Morgan Kim

Rome and America

America is often compared to Rome: both are considered the most powerful nations of their day; both threw off the yoke of monarchical rule through revolution; both have, or had, operated a successful democratic republic for centuries. America, in fact, was indeed consciously modelled after Rome: Thomas Jefferson found his inspiration for the Declaration of Independence in Cicero, while Hamilton, Madison, and Jay wrote the Federalist Papers under the name ‘Publius’. The Fall of Rome been a favorite topic of modern-day American politicians – and fearmongers: is Washington D.C. about to face a similar fall?

Such parallels neglect one crucial fact: the Founding Fathers modelled the United States on the Roman Republic, not the Empire that fell in AD 476. Five centuries before the Roman Empire fell, the Republic ended in 27 BC with the ascendancy of the Emperor Augustus. Free citizens of Rome denounced the very idea of a king, or rex. They were proud of their forefathers who had expelled the state’s last king, Tarquinius Superbus, in 509 BC. No one living in the Republic could imagine another autocrat lording over them, until the day it happened. So just how did it happen?

Unsteady Foundations

A popular tribune being lynched by his fellow aristocrats in 133 BC was the first sign that things were going awry in the Republic. Tiberius Gracchus (163–133 BC) had attempted to pass an agrarian bill which would have redistributed land from the wealthy to the poor – or, to be more specific, agri publici (“public lands”) that had been illegally appropriated for private use by wealthy squatters. Knowing that these wealthy squatters in the Senate would obstruct the bill, Gracchus forewent their approval, flouting the mos maiorum,[1] and presented it directly to the Plebeian Council to be met with roaring approval. So a group of disgruntled senators bludgeoned Gracchus to death in public with wooden benches and any other object they could find.

Class struggle had always been an element of the Republic; plebeians wrested their right to hold public office from the patrician oligarchy through multiple secessiones plebis (“general strikes”) in which they withheld their labor by physically marching out of the city. Only after 200 years of patrician concessions and compromises did Rome achieve full political equality for all its citizens; even then, the bulk of the candidates for office ended up being sons of patricians or wealthy, well-established plebeians who had the names and funds to sway and buy their votes. Nevertheless, a relative equilibrium between the classes was maintained for 150 years after the fifth and last secessio (287 BC).

But in 146 BC, Rome defeated its last serious contender for Mediterranean supremacy, Carthage, in the Third (and last) Punic War (149–146 BC); an unprecedented influx of wealth poured into the empire from the spoils of victory. With the money, senators bought exotic fish for their countryside villas. Why, then, did the urban poor still roam the streets hungry? Gracchus’ death, as the culmination of this renewed class conflict, set the precedent for political violence that would dog the remaining days of the Republic.

This was only the beginning of the end. Corruption ran rampant in the government; officials saw fit to bleed their provinces dry to repay the loan sharks who funded their political campaigns; and of course they also filled their own coffers. One such official was Gaius Verres (114–43 BC), who appropriated Sicilians’ art collections for his own gain, as Cicero described in a famous series of prosecution speeches. On the other hand, candidates who failed in elections and had nothing to show for their efforts – except for campaign debts – sometimes turned to rebellion. The most famous example was Lucius Sergius Catilina (108–62 BC), who conspired with other also-rans in 63 BC to attempt mass arson, insurrection, and ultimately a coup on the city. While the attempt failed, it was an omen of political discord to come.

The Granting of Extraordinary Powers

Political strife notwithstanding, Rome went on to claim the ends of the known world. It conquered the whole of Italy, then Greece, then Asia Minor. Each glorious campaign tipped the scales of power away from civic statesmen to military strongmen. Because there was no official governmental body to grant soldiers pensions, veterans had to rely on their generals for money; thus they developed a sense of loyalty, less towards Rome as a whole than to their individual generals. For this reason, the leader of the Grecian campaign, Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138–78 BC), was able to return home, become dictator, and commence a massive purge of his political enemies via proscription. Pompey the Great (106–48 BC), in his Eastern command, settled boundaries and handed out kingdoms to foreign monarchs loyal to him (one of them being Antipater, father of the Biblical Herod) at his own will, with no need to consult the Senate about his decisions. In other words, he exercised almost king-like power.

While they were generals abroad, such men were indulged by the Senate, since they were expanding the glory and greatness (as well as the boundaries and coffers) of Rome. But when they returned home, they were expected to simply give up their power (in the form of disassembling the army before entering the bounds of Italy) and once again play nicely within the rules of the Republic, which banned excessive ambition – regal, tyrannical ambition. The term ambitio referred to a punishable crime in the Republic. Sulla of course broke with this tradition, but he did retire from his dictatorship after the proscription was over. Pompey the Great duly disbanded his army much to the Senate’s approval and relief – setting a virtuous example. However, the Senate would soon find out that not everyone could possess such civic virtue.

Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) had already attained his position as pontifex maximus before embarking on his Gallic campaign up north. Born to a noble family in decline, Caesar was determined to climb his way out of debt and up the cursus honorum to achieve supreme power. In this respect, he did not differ much from enterprising contemporaries such as Sergius Catilina; but unlike them, he was successful. He aligned himself with Rome’s two most powerful men at that time – the aforementioned Pompey, and Marcus Crassus (115–53 BC), the richest man in Rome. Through their funds, combined with his own political prowess, he secured himself governorship in the frontier of Gallia Narbonensis, the lone Roman province that stood beyond the bounds of the Alps at that time. There, during the eight-year course of his Gallic Wars, Caesar amassed for himself astronomical amounts of wealth, land, and a battle-hardened army that he retained at his disposal.

Factional divides had already ravaged the stability of the Republican government by the time Caesar consolidated all this power to himself. Rather than recognize the extreme fragility of the situation, the Senate (radicalized into conservatism by the reactionary Cato the Younger) tactlessly threatened Caesar with prosecution, on charges of regal ambitions, upon his return to Italy. He knew that as a private citizen without an army he would be helpless to resist his arrest and near-certain prosecution. Obviously Caesar refused to do this to himself. As a result, Cato pressured the Senate to declare war against Caesar. Soon afterwards, on 10 or 11 January 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his army. The first of the Republic’s civil wars began.

Civil Wars

Three civil wars in total followed that fateful crossing, in fact. The first was Caesar’s against the rest of the Senate, who were led by his erstwhile ally Pompey the Great. Pompey was decapitated in 48 BC by a former ally in Egypt, Cato disembowelled himself two years later in , and Caesar emerged the victor. The Senate (newly repopulated with Caesar’s own supporters) declared Caesar dictator perpetuo – dictator for perpetuity. The remainders of the old guard in the Senate, including Marcus Brutus (85–42 BC) and Gaius Cassius (86–42 BC), were alarmed by an unprecedented honor bestowed on him. Dictatorships, as an emergency measure, were meant to be held for six months at most; even Sulla, who held the position for three years, stepped down after his proscriptions were done. Fearing Caesar would become the Romans’ new tyrant, Brutus and Cassius formed a junto among like-minded liberatores and murdered Caesar in the now-famous Ides of March conspiracy.

Although Caesar was dead, Brutus and Cassius failed to stop the rise of tyranny. They failed to control public opinion, and lost the propaganda war to the Caesarian faction: Mark Antony, Caesar’s former second-in-command, seized upon a chance to give Caesar’s funeral oration and rile up the common people – who loved Caesar for his grain doles and public projects – against the conspirators, who fled to the Greek city of Philippi, where they were defeated in battle in 42 BC at at the hands of Antony’s forces, as well as those of the newest entry in the political arena, Caesar’s heir Gaius Octavian (63 BC–AD 14). Cassius committed suicide first, then Brutus followed. Eventually, Antony and Octavian waged one last civil war between themselves, in which Octavian, after a decisive rout of Antony’s forces in the Battle of Actium (2 September 31 BC) and Antony’s subsequent suicide, emerged as the most powerful man in Rome.

There was no second conspiracy to murder the second Caesar. By this time, the Senate was tired of fighting for democracy. Most of the traditional nobles had been wiped out by the three civil wars, and the remaining ones wanted to stay alive. Fortunately, this was not a problem, as Octavian – now styled Augustus, “the venerated one”– promised the Roman people a return to traditional virtues of the olden, golden days of the Republic.

Welcome to the Empire

That promise was a lie. If democracy and republicanism did not die when Caesar became dictator, they were certainly dead when Augustus became emperor. Although he used myriad synonyms – imperator (“leader”), princeps (“the foremost”), Augustus (“venerable”) – it was clear that this monarch was a king by any other name. Augustus passed a series of miscellaneous moral laws, collectively known as the Leges Iuliae, to mandate a return to quaintly traditional mores. He mandated marriage, criminalized adultery, and promoted procreation. The wanton liberality that had characterized the Republic (Sulla was famous for his orgies, Caesar for his adulteries) gave way to constraint and order in Augustus’ Empire.

Gone too was the Republic’s freedom of speech: whereas Catullus was free to pen libelous verses about Caesar’s (rumored) sexual deviancies, Ovid was banished for his carmen et error, “a verse and a mistake” (Tristia 2.207). The precise cause of Ovid’s exile is now obscure, but his poem the Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) is a possible candidate, since it potentially corrupted the youth by giving them seduction advice. Roman literature from Augustus onwards followed an established line of orthodoxy.

In his Res Gestae, Augustus claims rem publicam… in libertatem vindicavi – that he ‘restored liberty to the Republic’ (Res Gestae 1.1). Virgil, effectively his official poet, sings praises of the divi genus (‘descendant of the Deified’) and his aurea saecula (‘Golden Age’) in the Aeneid (Aen. 6.792–3). The vulgar yet candid tone of much Republican literature was replaced by something more straight-laced and obsequious.

What Rome Traded Away

When the bulk of Augustus’ titles were transferred to his stepson and designated heir, the Emperor Tiberius (42 BC–AD 37, r. 14–37), after his death, no one protested what should have been a suspiciously monarchical-looking succession. The nobility were grateful enough to hold on to what remained of their wealth, influence, and lives, while the public found themselves satisfied with their fill of panem et circenses: doles of grain were cheaper than ever before under the new administration, and public entertainment was free on government-funded arenas and racetracks. In return, the quondam ‘citizens’, who were in the process of becoming imperial subjects traded away their key rights – most importantly, their freedom of speech.

Cicero called the Republic “Romulus’ cesspool”, Romuli faex (Ad Att. 2.1.6), but he was nevertheless free to call it that. Centuries later, John Milton in Paradise Lost would allude to a “free Rome, where Eloquence / Flourished, since mute” (PL 8.671–2). The golden age of Latin oratory died with the Republic, when Cicero’s head and hands were nailed to the Rostra (7 January 43 BC) by Antony for daring to speak and write against a triumvir; in literary terms, the age of the Empire yielded mostly panegyrics about the emperor.

The Romans also lost their vote. While moral deviants such as Caligula (AD 12–41) and Nero (AD 37–68) inherited and abused their power, the Roman people lacked the ability to vote them out of office or prosecute them for their criminal charges after their terms were finished, for there was no end to these Emperors’ terms – not, at least, until their deaths by political assassination or suicide. The deprivation of power from an undeserving holder lost a peaceable avenue of pursuit.

These two losses might have paled in comparison with the newfound peace and stability that the Empire promised – the Pax Romana – as well as the expansion of its territories. And for the centuries that followed, the people living under the myriad monarchies that followed the fall of Western Rome in AD 476 had taken kings’ claims to divine right as granted, as the natural order of things. It was only in 1776 – 1,800 years after Augustus became emperor in 27 BC – with the founding of the United States that democracy once again became a mainstay of the world. The French followed, then the rest of the West.

Democracy is our standard today. But for how much longer? The fall of the Roman Republic was no overnight process, but it took Octavian a mere seventeen years, between 44 and 27 BC, to crown himself Augustus. In truth, although the Republic’s end was not unexpected, it was also not inevitable. Factional, internecine in-fighting and corruption let the Republic rot and collapse from within, not any foreign invasion; civil wars ravaged the country and its people, not the Carthaginians nor the Gauls; and it was to a fellow Roman that the rest of Rome had surrendered their liberty and dignity, not some foreign occupier.

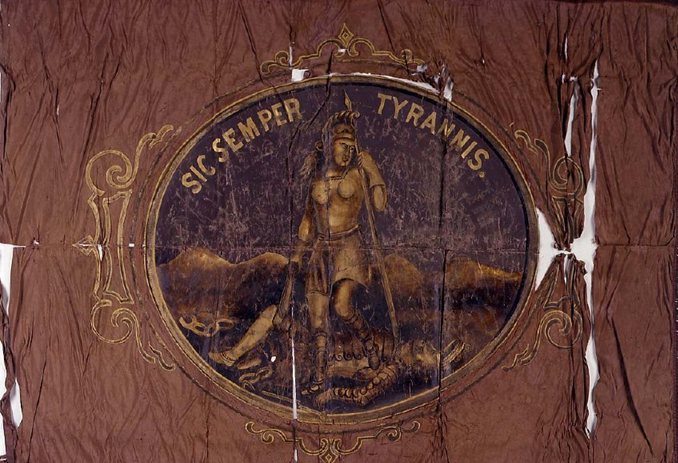

History is cyclical, but need not be a full circle. We do not need to watch democracy fall less than 300 years after it was reborn, and wait another 1,800 years for it to be found again – nor should we. Αs the citizens of a democratic republic today, it’s our right and our duty to protect our own democracy from falling to the hands of a tyrant. As Brutus said, and Virginia’s state motto goes: sic semper tyrannis.

Seoyoon (Morgan) Kim is a junior at Memorial High School in Houston, Texas, where she is the head of the Classics Club. Her favorite author is Cicero. She finds especially fascinating the connection between the Roman Republic and the early American Republic.

Further Reading

Anthony Everitt, Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Emperor (Random House, New York, 2006).

Anthony Everitt, Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician (Random House, New York, 2001).

Notes

| ⇧1 | The mos maiorum (“the custom of the ancestors”) was a set of unwritten social rules that acted as Rome’s informal constitution. |

|---|