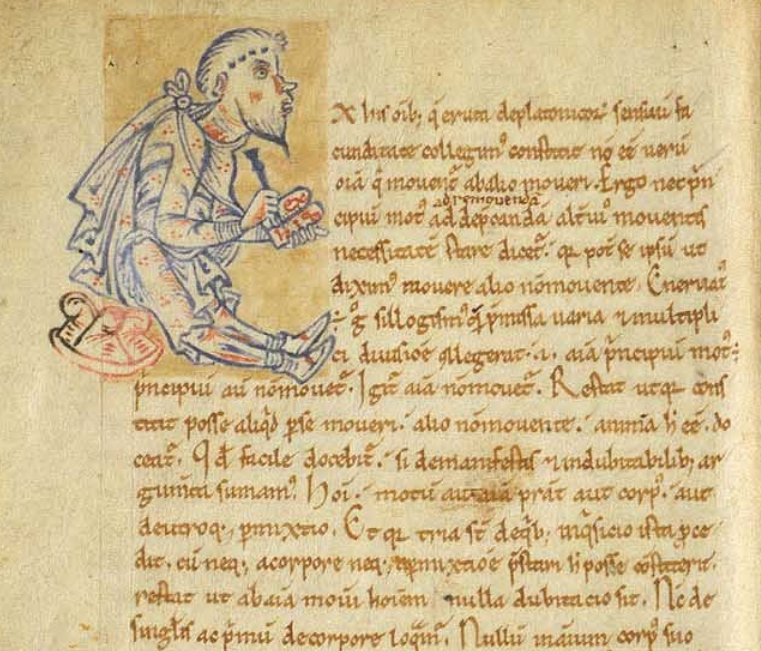

We know of the Greeks and Romans through concrete objects and through the witness of words. Temples, bridges, houses, statues, and the like have physically survived the centuries, and from them we can learn much; inscriptions on durable material have survived, and the diligent collecting and examining of these have made immeasurable additions to our knowledge: yet if we want to know what Greeks and Romans thought and said about the world and about each other, we depend overwhelmingly on written materials – “the literary sources”, as professional historians call them often with a somewhat deprecating tone. Here we are not dealing with physical survivals. Sophocles and Plato and Cicero and Virgil did not carve their works in imperishable bronze or stone; they wrote them, or caused them to be written, on highly perishable papyrus. Before that substance crumbled, the text would be copied (or so the author hoped) onto new papyrus; when that in turn crumbled, onto new, and so forth: the material passed away, but the text lived on, so that nothing of the original thought and language was lost.

Oh that it were so indeed! But the real world is not like that. At every copying there is the possibility of human error. I say “the possibility”, but it is nearer to certainty. Copying is usually a boring task; boredom breeds inattention; inattention breeds mistakes. Therefore the manuscripts of classical authors contain mistakes. The detection and correction of mistakes in texts is the function of textual criticism. Therefore textual criticism is necessary, Q.E.D.

But, you will say, with that instinctive distrust of deductive reasoning which is the salvation of the English-speaking world, that is a mere train of thought. “Where are they, these supposedly inevitable errors? We read Caesar at school, and the text seemed alright.” Yes: a school text seems pretty good, but precisely because textual critics have worked upon it. Consult anything that claims to be a scholarly edition, and you will find at the bottom of the page an apparatus criticus, which most people, including some dictionary-makers, prefer to disregard. That apparatus is essentially a record of the mistakes which various copyists have made in various manuscripts, and in some difficult texts the critical apparatus can fill half of the page. Now if there are several rival readings, only one can be right. They may be all wrong, and then we can recover what the author wrote only by conjectural emendation, which is a polysyllabic way of saying by guess or by God. Now to tell which, if any, of a number of. variant readings is the original, we have to assess two kinds of probability. One is commonly called intrinsic probability: we ask, “How likely is it that Virgil or Ovid or Juvenal wrote these words? Are they Latin? Are they sense?” The other has been named transcriptional probability; we ask, “How likely is it that this reading should have arisen from that by a mistake in copying?”

Now some mistakes in copying betray themselves at once by giving a ludicrously inappropriate sense. The Times of Allahabad once wrote of India as “the cradle of civilization and nursery of rats”; the Manchester Guardian, which was at one time noted for the quaintness of its misprints, had to correct a line of poetry in which the words “and would his duty shirk” had been misprinted as “and mould his dirty shirt”; I observed recently in reading a trivial science-fiction story that, while the author had wanted to speak of that well-known astronomical object the Crab Nebula, the monotype operator had unfortunately confused the letters b and p. We have all heard of such absurd blunders, the most hackneyed involving the confusion of battle and bottle, winch and wench, live and love, and so forth.

Unfortunately not all copying-mistakes are ludicrous, and (which is more troublesome) not all are obvious to the general reader. There is a scene in the novel Jane Eyre in which the housekeeper Mrs Fairfax takes the heroine up to the roof of Thornfield Hall to show her the view over the park and surrounding countryside. As they descend, Jane goes first, while Mrs Fairfax stays to secure the trapdoor. A moment later Jane hears Mrs Fairfax’s step on the “great stair”. The immediate context, together with the general topography of Thornfield Hall as given in the book, makes it impossible that Miss Brontë should have written “the great stair”. It was the garret stair that was supporting the respectable weight of Mrs Fairfax, yet “great stair” appears in every edition. Likewise, in one of the quoted fragments of Menander’s Dyscolus, one of the personages addresses another as daer “brother-in law”. No one looked on this reading with suspicion, particularly (I suppose) since a play of Terence’s, based on a Greek New Comedy original, is called Hecyra or The Mother-in Law. But when the full text of the Dyscolos was recovered, the Terentian title proved to have given us what is vulgarly called a bum steer, for one of the personages in Menander’s play is a slave called Daos, and it is he who is being addressed in the vocative case Dae.

Here there might have been some reason to question the reading, for daer is a remarkably old-fashioned and poetic word to find in the colloquial language of New Comedy. In other instances there is nothing at all to raise suspicion. In Shelley’s Stanzas Written in Dejection near Naples we find in some editions the words, “the breath of the moist air is light,” but in the better texts which follow the first edition we find, “The breath of the moist earth is light.” The latter is better certainly, but who would have dreamed of suspecting air if we had no other witness to the text? Again, in a fragment of Archilochus, long known from its being cited by Macrobius, the poet calls upon Apollo to point out (semaine) the guilty; a papyrus fragment now has instead pemaine, “afflict”, which seems to me better and worthier of the vindictive Archilochus. There could have been, however, no reason whatever to suspect semaine of being a false reading.

Here are two important points. First, there is no such thing as certainty in textual criticism. A word or phrase may be quite unobjectionable; it may give excellent sense and perfect grammar, but it may be wrong for all that. You will hear from time to time a classical scholar gravely declaring that a conjectural emendation may be ingenious and attractive, but that it can never be certain. True, but the same holds good of the transmitted text. Of a very few Latin authors we have manuscripts which go back to classical antiquity, which even so is much as if our best authority for the text of Shakespeare were a hand-written copy dating from the 1930s. With reasonable luck we may have manuscripts going back to the 10th or 9th century, which by careful comparison one with another will let us reconstruct the readings of a single manuscript which survived the chaos of the 7th and 8th centuries to reach the Carolingian age. Of many authors the textual fortunes have been much worse. For the poems of Catullus we can go no further back than a manuscript which existed at Verona in the 14th century, but which exists no longer. For the historical work of Velleius Paterculus we have no better authority than the earliest printed edition. If certainty is what we are looking for, the texts of classical authors are an ill-chosen hunting-ground.

The second point is equally to be borne in mind. If the witnesses to our text do not agree among themselves, it is not enough to choose a reading which is satisfactory in itself: we must choose that reading which best explains how the others could have arisen through faulty copying. Thus we may note the pemaino is a fairly rare verb, virtually confined to poetry (Liddell and Scott give about 30 occurrences), while semaino is common in all periods and types of literature (L. & S. give some 140 occurrences); consequently pemaino is more likely to have been corrupted into semaino than vice versa. The problem may be made clearer by an example fabricated for the purpose in English. Let us suppose that someone has written a melodramatic story of love and virtue triumphant while lust and villainy are discomfited, and that the vile Sir Jasper is riding as fast as he can in pursuit of his fair prey:

Sir Jasper lashed his horse furiously,

says one manuscript copy;

Sir Jasper lashed his beast furiously,

says another, while a third has

Sir Jasper lashed his breast furiously.

Which is the true reading? There is nothing wrong with horse in itself, but if the author wrote horse, how came it to be corrupted into beast, and breast? Breast of course is nonsense. Now if the author wrote beast, a dreaming copyist might have written breast, especially if he was thinking of the wedding guest who beat his breast when he heard the loud bassoon. An intelligent scribe, confronted with the absurd reading breast, might see that Sir Jasper must be whipping his horse and mend the text accordingly.

A rather similar problem, except that the true reading needs to be supplied conjecturally, is found in Northanger Abbey, Chap. 26: “By ten o’clock, the chaise-and-four conveyed the two from the Abbey…”. Who were the two occupants of the chaise? They were General Tilney, his daughter Eleanor, and the heroine of the romance, Miss Catherine Morland. Therefore Miss Austen could not have written the two. What did she write? In a copy possessed by her sister Cassandra the word two has been corrected to three, but there are not many people who would misread three as two. There can be little doubt that we must read conveyed the trio from the Abbey, as several critics have proposed independently. To ask whether Miss Austen elsewhere speaks of a group of three people as a trio is a legitimate question. She does indeed: Mansfield Park, Chap. 11: “They were now a miserable trio…”.

Such situations as this occur very often in texts of the Greek and Latin classics, and it is the duty of any responsible editor to regard as the most authentic reading the one which best explains the genesis of the others. Hence arises the dictum “Difficilior lectio potior” – “The more difficult reading is to be preferred.” With the truth of this principle no one can disagree, provided that we remember that by “difficult” we mean “difficult to the copyist”, not “difficult to the modern scholar”. As a general rule, the men who copied manuscripts in the Latin middle ages knew a little Latin, but not much, and this is perhaps the state of affairs most productive of mistakes. If we know nothing of a language, we copy the text letter by letter, and our mistakes are confined to letters. If we understand a language perfectly, our grasp of its meaning helps us to do our job of copying, because we will not write anything that is senseless. But if we are perched on the isthmus of a middle state, we will tend to replace unusual words and constructions by others that we know better, turning correption into corruption or correction, contusion into confusion, ingenuous into ingenious and so forth.

In the 18th century the common way of producing a new edition of a classic was to reprint the text of the most esteemed previous edition, making changes only where something seemed to be wrong with the reading accepted by one’s predecessor. The next step was to look in any manuscripts that came to hand until one of them yielded a reading that gave a tolerable sense. This reading would then be adopted into the text, the editor proudly claiming that he had restored the true reading from an excellent manuscript reposing in the library of that munificent patron of the arts, the Palsgrave of Pumpernickel, to whose mightiness he dedicated his humble work. In other places neither the editor nor his readers had any idea on what manuscript authority the text was based.

If this is the wrong way to use manuscripts, what is the right way? When the gods have so driven a man out of his wits that he decides to produce a critical edition of a classical Latin author, what does he do? Obviously he must find out what the manuscripts of that author are. For the modern scholar this is usually a straightforward task. Several standard works will tell him what the most important manuscripts are; after that he betakes himself to the published catalogues of manuscript collections. There may be in these some errors and omissions, for the cataloguing of manuscripts is slow work and badly paid work, and it is not easy to find men and women to do it well. Yet we owe a great debt of gratitude to those obscure researchers, for without their guidance we should be wandering in darkness. Within a few months we should know of all the manuscripts which contain our author’s work. Now we have to examine them all and record all their variant readings.

Here a difficulty can arise. When I began work on the text of Martianus Capella, I soon learned that there were nearly 250 manuscripts of this author, whose text ran to a little over 530 pages in the previous printed edition. A few calculations of the time needed to report the variant readings of a single page, with the assumption that I should work on it for three hours every day, excluding Saturdays and Sundays, revealed that the task would take me roughly thirty years, after which I should still have to select the readings which seemed to me best, reduce my collations to the form of a critical apparatus, type the whole thing out together with prolegomena and index, and correct the proofs. Since I was already 38 years old, I had obviously started too late. I felt like the old lag who, when sentenced to fifteen years’ penal servitude, cried out, “But, My Lord, I shall never live to finish such a sentence.” The judge, you will remember, kindly replied, “Never mind: just serve as much of it as you can.” But in sober truth this is a difficult problem. If there is not time to examine all the manuscripts, which of them do we exclude? It would seem reasonable to omit the later manuscripts and take a stand on the early ones; yet there may be a 15th-century manuscript copied directly and carefully from one of the 9th century, which is no longer extant. I am ashamed of the advice which I should give to a young scholar in such a case, for I should say, “If you have ten or a dozen from the 9th and 10th centuries, stick to those and neglect the others. As for the hypothetical manuscript of late date which is a copy of a lost manuscript better than any which survive, forget it. Probably there isn’t such a manuscript; if there is, maybe no one will find it, and if someone does find it and makes a great fuss about it, with a little bit of luck you’ll be able to argue that all its good readings are conjectural.” Strict scientific method could be followed only if one had a team of devoted students who would each examine a few manuscripts and hope to get Ph.D.s or published articles out of it as their cut. In the heyday of the German universities this farming-out of learned labour was a regular part of the system.

Well, setting this problem aside, let us suppose that the collation of manuscripts is completed. We have now all the readings of all the manuscripts. What do we do with them? We examine them in the hope of doing two things: first of working out in individual passages by what historical process the different readings in different manuscripts arose; secondly of establishing in consequence what relationships there are between the various manuscripts – whether manuscript B is a copy of manuscript A, or whether A and B are copies of an original which is not one of those known to us and therefore presumably is no longer extant. The first of these inquiries involves what I have called the science of blunders – the name sphalmatology, jokingly invented by the late J.B.S. Haldane, has not achieved circulation, but the study deserves to be an -ology in its own right, and to endow a readership in it would be less waste of money than many things which I have seen done in the academic world.

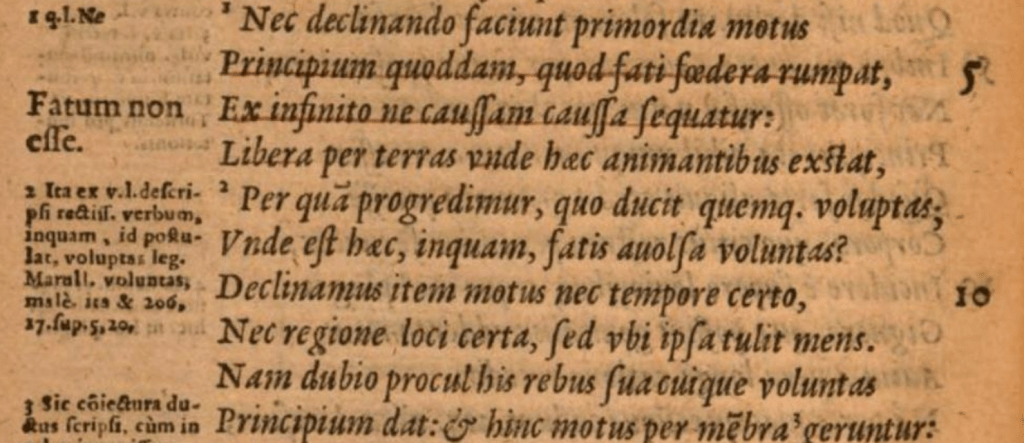

Of course to the average classical scholar, who is no more exempt than the rest of mankind from a distaste for thought, the whole thing is very simple. Mistakes of one letter occur from time to time; mistakes of two letters are rare; mistakes of three or more letters hardly ever happen. This view arises from a wrong approach – from that approach which tries to find out things about the real world by thinking about them without observing them. If I wanted to know what are the most common causes of breakdowns in motorcars, I should not try to work it out by deductive inference from first principles: I should instead write to the R.A.C. and ask whether they kept records of all the occasions on which their breakdown service was summoned and of the cause of the breakdown on each occasion: if they did, and if they were willing to impart that information to me, I should be in a fair way to gain the knowledge I wanted by inductive reasoning from observed phaenomena, which I take to be the only way of finding out what happens in the real world. We can know what mistakes are likely, therefore, only by seeing and noting what mistakes are actually made. Most copyists do not copy letter by letter; their unit of recognition is the word or small group of words. A single proof of this fact will suffice. No two words are more often confused in Latin manuscripts that voluntas “will” and voluptas “pleasure”. This can hardly represent a confusion between n and p, for the two letters are quite unlike each other. On the other hand, in most manuscripts of the middle ages an n can look very like u, and c can look very much like a t; yet we never find noluntas or voluncas as misreadings of voluntas because these are not Latin words.

We may reinforce this lesson as to confusion of single letters by considering the trouble sometimes given by the old-fashioned long s (ſ), which lingered in English printing until the end of the 18th century. The form of the letter may mislead us into thinking that we see fight or fought or flew when in truth we have sight or sought or slew, but we never think that we see fparrow or fpinfter or faufage, because those are not English words. In a man who writes a book about the 18th century one does not expect to find such confusions, but here is a quotation from a poem of Bath and its waters as it appears in John Walters’ book on Beau Nash:

Here beauteous females in conception flow,

By genial waters soon more fertile grow.

Here barren ladies may their wants relieve,

But by the waters only they conceive.

Here balls and plays and all diversions reign,

No pleasures fully, and no freedoms stain.

Only a moderate degree of attention was needed in order to see that the rhymester wrote slow in the first line and sully in the sixth. Soon in the second line escaped corruption because there is no English word foon.

I am not saying, of course, that difficult hands with badly formed letters do not make mistakes more likely: they certainly do. That busy publicist Horace Greeley wrote one of the worst hands ever known. An American typesetter once said of it that if Belshazzar had seen that writing on the wall, he would have been a heap more frightened than he was. In one article Greeley quoted Polonius’ words, “‘’Tis true ’tis pity, and pity ’tis, ’tis true.” The baffled compositor produced the following strange arithmetic: “’Tis two, ’tis fifty, and fifty ’tis, ’tis five.” Another famous Yankee, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, had a scarcely less atrocious hand; it was said that only his daughter could read it, and that she worked on three fundamental principles – that if a letter was dotted, it was not an i, if it was crossed, it was not a t, while if a word was spelt with a capital letter, it did not begin a sentence. Yet even the realm of typesetting is subject to Murphy’s Law. Edward Lane, the Victorian translator of the Arabian Nights, wrote a clear and elegant copper-plate hand, and yet he found his proofs abounding with errors. When he sought an explanation, the printer told him that his writing was so good that the setting of it was entrusted to apprentices: the time of an experienced man would be wasted on such easy work. For many decades now, of course, printing-houses have demanded that all copy be typewritten: whether this practice has made printing more accurate I cannot say.

The most common kind of mistake then is the replacement of a word by another of similar shape, usually a more common word. The horse-hoe recommended by Jethro Tull becomes a horse-shoe; the fossil plants called calamites become calamities; immortality becomes immorality, and so forth. F.W. Hall in his Companion to Classical Texts cites two beautiful examples from the Times newspaper: “One doctor described his case as that of miniature development” (for immature); and, “The Crown makes no claim to lumbago found in lands sold by it prior to 1901” (the mineral plumbago being intended). An edition of the Bible printed in 1717 by the Clarendon Press gave the heading to Luke Chap. 20 as “Parable of the Vinegar” (for vineyard). Sometimes the mistake seems to have arisen from a mis-hearing of dictation, as when the Daily Telegraph at some time in the 1950s assured the British people in regard to one of their recurrent financial crises that “We have shot the rabbits and are now in clear water again.”

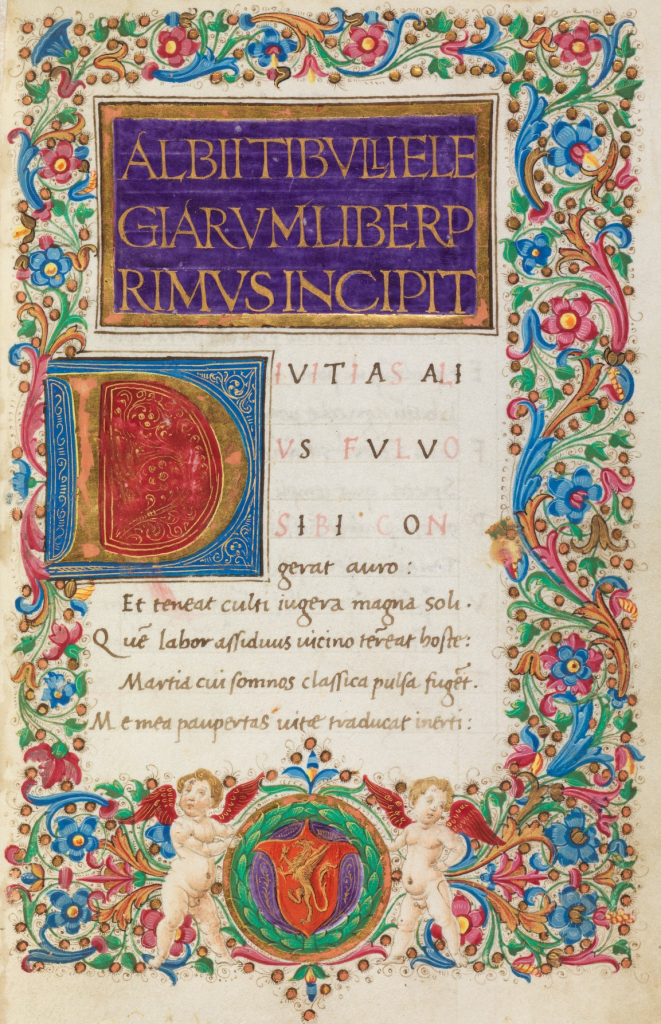

This last error [rabbits for rapids] leads us to another curious cause of copying-mistakes, which could be called preoccupation. The notion of shooting, no doubt, brought rabbits and such small deer into the compositor’s mind. Similarly a familiarity with the routine of the printing-house may have produced the famous blunder, “Printers have persecuted me without a cause,” and Freudian psychologists will have no difficulty in explaining why the printer of the Bible in 1621 omitted the word not in the seventh commandment. A striking example of this kind occurs in the text of Horace (Odes 3.18.12): the poet describes a country village on holiday, and says that the community on holiday lies in the fields together with the oxen who also are at ease – festus in pratis iacet otioso cum bove pagus. A copyist who must have been familiar with Isaiah 11.6, “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid,” has written pardus “leopard” for pagus “village”. In the passage where Tibullus says to his girlfriend, “I should love to live with you” (tecum vivere amem), some dreaming monk has written tecum vivere amen.

The substitution of words not of the same shape but of the same meaning is less frequent, but more troublesome. This fault is the fault of memory rather than of vision, and it occurs often in quotations made from memory. Thus Milton’s “Tomorrow to fresh woods and pastures new” is often misquoted as “Tomorrow to fresh fields and pastures new”; we often hear that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, but Pope wrote “a little learning”; Quintilian quotes the second line of Virgil’s first Eclogue from memory and gives us a rustic muse (agrestem Musam) where the manuscripts of Virgil have a woodland Muse (silvestrem Musam). In Latin manuscripts the substitution of a synonym, where it occurs, more often than not arises from the misunderstanding of an explanatory note. Tepor, for example, means warmth, and so does calor, but the latter is a much more commonplace word, as is shown by its survival in the romance languages (Sp. calor,Fr.chaleur);hence someone who thinks that other readers may stand in need of his expert guidance (a type of human personality that is always with us) writes calor between the lines or in the margin to tell lesser mortals that that is what tepor means. The next numbskull to copy out the text supposes that calor is a correction and writes it in place of tepor. Or of course he may suppose that the marginal reading is something that has been left out and ought to be restored, and so he writes tepor calor.

There is of course one area in which the mistaking of individual written characters is the predominant type of error – that is in the copying of numerals. To mistake one numeral for another – a 1 for a 7, a 3 for a 5, etc. – is too common to need remark. Some interest attaches, however, to the mistaking of figures for letters or vice versa. A printer once described an old country house as having “219-209 passages”, where the author had written zig-zag. The title of a book on F. Scott Fitzgerald appeared in a bookseller’s catalogue as “Scott Fitzgerald – Chronicler of the 1933 Age” (for Jazz Age), and that great navigator James Cook was oddly transformed by a French typesetter into “M. le capitaine 600 kilometres.” Several years ago, when numerical postcodes were a new thing, my friend, Dr Melville Jones, received a letter addressed to him in Dalkeith, Waboog [for WA 6009].

More troublesome than substitution is omission. Few things are easier in copying than to leave out several words because the same word occurs twice, especially if it should occur the second time immediately under the place where it occured first. In looking through the typescript of this paper I found that I had typed “from time”, where I meant “from time to time”. A striking example in Greek comes from Euripides’ Helen. Menelaus meets that heroine in Egypt, and asks her (since he does not recognize her at once),

Ἑλληνὶς εἶ τις, ἢ ‘πιχώρια γυνή;

Greek art thou, or a native of this land?

She replies

Ἑλληνίς· ἀλλὰ καὶ τὸ σοῦ μαθεῖν θέλω.

Greek; and thy nation too I fain would know.

In the text of Euripides, through the repetition of the first word, the verse has entirely vanished. By a remarkable stroke of luck Aristophanes puts the verses into the mouths of Euripides and the disguised Mnesilochus in the Thesmophoriazusae, and so the loss can be repaired. For the most part, however, what is lost is lost, and nothing but the discovery of new manuscripts independent of those which we have (a prospect most unlikely in the case of Latin authors) holds out any hope of restoration.

Loss can of course be occasioned by purely mechanical misfortunes. No bookbinding lasts for ever: the stitching goes, and leaves can fall out, sometimes to be lost, sometimes to be replaced in the wrong order. Sometimes a single leaf that has become detached is the only part to survive. In 1772 a single leaf was found from the 91st book of Livy in the Vatican Library; what happened to the rest is anybody’s guess. When Aldus Manutius was editing the letters of the younger Pliny, he used a manuscript of the early 6th century from a monastery near Paris. What happened to it after he had used it we do not know; the monastery certainly never got it back. Shortly before the First World War, however, Pierpont Morgan bought six leaves of an ancient manuscript which had been owned by some Neapolitan nobleman: they are part of that missing manuscript, but no-one knows when they became detached or where the rest of it is, if it still exists.

Thus far we have considered mostly mistakes which arise at a single blow. It is, of course, possible that an error committed by one scribe may engender a second error by another, and that in turn a third, and so forth. From that rich storehouse of blunders and lies, the transmission of Martianus Capella, I draw an example. Taking his material from Pliny the Elder, Martianus writes that the province of Hispania Baetica has four seats of the administration of justice, and he gives their names. Unfortunately there are only two names in his list; two have been lost through similarity of ending Cordubensem… Hispalensem. The manuscripts of Pliny have all the four names, and thus we can see that the omission of two was a blunder made by a copyist – not by Martianus Capella himself, for he would not then have put the numeral quattuor. Now of the manuscripts of Martianus Capella a few faithfully retain the original mistake; the rest have either altered quattuor to duo or left out the number altogether. There is a remarkable corruption in the same author’s book on geometry, where it can be shown that the reading printed in the Teubner edition of 1925 was the last of five stages of corruption, the first having been the omission of ten or eleven words caused by the similarity of ending of two Greek words.

Now here I think that textual critics have to keep their imagination under control. The five-stage corruption which I have just mentioned is attested in the manuscripts – the simple omission which began it, the various attempts of copyists to fill the gap, and the conjectures of editors who did not realize that the manuscripts which they were using were falsified. But beware the flashing eyes and floating hair of him who postulates such a chain of successive corruptions when none of the intermediate stages is attested, who tells you that skull was corrupted to skill, then skill to still, still to stall, stall to stalk, stalk to stack and so forth. With enough ingenuity one can devise a number of stages through which almost anything could be corrupted into anything else, but these schemes bear as much relation to real events in copying as the designs of Heath Robinson bear to real engineering.

With any luck, by the time we have analysed the mutual relations of the variant readings, we should be able to work out the mutual relations of the manuscripts. Then, if we can show that manuscript Q was directly copied from manuscript P, we can forget about Q, for it has no independent authority. Now we can argue that Q is copied from P if it has every one of P’s mistakes plus some of its own. There is one abatement of the severity of this condition: If Q has a few readings right where P has them wrong, it may be that the man who wrote Q was a clever guesser. Now the idea of being able to discard some of the manuscripts as being mere copies of others is very attractive, and editors have often been seduced by its charms so far as to discard manuscripts which could not possibly be mere copies of certain known others. Struck by a few agreements in error, they have overlooked true readings which could not plausibly he assigned to conjecture. One editor of Euripides went so far as to discard one manuscript as being a copy of another when the supposed copy contained two plays which were not in the supposed original. My own experience leads me to suspect that direct copies of extant manuscripts are rather rare birds, because so many manuscripts which formerly existed now exist no longer. If we had now every manuscript that there ever had been of the classical text in which we were interested, it would be possible to work out exactly how they were related each to each; with at least three quarters of them missing, the task is enormously difficult, but it would still be theoretically possible except for one thing which I have not mentioned: the variant readings of one manuscript often find their way into a manuscript that is not related to it by direct copying.

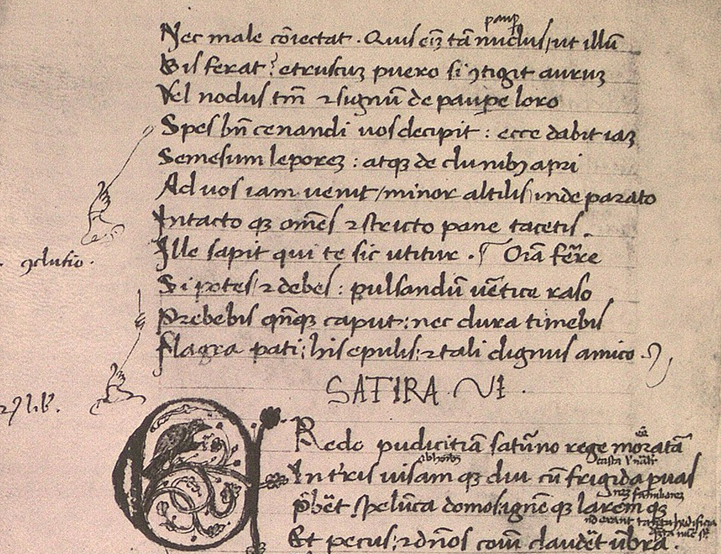

There were textual critics in the middle ages too (it is a curse from which no period of history has been wholly exempt), and they would sometimes try to improve the text of their own manuscript of Juvenal, for example, by consulting another manuscript and noting its variants in the margin. When the manuscript thus supplied with variants was next copied out, the copyist would adopt some or all of the variants, and the manuscript thus produced would give a text which is mixed and comes effectively from two sources, not one. For this reason it is not very often possible to say, “This manuscript is a copy of that,” while on the other hand we can often say, “This manuscript is more recent than that and has many of its characteristic errors.” The family-trees of manuscripts which you will often find in the prolegomena to critical editions are not comparable with the family-trees of noble families: they deal with general resemblances rather than with precise questions of fatherhood and motherhood. Again we are in a position where, with the sensible Mrs Dashwood, we may say, “Are no probabilities to be accepted, merely because they are not certainties?”

Let us suppose then that our editor has surveyed the manuscript evidence, classified the manuscripts, and decided what readings, on the basis of that manuscript evidence, are best attested, is he ready to sit down at his typewriter or his word-processor and start typing up the copy for the printer? No, he is not; there is other evidence that he has not yet examined. Simply by examining the manuscripts of Euripides, however well you did that job, you would not be able to restore that missing line in the Helen, of which we spoke earlier. Sometimes earlier writers are quoted or imitated or parodied by later writers, and if those sources survive, they may cast light on passages imperfectly transmitted in our manuscripts. We have seen how the text of a source, Pliny the Elder, revealed to us exactly what had gone wrong in the text of Martianus Capella, and indeed in that author, since most of the sources are extant and since the manuscripts of Martianus himself are very corrupt, the careful comparison of the sources and the borrowings pays considerable dividends.

Here I may make one of those confessions promised by my subtitle. In 1968 I produced what was meant to be a critical edition of Macrobius. I will refresh your memories: hewas an authorof the 5th century and a rank plagiarist by modern standards. He throws around the names of old republican Roman writers and of little-known Greek writers, but we have good reason to believe that they are all at second hand, for in many cases the books from which he took his material survive, and we see that he suppressed the name of the immediate source, leading us to believe that he had personally read those writers whom he parades before us. Thus much of his material comes from the 2nd-century Aulus Gellius: roughly speaking, all Macrobius’ knowledge of Roman republican literature is borrowed from Gellius. Hence the editor of Gellius cannot neglect the evidence of Macrobius, and Mr Peter Marshall made exemplary use of that evidence in producing his Oxford Classical Text of Gellius. The editor of Macrobius, on the other hand, rushed into print without carefully examining the evidence of Gellius, and not only did he receive unfavorable reviews – that does not matter – but he left the text unimproved where it could have been made better. For example, Macrobius speaks of the notorious Egyptian king Busiris, who was accustomed, he says, to sacrifice on his altars men of all nations – homines omnium gentium. Now the corresponding passage of Gellius has hospites omnium gentium, “foreigners of all nations.” This is obviously the true reading: Busiris did not sacrifice his fellow Egyptians, he sacrificed only foreigners who came to Egypt from outside. This is evidence of a kind which no editor can afford to disregard if he wants to do his job in a workmanlike manner.

So much then for the way in which the textual critic approaches and performs his task. If he does it well, what does he gain thereby? For himself, very little beyond the satisfaction of a job well done. He will not receive rave reviews, because those who are not textual critics cannot judge his work, and those who are include among their ranks some of the most quarrelsome of mankind. Further, the critic becomes (unless he is of most unusual character) emotionally involved with his work. The pangs of a lover whose addresses are scorned are less severe than those of the emendator whose darling conjecture is accepted by no one. His attitude tends to be, as Miss Tallulah Bankhead so well expressed it, “To hell with criticism: praise is good enough for me.” Extravagant expectations of this kind are, in the normal course of human affairs, doomed to disappointment, and the man of philosophic mind may draw much consolation from the reflexion that his reviewers and his employers are two different sets of men. But for the world of literate men and women, what is gained by the successful performance of the textual critic’s task?

Here I shall, with your permission, invoke the privilege accorded to old age ever since Homer drew the character of Nestor, of talking of oneself. I have produced critical editions of two Latin authors, Macrobius and Martianus Capella. Neither is an author of the first rank, yet both will find readers for different reasons. Macrobius, as we have seen, preserves a great deal of material from Greek and Latin literature; he chose well the authors whom he decided to plagiarize, and where his sources have perished he may be thanked for his choice, if not for his methods. Martianus Capella also preserved here and there pieces of ancient learning which otherwise would never have been known to the Latin middle ages, during which his encyclopaedic work enjoyed an enormous vogue. I will try to say what I think was achieved by those two undertakings.

The text of Macrobius was not improved very much. A few better readings appeared here and there, but in the main the text remained as readers were accustomed to see it. The progress made was that the manuscript basis for the text was now put before the reader. Of the two preceding editors, one had examined a large number of manuscripts and editions, but the people who collated manuscripts for him were incredibly negligent and missed two-thirds of the variant readings; the other, although his manuscript collation was of admirable accuracy, used only two manuscripts and took no account of any others. Hence what was needed was a survey of the manuscript evidence. Because the text was (apart from several lacunae) very well preserved, this work did not make us believe new things about the text of Macrobius, but it provided us with observational grounds for believing what we already did believe.

With Martianus Capella the state of affairs was different. A good edition had been produced, after 40 years of devoted work, by Dr Adolf Dick, who was headmaster of the Cantonschule of St Gall in Switzerland. He used nine early manuscripts, and he recorded all their variants accurately. His one shortcoming was that he did not understand how full of lies those manuscripts were. Since the work of Martianus was used from the 9th century on for instruction in schools, and since the text of the sole manuscript in which it had reached the Carolingian renaissance was deplorably corrupt, the schoolmasters at once began to correct the mistakes so as to provide their boys with a readable text. In doing so they filled the manuscripts, even very early ones, with conjectural readings which were in some cases very clever but which covered up the original damage to the text. The task of the critic was here to find, if possible, manuscripts which had not been tampered with and in which the faults of the archetype could still be clearly seen. There are in fact some six or seven among the 250 manuscripts which are free in this way from deliberate alteration. With the assistance of the catalogue of manuscripts drawn up by Claudio Leonardi and the penetrating study of the earliest among them by Jean Preaux in Brussels, it was possible to find what those manuscripts were and to use their testimony, together with the collateral evidence of those writers whom Martianus had used as sources, to purge the text of mediaeval fabrications which had persevered through every printed edition.

Something, I think, was gained for our understanding of Martianus Capella himself. He had traditionally been written off as one of the greatest asses ever to have set pen to paper, but upon careful examination it appeared that corruption in his text or in the texts of his sources accounted for many of his most remarkable blunders. It was unfair, for example, to blame him for assigning to Alexander a victory in Arabia instead of Arbela when it is obvious that Arabia was the reading of the manuscripts of his source Pliny the Elder, or to blame him for misunderstanding the text of Pliny as it stood in 19th-century editions, when those editions were following a conjectural supplement proposed by the renaissance humanist Ermolao Barbaro. I have been led to the opinion that he was not a fool and that he was making an intelligent and serious attempt to compress a liberal education into four or five hundred pages. This is what I think I have done: it is fair to say that other views have been expressed in print and that they are less favourable. But whether or not my work has been successful, I have enjoyed doing it, and the attitude of mind engendered in studying the transmission of Latin texts has been a source of great pleasure in looking for and sometimes stumbling over mistakes made by modern typists and compositors which throw light on the blunders of ancient and mediaeval copyists.

Also – though this has not much directly to do with the trade of textual criticism – I have enjoyed being surrounded by those whom I may call in plain English, not in the jargon of the lawcourts, my learned friends. From them, and often from my students, I have often learned to correct my opinions and to stock my head with as much wisdom as Providence had ever ordained that it should possess. If any of those benefits have ever been to the slightest degree returned, I am very happy, and I can wish nothing better to the young among us than that they may spend 40 years as interestingly and instructively and happily as I have spent my working life.