Michael Fontaine

Julius Caesar killed a million human beings during his campaigns in Gaul (58–50 BC). He enslaved a million more. Or so he boasted, anyway. Even if those numbers are implausibly high, they’re still shocking. Why did he do it?

Wars of conquest are out of fashion, so they’re never easy to explain to students. Luckily, Caesar himself wrote his own Commentarii. We have them and can read them for ourselves. Of course, that doesn’t make them honest or true. But Caesar’s own words do help us understand his stated justification and reasoning, which were meant as much for his contemporaries back in Rome as they were for posterity.

At the same time, reading Caesar’s commentaries on The War for Gaul or The Civil War today poses challenges. The names can be unfamiliar, even daunting. Who are all these tribes, rivers, and provinces? Where are they today? What on earth are the Allobroges, or where is Narbo? How much was a sestertius worth back then – or now? It takes a lot of flipping through commentaries of a different kind just to get started.

All of this is preface to an extraordinary new text I recently got my hands on: The Collected Speeches of Vladimir Putin – in Latin. I’ve been looking for it for seven years.

Yes, you read that right. Vladimiri Putini Vladimiri F(ilii) Orationes Selectae in Latinum Versae (“Selected Speeches of Vladimir Putin, son of Vladimir, Translated into Latin”) was published in Moscow in 2016. If that sounds like a spoof or satire, I assure you it’s not. I didn’t concoct this as a prank (I’ve been accused of that before!). The book is real.

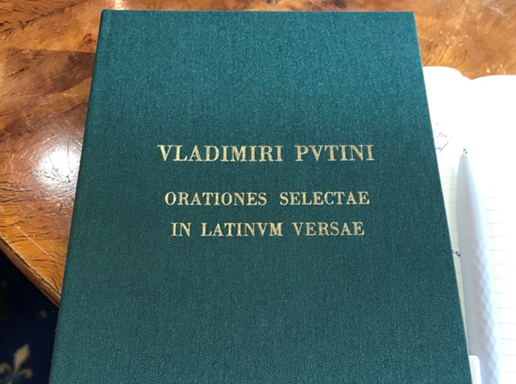

The story of how this Latin Putin appeared is almost as bizarre as the book itself. Back in 2018, Moscow-based journalist Max Seddon posted a curious photo on Twitter. “Spotted at a Moscow interview: the collected speeches of Vladimirus Putinus in Latin,” he wrote. The attached image (which quickly made the rounds among amused Classicists on Reddit and Twitter) showed a book with a handsome green cover, Putin’s name grandly stamped in gold foil Latinized capitals.

Naturally, I was intrigued (that’s putting it mildly). Where had this book come from? Who took the time to translate Putin’s orations into Classical Latin? And most importantly, how could I get a copy? I reached out to Seddon and others for leads. Seddon replied, but, alas, couldn’t source me a copy. Nor could anyone else I pestered.

For a while it seemed like this odd volume would remain a phantom – something you know exists but can’t get hold of. That’s happened with Latin books before too. But then, after several years of searching, a breakthrough: at some point recently, an anonymous blog post leaked a PDF of the entire book. It popped up on an Italian-language site for Latin enthusiasts, with no commentary – just the file.

The Soviet era may be over, but it seems the samizdat tradition carries on in Russia. I downloaded it immediately, hardly believing my luck. Truly a gift from the bibliophile ether!

When I opened the PDF, I found myself staring at a surreal sight. The text begins with a frontispiece: an unsigned portrait of Vladimir Putin himself, rendered in elegant grayscale shading. It gives the impression of a Classical statesman from some bygone era – except, of course, the statesman is very recognizably the 21st-century Russian president.

The book contains two speeches by Putin, translated into polished Latin prose. The first is his lengthy speech delivered at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, a famous address in which Putin challenged the idea of a “unipolar” world dominated by the US. (For context, this was a bold speech at a Western forum, laying out Russia’s grievances with NATO expansion and American foreign policy.) The second is his shorter March 2014 address to the Federal Assembly (Russia’s parliament) regarding the status of Crimea, given just after Russia had invaded and annexed Crimea.

Both speeches are significant in understanding Putin’s worldview. More importantly, because Russia went on to invade Ukraine in 2022, these two speeches – which in 2018 seemed merely a curiosity – have assumed far greater relevance. They offer insight into (or at least propaganda justifying) Russia’s actions in Ukraine. Because although Putin is Russia’s President, not its tsar, it does feel like shades of Caesar all over again.

Now, let’s be clear about one thing: reading this Latin text is not an endorsement of its politics; my interest lies in the Latinity. Both speeches have long been available in English (official Kremlin translations are on the web here and here), so there’s nothing secret in their content. The fascination is all in how they’ve been rendered into the language of Cicero and Caesar.

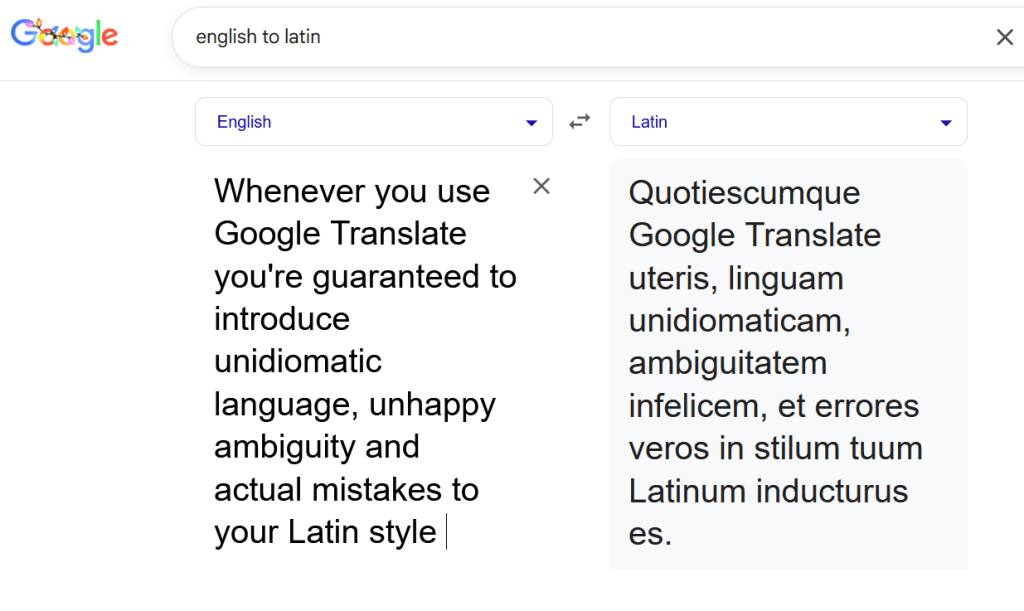

And rendered they are – with remarkable skill. Perhaps the most surprising thing about Orationes Selectae is that the Latin translation is absolutely first-rate. This isn’t a gimmicky Google Translate job, nor a lazy trot that merely swaps Russian words for Latin equivalents.

The unknown translator (or translators) have produced Latin prose that reads as if it could be an authentic work of the ancient world. Many renderings are ingeniously idiomatic – so much so that I often paused in admiration (and occasional amusement) at the phrasing. It’s surreal to see contemporary geopolitical rhetoric flowing in Classical Latin periods, yet it works shockingly well.

For example, in the 2007 Munich speech, Putin says:

This global stand-off pushed the sharpest economic and social problems to the margins of the international community’s and the world’s agenda. And, just like any war, the Cold War left us with live ammunition, figuratively speaking. I am referring to ideological stereotypes, double standards and other typical aspects of Cold War bloc thinking.

How on earth can these concepts and phrases be rendered in Latin? Here is what the book has:

Quae rerum omnium aequilibritas gravissima plerumque incommoda rei pecuniariae vitaeque socialis longe pepulerat ac velut exturbaverat e provincia rerum, quae omnium gentium coetui humanoque generi superessent agendae. Quod autem solet post bella fieri, nobis, bello — ut aiunt — frigido semel confecto, arma telaque quodam modo sunt relicta. Quid istuc verbi est? Doctrinas dico solidatas, pondera iniqua aliaque id genus quae solebant quo tempore bellum frigidum ducebatur cogitari.

In more literal translationese, this says:

This equilibrium of all things had driven the generally gravest disasters within financial affairs and social life far off, and all but thrust them from the domain of things that remained for the congress of all nations and for humankind to accomplish. Moreover, as typically happens after wars, arms and spears were somehow left behind to us after the so-called Cold War had been finished off for good. “What does that mean?” I am talking about hardened doctrines, unfair burdens, and other things of that sort which used to be contemplated while the Cold War was going on.

If you compare the two, you’ll see the translator really gets to the heart of the matter. In fact, because Latin lacks the weasel words that cloud modern diplomacy, the Latin may be clearer than the English. “Ideological stereotypes” become doctrinae solidatae, “hardened doctrines,” and “double standards” becomes pondera iniqua, “unfair burdens” or “weights” with iniquus adding a hint of “harm.” Elsewhere the translator even slips in Classical metaphors, having Putin speak of an “Iliad of troubles” in discussing the militarization of outer space. The style is strong throughout.

Putin’s 2014 speech – on Russia’s annexation of Crimea – is of even greater immediacy. In it Putin lambasts what he calls the corrupt post-Soviet leadership in Ukraine for impoverishing the country. The official English translation from the Kremlin goes:

They milked the country, fought among themselves for power, assets and cash flows and did not care much about the ordinary people. They did not wonder why it was that millions of Ukrainian citizens saw no prospects at home and went to other countries to work as day labourers. I would like to stress this: it was not some Silicon Valley they fled to, but to become day labourers.

The Latin rendition is impressively vivid and idiomatic:

Civitatis ubera – ut ita dicamus – siccarunt, de potestate, de bonis, de pecunia inter se certando, homines neglexerunt communes, nihil mirati quaenam esset causa, cur paene innumerabiles cives, spem domi prospicientes nullam, emigrare cogerentur, peregre sibi ut quaestum victumque pararent in diem mercenarii famulantes. Id maxime urgere aveo: homines illos non quandam Siliconiam Vallem petituros emigrasse, verum se contulisse illuc, ubi in diem mercenarii dominis famularentur.

Even Putin’s more incendiary lines come across powerfully in Latin. In the same speech he claimed that the 2014 Maidan revolution – described by critics as a violent overthrow and by supporters as a popular uprising – was the work of unsavory radicals: “Nationalists, neo-Nazis, Russophobes and anti-Semites executed this coup. They continue to set the tone in Ukraine to this day.” The Latin version delivers this with Ciceronian scorn:

Viri suae nationis paene fanatici, nazismi fautores recentes, Russorum timidi, osores Iudaeorum id egerunt hodieque in Ucraina tenore eodem consiliorum obstinati perseverant.

It’s easy to imagine Cicero himself lambasting Catiline’s allies with such phrases.

Beyond the novelty factor and the linguistic craftsmanship, one question lingers: What is the pedagogical or cultural value of reading Vladimir Putin in Latin?

The answer, I think, circles back to the challenges of ancient texts I mentioned earlier. When students read Classical accounts of the Jugurthine or Peloponnesian War, they struggle with unfamiliar context – dozens of names of minor kings and regions, ancient monetary units, archaic social structures. In Putini Orationes, the reference points are much clearer. They know who George W. Bush is when he’s mentioned as Georgius W. Bush, Americanorum rei publicae moderator (America’s head of state). We all have a mental image for Ukraine or Silicon Valley.

Putini Orationes should also have the reverse effect. If you reread Caesar’s Commentaries after this book, his writings may suddenly leap forward 2,000 years. You’ll gain a greater appreciation of the social and political dynamics he’s describing in deceptively simple Latin.

Why was Latin – a language we don’t typically associate with Russia – chosen for this project? One might have expected Russian leaders to promote Church Slavonic or even Ancient Greek for a pseudo-biblical gravitas. But Latin? The answer is surely the obvious one: to cast Putin’s words in the venerable tongue of Old Rome, the language of Caesars and Popes, giving them a timeless, “universal” quality. Because, even today, there are some who style Moscow the “third Rome”.

So who did it, and why? Unfortunately, the book itself provides few clues. There are no credited translators, no introduction, and no commentary – just the Latin speeches printed cleanly on the page. The only hint comes at the very end in a Latin colophon:

This cryptic note seems to refer to the Society for the Promotion of Russian Historical Development “Tsargrad,” a pro-Kremlin, neo-monarchist organization in Russia. The group, led by oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, is known for championing Russian Orthodox heritage (and, less flatteringly, for spreading disinformation).

“Tsargrad” (Caesar City) is the old Slavic name for Constantinople, seat of the Orthodox Christian empire, so there’s a heavy dose of historical mystique in that name. In any case, the Tsargrad Society’s involvement suggests this Latin opus had an ideological motive: casting modern Russia’s narrative in the dignified cloak of Roman-style discourse.

You probably won’t find Putini Orationes for sale at your local Barnes & Noble anytime soon. But here’s a copy. Get it while you can…

Mike Fontaine is Professor of Classics at Cornell University and Director of Cornell’s Program on Freedom and Free Societies. His latest book is How to Have Willpower: An Ancient Guide to Not Giving In. He has previously written for Antigone about Ciceronian forgeries and Roman Algeria.

Further Reading

For excellent analysis of Caesar’s Commentaries, I recommend Luca Grillo & Christopher B. Krebs (edd.), The Cambridge Companion to the Writings of Julius Caesar (Cambridge UP, 2018), especially the chapters by Grillo and Krebs themselves, as well as James J. O’Donnell’s superb 2019 translation, The War for Gaul (Princeton UP, 2019).

On Moscow as the Third Rome – Constantinople/Istanbul being the Second Rome – see Nick Mayhew’s 2021 summary here.

Those who love hunting for literary rarities will love Georges Minois’ book The Atheist’s Bible: The Most Dangerous Book That Never Existed (Univ. of Chicago Press, IL, 2012).