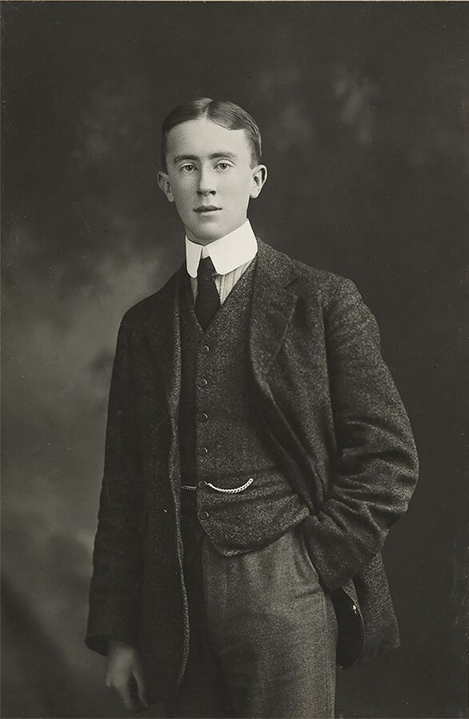

Mateusz Stróżyński

In a previous piece dedicated to J.R.R. Tolkien, I have emphasized the importance of Classical education in general, and Latin in particular, for this author. However, when we look at his most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, which gave him popularity during his life, these texts don’t seem to abound in Classical references. What stands out for most of readers is Nordic mythology, not Ancient Greece. Some scholars, such as Tom Shippey and John Garth, have claimed that Tolkien either was “hostile” to the Classical tradition,[1] or “turned his back enthusiastically on the Classics”.[2]

On the other hand, in an early draft of the chapter “Minas Tirith” (in the third volume of The Lord of the Rings), where Tolkien describes the procession of various vassals of the Kingdom of Gondor, who enter its capital to defend it against Sauron’s assault, Tolkien wrote in the margin “Homeric catalogue”.[3] As John Kevin Newman argued in his paper, the influence of Tolkien’s Classical education can be seen in his epic works, although it is not explicit.[4]

In this piece I would like to point out some interesting similarities between Tolkien’s first novel, The Hobbit, and Book 9 of the Odyssey, that is, Odysseus’ encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemus. Even on a general, mythological level, both Odysseus and Bilbo are archetypal tricksters: mythical figures whose strength is in cunning and deceit rather than (only) in physical strength or combat prowess. Odysseus is πολύτροπος (polutropos), “of many turns”, and πολύμητις (polumētis), “of many wiles”, so he outsmarts all of his many adversaries both on his way to Ithaca and on the island itself. Bilbo, much more explicitly, is given the role of a “burglar” in the expedition of the thirteen dwarves to the Lonely Mountain. Bilbo also finds a magical Ring, which gives him invisibility, and the combination of invisibility with his perceptiveness and wits makes Bilbo πολύτροπος as well, albeit in his own hobbit way.

The first episode of The Hobbit I will discuss is Bilbo’s encounter with Gollum (Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”). Gollum, a notoriously gangling creature, one of the most significant characters created by Tolkien, doesn’t seem to have much in common with a one-eyed giant of the Odyssey 9. However, the land of the Cyclopes is described by Homer as that of Κυκλώπων… ὑπερφιάλων ἀθεμίστων (Od. 9.106). So the Cyclopes are arrogant and lawless folk. Moreover, they are unsocial and live alone, on the peaks of mountains in hollow caves. That said, to give the Cyclopes their due, they do have wives and children, unlike Gollum, who is not only lawless but his isolation is total. There is no question of family. He was expelled from his own as a punishment of his wickedness, as we learn in The Lord of the Rings. Gollum also lives in a cave, but under the mountains rather than on its summit. Of course, the most visible contrast is that of size – and the number of eyes.

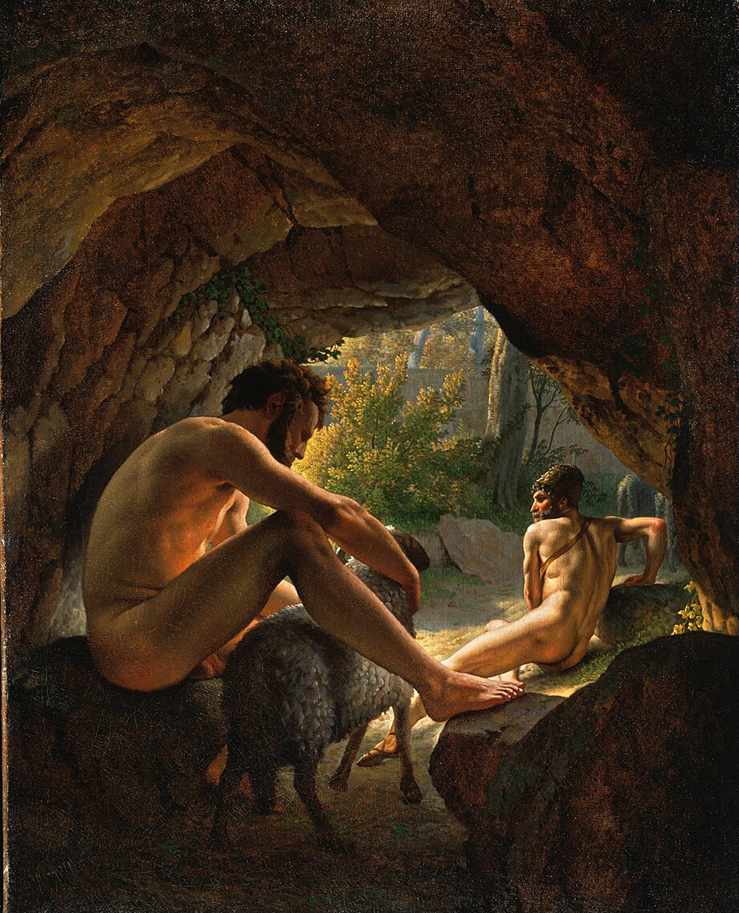

Odysseus and his companions enter the cave of Polyphemus, who is absent at the time, and prepare a meal for themselves from his supplies (Od. 9.216–33). Quite similarly, Bilbo (who is lost and without his companions) arrives at Gollum’s dwelling place and takes something which belongs to him: his golden Ring. In both cases, when the “host” returns, a confrontation between the characters ensues. Polyphemus begins by asking Odysseus: “Who are you, strangers? Whence do you sail over the watery ways?” (Od. 9.252) Although it is Bilbo who first sees Gollum and asks him who he is, Gollum pays no attention to the question and asks his own in turn: “What iss he, my preciouss?”

In the Odyssey, Odysseus reveals only that they are Achaeans, travelling home from Troy, but he conceals his own identity. Later, Polyphemus asks again for Odysseus’ name: “Give it me again with a ready heart, and tell me your name straightway, so that I may give you a stranger’s gift at which you may be glad.” Odysseus, however, has no intention of revealing his name and says that he is called Οὖτις (Outis), Nobody (Od. 9.364–7). Odysseus’ answer is a riddle, except that the Cyclops does not realize that Odysseus is playing a deadly riddle-game with him. Polyphemus believes that the stranger has in fact revealed his true name and promises him, in a perverse way, that, as his guest-gift (ξεινήιον, xeinēion), he will be eaten last.

Bilbo, by contrast, acts in a completely opposite manner. Unlike Odysseus, he recklessly and immediately reveals his first and last name. Polyphemus’ ignorance of Odysseus’ name prevents him from taking revenge, when Odysseus blinds him and escapes his cave with his companions. When the other Cyclopes, on hearing his cry, run to help, Polyphemus shouts, “Nobody is killing me by trickery, not by force.” (Οὖτίς με κτείνει δόλῳ οὐδὲ βίηφιν, Od. 9.408). Thus, Odysseus’ riddle becomes a riddle to the other Cyclopes, who, unable to grasp the meaning of it, think Polyphemus went mad. Polyphemus, who earlier failed to solve the riddle of the hero’s identity, is now blind, groping in darkness, unable to see his persecutor, defeated by someone more cunning than himself.

While Polyphemus does not know the name of his persecutor, Gollum knows it from the very beginning, because Bilbo’s polite manners got the better of him and he introduced himself to the creature. Bilbo’s name is not a riddle, but, interestingly, Gollum’s name is. It is not a name, it’s just a gurgling sound that he makes, while his true name and identity remain hidden in The Hobbit and become an important riddle that Gandalf finally solves in The Lord of the Rings. The whole encounter between Bilbo and Gollum is a game of riddles. The danger is identical to that in the Odyssey: if Gollum wins, he will eat Bilbo. But if he loses, he is supposed to lead Bilbo out of the darkness.

When Bilbo wins (by a little bit of trickery and luck), Gollum breaks his promise (lawless creature that he is, like Polyphemus, who perverts the idea of the guest-gift) and tries to kill and eat Bilbo. Thanks to the Ring, Bilbo escapes; the similarity here is that, while in the Odyssey Polyphemus is blind and cannot see Odysseus, shouting his name in desperation, Gollum is also made blind by the magical Ring. He cannot see his enemy, but still loudly curses him, shouting his name in the dark. Polyphemus is finally able to take his revenge, when Odysseus recklessly introduces himself to the Cyclops, because the giant prays to his father, Poseidon, to persecute Odysseus. In Tolkien, Bilbo introduces himself at the beginning, not at the end; since Gollum is weak and helpless, his curses on Baggins have no consequence. However, in The Lord of the Rings, like in the Odyssey, a powerful god, Sauron, learns from Gollum who stole his Ring and begins to persecute Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo.

There is yet another episode in The Hobbit which seems similar to Odysseus’ encounter with Polyphemus. In Chapter 9 (“Barrels out of Bond”) the company of the dwarves ends up in the dungeons of the Elven-king in Mirkwood. The dwarves were imprisoned because, in their desperation, they disturbed the peace of the elves, having lost their way while travelling through their forest kingdom. This seems like a faint echo of the troubles caused constantly by Odysseus’ companions in the Odyssey, where he has to rescue them. Also, the dwarves refuse to reveal the purpose of their journey to the king (another game of riddles). Bilbo is not held captive, thanks to his Ring, but lives in the king’s palace, invisible, stealing food and pondering how to help his imprisoned companions.

After some time, Bilbo finally “learned how the wine and other goods came up the rivers, or over land, to the Long Lake.” The goods were regularly floated downstream in barrels, sometimes tied together into huge rafts. Bilbo’s plan was to place the dwarves inside empty barrels and smuggle them to Esgaroth, the Lake-town. And here lies the similarity to Odysseus’ trick which helped him to escape Polyphemus’ cave. Odysseus noticed that Polyphemus lets his sheep out of the cave every day and decided to use that routine to free his companions and himself. In both cases, some part of the property of the one who imprisoned the protagonist regularly leaves the prison without arousing suspicion. In Homer, these are Polyphemus’ flocks, in Tolkien, it is the barrels of wine.

Odysseus ties Polyphemus’ rams together in threes and ties his companions beneath their bellies, while he himself clings to the underside of a great ram (Od. 9.425–36). The blinded Polyphemus is trying to be cunning, so he is feeling each sheep, but is unable to detect that his prisoners are being smuggled out under their bellies. In Tolkien, Bilbo locks his companions in barrels, thus making them invisible to the elves. Of course, he cannot lock himself inside a barrel, which he realizes only at the very last moment. Odysseus had thought of this danger in advance and decided to cling to the belly of a mighty ram, to which he could not tie himself. Bilbo has a similar idea, clinging to a barrel just as Odysseus did to the ram. Although he does not travel exactly under it, like Odysseus, Bilbo, nonetheless, constantly struggles to stay on top of it:

he found it quite as difficult to stick on as he had feared; but he managed it somehow, though it was miserably uncomfortable. Luckily he was very light, and the barrel was a good big one and being rather leaky had now shipped a small amount of water. All the same it was like trying to ride, without bridle or stirrups, a round-bellied pony that was always thinking of rolling on the grass.

At one point, however, it turns out to be a good thing that Bilbo has to hold on to the barrel from underneath – just like Odysseus clinging to the ram – because otherwise he would not have been able to float under the low arch of the gate.

It is not just the use of a routine that characterizes both plans of escape. The second point of similarity between the Odyssey and The Hobbit is that Bilbo takes advantage of the drunkenness of the guards. He does not make them drunk with wine himself, as Odysseus does with Polyphemus, but, instead, it is the elves themselves who begin to drink the wine that was to be served that same night at the king’s feast. However, Tolkien emphasizes that this was a special drink:

Luck of an unusual kind was with Bilbo then. It must be potent wine to make a wood-elf drowsy; but this wine, it would seem, was the heady vintage of the great gardens of Dorwinion, not meant for his soldiers or his servants, but for the king’s feasts only, and for smaller bowls not for the butler’s great flagons.

Homer also devotes considerable space to describing the dark, sweet wine that is used by Odysseus to deal with Polyphemus:

“With me I had a goat-skin of the dark, sweet wine, which Maro, son of Euanthes, had given me, the priest of Apollo, the god who used to watch over Ismarus. And he had given it me because we had protected him with his child and wife out of reverence; for he dwelt in a wooded grove of Phoebus Apollo.” (Od. 9.196–202).

The poet suggests that the wine was especially strong, so that one cup had to be mixed with twenty measures of water (208–10).

In any case, it is thanks to the wine that both the Cyclops and the elf-guards fall into a deep sleep, which allows Odysseus and Bilbo to escape with their companions. The difference is, however, that Odysseus mercilessly blinds the drunk Polyphemus, whereas Bilbo – with his typical hobbit politeness – not only has no intention of harming the elves, but even returns the keys at the end, so that their punishment for their indulgence in wine may be less severe. The escape itself, the barrel-ride, is described in The Hobbit as something quite ridiculous, if extremely uncomfortable; in Homer, there may be something funny about poor Polyphemus trying to feel the sheep, unaware that his prisoners are hidden under them, but there is also a danger of immediate detection and subsequent revenge.

I regard these parallels between Book 9 of the Odyssey and The Hobbit as real. However, I don’t think that Tolkien was necessarily inserting these allusions into his novel deliberately and consciously, to evoke Homeric associations. In one of his letters, he observes that “one’s mind is, of course, stored with a ‘leaf-mould’ of memories (submerged) of names, and these rise up to the surface at times” (Letter to Graham Tayar, 4–5 June 1971). This is often used by scholars to argue that, although Tolkien didn’t like to admit to influence, there is value in searching through the potential “leaf-mould” of his mind. And it would be very surprising, given his education and his love for mythopoeic literature of antiquity and the Middle Ages, if the Homeric epic poetry were not, in fact, an important part of Tolkien’s literary memory.

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His most recent books are The Human Tragicomedy: the Reception of Apuleius’ Golden Ass in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Century (ed., Brill, Leiden, 2024) and Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World: Faces of Being and Mirrors of Intellect (Cambridge UP, 2024).

Further Reading

R. Arduini, G. Canzonieri, C.A. Testi (edd.), Tolkien and the Classics (Walking Tree Publishers, Zurich/Jena, 2019).

M. Fenwick, “Breastplates of silk: Homeric women in The Lord of the Rings,” Mythlore 21.3 (1996) 17–23.

J.K. Newman, “J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: a Classical perspective,” Illinois Classical Studies 30 (2005) 43–62.

M. Stróżyński, “Antyczna tradycja epicka w Hobbicie J.R.R. Tolkiena,” Meander 70 (2015) 131–47.

Notes

| ⇧1 | T. Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century (HarperCollins, London, 2000) 314. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | J. Garth, Tolkien and the Great War: the Threshold of Middle-earth (HarperCollins, London, 2003) 42. |

| ⇧3 | M. Fenwick, “Breastplates of silk: Homeric women in The Lord of the Rings,” Mythlore 21.3 (1996) 17–23. |

| ⇧4 | J.K. Newman, “J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: a Classical perspective,” Illinois Classical Studies 30 (2005) 43–62. |