Robin Alington Maguire

Part II: Problematic issues in the narrative

This is Part II of a two-part article. “Part I: Analysis of events” can be found here.

Introduction

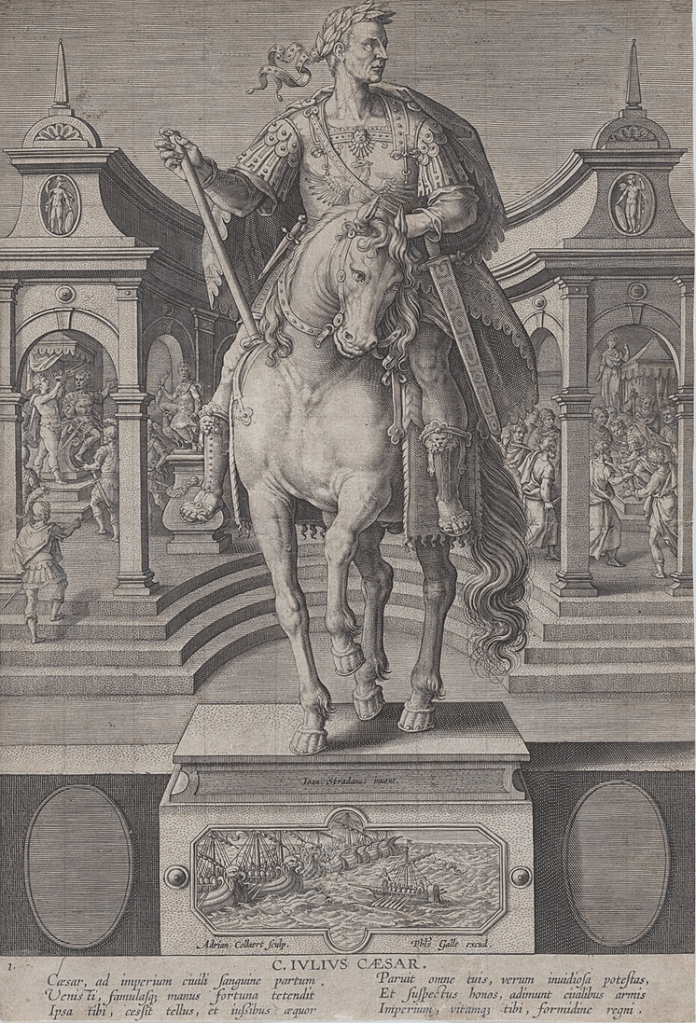

In 49 BC, Julius Caesar stood at the head of a Roman legion on the banks of the Rubicon River, which separated his allocated province of Cisalpine Gaul from Roman home territory. Crossing the river under arms would take his dispute with the Roman Senate out of the political sphere and into the realm of armed conflict. The ancient accounts of this episode are sufficiently detailed to enable us to reconstruct in detail what happened, and that was the subject of Part I of this article. However, the original accounts on the face of it are marred by several items which may make little sense to a modern reader. These matter because they cast doubt on the realism of the other information given.

In what follows I offer explanations for the problematic aspects of the original narratives, leaving the ancient authors to supply a clear and rational narrative as analysed in Part I. English translations of the relevant extracts from ancient authors are set out there too.

There are three areas of difficulty to be considered in the Rubicon story:

Caesar indecisive

Plutarch, Appian and Suetonius all tell us that Caesar stood on the banks of the Rubicon in a fit of uncertainty and indecision, talking to his companions of the evils which would follow an armed crossing into Roman territory. Caesar and his forces paused on the riverbank for some time, and this delay is presented by the writers as a symptom of Caesar’s indecision.

At the start of risky ventures Caesar was known more for reckless haste than introspection and uncertainty, so these passages call for explanation.

Caesar’s journey to the Rubicon

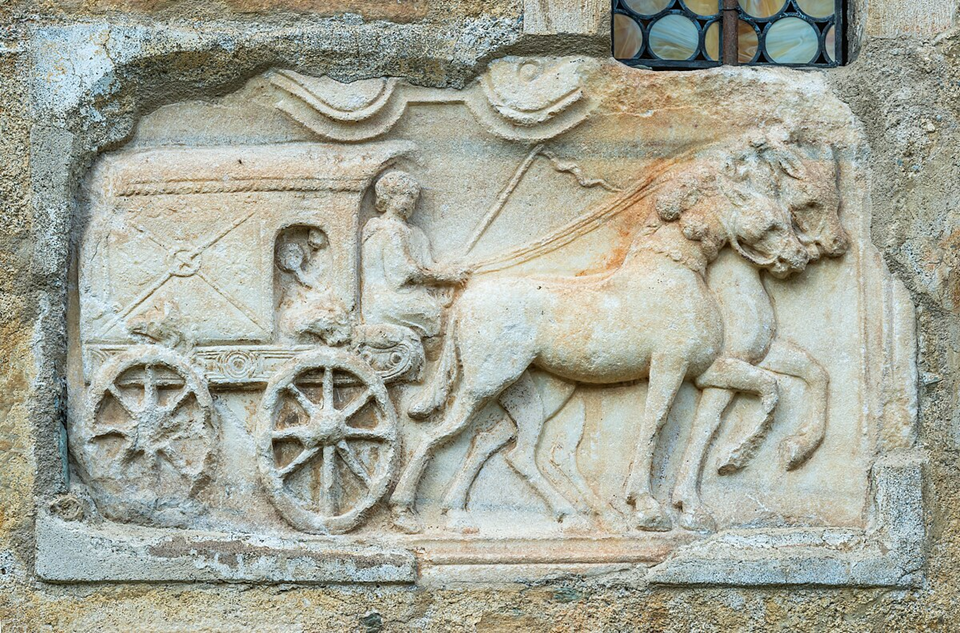

Suetonius describes Caesar’s journey from his base at Ravenna to the Rubicon:

It was not until after sunset that he set out very privily with a small company, taking the mules from a bakeshop hard by and harnessing them to a carriage; and when his lights went out and he lost his way, he was astray for some time, but at last found a guide at dawn and got back to the road on foot by narrow by-paths. (Suet. Div. Jul. 31, tr. J.C. Rolfe, Loeb, 1913)

This manner of proceeding seems unlikely for the mighty proconsul and military commander and casts an unhelpful air of farce over the course of events if left unexamined.

Phantasmal apparition

Suetonius has Caesar’s supposed mood of doubt by the Rubicon broken by a strange occurrence.

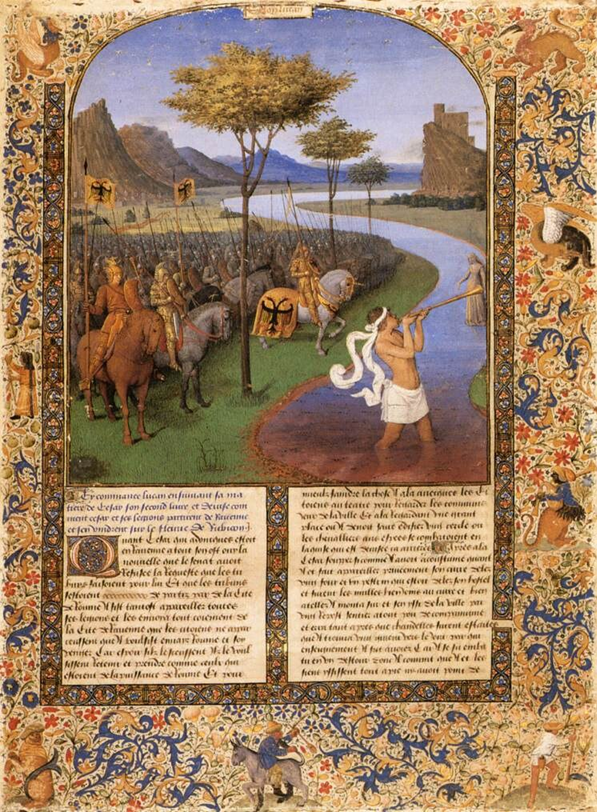

As he stood in doubt, this sign was given him. On a sudden there appeared hard by a being of wondrous stature and beauty, who sat and played upon a reed; and when not only the shepherds flocked to hear him, but many of the soldiers left their posts, and among them some of the trumpeters, the apparition snatched a trumpet from one of them, rushed to the river, and sounding the war-note with mighty blast, strode to the opposite bank. Then Caesar cried: “Take we the course which the signs of the gods and the false dealing of our foes point out. The die is cast,” said he. (Suet. Div. Jul. 32)

This passage, which is not replicated by Plutarch or Appian, does most of all to cast doubt on whether the story of the Rubicon should be seen as a useful historical source or as more of an allegorical fable.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus and Gaius Asinius Pollio

Suetonius (c.69–c.123) was a Roman scholar and prolific author who benefited from the patronage of Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Younger) and served the emperors Trajan and Hadrian as a literary secretary.

The most important of the works of Suetonius to have survived, almost intact, is De vita Caesarum (The Lives of the Twelve Caesars) which chronicles the lives of Julius Caesar and Rome’s first eleven emperors from Augustus to Domitian. We owe our knowledge of De Vita Caesarum to one single manuscript known to have been in existence at the beginning of the 9th century. The work was first translated into a modern language (French) in 1381 with the first English version appearing in 1606.

Suetonius clearly based his biographies on extensive and careful research, benefiting in some cases from his access to original documents held in the imperial archives. For example, he is able to comment on the handwriting and spelling of the Emperor Augustus. Where his factual statements can be checked against other evidence they generally turn out to be correct and, unlike many other ancient historians, he often supplies direct quotations from his sources. However, he has been criticised for including material seen as gossipy or scandalous, as well as accounts of supernatural occurrences. To my mind, Suetonius did not allow himself to invent material but was inclined to adopt the most colourful of the sources available to him, especially if they included an element of the supernatural. His histories contain a profusion of omens and portents.

The areas of difficulty in the story of Caesar at the Rubicon which are the subject of this article all arise in Suetonius’ account of the life of Julius Caesar.

Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 BC–AD 4) was a Roman soldier, politician and writer whose history of contemporary events, now lost, was used as a source by subsequent writers. He was a member of Caesar’s entourage at the Rubicon.

Plutarch has Caesar at the Rubicon talking to his friends, “among whom was Asinius Pollio”, which looks like a direct quote from Pollio’s lost history, as otherwise it is hard to see why Plutarch would have singled him out. This suggests that in writing his history, Pollio referred to himself in the third person by name, following the example of Caesar in his own histories of the conquest of Gaul (De Bello Gallico) and the subsequent Civil War (De Bello Civili).

Incidentally, Pollio is mentioned half a dozen times by Suetonius in De Vita Caesarum, though not in the context of the Rubicon.

Caesar indecisive

Consideration of the three areas of difficulty in the original texts begins with the suggestion that Caesar had trouble making up his mind. In modern mentions of the Rubicon, much is invariably made of Caesar’s apparent doubt and indecision. I believe that this is an incorrect reading of events, for the following reasons.

- Caesar consistently rushed into risky ventures in a rash and reckless fashion and was the very last person to suffer from nerves or second thoughts on the brink of a great venture.

- It is evident from our sources that Caesar at the Rubicon was careful not to disclose to his companions any hint of his actual intentions beyond the immediate river crossing. He did not mention the imminent attempt on Ariminum and he said nothing of the advance party which he was sending forward. He avoided discussion of his plans by sticking to trite generalisations about the evils of civil war. This was consistent with his habitual attention to operational security.

- Talking in general terms about the dire consequences of proceeding across the river gave Caesar an ideal opportunity to gauge from the responses of his companions the true level of their commitment to his cause. There could be no better moment to distinguish the true enthusiasts from those starting to experience cold feet.

- The time spent stationary on the bank of the Rubicon in no way indicates indecisiveness and is a mark of a competently planned military operation. Caesar has assembled his attack forces at his chosen forming-up point with time in hand, and he will advance when appropriate and not before.

I do not for a moment believe that Caesar at the Rubicon was in any doubt about what to do. If he chose to advance at the sound of the famous trumpet blast (of which more below), it was because it occurred at his chosen time for moving off.

The Journey from Ravenna to the Rubicon

Suetonius has Caesar undertake a strangely improvised and chaotic journey from his base at Ravenna. Here is his account.

Dein post solis occasum mulis e proximo pistrino ad vehiculum iunctis occultissimum iter modico comitatu ingressus est; et cum luminibus extinctis decessisset via, diu errabundus tandem ad lucem duce reperto per angustissimos tramites pedibus evasit. (Suet. Div. Jul. 31)

And here again the conventional translation as given in Part I:

It was not until after sunset that he set out very privily with a small company, taking the mules from a bakeshop hard by and harnessing them to a carriage; and when his lights went out and he lost his way, he was astray for some time, but at last found a guide at dawn and got back to the road on foot by narrow by-paths. (Tr. J.C. Rolfe, Loeb, 1913)

And here now my own literal translation which makes this episode sound even less characteristic of Caesar the mighty commander.

Then after sunset, mules from a nearby bakery having been harnessed to a vehicle, he began a most secret journey with a small party; and when (the lights having gone out) the track almost petered out, he wandered for a long time. Finally, a guide to the light having been found, he escaped on foot through the narrowest paths.

Plutarch has picked up some version of the same story with his statement that Caesar

αὐτὸς δὲ τῶν μισθίων ζευγῶν ἐπιβὰς ἑνός ἤλαυνεν ἑτέραν τινὰ πρῶτον ὁδόν, εἶτα πρὸς τὸ Ἀρίμινον ἐπιστρέψας.

Mounted one of the hired carts and drove at first along another road, then turned towards Ariminum.

This comes just after Plutarch’s mention of Pollio by name, which perhaps signals that he is here using Pollio as a source.

By contrast Appian disregards the strange tale entirely and gives a brief and much less improbable account:

ζεύγους ἐπιβὰς ἤλαυνεν ἐς τὸ Ἀρίμινον, ἑπομένων οἱ τῶν ἱππέων ἐκ διαστήματος.

He (Caesar) mounted his chariot and drove towards Ariminum, his cavalry following at a short distance.

Suetonius’ account of Caesar’s journey is implausible. Caesar was supreme governor of the province, and commander of a vast army, and would not have needed to borrow mules from a bakery. And after nearly a decade of solid campaigning, Caesar and his staff officers would have known how to ensure that commanders did not get lost on the way to an important rendezvous.

It is sometimes said that Caesar’s unconventional travel arrangements were intended to disguise his movements. This idea seems misconceived. Any journey undertaken by Caesar in so eccentric a way would have been far more likely to attract than to avoid notice.

My explanation is that the story with the mules comes from the lost history by Pollio and that the relevant passage in Pollio must have read something like this:

Caesar had previously told a few friends to follow him by different routes, including Asinius Pollio. After sunset he harnessed mules from a nearby bakery to one of the hired carts and set off in secret. His lights went out, the track petered out and he wandered on foot until he finally found someone to guide him along narrow paths.

So Pollio, not Caesar, was the person who made such a mess of travelling to the Rubicon and Suetonius, ever attracted to the most colourful version of events, exploited a slight ambiguity in Pollio’s language to brighten his narrative by saying that it was Caesar rather than Pollio who suffered these embarrassments while en route to the Rubicon.

Caesar’s entourage at this time fell into two categories. Some were existing members of his military staff, while others had only just travelled from Rome to join him. It sounds as if Pollio fell into the latter category – a staff officer would not have lacked transport – and if Pollio travelled from Rome as a passenger in a friend’s carriage it is easy to see that when told by Caesar to travel on by himself he might very well have had to improvise transport at short notice in the way described.

Suetonius and the phantasmal trumpeter

This leaves the supernatural trumpeter originating in the account by Suetonius. On examination, it turns out that the supernatural aspects of the story are inventions of modern translators which are not supported by the original text. Here is the passage in question.

cunctanti ostentum tale factum est. quidam eximia magnitudine et forma in proximo sedens repente apparuit harundine canens; ad quem audiendum cum praeter pastores plurimi etiam ex stationibus milites concurrissent interque eos et aeneatores, rapta ab uno tuba prosilivit ad flumen et ingenti spiritu classicum exorsus pertendit ad alteram ripam. tunc Caesar: “eatur,” inquit, “quo deorum ostenta et inimicorum iniquitas vocat. iacta alea est,” inquit. (Suet. Div. Jul. 32)

Here is a well-known translation of this passage.

As he stood, in two minds, an apparition of superhuman size and beauty was seen sitting on the riverbank playing a reed pipe. A party of shepherds gathered round to listen, and, when some of Caesar’s men broke ranks to do the same, the apparition snatched a trumpet from one of them, ran down to the river, blew a thunderous blast, and crossed over. Caesar exclaimed, “Let us accept this as a sign from the gods and follow where they beckon, in vengeance on our double-dealing enemies. The die is cast.” (Tr Robert Graves 1957, Penguin Classics revised edition 2007)

Here is how several versions translate the phrase rendered by Graves as “an apparition of superhuman size and beauty” and (where a noun is used) the corresponding reference a couple of lines further on:

An apparition of superhuman size and beauty … the apparition … (Graves as above)

Un homme d’une taille et d’une beauté remarquables (a man of remarkable size and beauty) (French tr., M Baudement, Paris, 1845)

Ein Mensch von ungewöhnlicher Größe und Wohlgestalt (an unusually tall and well-built man) (German tr., Adolf Stahr, 1857)

A person remarkable for his noble mien and graceful aspect (tr. A. Thomson/T. Forester, 1909)

A being of wondrous stature and beauty … the apparition… (tr. J.C. Rolfe, Loeb, 1913)

A being of marvellous stature and beauty … the apparition … (tr. A.S. Kline, 2010)

A figure of remarkable size and beauty…the apparition … (tr. T. Holland, 2025)

Suetonius (unlike his translators) does not use any word equivalent to “apparition”. By my reading, he is scrupulous to avoid saying outright that the mystery figure was a supernatural entity, though he would not mind if his readers were left with that impression. The mentions of “apparition” or “being” in the translations are not justified by the corresponding word “quidam” in the original which just means “someone” or “a person”.

The talented musician, I suggest, was most likely a soldier indulging in a piece of high-spirited horseplay. A complete stranger running off with a signaller’s trumpet would have received short shrift.

I suggest that Suetonius has taken a straightforward anecdote, perhaps from Pollio, perhaps illustrating the high morale of Caesar’s men as they waited to advance, and recast it. He does so by stressing the fine physique of the musician, preceding the passage with a statement that Caesar was in two minds when “a prodigy” (ostentum) occurred and following it with Caesar mentioning a sign from the gods. As a consequence, many translators, aware of Suetonius’ fondness for the otherworldly and obedient to the hints he left behind, have devised their unearthly beings and apparitions. Though not all translators have gone for the wondrous apparition approach, the general impression has developed that the story of the Rubicon includes a supernatural trumpeter.

I argue that we should dismiss the supernatural apparition as a modern fiction. Perhaps Suetonius thought that so important event as the crossing of the Rubicon deserved to be marked by omens and portents. Finding nothing of the kind in his sources he then nudged the narrative as far in that direction as his authorial integrity would allow.

It is a relief to the modern reader to discover that Suetonius does not assert the presence of an apparition. To put it another way, he does not require us to believe in ghosts as a precondition of using his narrative as a historical source. But what about the signs and prodigies which Suetonius has Caesar detect? This is not a problem. We can comfortably accept as historical fact that a man blew a trumpet; we can equally accept as fact that Caesar and Suetonius elected to treat this event as a portent of the future, even though our own belief system may differ from theirs.

In the passage quoted above, Suetonius uses the word ostentum (a prodigy, wonder or portent). Throughout De Vita Caesarum he uses this word to describe events which are not necessarily supernatural by their nature but within which (from a Roman point of view) those who have eyes to see can discern foretellings of the future.

A good, solid, satisfying ostentum should be striking or unusual in some way. A set of gold dice thrown into a fountain at the behest of an oracle and there displaying the highest possible score will do nicely (Tib. 14), as will a stray dog dropping a human hand (symbol of authority) beneath a future emperor’s breakfast table (Vesp. 5). So it is not surprising that Suetonius has played up the physical stature of the trumpeter.

For reasons already made clear I do not believe that the trumpet episode persuaded a doubting Caesar to make up his mind to advance. The trumpet must have been blown at a time of night which Caesar had already selected as suitable for the start of his advance. Every aspect of Caesar’s behaviour during this operation, when closely examined, shows him as notably competent and professional.

Did Caesar truly refer to the trumpeting as an omen, one of the deorum ostenta? If so, did he really view the event in this way or was he just saying so out of convenience? That is impossible to say for sure, but whatever the truth of the matter it need not threaten our analysis of the course of events.

We can be confident that Caesar was not unduly at the mercy of portents. As Suetonius reports elsewhere,

To such a pitch of arrogance did he proceed, that when a soothsayer announced to him the unfavourable omen, that the entrails of a victim offered for sacrifice were without a heart, he said, “The entrails will be more favourable when I please; and it ought not to be regarded as a prodigy that a beast should be found wanting a heart.” (Div. Jul. 77)

Conclusion

So much for the apparent anomalies in the Rubicon story – Caesar’s uncharacteristic indecision, his improbable transport arrangements and the spurious supernatural trumpeter. At the end of this discussion, these need no longer detract from the historical credibility of the accounts which were examined in Part I of this article.

Robin Alington Maguire is a former civil engineer and banker with a longstanding interest in ancient history and culture. He likes to seek out new deductions from fragmentary ancient sources. He has translated and edited Napoleon Bonaparte’s Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar (Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2018). His earlier essays for Antigone argued that Cicero should have taken a different tack during the Catilinarian Conspiracy of 63 BC, reconstructed the rations supplied to the crews of Athenian trireme warships, delved into submarine springs of antiquity, and examined Greek and Roman catapult artillery.

Further Reading

The following articles offer a variety of perspectives on what happened at the Rubicon. Given the vast volume of writing about this crisis in history, it seems remarkable that more attention has not been paid to teasing out from the sources the detailed sequence of events during the crucial hours.

Anke Rondholz, “Crossing the Rubicon, a historiographical study,” Mnemosyne 62 (2009) 432–50.

Robert A. Tucker, “What actually happened at the Rubicon?,” Historia 37 (1988) 245–8.

Thomas P. Hillman, “Strategic reality and the movements of Caesar, January 49 BC,” Historia 37 (1988) 248–52.

Ronald T. Ridley, “Attacking the world with five cohorts: Caesar in January 49,” Ancient Society 4 (2004) 127–52.

G.R. Stanton, Why did Caesar cross the Rubicon?,” Historia 52 (2003) 67–94.

Tenney Frank, “Caesar at the Rubicon,” Classical Quarterly 1 (1907) 223–5.

Most of these articles are available at JSTOR.org, which offers free accounts that give liberal access to its contents without requiring any academic affiliation.