J.S. Blackie

What follows is a groundbreaking lecture on the study of Ancient and Modern Greek. Although delivered in the mid-19th-century, only in recent years has its core contention started to find support: that students learning Ancient Greek around the world should take Modern Greek seriously as the linear development of that language. What living language can show so little change over three millennia on human lips? Furthermore, Ancient Greek should be spoken in the classroom and lecture hall, whatever the particular pronunciation, and this is most easily done by treating Modern Greek as the entrance point into its live form.

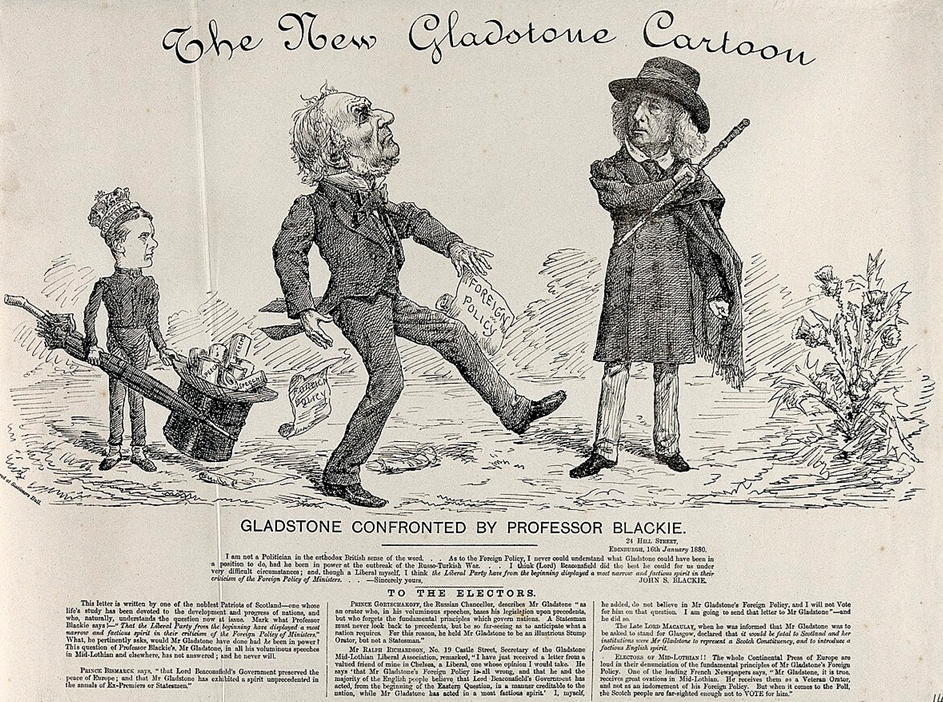

The lecture was delivered by the remarkable scholar John Stuart Blackie (1809–95), who served as Professor of Greek at Edinburgh for three decades (1852–82) and rose to a position of national prominence as a public intellectual. Unusually for British Classical scholars of the era, his education involved time in Göttingen and Berlin, where the discipline was developing along broader and more ambitious lines. Travel in Italy, and especially Greece, infused Blackie with a more well-rounded and vital enthusiasm for the spirit of antiquity; it also led him to see contemporary Greeks as the proud conduits of a linguistic treasure (Modern Greek, which he terms “Romaic”) that had never left their possession.

Although Blackie’s contributions to scholarship and culture were significant, he did not succeed in his mission of propagating the teaching of Greek by the spoken method. His attempts to reform the pronunciation of Greek in the British Isles, set out in a pamphlet of 1852, did not catch on. Despite his touring England to promote these contentions, he came home disappointed. After his last Oxford lecture, in 1893, he confided: “It is utterly in vain here to talk reasonably in the matter of Latin or Greek pronunciation: they are case-hardened in ignorance, prejudice and pedantry.” However, now in 2025 several institutions, in Europe and America, are committed to reuniting Ancient and Modern Greek, and bringing the Classics to life again viva voce, following Blackie’s inspiring lead.

On the Living Language of the Greeks

and Its Utility to the Classical Scholar

An Introductory Lecture

Delivered in the University of Edinburgh

At the Opening of Session 1853–4

John Stuart Blackie F.R.S.E.

Professor of Greek

The language spoken by that most notable branch of the human family, called by Europeans GREEKS, and by themselves HELLENES, having become an object of general study in Europe, not for the sake of holding living intercourse with that people (as we learn French to speak with Frenchmen), but altogether on account of the rich literary and scientific inheritance which they have transmitted to us from ancient times;—it will strike no one as surprising, that of the hundreds of famous philologists that have occupied themselves with the language of the Greeks, from the days of the Italian Medici till now, hardly one, or only one in a thousand, has thought it worth while to cast even a passing glance on the living Greek dialect, as spoken in these modern times by the descendants of Homer and Pericles. While the spoken language, it was universally imagined, might be useful to a young merchant wishing to push his fortune in Leghorn, Trieste, or Smyrna, the accomplished philologist or theologian, it was conceived, would most naturally find the weapons of his learned warfare in those gray and time-crusted libraries that he had chosen for his battle-field.

But this notion, however convenient for bookish men, was shallow and unphilosophical; it being a known fact, that nothing in nature is more tenacious of life than language, and that so long as a people lives, in however degraded a state of literary culture, it preserves in its own bosom some of the purest fountains and most curious sources of its own philology. Nor is it at all certain that our great Greek scholars in England and Germany, ever distinctly proposed to themselves the systematic neglect of the living language of the Greeks from any such superficial views of philologic science; it would seem rather that accidental political circumstances contemporary with the revival of literature in the West, were the main cause of the neglect with which modern Greek has generally been treated by academical men. The Turkish empire, now so frail and crazy, and kept together less by its own cohesive strength, than by a formidable framework of foreign diplomacy, was, in the year 1453, and for a long time afterwards, regarded by Europe as an invading and disturbing power, against which the Christian states had much ado to maintain themselves in their relative positions.

Such a condition of things in the political world acted, of course, as a complete barrier against all intercourse between the learned Hellenists of the West, and the Christian Greek people, now confounded with their Mahometan conquerors; while, at the same time, this people, as the natural consequence of the condition of social serfage to which they were reduced, fell gradually into a state of literary wildness and desolation, compared with which the dry gardens of Byzantine pedantry seemed a Paradise. In this dreary condition matters continued till towards the end of the last century, when the general stirring of dry bones which the French Revolution caused, was felt also by the Christian subjects, of the Porte, and chiefly by the Greeks, who, with the memory of Marathon in their blood, had never ceased to hope that the freedom which their immortal fathers had lost, it might one day be theirs, as not altogether unworthy children, to claim. Previously to this period a Bentley, or a Hemsterhuys, or a Dawes, might well have been pardoned, if they thought that it was almost as vain to seek for Greek amongst the Greeks, as for Roman amongst the Italians; but after this period a marked and decided change took place in the intellectual condition of the Greek people, of which the philologists were bound to have taken notice.

Such, however, is the power of habit, especially in England, the grand European stronghold of all reasonable and unreasonable conservatism, that, though it is now more than half a century since Righas sounded his stirring Greek odes from Vienna, and Corais stood forth in Paris as the public representative of a restored scientific philology among the Greeks, nevertheless the old bookish conceit reigns everywhere undisturbed, and the existing Greek dialect is as thoroughly ignored by the generality of philologists in this country, as if the speech of the Hellenes had been swept from the living world, with the mystic records of the Brahmins, and the rubrics of old Etruscan diviners. This is the more remarkable, as, since the successful result of the glorious Greek revolution of 1821, the Greek language has put forth such a rich growth of bright green leafage, and shewn such a depth of uncorrupted vitality, that even a casual observer must have been struck with the phenomenon; while, with the decay of the Turkish power, generally, and the substitution of the cross for the crescent in the banners that float over the chaste ruins of the Parthenon, the grand wall of partition has been removed, that so long severed the Greek people from the sympathies of their Christian brethren in the West.

And the fact is, that these prosperous circumstances have in some parts of Europe already restored in some degree that connexion of academical scholarship with the living Greeks, which the unfortunate events that we have mentioned had dissolved; of this, the names of Professor Thiersch of Munich, and Professor Ross of Halle, may stand as a sufficient proof. But in Scotland I have scarcely met with a single person, learned or unlearned, on whose ear the assertion that Greek is a living—not a dead language, did not fall with the strangeness of a new truth; while in England, though there are, no doubt, several learned persons well acquainted with the true character of the existing Greek tongue, the general conservative habits of the scholastic profession, and the attachment of the Universities to a narrow and pedantic routine, have hitherto confined the Greek studies of the youth to the dead treasures of grammar and lexicon.

Another obstacle has had a most pernicious effect in keeping down the avenues of intercourse between the students of dead Greek books, and the speakers of the living Greek language—and this not in England only and in Scotland, but to a considerable extent also in Germany. After what I have already written on this subject,[1] I need scarcely say that I mean here that capricious and arbitrary method of pronouncing the Greek language, destitute alike of authority and of character, which, under the sanction of the great name of Erasmus, has hitherto prevailed in our British schools and colleges. The effect of this vicious habit has necessarily been to cut short all attempts at oral communication between English classical scholars in Greece, and the Greek people in Greece; so that, even in this age of railroads and steamboats, when Englishmen, systematically drilled in the classics, are continually coming in contact with Greeks in all parts of the world, it is among the rarest things to find one of our nation who, after a dozen years of profound study of the Greek language, is able to hold a single minute’s conversation with the people who speak it. Against the continuation of this lamentable state of matters, it is the object of the present lecture to enter a public protest.

Some years ago, having procured from a foreign bookseller in London certain books published within the last thirty years at Athens, I instantly perceived the very great injury inflicted on Greek scholarship by the habitual neglect of those living stores of the language, which, however inferior in classical value to the great works of the ancients, are, as an instrument of linguistic training, for obvious reasons, to us modems far superior; and in order to satisfy myself as to the existing state of the Greek language in the most direct way, I determined to seize the earliest possible opportunity of visiting the capital of the new kingdom of the Greeks, and residing there for such a period as would enable me to put forth a trustworthy judgment on the subject. From that visit I am now returned; and that judgment I am about to place before you. I lay before you also a list of modern Greek books, some of which I purchased in Athens, for the use of the University of Edinburgh, and some of which belong to my own private library.[2] From these materials all who are willing may now form for themselves a correct judgment with regard to the actual state of that famous living language, which so many of us were ignorantly allowed to look upon as dead; and as the consequence of this correct appreciation of the true linguistic position of the Greek scholar, I have not the least hesitation in predicting either that the Scottish people will prove themselves to care nothing for Greek but the name, and are blind to the most elemental philosophy of education, or that the method of teaching the Greek language in this country will speedily undergo a most important reform, and that for one bad Greek scholar raised under the old system, we shall have ten good ones under the new. I am speaking of what I understand thoroughly, not as an idle speculator, but as a practical man; and as such, I request you, as practical men, to lend your most serious attention for half an hour to what I shall now say.

In the first place, I have to assert as a philological fact, that there is not the slightest foundation for the notion commonly entertained, that the language now spoken by educated Greeks is a different language from the spoken in the days of Pericles and Demosthenes, in the same sense that the language now spoken by Mazzini is a different language from that spoken nineteen hundred years ago by Julius Caesar. Italian contrasted with Latin is, in every sense of the word, popular and scientific, a new language; Romaic is not. It were no doubt one of the most difficult tasks in philology, to attempt by strict definition to lay down the exact boundary line between a mere dialect variety of a language, as Doric is of Greek, and an entire new species, as Dutch, Danish, and Swedish are distinct species of the great Teutonic genus of human speech; just as naturalists are above all things puzzled to determine whether certain growths belong to the vegetable or to the animal kingdom. But as notwithstanding these curious ambiguities, the two great regions of animal life, on the one hand, and vegetable on the other, stand out with such a distinct prominence, that no sane man ever raises a question whether a lily may not perhaps be a beast, and a leopard a plant; so I am ready to prove to you practically, without any scientific puzzling for the present, that, while Italian is manifestly a new composite organism of human speech, both in its form and in its material, specifically different from its main parent the Latin, Romaic or Neo-Hellenic, as it is more properly called, bears on its face the stamp of a mere dialectic variety of ancient Greek, differing not more from the language of Xenophon than Attic prose generally differs from the dialect of Herodotus or Theocritus.

The proof of this is of the simplest nature possible. Take the following lines from the first canto of the Inferno of Dante, the great poet, who, as you know, first impressed the stamp of classicality on the new linguistical concrete which the strange fermentations of centuries had crystallized out of the language of ancient Rome:—

Che questa bestia per la qual tu gride

Non lascia altrui passar per la sua via,

Ma tanto lo ‘mpedisce che l’uccide;

Ed ha natura si malvagia e ria,

Che mai non empie la bramosa voglia,

E dopo‘l pasto ha piu fame, che pria.

I have not taken this passage at random, because, in a composite language, such as Italian or English, one may readily stumble on a passage that does not at all present the genuine character of the tongue, as a pure Saxon passage, for instance, in English, or a pure Latin passage in Italian; but these six lines contain, to the best of my judgment, a fair specimen of the language of the Italians, with the different elements of which it is composed in their just proportions. Now what do we find? Of the 46 words of which this passage is composed, only 9 have retained their Latin form so unaltered, that they must be immediately recognised by the most superficial Latin scholar, viz., bestia, per, tu, non, sua, via, tanto, natura, fame, and of these nine only three, bestia, tu, non, of which one is indeclinable, appears in the just grammatical form that belongs to it, according to the common laws of Latin grammar; the others are all employed either with a different meaning, or in a wrong case. Of the remaining words, three, viz., gride, lascia, bramosa, whatever their pedigree be (which we shall not discuss just now), certainly do not exhibit any Roman character or relationship even to a well-exercised philologic eye, while all the rest are Latin, but so transmuted and transmogrified, that a fair scholar might well be forgiven, if he should not at first recognise their character without the help of a dictionary.

Compare now with this result a similar analysis of the following passage from an Athenian newspaper (the Αθήνα, 7th September 1853,) which I have chosen as a fair specimen of the language, written and spoken at Athens by all educated men; for as to the dialect of Athenian street porters and boatmen of the Piraeus, I presume that neither now, nor in the time of Aristophanes, could it be produced as a just sample of Attic eloquence:

Ἀγγλική τις ἑταιρία προτείνει νὰ κατασκευάσῃ τηλέγραφον ὑποβρύχιον μεταξὺ τῶν Ἰονίων νήσων καὶ μιᾶς ἄκρας τῶν αὐστριακῶν ἀκτῶν. Ἤδη ἡ πρότασις καθυπεβλήθη είς τὸ αὐστριακὸν ὑπουργεῖον. Ὅταν αὐτὸς ὁ τηλέγραφος συστηθῇ, αἱ εἰδήσεις τῆς Ἀναταλῆς θέλουσι καταφθάνει εἰς Τεργέστην δύο ἡμέρας ταχύτερον παρὰ σήμερον.[3]

Now, the first distinctive characteristic that strikes us here is, that there is not a single word in the passage that is not pure Greek; in other words, that so far as the material is concerned, modern Greek is no mongrel composite of old Hellenic and new barbarian elements, but Greek as pure and unspotted as ever Homer sung or Aristotle penned. The change that has passed upon this remarkable language by the strange operations of disturbing centuries, is in fact, as Tricoupi, in the introduction to his admirable history, remarks, the least possible. Those foreign elements which, in the case of the old Roman language, were incorporated and worked up into a new whole, attached themselves with a loose coherence to the mere outward cuticle of the Hellenic, and, after sticking there like burs on a fair coat for a season, were driven, on the first convenient occasion, by the strong breeze of regenerated nationality, into the mire.

But you will ask, in what then does the difference between modern Greek and ancient Greek consist? The passage submitted to your analysis supplies the answer. You find several pure Greek words used, with a slight modification of meaning, from that common in ancient Attic Greek; not, therefore, however, in anywise the less Greek or the less ancient; because Athens had at no time the same exclusively dominant power over the norm of the Greek language that Paris has over the French; and after the conquest of Attica by the Macedonians, Alexandria, Byzantium, and other famous Greek cities, claimed and exercised the right of stamping on the common dialect their peculiar impress.

We observe, also, in the passage quoted, two peculiar constructions, which indicate not merely a change in the use of Greek words, but a loss of a remarkable kind in the power of verbal flexion;—a loss, however, which of all languages the Greek could most easily bear, as it was originally so exuberant in this department, that even in the age of the New Testament some of its verbal forms seem to have been tacitly dropt. I allude particularly to the optative mood, which, in the narrative portion of the New Testament, is generally supplied by the subjunctive of the first aorist, and, in the language of the modern Greek writers, always. In the New Testament, also, we find a frequent, though by no means a universal use of the conjunction ἵνα, that, in places where the classical Greek writers of antiquity would certainly have used the infinitive mood; and it is a most remarkable fact, as indicating a very close connexion between the New Testament style and Romaic, that this exceptive use of the subjunctive mood in the Greek of ancient Palestine, has, in the Greek of modern Athens, become the rule—to such a degree, that for all practical purposes the infinitive mood in Neo-Hellenic may be said not to exist. Of this we have examples in the passage quoted—προτείνει νὰ κατασκευάσῃ—the νὰ being a shortened form of ἵνα, as the scholar will readily discern.

Another equally remarkable loss which the Greek language has suffered in the course of time, is that of the future tense, for which, in this passage, as will be observed, the auxiliary verb θέλω is used—a usage, however, which the modern Greeks are as much entitled to adopt as the ancients were to use μέλλω, and various parts of the verb εἰμὶ, to be. I must observe, however, that Tricoupi, one of the best writers in the modern language, never uses θέλω in this sense, but only its contracted form θὰ, and in such a way as to be often an exact counterpart to the use of ἂν in the classical writers. It appears, therefore, as the result of our examination, that of all European languages, Greek is that which has maintained itself for the longest period with the least amount of change;[4] and that the graceful robe which was the drapery of Plato’s thoughts, still remains in all its bright splendour to his sons; the few base spots with which mediaeval rust had infected it, having been chemically washed out, and only one or two pretty points of superfluous lace torn away.[5]

I shall now make some remarks on the motives for studying the living Greek language, which ought to influence the mind of a classical scholar. And here it is natural, in the first place, to observe, that the mere continued existence of this remarkable tongue from the oldest Pelasgic times down to the present hour, that is to say, for fully 3000 years, is a fact so singular in the fluctuating history of dialects and peoples, that the complete philologist cannot willingly overlook it. As when one has spent the happy years of childhood on the green banks, and amid the woody cliffs of some beautiful river, and has followed up many of its tributary torrents, through far-winding glens to the foaming cascade, or the clear moss-grown well where they have their source—as this native of some fair Wharfe or Tweed, loves not only the spot where he was born, and the dark-brown swirling pool where he caught his first trout, but the whole course of the stream; and will trace with delight its whole progress through dreary sands and muddy Deltas, till it loses itself in the sea; so the student of any favourite language will not feed only on a few chosen authors, but follow out the whole stream of the national existence which it exhibits, and chronicle every point of its mazy wanderings with the pious faithfulness of an old monk. A feeling of this kind, I should think, will, with ingenuous youth, prove sufficient to excite an inquiring sympathy after the literary fate of those who still use the language of Demosthenes; but for brains of sterner stuff, I may remark, in the second place, that the living Greek language, though modern in name and organism, is, beyond all question, ancient in the greater part of its materials—more ancient, unquestionably, than that Attic form of the Hellenic tongue, which gives its colour to by far the more important part of the ancient Greek literature which we possess.

The student of Romaic, therefore, is not learning merely the most recent form of the language of Homer, but he is learning in part also a form of that language more ancient than Homer himself, and a form, of course, which the most exclusive devotee of things ancient is not entitled to look on as foreign to the narrow range of his peculiar speculation. It is a fact, for instance, patent on the very surface of the existing language, that the popular form of the third person plural present indicative λέγουν, Latin legunt, Doric λέγοντι, is a more ancient form than the common Attic λέγουσι. The full broad vocality of the old Doric is equally striking in the terminational syllable of such words as ψωμᾶς, a baker; φαρᾶς, a fisher, words very common in the spoken dialect of the present hour; while in νερὸ, for instance, the modern substitute for the ancient ὕδωρ, water, we are delighted to recognise a word hoary with the venerable cousinship of the sea-god Nereus, and his host of silver-footed daughters.

It were out of place in a public and popular exposition to enter at any length into strictly philological details of this kind;[6] but I would remark generally, that a knowledge of the living tongue is of the greatest value to the scientific study of the ancient, inasmuch as it exhibits, in a very singular combination, some of the oldest forms of nascent Hellenism, with some of the more striking peculiarities of the later classics. The modern language in this way forms the necessary complement of the ancient, and presents in fully developed completeness, many of the idioms of the language, of which the style of the classics only gives partial indications.

Let the student of theology also, and the friends of learning in our Scottish Churches, take good note of what was above stated, that some of the most striking peculiarities of modern Greek can be pointed out as characterizing the dialect of the New Testament; so that one of the readiest ways to become familiar with the language of the Christian Scriptures, is to hear lectures on Theology and Church History from Professor Pharmacides or Contogenes, in the modern Christian University of Athens. On this subject I desire to speak with peculiar emphasis, as among other benefits which I have received from the study of the living language of Greece, the more intimate and familiar knowledge of the philology of the New Testament is not the least. Nothing indeed can be more hurtful to the highest interests of sacred literature than that nice circumscription within the limits of a few select authors, called classical, to which verbal scholars of a certain meagre culture, not uncommon in England, are apt to confine their attention.

But I have another argument more seductive with which I would bait my hook, wishing to catch some of those fine verbalists, to whom there is nothing more delightsome in the whole flowing gardens of Hellenic literature, than the gray volumes of Hesychius and Suidas, and the “Great Etymology.” These men, doubtless, amid their assiduous explorations of grim codices, thickly coated with mediaeval dust, are sufficiently aware of the fact, that the manner in which the modern Greeks pronounce their language with its much bespoken iotacism and accents, though not in every title as old as the oracles of Phemonoe, who preceded the Pythoness at Delphi, or that dark Trophonius who spouted dim prophecies beside the clear gushing waters of Lebadea, though in some points demonstrably more recent than the orthoepic precepts of Dionysius the Halicarnassian, is nevertheless of sufficiently long pedigree to claim kindred with the oldest manuscripts now existing; and that in comparison of it, assuredly the bastard pronunciation of the language of Plato, now practised at Oxford and Cambridge, is a sorry piece of the most modern patchwork, whose origin it requires no many-centuried archaeologist to expound.

This being so, it is plain that, from the modern Greeks, who speak with iotacism and accent, we can learn something of Alexandrian and Byzantine tradition, that to a historical mind is worth knowing; whereas, from that vulgar and crude jargon, which our academic men have patched up out of a few nice Erasmian conceits, and a great number of English anomalies, nothing is to be learned that a scientific philologist will not have to unlearn. There is, in fact, just as much affinity between the English method of pronouncing Greek and the method practised by Pericles, so far as that may now be determined, as there is between the high, smart, call of a London cabman, and the slow broad drawl of a Scotch shepherd. The English indeed do not pretend to speak Greek according to any of the known laws of Greek vocalization; they speak Greek as the English speak English; and what a ludicrous jargon this must be to a Greek ear, let themselves judge from the French which some of their own countrymen stammer out in the Parisian hotels.

As for the accents with which they have taught us to emphasize the eloquence of Demosthenes, it is neither the accent of the ancient Greeks, nor the accent of the modern English, but the accent of the old Romans merely, as that was handed down to us through the Roman Church, and has now found its blundering way into our Greek domain, by the pedantry of English prosodians, the stupidity of English schoolmasters, and the carelessness of English professors. The consequence has been, that laborious scholars have been forced to learn in a painful and unnatural way by the eye, what might have been learned in an easy and natural way by the ear; and the doctrine of accents in particular has thus been rendered so difficult, that many very creditable scholars will not be ashamed to say, that they know little about it.

Now, all this tangled wood of error and perversity, through which the student of Anglican Greek must pass, is cleared off at a single stroke, by the mere resolution to study Greek as a living language, and to hear it and speak it only from the first, as it is heard and spoken by the Greeks themselves. The difficult doctrine of accents becomes as easy then, mingled up with the very first elements of living tuition, as it is for a child to sing a nursery rhyme; a thousand facts lurking otherwise timorously in some far corner of lean erudition, rush at once into bright perception and familiar acknowledgement;—the speaking and the hearing scholar begins to know what he is speaking about; and he is no more buffeted about piteously in a confused echo-chamber of words without meaning, and learning without life.

But the supporters of the present perverse practice of pronouncing Greek with Latin accents tell us that they must do so, in order to preserve the proper quantity of the vowels; for that the accent laid on a syllable of short vocal duration, will necessarily make it long. This, however, is a stumbling-block, which the grossness of their own ears, as I have explained at length elsewhere,[7] has cast in their own way. Such an objection never occurred to Cicero, who was as good a Greek scholar as any of our modern syllable-counters; he says distinctly in his book De Oratore, that the Greek accent was as remarkable for variety as the Latin for monotony; and he finds, as every man with ears must, a peculiar beauty of the Hellenic tongue in this very point. In fact, there is no fact more patent to the most vulgar observation of human speech, than that syllables may be accented with a sharp vocal emission, and remain short; while, on the other hand, they may be uttered with a protracted vocal emission, and remain unaccented.[8] This point, therefore, may be dismissed.

Nor is there any more serious reality in the notion on which English-trained scholars are found to enlarge, that they cannot read the poetry of the ancients with any pleasure if they pronounce with accents, because the accent marked on the words so often clashes with the accent of the rhythm. For they overlook the staring fact, that the Latin accent with which they pronounce Greek words, clashes with the flow of the rhythm almost as often as the real Greek accent does. Thus, in the two opening lines of the Hecuba [of Euripides]—

Ἥκω νεκρῶν κευθμῶνα καὶ σκότου πύλας

Λιπὼν ἵν᾽ Ἅδης χωρὶς ᾤκισται Θεῶν.

If in the words σκότου, πύλας, χωρὶς, the progress of the rhythmical intonation necessarily leads the writer to lay the stress of the voice on the unaccented syllables of these words, in the other words, λιπὼν, νεκρῶν, Θεῶν, the spoken accent leads directly to the discovery of the rhythm of the verse, being identical with it. But all these objections to the proper pronunciation of ancient Greek, drawn from the metrical laws of ancient verse, are impertinent and absurd; as we know perfectly well that the poetry of the ancients was not composed on accentual principles at all; and if the Greeks and Romans—as there is not the slightest reason to doubt—either tacitly dropt, or to a considerable extent subordinated the common accent of their daily speech, when solemnly intoning their poetry, we must even do the same. Nor is this a matter by any means of very formidable difficulty—as those who try may know.[9]

My fourth argument in favour of the study of modern Greek—or of Greek as a living language, for I have proved that the old language still exists in full vigour and never was dead—is taken from the theory of education, or Paedeutics, as some would call it, not from the paragraphs of the grammarians. The extraordinary difference between the ease with which a living language is “picked up,”—to use a very expressive phrase—and the difficulty with which a dead language is “crammed down,” has been frequently remarked: a difference so great that whereas German, the most difficult of living languages, can easily be acquired at Bonn or Berlin by a lad of common application in six months, the same amount of Greek, when treated as a dead language, will scarcely be appropriated, according to the present method, by the severe practice of as many years.

The cause of this difference is obvious. While in the study of a living language in the country where it is spoken, the materials of which the language is composed are continually rushing with ample and reiterated floods into the ear and eye of the learner, so that even the stupidest and most backward must of necessity learn a great deal; a dead language, on the contrary, must be fetched painfully out of far and strange corners, in chary quantities, and at certain comparatively rare intervals, and perhaps also, by the unskilfulness of the teacher, presented to the eye only, and the understanding, not to the ear, which is the natural avenue of sound.

Add to this, that the subjects with which the student of a living language in the country where it is spoken, is constantly conversant, are precisely those in which he takes the most vital interest. His daily bread, his daily comforts, his favourite studies, and his necessary knowledge, all come to him in the garb of the new organ of thought which he is appropriating; whereas your classical student oft-times finds it not easy to conjure up a familiar intimacy with a stern old Lacedemonian, or a quick-tongued Athenian, who has been in his grave now for more than two thousand years, and has nothing of very urgent import at this date of time to say to us. To a British boy of the nineteenth century, the iron Duke who stood victorious at Waterloo, and the fiery old Prussian hussar that shook hands with him over that bloody field, are necessarily much more interesting characters than the subtle Themistocles who snared the fleet of Xerxes in the strait of Salamis, or the tragic bard of Eleusis who sung in immortal verse the patriotic triumph which he had shared. This is a difficulty with which teachers of dead languages will always have to contend; only a few of their most energetic disciples will have power of will sufficient to transport themselves into that far distant region of an acquired interest, where their progress imperatively requires that for a considerable season they should learn to sojourn.

But Greek, as I have proved, is not a dead language; and so long as Athens is peopled with thirty thousand living Greeks, and furnished with famous schools, and a flourishing university, and a fair array of vigorous printing presses, (I speak of what I have seen,) the resident student may bring to the aid of his linguistic progress a whole army of familiar associations; and may learn more available Greek in two days from the discussion of the Turkish question in the Αθήνα, or other Greek newspaper, than he could have learned from the pages of the harsh Thucydides in a month.[10]

In whatever subject the young scholar is most deeply interested at the moment, on that subject he will find excellent Greek works written by those men of learning who are now delivering admirable lectures not far from the site of the Lyceum and the Academy. His progress in Greek will thus be ensured without causing the slightest interruption to his professional studies, or to his most dearly cherished trains of thought; and the finest language in the world will be to him no longer a heavy armory which he must put on for occasions of special erudite display; but the living form and drapery of his daily thoughts, the atmosphere which he breathes, the blood by whose pulsation he lives. Casting aside the strange aspect of an acquirement, it will have assumed the permanency of a habit, the inherency of a growth, and the luxuriance of a free vegetation.

But there are yet higher considerations, which, as addressing men and not mere scholars, it would ill become me, at the present critical hour of Eastern politics, to pass over in silence. You have all heard of the Turko-Russian question—a question more fruitful hitherto in debate than in events—as indeed all great political questions in the outset must be more or less—that question, you are aware, involving, as it does, the most important interests of every European kingdom, is also a Greek question; and as such belongs to this Chair, and to the present argument. I wish you to be interested in the Turkish question not merely as Britons, nor for the sake of Manchester muslins only and Glasgow calicoes—though we must have an eye to these things also—but for the sake of humanity and for the sake of the Greeks.

Now it is plain, as was already said, that the barbarous pronunciation of the Greek language fostered on false principles, or rather on no principle at all, by our scholastic men, has been and is, one of the great causes of a divorce between the English mind, so far as it cares for Greek at all, and the actual character, fears, hopes, and fates, of the living Greek people. Certain I am that if all our strong Oxonian and Cantabrigian men had been drilled from their youth in the orthodox Byzantine tradition of iotacism and accent, instead of in the newfangled conceits of that ingenious wit of Rotterdam, and the crass pedantry of routine pedagogues, we should have seen a much more lively display of interest on the Greek side of the Turkish question than the columns of our newspapers bear witness to.

‘Tis not seldom the case, I fear, that our travelled Oxonians return from a hasty peep of Athens and Attica, with an evil report of that oppressed and unfortunate, but ingenious, highly intellectual, and, under all disadvantages, decidedly improving people; perhaps because, as isolated Englishmen, these travellers are not without a certain illiberal ingrown contempt of all foreigners, which they cannot shake off even in favour of Greeks; partly because with all their talk about classical learning, and narrow jealousy of every other branch of liberal education, they really have very minute notions even on their own chosen theme; and are utterly incapable of associating and sympathizing with a people whose philological traditions they have disowned, and of whose history, after a certain arbitrary line of demarcation, they are ignorant.

These men will work them selves into learned raptures over the lid of an old stone-coffin, or the shaftless capital of some petty shrine bearing the gross symbols of some beastly Priapus; dead remnants of the worthless dead enchant them: but for living men and women; for a gipsy-eyed Castrian brunette washing clothes in the bath of the old prophetess of Delphi; for a sun-burnt shepherd boy piping his simple reed, and watching his summer flocks beneath the snow-wreathed peaks of Parnassus; for a stout old admiral Miaulis, with his bushy gray locks flowing over his shoulders, his mild manly eye, and his broad smile of the most sterling good humour, honesty, and truth—all this moves them not beyond the sentimental glance of the moment. “King Otho is a fool, and the Greeks are brutes,”—this is what you will hear them say on grounds which it would not be very complimentary to their hearts or heads curiously to analyze.

Now what I would have you do is the very reverse of all this. Have a respect for Marathon; but remember also Messalonghi. Do not look abroad on the glowing isles and the pine-covered hills of Greece,[11] with the coldly curious eye of a mere lexicographer and a grammarian; and learn to feel that the scanty population of that so often and so cruelly desolated land, has claims on you, as scholars and as men, such as no other country on earth can have, saving only the little peculiar country of the Hebrews. Count it more honourable and more Christian to weep with that people, through their long centuries of sorrow, of which the hard scars and the bleeding gashes are now visible, than to rejoice with them in their hours of victory that are gone, and to triumph with them in the days of their short prosperity. Look not with a haughty eye over the dry stony wilderness of the Byzantine and other mediaeval history;[12] think what millions of Greek men lived then with human hearts in their bosoms as warm as yours; with speculations a good deal more learned and subtle than some of you even in this age of flying books and itinerant libraries, may ever be likely to achieve.

In the most bare records of human history there is many a tale at which a human heart will gladly weep, and a poet’s eye kindle. Shake off, therefore, in your Greek studies, the nice trammels of a merely scholastic classicality. Study Greek as men, with all the mass of your living manhood. Your mere scholar is a puny creature. I wish to make none such. Beware particularly of that narrow and finical system of reading only a few select books, which is so fashionable besouth the Tweed. Honour Thucydides by all means, and luxuriate in Herodotus; but be ashamed to be ignorant of Tricoupi. Have a large heart for everything living—for living Greece particularly, and for the living Greeks; and keep a keen eye lest some secret conclave of cold, calculating diplomatists shall spin some base inhuman compact to cheat that unfortunate people of the brighter future, in which, through their long protracted night of blood and darkness, they have never ceased to believe.[13]

In conclusion, allow me a few words on the practical result to which all these observations lead. You will observe, if what I have stated be true,—and there is no more doubt of it than there is that the sun shines in heaven,—that the whole system of teaching Greek in our Schools and Universities has been very imperfect hitherto, and requires to be remodelled in some parts, and extended in others. Of the ability, energy, and zeal of the learned persons who have presided over our high Schools and Academies in the Greek department, no person can entertain a doubt; but we have been brought by the great advances of the Greek people, since the time of Corais, into a new philological position with regard to them, of which our public Schools and Colleges must not be backward to take note. We have cultivated exclusively the scientific element in teaching the language, and that sometimes with a very blundering machinery; that is to say, we have set forth in imposing array the dissected dead tongue in all its curious completeness, though in Scotland, certainly, with a most inadequate and extremely feeble system of outward appliances.

Now, that scientific element I would have to stand as it is; and not only so, but to stand on a far firmer and broader basis of philological principle than has hitherto been possible. A man who will insist on learning a language without the aids of grammatical science and strict philology, merely as a parrot learns, by sheer frequency of unreasoning repetition, is little better than a parrot. Nevertheless, children do learn their mother tongue, just as parrots do, by the mere frequency of repeated sound; this is the only method of nature with the young; and it must always remain at least the larger half of the method of nature with the adult. Of this half, however, in our famous Schools and Universities, we have hitherto had little or nothing; and it is in respect of this half that our system of teaching Greek in England and Scotland calls for a great reform; the manner of which I have now the honour to propose.

The matter is very simple in its conception, and with only a few sparks of zeal for Greek in certain influential quarters, not at all difficult of execution. What we want is a body of classical teachers, who, to the technical skill in abstract rules, which they already possess, shall add a fluent familiarity with the language as at present spoken and written; who shall be able to speak Greek with their boys on the first day of their schooling, as dexterously as Espinasse talks French. Now, there are two manifest ways of thus equipping our teachers; either by bringing the Greeks to them, or by sending them to the Greeks. Both plans may be practised; the former is the more easy and cheaper for the many—for we are accustomed to starve our students here in Scotland—the latter is the more complete, genial, and efficient for all.

What I propose therefore is, that some living Greeks of education and intelligence should be invited from Athens or Corfu, to act as tutors to the Greek classes in our Universities, and that the classes should be divided into sections of twenty or thirty, to meet at separate hours with these tutors—and that it should be the principal duty of these gentlemen to lecture to their sections, and talk with them familiarly on the most common and interesting subjects in the spoken language of educated Athens; while the Professor should confine himself exclusively to the public critical interpretation of the most difficult ancient classics, and to the exposition of those large views of history, literature, archaeology, and philology, in which it is the proper business of a supreme seminary of learning to deal.

Or, what comes to the same thing, and is in fact much better—I propose that there should be attached to the Greek classes in the University a certain number of TRAVELLING BURSARIES to be given to the best scholars of each year, under the obligation of spending six months at Athens, attending the lectures at the Othonian University, and making the acquirement of the spoken language their principal business during the period of their enjoyment of the bounty. I know from experience that £100 a head would cover all the expenses connected with this arrangement amply; and those young men, when they returned to their country, all fresh and glowing with the atmosphere of the Parthenon, would form a band of Hellenic teachers of the first order, from whom our Schools and Universities might be adequately supplied; so that Scotland might no longer be the home of the cripples, the laggards, and the starvelings, but of the pioneers and the advanced posts of scholarship in these isles.

And now, Gentlemen, I have done. You know what has been the method of teaching Greek in our Schools and Universities hitherto, and you know also what have been its results. A greater expenditure, in some respects, of power—I speak here both of England and Scotland—with a less amount of tangible product, is scarcely to be found in the whole history of human activity. Let us not sit down here quietly and go on to sow seeds that shall bear no fruit, and to plough fields that are destined to the barrenness of an eternal frost. I have taken the liberty of pointing out to you the hope of a more excellent agriculture. Have the courage to give my plan a fair trial. Do not look with a lofty or an indifferent air on an honest advice offered by a practical man, merely because it is new. In our academical studies, as in more important matters, we can never hope to achieve the highest excellence, unless by putting seriously in practice the Apostolic precept,—”PROVE ALL THINGS; HOLD FAST THAT WHICH IS GOOD.”

Notes

| ⇧1 | On the Pronunciation of the Greek Language, Accent and Quantity. Edinburgh, Sutherland and Knox, 1852. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | [We do not reproduce this list of titles, but it can be viewed here.] |

| ⇧3 | TRANSLATION.—”A certain English company proposes to construct a submarine telegraph between the Ionian Islands and a promontory of the Austrian coast. This proposition has already been submitted to the Austrian Ministry. When this telegraph shall have been completed, the news of the East will reach Trieste two days sooner than is now the case.” |

| ⇧4 | FINLAY, in this respect, places it side by side with the Arabic.—Mediaeval Greece and Trebizond, p.6. How far the parallel is perfect in every respect, not being an Arabic scholar, I cannot say. But the Greek seems certainly superior in the length of time, during which it has been the organ of a generally recognised and widely felt national literature. |

| ⇧5 | As a contrast to the purity of the Greek newspaper style, take the following extract, which I made last summer from a German Zeitung. The foreign words are printed in italics:— Brünn, 13th July.—”Seine königliche kaiserliche Apostolische Majestät verfügten sich heute um 6 uhr Morgen auf den Exercierplatz, hiessen die Truppen defiliren, und nahmen sodann die militairischen Etablissments im Augenschein. Hierauf beruhten seine Majestät die Amts localitäten der Staathalterei, Kreisregierung der Landeshaupt-kasse, Finantz, Landes Direction des Oberlands gerichts, der General-procuratur des Landes geriehts und der Staats anwaldschaft zu besehen, nahmen von der Geschäftsführung Ansicht, und liessen sich das Beamten Personale vorstellen. Sodann besichtigte seine Majestät das allgemeine Krankenhaus, und die Spielberger Strafanstalt in allen Details und gaben in das Landhaus zurück gekehrt einige Audienzen.”—See this Babylonish dialect of the German newspapers fully exposed in a work entitled “Die Abstamtnmig der Griechen und die Irrthümer und Taüschungen des Dr. FALLMERAYER, von T. BAR. OW. Munich, 1848.” Anhang, p.22. |

| ⇧6 | Of the essential DORISM of the Neo-Hellenic, the student will find many examples in DONALDSON’s Modem Greek Grammar. Edinburgh: A. & C. Black. 1853. |

| ⇧7 | On the Rhythmical Declamation of the Ancients, Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox. 1853. |

| ⇧8 | The modern Greeks, as is well known, pay no consistent regard to the quantity of syllables, as long or short according to the tradition of ancient Prosodians. There is not the slightest reason, however, why we should allow them to impose this oversight on us. Neither will this point of difference operate as a bar to spoken intercourse between the scientifically trained scholar and the living Greek. An Englishman understands a Scotsman perfectly well, though the latter sometimes draws out a sound which the former cuts short—provided always that the Northern does not invert the accent of the word, or substitute an entirely different vowel sound, in which case mutual understanding becomes seriously impeded. The accent is, in fact, much more an essential part of the spoken word than the quantity; and this is the very reason why it has survived longer. Quantity belonged more to the formal recitation of poets and declaimers, and therefore necessarily vanished with the disappearance of the theatre and the school, the two grand organs of literary training among the ancients. |

| ⇧9 | The Germans, who must be allowed to know something both of philology and of teaching generally pronounce according to the accents. |

| ⇧10 | Of course no reasonable man will suppose here that I mean to say a word against the high merits of Thucydides as a historian. For the mass of massive and manly thought on political life which he has condensed into a comparatively small space, he stands second to no writer, ancient or modern, that I know. But for this very excellence he is a writer for ripe scholars and ripe men, not for immature students, who are tortured by his crabbed style, and who cannot and ought not to have any conception of his political wisdom. In a course of well graduated Greek reading, Thucydides should come immediately after Aeschylus and Pindar, and before Aristophanes, not because this last is more difficult, but because the political matter of the historian is before all things necessary to the full understanding of the comedian, and because it is not expedient that in the years of earnest preparation for the serious business of life, young men should be encouraged to keep precocious company with a maker of jests, however brilliant. |

| ⇧11 | Those who have seen only, the front view of Attica may think that I am speaking vain rhetoric here; but Cithaeron, Parnassus, Helicon, and many of the highest mountains in the interior of Greece, are beautifully wooded. |

| ⇧12 | To those who wish to become acquainted with the state of the Greeks through a study of their mediaeval fortunes, I most earnestly recommend the works, of our learned countryman George Finlay, one of which was referred to in a note above. Mr. Finlay is an ardent, and yet a sober philhellene; he has lived long among the Greeks, and is perhaps the very highest living authority on everything that relates to their mediaeval history and present condition. |

| ⇧13 | The restoration of the Byzantine Empire is at the present moment only a favourite idea of the Greeks, and some of their more ardent friends in this Country; but the preservation of their present territory intact, and the prospective expansion of it, as circumstances may dictate, is what the friends of Greece and of humanity are entitled to demand of the three great powers, by whose interference the present kingdom was established. In so delicate a matter we must not he quick to take offence—much less in a fit of ill humour, perhaps, think of uprooting the tree which ourselves planted, merely because it is not thriving so well in all respects as we fondly think it might have done, had it been watered by an English gardener. |