Johan Tralau

One of the oddities of Ancient Greek culture is how it speaks about justice. Consider the archaic poet Hesiod, who lived in the 8th and/or 7th century BC. He says, insistently, that justice comes afterwards: the punishment comes after the deed. A number of passages in Hellenic literature suggest an intimate association of justice and this “afterwards”. This looks enigmatic, because it seems so… redundant. Why insist on something that is trivial? How could punishment not be subsequent to the act of wrongdoing? So why do the Greeks repeatedly say that justice is exacted afterwards?

I have been wondering about this, silently, for a number of years, making a note every time I have come across these formulations. And then, finally, as I watched the TV series Moon Knight, a bewildering creation, it all dawned on me – the solution, the answer to the riddle, right there, marvellously perspicuous through millennia of obscurity. As far as I know, nobody has asked the question why justice is so often connected to the future in Early Greek literature. It may have seemed trivial to ask about a recurrent formulation that just looks superfluous. But maybe it is not trivial at all. Maybe it does say something important about the Greeks, about their justice – and about ours too, for it raises troubling questions about the possibility of predicting crime and pre-emptively punishing people for what they may do in the future.

In Hesiod’s poetry, justice is brought about by some colourful acts of violence. It is enlightening, in its own outlandish way, that this is the case. About Hesiod the man we know only what he himself says in his poetry, all entirely unreliable. He claims to live in an uninteresting place in Boeotia, and we will leave his biography there. In his great poem, the Theogony, we learn that the god Uranus (Ouranos, Sky) was the first to rule the universe, but he was dethroned and de-something else when his son Cronos cut off his genitals, in a cosmological power grab. Out of the blood drops from Uranus’ body parts, remarkable beings arise, and some of those are the Erinyes, also known as the Furies, the goddesses of revenge and of justice. They bring about future retaliation.

And justice does not stop. When Zeus in turn usurps the throne of his father Cronos, it is, Hesiod tells us, so that he would “pay retribution for the Erinyes of the father”.[1] Cronos’ act of emasculating his father brings about the principle of retaliation, and it will then be applied to himself.

Fair enough. But Hesiod seems to sing of the Erinyes as mythic creatures that are somehow, and in a very special sense, concerned with the future.

This is probably an Erinys, from the Gigantomachy frieze, to be seen in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin (after the ongoing restoration of the museum, that is). We see a female figure about to kill a male, with one great snake nearby and another coiling around the vessel she is holding. The Erinyes are horrifying. We tend to think of them as being associated with snakes, dogs, and the drinking of blood, but much of this is probably later invention; the Athenian dramatist Aeschylus played an important role in jazzing up the tradition. The image from the frieze above is even younger, from the 2nd century BC. Yet already by the time that Hesiod composed his work the Erinyes are terrifying. They are goddesses of revenge bringing about retaliation.

Interestingly, Hesiod stresses that this retaliation is always future retaliation. The Erinyes will punish wrongdoing afterwards – “afterwards” again, and the poet explicitly relates the punishment of the Titans to Uranus’ Erinys as well as to the future: there will be “revenge later”, “later” being μετόπισθεν (metopisthen) in Greek.[2] Further on in the poem, we find more avenging powers, and once again, we find the goddesses of vengeance emphatically related to future retaliation: “they never ever stop… until,” οὐδέ ποτε λήγουσι… πρίν (oude pote lēgousi… prin).[3] Does the creation of the Furies and the Keres – indeed, the idea of justice and retaliation – presuppose the “afterwards”? Why the “later” and “never until”? Why, if these determinations of time are indeed superfluous?

Hesiod appears to stress a correlation between time and justice – some kind of correlation that we need to explain. Later, in his other big poem, Works and Days, he sings about punishment for perjury, and says that those who wrong the goddess of justice, Dike, and their families, will be dealt with “afterwards” (μετόπισθε, metopisthe, again), whereas just people’s offspring – so we learn in the verse that follows – will fare better, precisely “afterwards” (the same word again).[4]

Does this serve as consolation in a universe in which wrongdoers, perjurors, and murderers often escape punishment? In all likelihood. But the vicinity between justice and words meaning “later” might suggest something bigger than that, something more pervasive and telling. Is it trivial to say that punishment is undertaken afterward?

Curiously, a number of other Greek sources suggest a connection between the Erinyes and time. The philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, who lived in the late 6th and early 5th centuries, tells us that “the sun will not exceed its measures. If it would, the Erinyes, the helpers of justice, will seek it out,” (Ἥλιος γὰρ οὐχ ὑπερβήσεται μέτρα· εἰ δε μἠ, Ἐρινύες μιν ἐπίκουροι Δίκης ἐξευρήσουσιν).[5] It may sound strange for the goddesses of vengeance and justice to have to control and persecute a celestial body such as the sun. Yet maybe predictability, and the time sequence of before and afterwards, is what connects the Erinyes and the Sun. If the sun were to grow, and exceed its proper size – that is, its “measures” – time-reckoning would be undermined. The predictable, ordered, systematic sequence of day and night, and the year, would be subverted. But the Erinyes, as “the helpers of Justice”, would chase the sun and correct it, controlling and surveying the proper order of time.

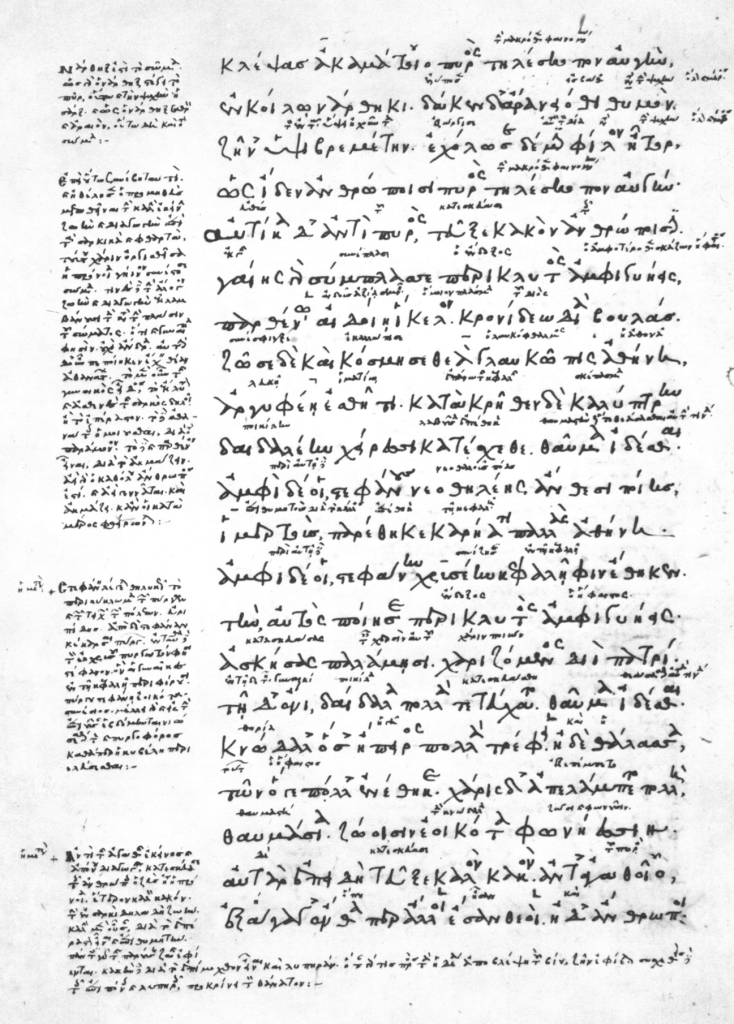

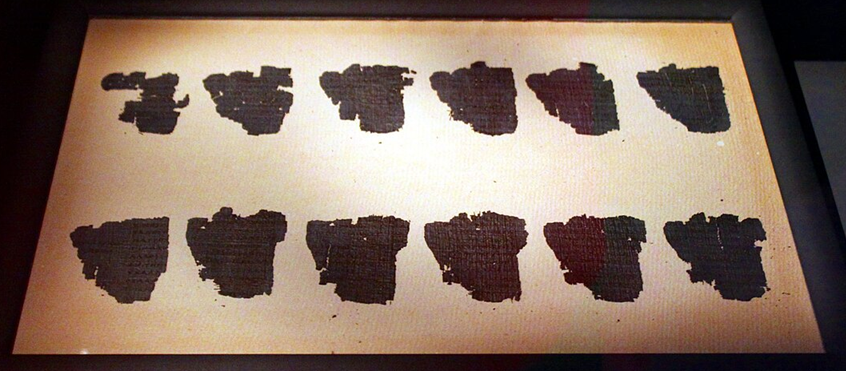

There is a piece of writing called the Derveni Papyrus – an enigmatic work, written around 340 BC and excavated in 1962. Its charred yet legible remains can now be admired in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. The text sports an allegorical interpretation of an older poem, and our unknown author cites the words of Heraclitus that we just read. According to one reconstruction of the text, the author says that Heraclitus’ statement implies that the world is “ordered” (τακτός, taktos), as opposed to arbitrary; the cosmos is predictable and systematic. A little later, in a very damaged part of the text, the author possibly speaks of the “ordained month” (μηνὶ τακτῷ, mēni taktōi), the correct time, precisely in the context of justice (Dike).[6] This is, well, fragmentary, and difficult to understand. Yet time and justice seem to be associated here as well.

Moving backwards again, to the late 7th or early 6th century, we find the Athenian poet and statesman Solon speaking of the timing of justice in a marked way: Dike comes “with time”, or “in due course” (τῷ δὲ χρόνῳ, tōi de chronōi) and it comes “later” (ὕστερον, hysteron).[7] Again, justice is the neighbour of time. And there are possibly similar connections elsewhere in Greek literature.[8]

Why, then, this insistence on time and justice, on the fact that justice is exacted afterwards? The emphasis on “afterwards” seems so insistent, in Hesiod and in other places in Greek literature. Yet Hesiod does not himself explain it. Neither does Solon, or Heraclitus, let alone the Derveni Papyrus. We need a cue, something to bring us on the right path – in the worst case, a cue from another mythic universe. Or possibly in a very good case.

Reverting to the most recent incarnation of the Moon Knight, to be found in Marvel’s TV series, this might be what we discover.

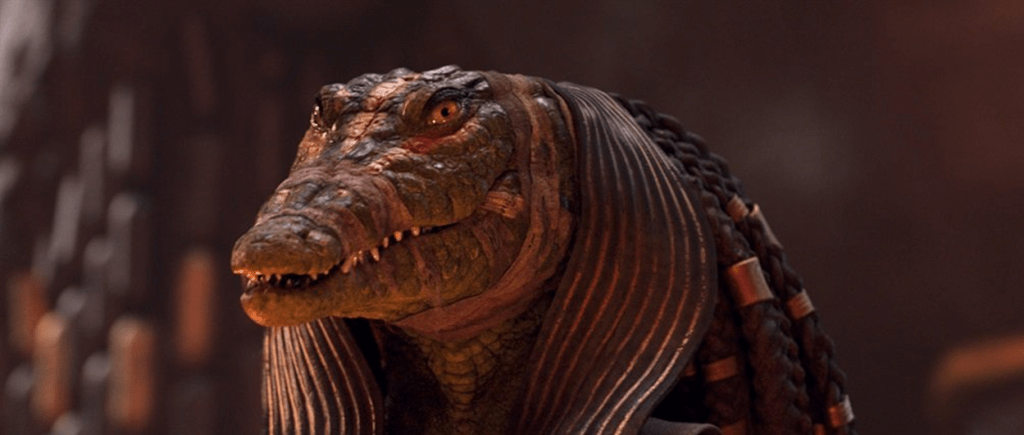

The Moon Knight is the avatar of the Egyptian god Khons(h)u, who punishes wrongdoers for the crimes they have committed. Khonshu needs the body of a human in order to pursue justice. The demon Ammit, by contrast, reckons that it is imperative to punish people before they have done anything wrong. This is, then, a great cosmological battle between two deities of justice and destruction, where one of them claims the right to punish people for their thoughts, and for what they may do in the future. And the latter idea, that of punishing people for their potential future deeds, is actually phrased as justice – it is a conception of justice, surely alien, yet maybe possible.

We should reflect on these ideas about law and morality. At a key juncture in the series, Steven Grant, one of the persons whose body Khonshu needs to fight evil, says (this is Oscar Isaac, with a wonderfully silly British accent): “Sorry – if Ammit judges people pre-evil, like before the fact, isn’t she judging an innocent person?”[9]

A good question. And a good point.

In this myth, then, we learn that one can either punish people when they have committed a crime, or before they have done anything reprehensible at all. According to Khonshu and Steven Grant, the Moon Knight, only the former is justice. Yet Ammit and her minions maintain the opposite, and claim the prerogative to destroy all sinners in advance. The Moon Knight thus allows us to imagine – if only as a frightening counter-image of predictable justice – a system of punishment that sanctions people beforehand, not afterwards, on the basis of some divine or diabolical omniscient big-data prediction of what people think and will do.

This opposite doctrine of justice can be made more interesting, and worth probing in light of normative principles, if we imagine the potential advantages of it. One may think of Minority Report, the 2002 film based – if only loosely so – on a Philip K. Dick short story. The work depicts a future world in which nearly all crime has been eliminated, since there are three clairvoyant persons whose consciousness can foretell the future when they are sedated and connected to a computer. And this means that the police can prevent crime, and most crimes be prevented, and would-be perpetrators punished before the act takes place.

The film raises important questions about the moral implications of such capabilities of prediction, whether unrealistic or not. Is this justice? Would it be justice? While justice is ‘traditionally’ understood as punishment for and hence after the deed, this counter-image may not be one of justice and punishment, but one of total control.

It may seem frivolous to refer to Marvel’s cinematic universe, a different and younger mythic world, masquerading – as the tale does, and as myths do – in an older, more venerable guise (supposedly Egyptian this time). But this terrifying anticipatory notion of counter-justice can help us understand Hesiod’s and other Greek authors’ insistence on the necessary ‘afterwards’ of justice. Justice is exacted after the deed, and it presupposes precisely that ‘afterwards’. If justice were not inextricably bound up with later punishment, it would potentially be the cruel anti-justice of punishing people who are – still – innocent.

Interestingly, Hesiod appears to signal this not only in all those formulations about justice and revenge in close proximity to words signifying ‘later’, but in another important place in the architecture of the Theogony. Uranus engenders children, making Gaia pregnant, but encumbers their birth, filling her with unborn, painful offspring. A very dysfunctional family. The mother tells her children that Uranus must be punished for this, because “he was the first to devise unseemly actions”. This is Gaia speaking, then. Immediately afterwards, Cronos replies, repeating the very same words, “he was the first to devise unseemly actions.”

“He was the first.” “He did it first.” This might sound childish. Yet this is clearly a justification of the plan and the future act of emasculation: it must be done “because” (Hesiod uses the word gar, which indicates that a reason is given) Uranus acted shamefully “first”. The repetition marks the importance of this idea of justice. Gaia and Cronos respond to a potential, unspoken objection regarding the permissibility of cutting off a father’s genitals. They state the reason, and justify vengeance by reference to a series of unseemly acts that have already been committed – that were, in fact, committed first, and the agent of which needs to be punished after and because of these wrongdoings.

This would imply that the verbal exchange before Gaia’s and Cronos’ putsch is the first attempt at a moral justification in Hesiod’s universe. But not only that: it also brings about a conception of justice and time where justice actually presupposes time. “He did it first” is not childish; it harbours an entire world of morality, in which the “first” is a necessary condition of the punishment undertaken afterwards. And the final episode of Moon Knight (yes, massive spoiler alert, avert your eyes) with its standoff between Khonshu and the demonic crocodilesque Ammit on a pyramid in Giza, Cairo, plays out the contrast between justice that presupposes this “first”, and an anti-justice that will do without it.

“I only punish those who have chosen evil,” says Khonshu. “So do I”, replies Ammit, “only I don’t give them the satisfaction of committing it.” The former is punishment, and justice, as envisaged by Hesiod and his gods. The latter is pre-emptive killing.

Reflection on this – admittedly imagined – opposite doctrine of justice from another mythic world will help us see that justice can really only be done ‘afterwards’.

So this may be why Hesiod and the Greeks insist on ‘justice’ and ‘afterwards’. Punishment before the deed, based on superhuman knowledge, super-big data or supposed knowledge about what will happen, is not really justice. It is destruction. Isn’t it quite wonderful to find a much younger, quite corny, yet imaginative and – in its own, weird way – enticing superhero tale that accounts for an enigma in Hellenic poetry? Seen this way, myth is powerful, rewarding, and undeniably alive.

Johan Tralau is Professor of Government at Uppsala University in Sweden. This text draws on a theme from his book Myten om tidens början (The Myth of Time’s Beginning, Ellerströms, Malmö, 2024). He is currently working on a book about the beginning of time and justice in Greek, Mesopotamian and Hittite sources. His next book, The Origins of Political and Moral Philosophy in Ancient Greek Tragedy and Beyond, is forthcoming with Bloomsbury in 2026. He is also the author of Uppsala Arcana, a series of detective novels in Swedish – and hopefully other languages soon. (In his most recent book, two lines in ‘dead languages’ – not Greek or Latin, so take a guess – provide a clue to the solution of the mystery.)

Notes

| ⇧1 | My translation here as elsewhere. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Theogony, 210. |

| ⇧3 | Ibid. 221–2. |

| ⇧4 | Works and Days, 284–5 (and 218, 292, 294, 326, 333, 741). |

| ⇧5 | Diels-Kranz 22 B 94. |

| ⇧6 | See, e.g., column 4.14 in the editions of T. Kouremenos, G. Parrássoglou & K. Tsantsanoglou, The Derveni Papyrus (Leo S. Olschki, Florence, 2006) and A. Laks & G. Most, Early Greek Philosophy VI.1 (Loeb Library, Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2016), but contrast M. Kotwick’s edition (Der Papyrus von Derveni, Sammlung Tusculum, Berlin, 2017) and most recently the editions of Valeria Piano at 4.14 and Richard Janko at 44.14 in Glenn Most (ed.), Studies on the Derveni Papyrus, II (Oxford UP, 2022). |

| ⇧7 | Solon fr. 4.16; 8.13. |

| ⇧8 | Anaximander, Diels-Kranz 12 B 1; Homer, Iliad, 15.204. |

| ⇧9 | Moon Knight, Season 1, Episode 2. |