Mateusz Stróżyński

Bilbo meets Smaug, the enormous dragon inhabiting the dwarves’ palace he conquered and burned inside the Lonely Mountain. Bilbo – fulfilling his ‘burglar’s’ mission – enters the dragon’s lair, invisible, protected by the Ring. Unnoticed by Smaug, the hobbit steals a cup and returns to his dwarf companions to report on his reconnaissance. When the dragon awakes, he notices that one of the treasures is missing and falls into a rage. For the next meeting he is prepared, and although the invisible hobbit sneaks in silently, the dragon detects his scent – a smell utterly unknown to him – and begins a conversation.

In this exchange between Bilbo and Smaug, we observe an interesting reversal of the situation with Gollum. Here too there is a deadly play of riddles and a confrontation with a monster, perhaps modelled to a certain extent on Book 9 of the Odyssey, as I suggested in my previous essay. Here, however, the hobbit, having learned from previous experience, does not begin by revealing his name, but acts like Odysseus in his encounter with Polyphemus: he conceals his identity by means of riddles.

Bilbo recounts to Smaug his earlier adventures and those of his companions, just as Odysseus, when questioned by Polyphemus, reveals where he comes from and what he has been through, while hiding his true name. The game begins with Smaug’s asking, like Polyphemus: “Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?” Bilbo answers:

“You may indeed! I come from under the hill, and under the hills and over the hills my paths led. And through the air. I am he that walks unseen.”

“So I can well believe,” said Smaug, “but that is hardly your usual name.”

“I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I was chosen for the lucky number.”

“Lovely titles!” sneered the dragon. “But lucky numbers don’t always come off.”

“I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me.”

“These don’t sound so creditable,” scoffed Smaug.

“I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; and I am Barrel-rider,” went on Bilbo beginning to be pleased with his riddling.

“That’s better!” said Smaug. “But don’t let your imagination run away with you!” (Ch. 12, ‘Inside Information’)

Tolkien immediately comments on this ritualized dialogue between hero and monster, writing: “This of course is the way to talk to dragons, if you don’t want to reveal your proper name (which is wise), and don’t want to infuriate them by a flat refusal (which is also very wise). No dragon can resist the fascination of riddling talk and of wasting time trying to understand it.” The author’s warning acquires particular significance when contrasted with the earlier riddle-game with Gollum.

At a certain, crucial point of this game of riddles, Bilbo compliments Smaug’s “diamond waistcoat,” which has formed over the years as the dragon lay upon his hoard of gold and jewels – the treasure had simply stuck to the creature’s skin, creating an additional protective layer, a kind of natural armor. Bilbo praises it because he wants to examine the dragon more closely, especially from underneath. The monster takes the bait, and showing off his magnificent appearance allows the hobbit to spot a weak point in the armored body: “Dazzlingly marvellous! Perfect! Flawless! Staggering!” exclaimed Bilbo aloud, but what he thought inside was: “Old fool! Why, there is a large patch in the hollow of his left breast as bare as a snail out of its shell!”

Having carefully inspected the dragon’s belly, Bilbo could think of nothing more than getting away as quickly as possible. He returned to his companions and told them about his conversation with Smaug. He was displeased that the dragon managed to draw so much information from him about the company, and he vented his anger on a thrush who happens to be listening nearby. Thorin, the leader of the company and heir to the kingdom under the Lonely Mountain, defended the bird:

“Leave him alone!” said Thorin. “The thrushes are good and friendly—this is a very old bird indeed, and is maybe the last left of the ancient breed that used to live about here, tame to the hands of my father and grandfather. They were a long-lived and magical race, and this might even be one of those that were alive then, a couple of hundreds of years or more ago. The Men of Dale used to have the trick of understanding their language, and used them for messengers to fly to the Men of the Lake and elsewhere.”

Tolkien thus suggests that the thrush is a magical and wise bird, capable of communicating with humans and destined to play a significant role in the fate of the dwarves. At the end of the discussion, Balin, one of the dwarves, emphasizes that the crucial piece of information Bilbo has obtained is the existence of a gap in Smaug’s diamond armor: “It may be a mercy and a blessing yet to know of the bare patch in the old Worm’s diamond waistcoat.”

Smaug, believing that the hobbit and the dwarves were collaborating with the people of Esgaroth in trespassing into his lair, attacked the city and began to plunder it mercilessly. The leader of the town’s defenders was Bard, an excellent archer and a brave man, descended from a royal line. When he had only one arrow left and was about to shoot it at the dragon circling over the city, an old thrush—the same bird that had listened to Bilbo’s conversation with the dwarves—flew onto his shoulder and, in a human voice, told Bard to aim at the exposed spot under the dragon’s left breast. The archer struck the monster in that spot and killed it. Smaug crashed down onto the ruins of the city he had set ablaze.

The context for this passage contains structural elements strikingly similar to the famous motif of the ‘Achilles’ heel’. Interestingly, this motif does not appear in Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey, nor in Virgil’s Aeneid; it is thus difficult to determine clearly whether it formed part of the Achilles myth already in the Homeric or pre-Homeric period. Only in Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica is there a reference to Thetis attempting to make her son invulnerable to wounds, but there is no mention of an immersion in the Styx (Apoll. Rhod. 4.869–72; see also Statius Ach. 1.133–4, 269–70, 480–1). According to Carlo Odo Pavese, five literary versions of Achilles’ death can be found in the ancient tradition, attributing responsibility to Paris and Apollo to varying degrees.[1]

In Book 19 of the Iliad, there are hints that a man and a god killed Achilles together, though no names are mentioned; in Book 21, Apollo’s name appears in that context (Il. 19.416–17; 21.277–8). In the final book of the Odyssey, however, when Agamemnon’s soul recounts to Achilles’ soul the struggle over his body, the funeral, and the games held in his honour, neither Apollo nor the manner of Achilles’ death is mentioned (Od. 24.35–94).

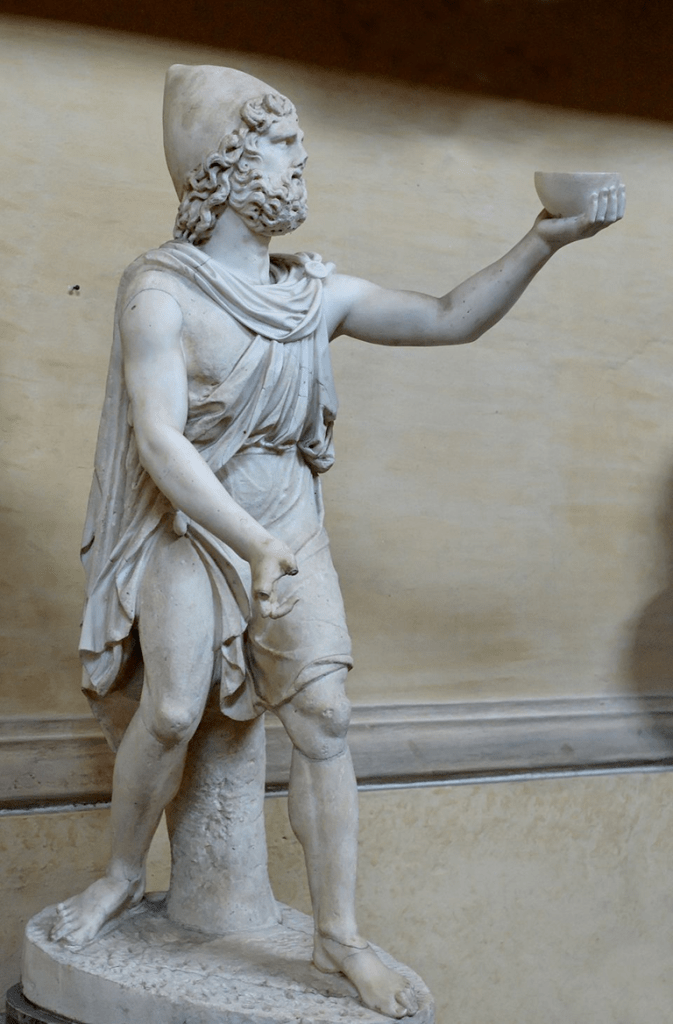

Simonides, in his elegy on the Battle of Plataea, writes that Achilles fell like a felled tree and attributes his death to Apollo (fr. 11 West). Pindar, similarly, says that Apollo defeated the son of Peleus in the guise of Paris (Hyginus gives the same version).[2] Horace also attributes Achilles’ death to Apollo, repeating the tree-felling motif.[3] Virgil is more specific in the Aeneid, saying that Paris’ bow and arrow were guided by Apollo.[4] Even more detailed account is given by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, where he describes a scene in which Apollo addresses Paris directly, pointing out Achilles to him and encouraging him to kill the hero.[5] Then the god turns Alexander’s bow toward Peleus’ son, guiding the flying arrow himself. Only in later versions, however, do we encounter accounts in which the arrow strikes the heel.

Alessandro Barchiesi has suggested that the image of cutting down a tree may be an allusion to the mortal blow to the heel (the blow falls on the lower part of the mighty tree), though this remains speculative. In any case, it is only in Pseudo-Apollodorus that we get the complete picture of the fatal ‘Achilles’ heel’: the son of Peleus is struck by Paris and Apollo under the Scaean Gate in the only place where he could be wounded: εἰς τὸ σφυρόν, in the heel.[6]

It seems that Tolkien, at some level, refers to this myth, since the structural similarities are striking. In both cases, we are dealing with a figure who cannot be killed through ordinary physical force – in one case, a magnificent, undefeated hero; in the other, a terrifying monster. Both Achilles and Smaug have only one vulnerable spot on their bodies, though for entirely different reasons – in Achilles’ case, it is the divine protection, in Smaug’s, a purely natural phenomenon. Over the years the gold and precious gems on which he was lying became attached to his vulnerable chest and belly, creating a protective layer. Yet during his first conversation with Smaug Bilbo spotted a single soft point in it.

The element of collaboration between god and man, already present in the Iliad and emphasized by both Greek and Roman poets, seems clearly marked in Tolkien through the presence of the thrush helping Bard. The motif appears of a deity influencing an archer and advising him with a whisper whom to shoot, for example, in Book 4 of the Iliad, where Pandarus, persuaded by Athena, shoots at Menelaus, thereby breaking the truce (Il. 4.86–147). However, in that scene the daughter of Zeus does not direct the arrow to its target but diverts it from Menelaus, “like a mother who brushes away a fly from her child lying in a sweet sleep.” (Il. 4.130–1)

Ultimately, the arrow strikes Menelaus’ belt and merely wounds him. The scene with Bard in The Hobbit seems similarly structured particularly to the aforementioned passage in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which Apollo, in his divine form, first addresses Paris directly, indicating the target to him, and then guides his hand – and in a sense, also the arrow. In Tolkien’s story, the thrush – a bird Tolkien fleetingly suggests to be of “a long-lived and magical race” – sits on Bard’s shoulder to advise him on how to kill the dragon, pointing out the vulnerable spot, just as Apollo does for Paris in Ovid.

Bard’s reaction, as he speaks aloud to his arrow, also has a distinctly Homeric tone:

“Arrow!” said the bowman. “Black arrow! I have saved you to the last. You have never failed me and always I have recovered you. I had you from my father and he from of old. If ever you came from the forges of the true king under the Mountain, go now and speed well!” (Ch. 14, ‘Fire and Water’)

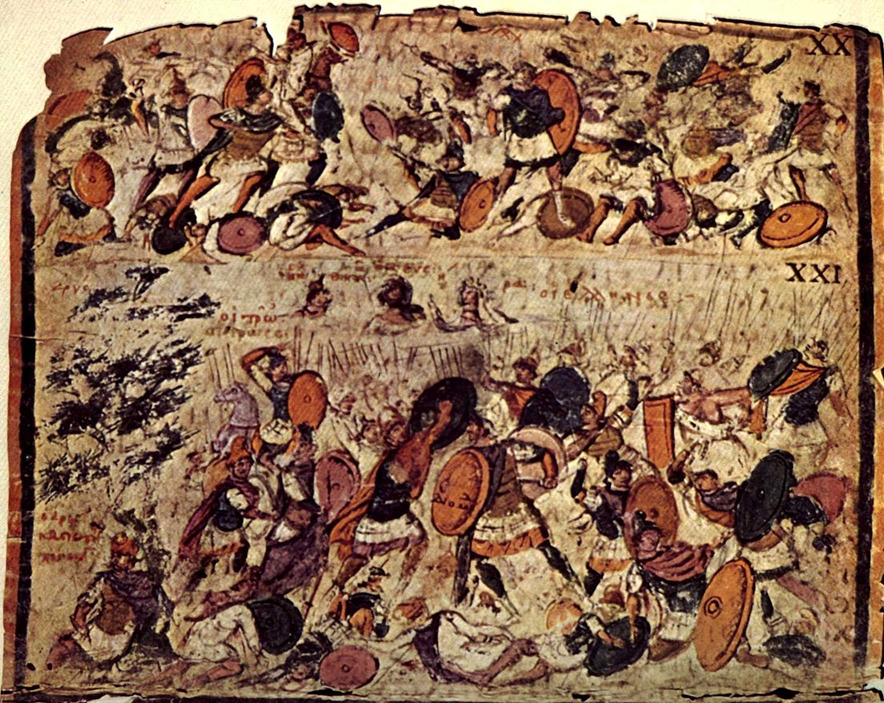

The hero both personifies the arrow, treating it almost as part of his own personality, and recalls its history and lineage. This too is present in the Iliad, in the magnificent retardation consisting of a lengthy description of the origin of Pandarus’ bow, followed by a crescendo of tension as the archer prepares to shoot (Il. 4.105–26). A similar relationship between archer and weapon, the gradual building of tension as the archer takes aim, and the dramatic release of that tension in a crucial moment for the epic action appear in Book 21 of the Odyssey, where Odysseus shoots an arrow through a row of standing axes (Od. 21.392–423).

Another similarity lies in the setting: Achilles’ death at the Scaean Gate occurs at the moment of Troy’s fall; Smaug’s death takes place during the destruction of Esgaroth. In both cases, a mighty aggressor perishes. Both the title of The Hobbit’s fourteenth chapter – ‘Fire and Water’ – and the vivid descriptions of Esgaroth burning in the night seem to evoke the conflagration of Troy, which fills almost the entire second book of the Aeneid. Interestingly, Smaug is a monster, and Bard, a great hero and the founder of the lineage of kings, while, in the epic tradition, Achilles is no monster, although he has many flaws – and, more importantly, his killer, Paris, is not a typical heroic figure at all.

As I have pointed out, the similarities are structural but seem strong enough to suppose that, again, the Classical epic tradition, contained in Tolkien’s “leaf-mould of memory”, have suggested to him the way to kill invincible dragon: to shoot him with the arrow at his vulnerable heel. Even if the heel is on his chest, the epic tradition lives on.

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His most recent books are The Human Tragicomedy: the Reception of Apuleius’ Golden Ass in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Century (ed., Brill, Leiden, 2024) and Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World: Faces of Being and Mirrors of Intellect (Cambridge UP, 2024).

The first essay in this series, “Homeric allusions in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit“, can be read here.

Further Reading:

J. Burgess, “Achilles’ heel: the death of Achilles in ancient myth,” Classical Antiquity 14 (1995) 217–44.

A. Barchiesi, “Simonide e Orazio sulla morte di Achille,” ZPE 107 (1995) 33–8 (English translation: in Greek Literature in the Roman Period and in Late Antiquity, ed. G. Nagy, Routledge, London, 2001, 93–100).