Mateusz Stróżyński

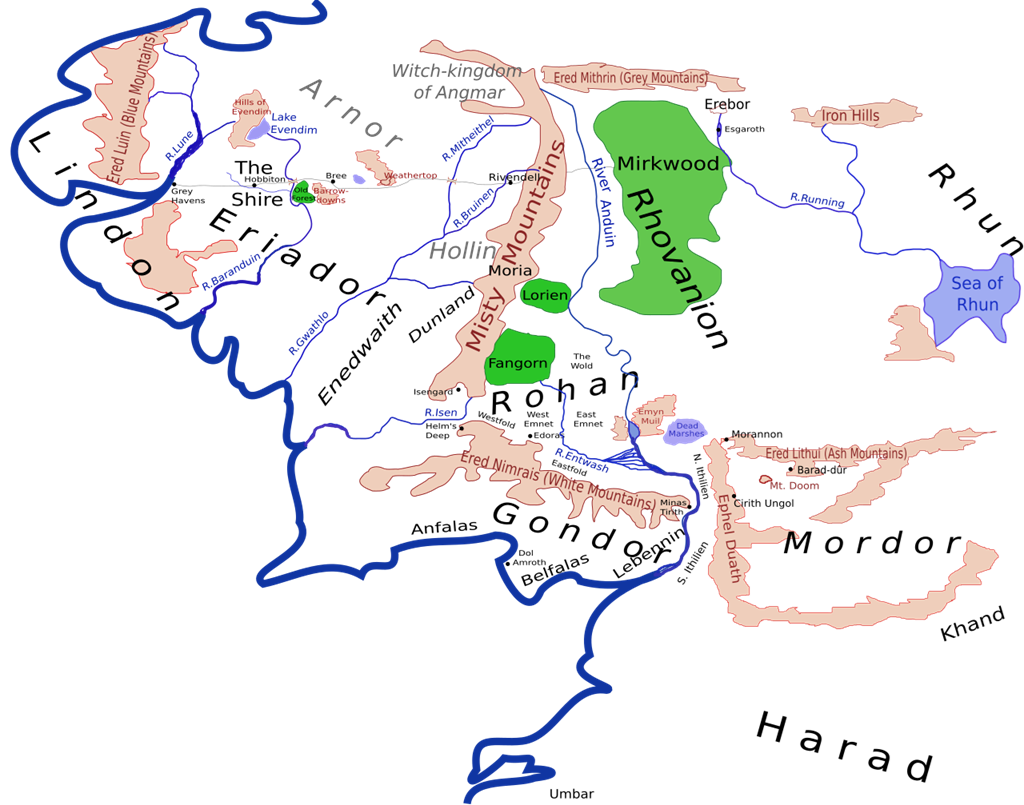

In his essay on the Lord of the Rings, John Kevin Newman draws parallels between Tolkien’s novel and the Argonautica, a Hellenistic epic poem by Apollonius of Rhodes. He points out that the Lord of the Ring is similar to the Argonautica in terms of its being a mythical journey eastward to obtain a treasure, although the last point is reversed: the treasure must be lost, not acquired. In The Hobbit, however, which Newman does not examine, the treasure in fact must be acquired; moreover, a dragon-guardian appears, just as in the Argonautica, so the analogies seem even stronger. But Newman overlooks the theme of return and the circular structure of the narrative, which seems equally significant in Tolkien. Having written about the presence of the ancient epic tradition in The Hobbit in two previous pieces (here and here), in what follows I would like to offer some thoughts on the ancient epic context of the motif of nostos in this famous pair of Tolkien novels.

In the very title of his first novel, Tolkien emphasizes the circularity of the central event, Bilbo’s journey: The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. Bilbo begins his journey at home, in his homeland – that is, in his hole at Bag End – and ends it in exactly the same place. At the end of the novel, Tolkien writes that on “one autumn evening some years afterwards” Bilbo is sitting in his study, occupied with writing his memoirs, which he entitles There and Back Again (see Chapter Nineteen, “The Last Stage”). The final scene of The Hobbit is a conversation between Bilbo and his friends, the wizard Gandalf and the dwarf Balin, who are visiting him. Tolkien thus underscores the hero’s return to the starting point, to home, but at the same time points out to the reader how much the hobbit has changed during, and as a result of, his adventure – the house is the same, but its inhabitant is no longer the same person. Gandalf says: “Something is the matter with you! You are not the hobbit that you were.”

The motif of the hero’s journey is already present at the beginning of the ancient epic tradition: he first leaves his safe and beloved home and homeland to wage war in a distant land; then, after wandering for many years, he finally returns to the place where his adventure began. The Odyssey, however, does not actually tell this kind of story. Its theme is the return from Troy, as is evident in the narrative’s composition.

In the first book of the Odyssey, we see Odysseus not in his house on Ithaca, but in a kind of fake home – or even the very antithesis of home and homeland – since he is imprisoned on the island of Calypso. There the hero is provided with every comfort, with a woman who wishes to be his wife, and with the tempting prospect of immortality; yet he does not feel at home. Instead, he thinks constantly of returning. From there, in Book Five, the hero sets out on his journey after the gods intervene in the action. Both formally and thematically, then, the Odyssey tells the story of someone who returns home – not of someone who leaves a comfortable home, and then returns to it.

The structure of Virgil’s Aeneid is in fact quite similar, though certain differences between the two epic poems in this regard should be noted. in Virgil’s case, the hero’s home – and homeland – has been destroyed, and he seeks a place where he might found a new one. Nevertheless, in Book Three there appears an intriguing prophecy from Phoebus, who proclaims:

Dardanidae duri, quae vos a stirpe parentum

prima tulit tellus, eadem vos ubere laeto

accipiet reduces. antiquam exquirite matrem.

hic domus Aeneae cunctis dominabitur oris

et nati natorum et qui nascentur ab illis.

O breed of iron men,

ye sons of Dardanus! the self-same land

where bloomed at first your far-descended stem

shall to its bounteous bosom draw ye home.

Seek out your ancient Mother! There at last

Aeneas’ race shall reign on every shore,

and his sons’ sons, and all their house to be.

(Aen. 3.94–8; translation by Theodore C. Williams, 1908.)

The prophecy suggests that Aeneas is, in fact, returning to the archetypal home as a symbol of primordial safety, which Virgil here equates with the body of Mother Earth. Both the Odyssey and the Aeneid, however, are narratives that begin, as it were, in exile, already outside the home.

The motif of the hero’s return (νόστος, nostos), present already in the Odyssey, was the central theme of the Nostoi (Νόστοι), the cyclic epic poem meaning “return journeys”, as Athenaeus tells us (7.281b). It was also taken up by Athenian tragedians (for example Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, Sophocles’ Trachiniae, and Euripides’ Heracles). A crucial aspect of some of these nostoi is the fact that, upon returning home, the hero finds the situation significantly altered – often, as in the case of Agamemnon or Odysseus, even in ways that are dangerous for himself. Oliver Taplin distinguished between two varieties of return: from a relatively secure situation to an unexpected disaster encountered at home, and from a disaster to a secure home.[1]

In The Hobbit, the author employs the nostos scheme that Taplin has called a “return to catastrophe,” although in Tolkien’s case, of course, there can be no question of any real catastrophe – it is merely a return to a home that has ceased to be safe. Upon reaching the Shire, Bilbo realizes that he has been declared dead and that his property has been put up for auction. Being declared dead can be seen as a kind of neutralization of the terror of epic death, as in the story of Agamemnon’s return, and it is subsequently transformed into a comic situation. At the same time, the obvious reference arises to Odysseus’ return, for he too was declared dead, which enables Homer to depict striking anagnorismos (recognition) and the confrontation between the hero returning “from the dead” and the suitors plundering his property.

In The Hobbit there are no suitors, only local villains – Bilbo’s cousins, the Sackville-Bagginses – who “really had wanted to live in his nice hobbit-hole so very much” (Chapter Fourteen). Compared with Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, however, these figures are petty antagonists. In the Lord of the Rings, on the other hand, the situation is much more serious, for the Shire is destroyed by the wizard Saruman the White, under the disguise of “Sharkey”, who takes revenge on the hobbits for what he considers to be their part in the destruction of his own home, Isengard. The hobbits are genuinely threatened: they must fight a battle in which there are wounded and dead, and the most painful aspect is the “industrialization” of the Shire – the destruction of its idyllic, paradisiacal nature through a thoughtless adoration of technology. The destruction of the Shire has a profound, symbolic significance in the novel:

“This is worse than Mordor!” said Sam. “Much worse in a way. It comes home to you, as they say; because it is home, and you remember it before it was all ruined.”

“Yes, this is Mordor,” said Frodo. “Just one of its works.”

(The Lord of the Rings, Vol. 3, Book 6, Chapter Eight: “The Scouring of the Shire”).

What is at stake here is the intrusion of evil into what is most beloved, pure, intimate – home and homeland. This contrasts with the earlier depiction of hobbits as beings living almost in a state of paradisiacal innocence – far from wars, great history, the affairs of the Wise and of the Elves. Their childlike world is attacked by a great evil – they are put to the test, and fall. Even if some of them pass the test, paradise is lost. For this reason, the restoration of the Shire symbolically represents redemption, the healing of the consequences of sin, although the hobbits no longer regain their former innocence. They acquire the bitter wisdom of maturity, embodied most fully in Frodo himself, the Ring-bearer. The healing of wounds becomes possible thanks to Galadriel’s gift to Sam – a bit of the soil from Lórien. Here too, transcendence enters the scene, represented by the daughter of Finarfin; here too, grace is necessary, some trace of Valinor, because ordinary human effort is insufficient to repair the destruction brought about by the folly and perversity of hobbit hearts that followed Sharkey – the tempter.

The motif of “the Scouring of the Shire” is therefore crucial to the epic design of Tolkien’s work, just as the analogous motif – again, in the Odyssey – of the necessity of undertaking another journey. Immediately after regaining his home, Odysseus must set out, at the command of the prophet Tiresias, on another journey to appease the wrath of Poseidon. He sets out with an oar on his shoulder, to find a people who do not know the sea and will therefore suppose the oar to be a winnowing fan. Only then will Odysseus be able to end his wanderings, to return home for good and await in peace the gentle death that will come to him from the sea (Od. 11.121–37). Frodo, too, must undertake another journey – to Valinor – which is likewise intended to bring about the ultimate healing of his wounds and the peaceful awaiting of “death from the sea” in the Blessed Realm. In The Hobbit, the motif of return is at least as important as that of setting out “into the world”. He would employ the same strategy on a broader scale in The Lord of the Rings, where everything – adventures, war, and “troubles” at home – would assume correspondingly greater proportions.

At this point, one may ask to what extent the ancient motif of the epic hero who fights and wanders outside his home, and then returns to it, is present in Tolkien’s novels. Here, with exceptional clarity, we encounter again the problem of the “leaf-mould of memory”, that I mentioned in my previous essays on Tolkien and Homer. In the case of the motif of leaving home and returning to it, the problem is all the more difficult to resolve because it is by no means a motif strictly bound to the epic genre. Joseph Campbell argued, famously, that this is an archetype present in most mythologies and religions, inscribed in the universal structure of the myth of the hero, who first lives as an ordinary person, happily, in his ordinary home, then enters a symbolic world of struggle, wandering, initiation, and inner transformation, and finally returns to a home that turns out to be both the point of departure and the point of arrival. The hero returns the same – and at the same time, not the same.[2]

However, it is impossible to overlook the fact that, in Western culture, Odysseus functions as one who leaves home and returns to it, and that the classical tradition, in addition to Norse mythology, was an important part of Tolkien’s formation as a young man. In light of this, I think it is legitimate to point out the similarities as well as the differences. The Odyssey (and, close behind, the Aeneid) remains the most well-known story in our culture about a hero’s journey “there and back again” – even if the hero is the very opposite of a hobbit, and the Odyssey itself contains only the way “back again.

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His most recent books are Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World: Faces of Being and Mirrors of Intellect (Cambridge UP, 2024) and Plato and Jesus, not Caesar: Metaphysics of Freedom and Tyranny in Younger Europe (Brill, Leiden, 2026)..

Further Reading:

Alongside my two earlier pieces on Tolkien and epic – “Homeric allusions in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit” (here), and “The fall of Smaug and the Heel of Achilles” (here), the following should be of interest:

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Pantheon, New York, 1949).

H G. Evelyn-White, “The myth of the Nostoi,” Classical Review 24 (1910) 201–5.

H.L. Tracy, “Vergil and the Nostoi,” Vergilius 14 (1968) 1–16.