Jacob Howland

The Clitophon is the shortest dialogue in the Platonic corpus, and certainly one of the strangest. It is a tense encounter between the philosopher Socrates and the Athenian oligarchic leader Clitophon, who briefly haunted the Socratic circle. Their private exchange, somehow both intimate and cold, is a revealing enactment of the city’s ill-will toward Socrates: a little human drama that plays out while thunderheads of civic strife gather silently on the horizon. The dialogue shows why politics and philosophical inquiry both need, and are threatened by, each other – why their fates are bound together, as in a tragedy. And that essential knowledge illuminates our current circumstances.

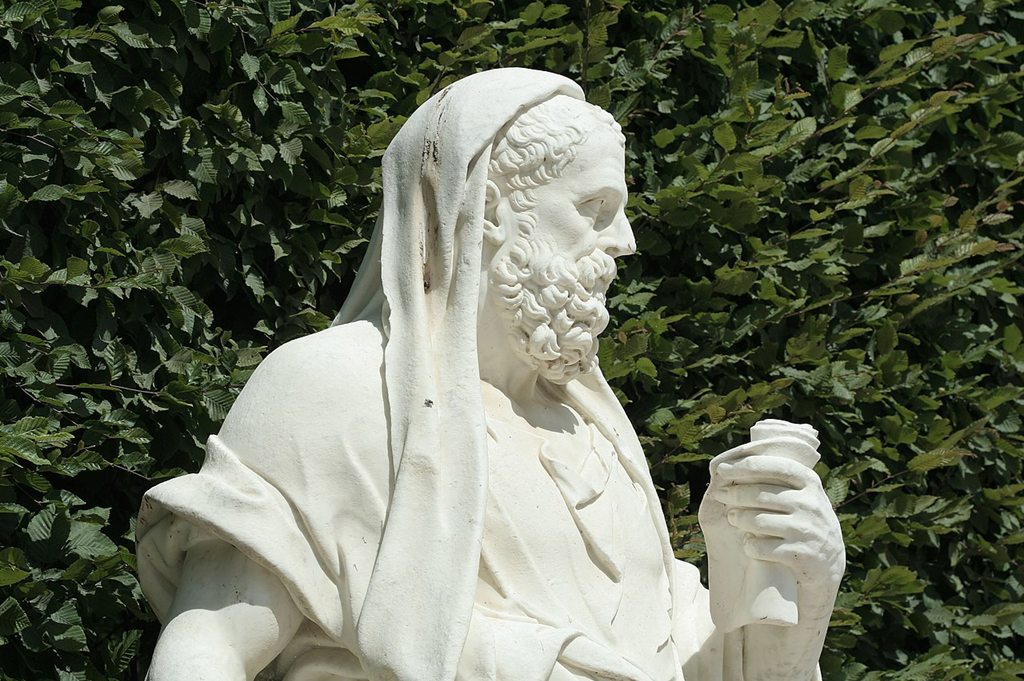

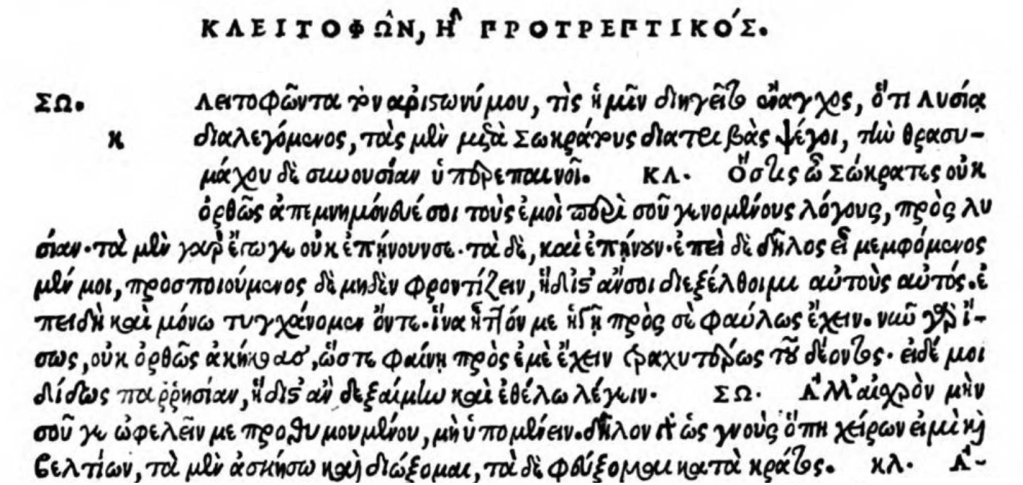

The Clitophon wastes no time getting started. Socrates immediately puts his interlocutor on the spot: he’s heard that he’s been running him down to the speechwriter Lysias while praising Thrasymachus, a theoretician of technocracy. Clitophon responds with a performance both personal and abstract, combining wounded indignation with something like an argument in a textbook on logic. Socrates, it seems, lifted him up and then let him down hard. He spoke “most nobly” when, “like a god on the tragic stage [ἐπὶ μηχανῆς, epi mēchanēs],” he exhorted the Athenians to pursue virtue, and justice above all. But neither he nor his philosophical companions can explain what justice is without arguing in circles and contradicting themselves. Maybe Socrates doesn’t know, or maybe he is unwilling to share his knowledge – in which case, Clitophon darkly implies, he would be guilty of injustice to him, and to the city he serves. Socrates remains silent in the face of this criticism, and the dialogue ends.

Why does Socrates, who is always eager to discuss virtue, justice, and his own shortcomings, have nothing to say to Clitophon? The answer to this question is to be found in the dialogue’s historical entanglements and literary allusions, which establish its probable political context and dramatic date. These clues suggest that the Clitophon is set at a moment when the middle ground of politics in Athens – the public arena of dialogue and debate about matters of primary civic import – is verging on total collapse. Today that moment is easy to imagine, and has in some ways already announced its approach. The Clitophon is indispensable to understanding our predicament, and perhaps avoiding the suffering that attends such collapse.

Historical Context and Dramatic Date

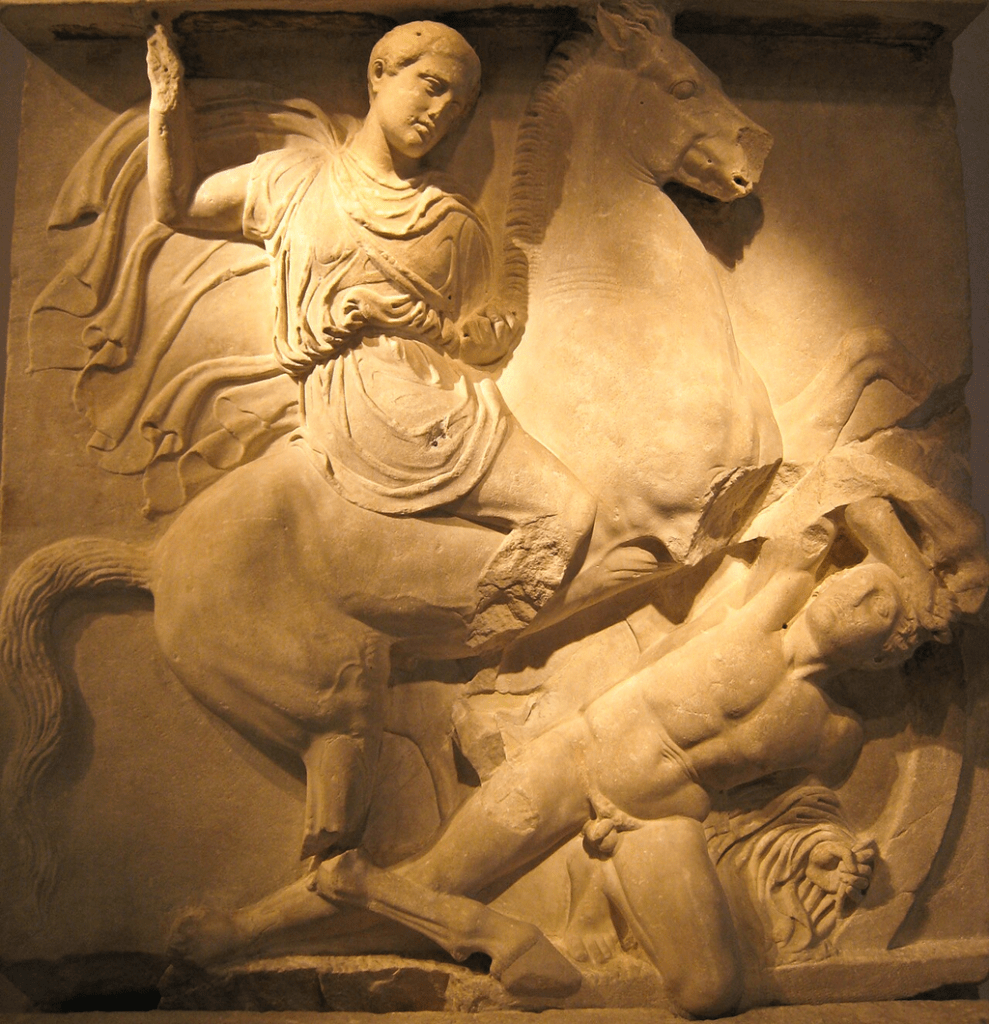

The four men named in the Clitophon are all actual historical figures. They are all present in the Republic, too – a dialogue saturated in the bloody history of the Thirty, the Spartan-backed oligarchy that came to power after the Athenian surrender in 404 – and all suffered under, or were implicated in, the violence of late-5th-century Athenian democracy and oligarchy.

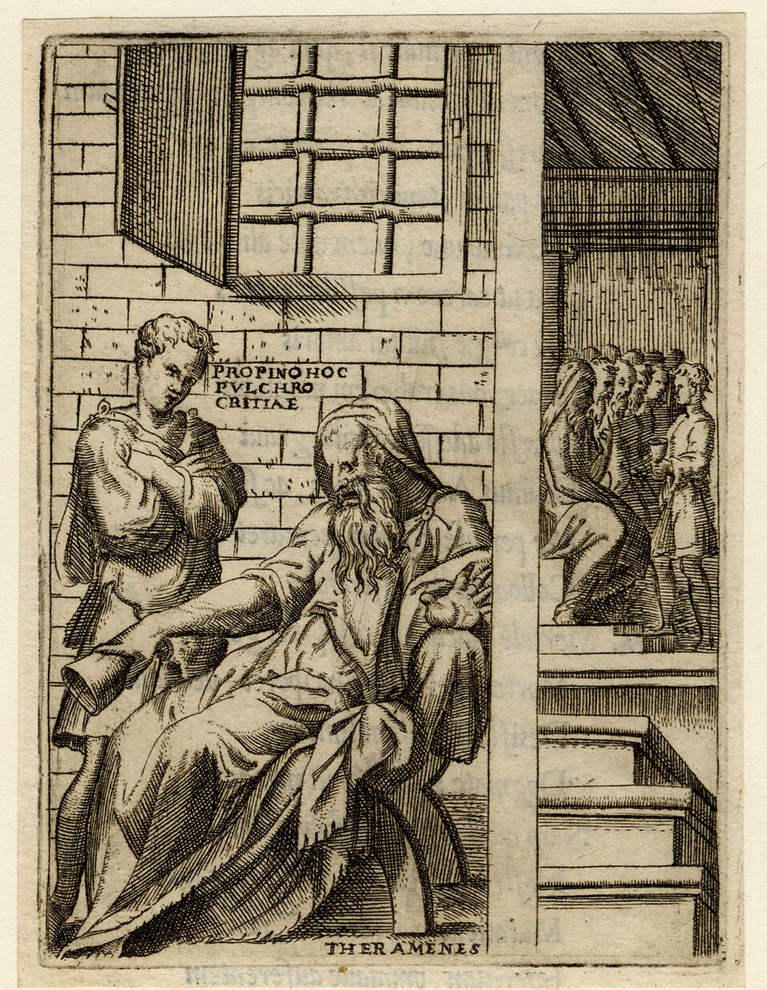

Thrasymachus was a citizen of Chalcedon, a subject city of Athens that decamped to the Spartans during the Peloponnesian War, and that the Athenians would have destroyed completely were it not for the intervention of the Persians. Lysias fled Athens after his brother Polemarchus was robbed and murdered by the Thirty, who executed 1,500 Athenians over the course of their eight-month rule. Socrates’ execution under the restored democracy was partly attributable to his association with Plato’s cousin Critias, the Thirty’s leader. Clitophon was an associate of Theramenes, one of the Thirty, and would certainly have supported the oligarchy when it came to power. But Critias had Theramenes put to death in 404, after he objected to his murderous purges; Clitophon dropped out of the historical record around the same time, and may have suffered the same fate.[1]

The Clitophon also echoes the political and philosophical condemnations Socrates faced at the end of his life. Clitophon’s remark that Socrates speaks from on high like a god on the stage recalls Aristophanes’ Clouds (staged in 423 BC), to which Socrates traces the charge of impiety he faces at his public trial, and in which he appears suspended in a basket, “look[ing] down on the gods.” Clitophon questions the companions of Socrates who are held in especially high repute, and publicly exposes their ignorance; Socrates explains in the Apology that he proceeded in a similar manner when he interrogated the politicians after learning about the Delphic Oracle’s response to Chaerephon. And uncharacteristically, Socrates speaks just twice in the Clitophon, early and briefly. He is similarly reserved in the Sophist and Statesman, dialogues concurrent with his criminal indictment, in which the Eleatic Stranger characterizes him as a sham philosopher and a bad citizen – in other words, a sophist.

Taken together, these historical and literary reverberations suggest that the Clitophon is, dramatically speaking, a late dialogue. And while the matter allows only for informed speculation, it seems to be set soon after the Thirty came to power, when the regime had already begun its political persecutions. Clitophon’s association with the regime would explain his aggressive interrogation of the Socratics, whom the Thirty regarded with suspicion. (The Thirty outlawed teaching the art of speech, and specifically forbade Socrates to speak with anyone under thirty years of age. Whether Clitophon played any part in these decisions is an open question.) It would also explain the oddity of Socrates’ – and the dialogue’s – first words, which mimic, perhaps in a spirit of defensive anticipation, the sort of formal accusation the Thirty might make: “‘Clitophon the son of Aristonymus,’ someone was just telling us [who?], ‘was conversing with Lysias and criticized spending time with Socrates, while praising to the skies the company of Thrasymachus.’” And it would explain why Clitophon takes pains to persuade Socrates that he is not “foully disposed” (φαύλως ἔχειν, phaulōs echein) toward him, for his political affiliations would have made him eminently capable of harming his enemies.

Clitophon and Thrasymachus in the Republic

Clitophon’s intellectual and political affinity with the Thirty becomes clear in the Republic, a dialogue in which the question “What is justice?” is no less central than in the Clitophon. Clitophon takes Thrasymachus’ side in his argument with Socrates, and his sole intervention in the Republic is deeply revealing. He argues that each ruling group sets down laws for its own advantage, and that obeying the law is just; justice is therefore nothing other than the advantage of the stronger. (In listing the kinds of rule, he mentions tyranny, democracy, and aristocracy, but omits oligarchy – as if to suggest that oligarchy simply is rule by the best.)[2] But Thrasymachus admits that rulers sometimes mistakenly set down laws and issue commands that are bad for them; in those instances, Socrates observes, it would be just to do what is disadvantageous for the rulers. When Polemarchus applauds Socrates’ point, Clitophon replies “If it’s you who are to witness for him, Polemarchus.” It’s a nasty comeback: Polemarchus is a wealthy resident alien, a group later persecuted by the Thirty, and Clitophon questions his right to be heard in what he frames as a quasi-judicial proceeding. Like the Thirty, Clitophon’s instinct is to restrict speech. Given Polemarchus’ ultimate fate (and perhaps also his own), his subsequent insistence that “to do what the rulers bid is just, Polemarchus,” is chilling.

The immediate sequel connects Clitophon still more closely with the Thirty. Clitophon seems to endorse subjectivism when he defends Thrasymachus by claiming that he maintained “the advantage of the stronger is what the stronger believes to be his advantage”. Although Thrasymachus denies that this is what he said, it is nevertheless what he meant, for he defines the ruler in such a way that he cannot be mistaken regarding his own advantage. He asserts that none of the craftsmen “in precise speech” makes mistakes, as that would imply a failure of knowledge; “the ruler, insofar as he is a ruler,” therefore never makes mistakes. But ruling unavoidably involves conjecture and guesswork. If it is an art, as Thrasymachus supposes, it is a stochastic one; yet he treats it as though it were a non-stochastic technē. He seems unaware that political matters are too variable and opaque to be measured by the standards of accuracy that apply to mathematics, or to yield definitive solutions, like problems in arithmetic.

Thrasymachus’ assumption that ruling is the exercise of inerrant technical knowledge or applied science echoes the conceit of Critias, who argues in the Charmides that sound-mindedness (σωφροσύνη, sōphrosunē) is a meta-science of sciences that would allow only genuine forms of knowledge into human life. This knowledge would guarantee (in Socrates’ summation) that “every city [would be] beautifully governed,” and that we would “live out our life without error, both we ourselves… and all the rest who are ruled by us.” Yet it proves to be vacuous, as it has for its content nothing that is known by any particular science, but only the form of science as such.

Critias’ conception of governance by technocratic experts reflects the extreme intellectual abstraction that is the hallmark of ideological tyranny.[3] It rules out the public practice of philosophy, the quest for knowledge and wisdom that necessarily involves error. For it assumes adequate knowledge of justice and the science of government, not just in theory, but as an actual possession that warrants the rule of the oligarchy over which Critias presided. And it is a conception that Clitophon evidently shares.

Socrates’ Public Harangues

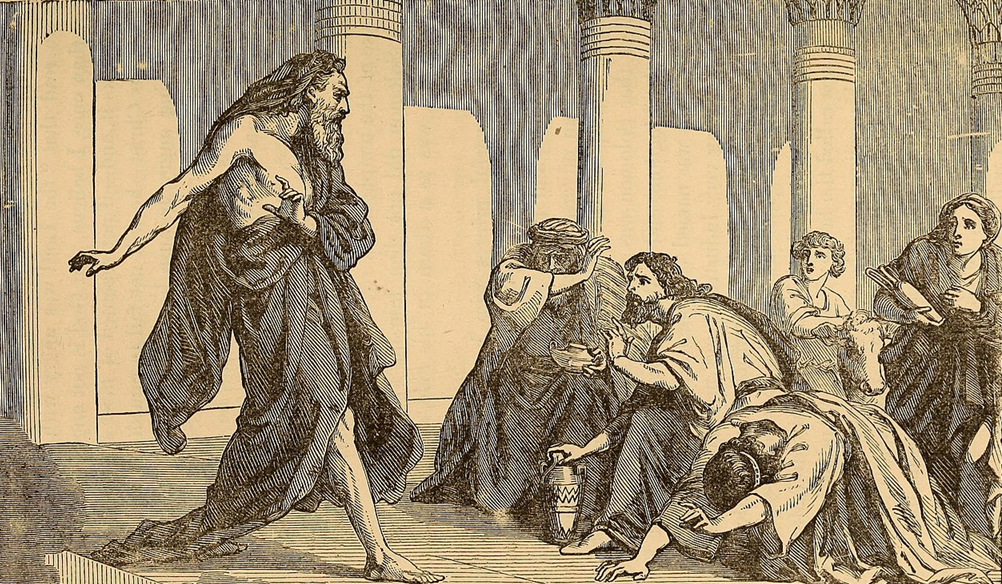

Clitophon begins his diatribe by explaining that he was often astounded when, “singing” like a god on stage, Socrates publicly reproached the Athenians. His amazement is understandable, for Socrates seems to have broken into everyday life in a way not otherwise seen in the Platonic dialogues. Speaking more like a Hebrew prophet than a Greek philosopher, he castigated everyone within earshot. “Whither are you borne, O human beings?” he began. “Are you not ignorant that you do nothing that you ought?” Clitophon explains that Socrates proceeded to rebuke his auditors for their neglect of justice and the “unmusicality” and “dissonance” of their conduct. His vivid description of their condition as civil strife (στάσις, stasis) and war, in which “brother lays hands on brother, and city on city… [and] they do and suffer the utmost,” makes it clear that the city is in dire straits.

The Socrates that Clitophon describes is a far cry from the man who engages in philosophical dialogue and disputation elsewhere in the pages of Plato. The pressure of the times has evidently forced his activity into new forms. Driven by desperation at moral collapse and political chaos, he has stepped into the public realm in an unaccustomed manner. The Apology, in which Socrates describes doggedly trying to make “whomever among you I happen to meet” ashamed to care more for money, reputation, and honor than for their souls, is the only other dialogue that refers to this kind of public activity. This fact, too, suggests that Socrates’ harangues were a relatively recent development at the time of his trial.

In Clitophon’s telling, Socrates insisted that injustice is involuntary, contrary to what his auditors believed. This is a question with direct political ramifications. For if injustice is voluntary, it can be dealt with only by force. What is to be done with people who deliberately choose what they know to be “disgraceful and hateful to the gods” – people who would seem to be irredeemably evil? The Thirty’s answer was, in Lysias’ words, “to purge the city of unjust men” – or at least of those groups, starting with so-called “sycophants”, whom the regime alleged were unjust.[4] But if injustice is involuntary and springs from ignorance, it is potentially correctible by reflection and dialogue. That is the political hope and promise of Socratic philosophizing, which, in any healthy community, must have a place in the assembly and the marketplace, as well as behind closed doors. Socrates therefore concluded his harangues by urging “every man privately and at the same time all the cities publicly” to pay greater attention to justice.

Clitophon’s Interrogations

Clitophon says that he greatly admired Socrates when he said these things; when he admonished those who pay no attention to the part that rules (the soul), while concerning themselves with that which is ruled (the body); and when he opined that those who don’t know how to make use of something should not use it in any way. And he declares that Socrates spoke finely in saying that one who doesn’t know how to make use of his soul “should hand over the rudder of his thought to another who has learned the art of piloting human beings [κυβερνᾶν, kubernān, the origin of English “govern”], which indeed is the name that you often give to politics, saying that this same art is that of judging and justice.” The Thirty, of course, supposed that they possessed expertise in judging individuals as well as governing the city.

Claiming to have been awakened by Socrates’ exhortations, Clitophon attended to what came next: determining the nature of justice. But his assertion that he proceeded after the manner of Socrates falls flat, for his inquiries, far from being open-minded efforts to arrive at truth, were tendentious and eristic. Like someone who desires to show that he’s vanquished the very best opponents in argument, he makes a point of saying that he approached “those of whom you have an especially high opinion”, and that he interrogated those companions of Socrates who are “reputed to be the most formidable in these matters” or “reputed to speak in a most accomplished manner”. Nor does he ever question his assumption, shared with Thrasymachus and Critias, that justice is a kind of technical knowledge. Specifically, it is an art that “produces just men”, just as carpentry produces houses – an art, one might say, of engineering souls. (Socrates had compared justice to piloting – a practical rather than a productive art that, as he notes in the Republic, requires attention to the whole, including the heavens, the stars, the seasons, and the winds.)

Clitophon’s contribution to clarifying the nature of justice is strictly negative: he shows that Socrates’ companions are unable to say precisely in what the art of justice consists, and he does so in the presence of others who are quick to show their hostility to them. When the Socratics maintained that the product of justice is the advantageous, the needful, the beneficial, and the profitable, he refused to accept these terms, just as Thrasymachus did in arguing with Socrates in the Republic. Finally, one of them asserted that the unique result of justice is “to produce friendship in cities”, and in particular “likeness of mind” (ὁμόνοια, homonoia). But, when pressed, the man was compelled to maintain that this unanimity must be based on shared knowledge, for shared opinion, when it is mistaken, has often proved harmful.

This reply was itself a mistake. For the like-mindedness that constitutes the community of Socratic philosophizing springs not from knowledge, but from the shared conviction that the pursuit of wisdom and knowledge through open inquiry and civil discourse is essential for the health of individual souls and the political community as a whole. This point escaped the notice of the bystanders. They seized instead upon the fact that the argument had circled back to its beginning, for the question at issue was the particular kind of knowledge that makes for justice. Their response to the poor fellow who fell into this trap was decidedly uncivil: they “were ready to fall upon [ἐπιπλήττειν, epiplēttein]” him. Perhaps they were encouraged by Clitophon’s antagonistic interrogations.

The Judgment and Justice of Socrates

The Socratics are united by their devotion to the search for wisdom through dialogue. No special expertise in justice is needed to maintain their philosophical community, which is sustained not by technē but by erōs. Yet the intrinsic character of this community is invisible to Clitophon, who condemns its failure to produce results in the form of knowledge, and calls that judgment justice. Clitophon has no patience for the process of learning by jointly fumbling toward the truth in discussion and argument. It is no small irony that he condemns this activity, and thereby the greatest part of liberal education, in the name of knowledge.

Clitophon goes on to express his frustration with yet another inconsistency. When he finally questioned Socrates himself, he was told that “it is characteristic of justice to harm enemies and do good to friends”. But later, “it appeared that the just man never harms anyone.” What explains this contradiction? Socrates’ first reply offers a political perspective on justice; his second, a philosophical one. Taken together, these two statements summarize the problem at the heart of the Clitophon: the fraught relationship between a politics that supposes it has definitive knowledge of who are enemies and who friends, and a philosophy that does not.

Clitophon tells Socrates that either he doesn’t know what justice is – an opinion he insists he himself does not hold – “or you are unwilling to share the knowledge with me.” He does not have to explain that this unwillingness would be unjust, and would certainly generate ill-will in him and his fellow citizens. He concludes his diatribe by asserting that, for one who has been exhorted to pursue virtue, Socrates is “almost even an impediment to arriving at the goal of virtue and becoming happy.” Those are the dialogue’s last words.

Why doesn’t Socrates reply to Clitophon? His silence has its own dramatic eloquence; it is a happy accident that it anticipates the Thirty’s suppression of his public voice. Socrates might have thought that he would risk his life in speaking his mind, although that alone wouldn’t have stopped the courageous man that Plato portrays in the dialogues. Are we to infer that he believed it would be best to wait for a time when he could have his final say in public, as he does in the Apology, where he goesout with a bang?In any case, Socrates implicitly answers Clitophon with a judgment of his own. For he has evidently realized that it would be futile to say anything at all – that nothing can now save the middle ground of politics from sinking into a sea of enmity and violence.

Lessons of the Clitophon

The Clitophon dramatizes the conflict between philosophy and technocracy as a tyrannical ideology, or rule by specious “science” that is incapable of sustaining its claim to authority without compulsion and violence. The physicist Richard Feynman defined science as “belief in the ignorance of experts”, suggesting that we should trust them when they profess ignorance in matters pertaining to their area of specialization, and doubt them when they claim only knowledge. But this Socratic knowledge of ignorance is in short supply among our technocratic elites.

Anthony Fauci, who asserted at the height of the Covid pandemic that “a lot of what you’re seeing as attacks on me quite frankly are attacks on science,” notoriously exemplified this failing. While Feynman recognizes that science is essentially open-ended, fallibilistic inquiry, Fauci’s “science”, like Thrasymachus’ craftsman “in the precise sense”, cannot be mistaken. And just insofar as he is the science – the living embodiment of public health expertise – his authority is unimpeachable.

Feynman and Socrates are philosophical and erotic learners; Fauci and Clitophon are political and thumotic knowers – a ruling type that has, in the last decade, multiplied with alarming rapidity throughout the West. The former seek truth, while the latter produce it, like legislation, and defend it by manufacturing an elite consensus of experts and intellectuals. To this end, they try to silence their critics through censorship, cancellation, and intimidation – means that are widely deployed today, when all spheres of society and culture are riven with conflict. For like-mindedness that is not freely elicited by dialogue, but externally imposed by compulsion, is a simulacrum of justice whose most evident accomplishment, the increase of rancor and division, is in fact the work of injustice.

Clitophon’s combination of subjectivism and absolutism is another distinctive feature of our age, one whose paradoxical character is resolved in thinking through the Clitophon. For if there is only “my/our truth” and “your truth,” disputes about justice and other so-called “value judgments” can be settled only by the application of power. If their “truth” is to prevail without widespread violence, the few who rule in a technocracy – which is by definition oligarchic – must obtain the compliance of the many by employing indoctrination, censorship, and other tools of soft despotism. But such measures are as likely to promote violence as to suppress it.

Technocrats fear the community of philosophers because they call into question their claim to rule on the basis of knowledge, and despise them because they are useless in offering solutions to problems framed in the perspective of their oxymoronic political science. The epigones of Clitophon have now taken over our educational, political, and cultural institutions, and subjectivist absolutism has largely eclipsed the public practice of open inquiry and dialogue, the lifeblood of politics and philosophy alike. For an apolitical philosophy – one that withdraws from public discussion and debate about what is good and bad, advantageous and harmful, just and unjust – is as abstract, sterile, and intellectually untested as an anti-philosophical politics.

Will we go the way of the Athenians under the Thirty? How can we arrest society’s movement toward the abysmal silence of misology and violence, the silence that is prefigured at the end of the Clitophon? For us, today, this is the ultimate riddle of the Clitophon.

Jacob Howland served as Provost and Dean of the Intellectual Foundations Program at the University of Austin from 2022 to 2025. Before that, he was McFarlin Professor of Philosophy at the University of Tulsa, where he taught for 32 years. Howland is the author of Glaucon’s Fate: History, Myth, and Character in Plato’s Republic (2018); Plato and the Talmud (2011); Kierkegaard and Socrates: A Study in Philosophy and Faith (2006); The Paradox of Political Philosophy: Socrates’ Philosophic Trial (1998); and The Republic: The Odyssey of Philosophy (1993).

Further Reading

Jacob Howland, Glaucon’s Fate: History, Myth, and Character in Plato’s Republic (Paul Dry Books, Philadelphia, PA, 2018). This book reads the Republic in the light of the history of the Thirty and Plato’s presentation of Critias in the dialogues.

Mark Kremer, Plato’s Cleitophon: On Socrates and the Modern Mind (Lexington Books, Lanham, MD, 2004). This collection includes seminal essays on the dialogue by David Roochnik, Clifford Orwin, and Jan Blits.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Paul A. Rahe suggests this possibility in “Lysander and the Spartan Settlement, 407–403 B.C.” Ph.D. diss., Yale (1977) 198. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Thrasymachus may have assisted in overthrowing a democratic regime in the Aeolian city of Cyme. See Stephen A. White, “Thrasymachus the Diplomat,” Classical Philology 90 (1995) 307–27, at 319 and 326–7. His pro-oligarchic stance might have protected him from being targeted by the Thirty, as other foreign residents were. |

| ⇧3 | Critias “prefigures the modern totalitarian ruler, a creature who rules by abstractions.” (Eva Brann, “The Tyrant’s Temperance: Charmides,” in The Music of the Republic: Essays on Socrates’ Conversations and Plato’s Writings (Paul Dry Books, Philadelphia, PA, 2004) 66–87, at 81. Totalitarian regimes, Brann adds, promote “one schematic idea… [that] certifies itself and all other knowledge as within or without its pale.” |

| ⇧4 | Lysias 12.5; cf. Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.15–4.8. Brann (as n.3) describes the Thirty’s reign of terror as “an early, perhaps the earliest, example of ideological purification” (“The Tyrant’s Temperance,” 69). |