Krystyna Bartol

Adam Mickiewicz, the great Polish Romantic poet (1798–1855),[1] in his magnificent epic, Pan Tadeusz, voiced his dream:

Would I might live to see the happy day

When under the thatched roofs these books shall stray.

(transl. Kenneth MacKenzie)[2]

“Straying under the thatched roofs” means not only “reaching a wide audience” in general, but also, and perhaps most importantly, “gathering wide popular readership”.[3]

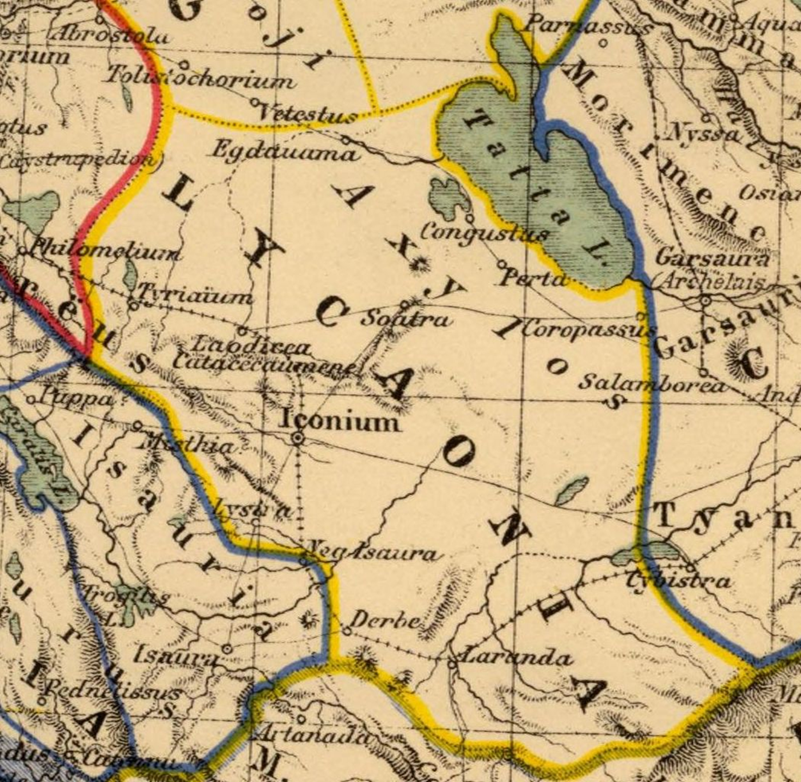

This universal dream of poets came true for Homer, at least. The Iliad and the Odyssey were stock texts for everyone until Late Antiquity, for both well-educated people with refined literary tastes, and those who were just beginning to learn to read and write. Homer’s words resounded through both ‘core and periphery’, wherever Greek was spoken, even to Eastern backwoods provinces of the Roman Empire, where major urban centres did not exist for vast stretches of territory, and small towns became the cultural heartlands of networks of villages. An example of such a district during the first centuries AD was Lycaonia (Λυκαονία), a region in the interior of Asia Minor, called Anatolia at the time.

The only major city in Lycaonia was Iconium (Ἰκόνιον, modern Konya in Turkey), which was located in the western part. Otherwise, the population centred around small towns and villages. It is worth recalling that Iconium was one of the destinations of the missionary journeys of Saint Paul and Saint Barnabas in AD 46/47, as is attested in the Acts of Apostles (Ac. 14:1–6). Saint Thecla, a follower of Paul the Apostle, is said to have been born in Iconium.

Christianity also reached other areas of Lycaonia quite early, as is evident from surviving inscriptions in both prose and verse that confirm the existence of Christian communities in Laodicea Combusta (Λαοδίκεια Κατακεκαυμένη, i.e. ‘Burnt Laodiceia’,[4] modern Ladik) in the Phrygian-Lycaonian borderland, and in the territory of the so-called Axylon (lit. ‘treeless country’), a steppe region west of the Big Salt Lake called Tatta (modern Tuz Gölü), which contains the small town of Congussus or Congustus (Κόγγουστος, probably modern Altınekin) and, around 15 km to the west, the village of Dedeler.

There is evidence of literary culture in this rural environment. And although we know little about the level of education there, we can surmise that there were schoolmasters through whom at least elementary literacy reached the inhabitants of the villages.

Whatever the religious affiliation of individuals, pagan Hellenic culture was perpetuated by the centrality of the Classical canon to the educational system. It provided a reference point for the expression of Lycaonians’ thoughts and feelings, even in the middle of nowhere, as with the village of Dedeler. Ten Greek inscriptions were found in this country landscape, dating from the 3rd century AD onwards. Three of these are in verse, and reveal the villagers’ love for Homer. They are epitaphs written in Homeric language, style and metre. Homeric poetic conventions were still alive then, and seem to have been accepted and practised, with minor or major linguistic, stylistic and metrical errors, simply as a part of the local literary inheritance, regardless of an author’s religion or that of his readers.

Commemorating the dead of the Axylon in the language of archaic epic poetry was, as Peter Thonemann rightly concludes, “a quite extraordinary cultural phenomenon in its own right, as if the cattle-farmers of modern Tennessee were to compose their tombstones in the language and style of Beowulf.”[5] We do not know who composed the inscriptions. It is assumed that it must have been someone with a local reputation for erudition, for example, a schoolmaster who composed poetry ‘on the side’. Yet what he composed, and what the stonemason carved into the stone, must have been easily comprehensible to the family members of the deceased, as well as to anyone passing by the stele. The inscriptions from Dedeler, like others from the Anatolian steppe region, are identified as Christian not on the basis of their content – as we shall see – but because of particular functions (e.g. those of the presbyter and deacon) and places (e.g. κοιμητήριον, koimētērion, an early Christian term for a cemetery, literally ‘resting-place’) that are mentioned; the presence of the letters alpha and omega (which together symbolize God, cf. Revelation 1:8, 21:6, and 22:13); and other Christian symbols that are inscribed on the stones: signs of the cross, Christograms, staurograms, and occasional images of vines and peacocks.

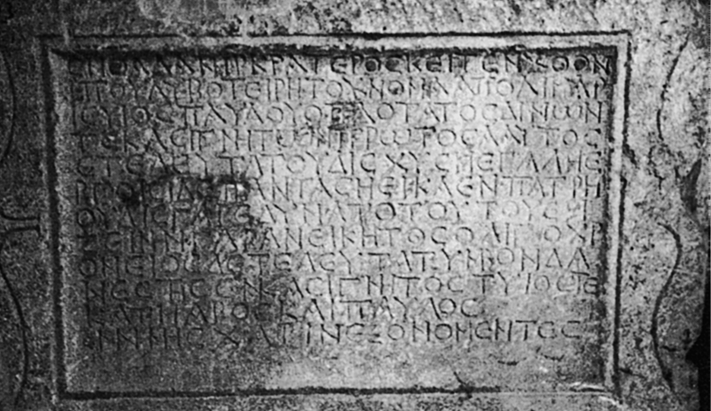

One inscription from Dedeler is a verse epitaph from around the 4th century AD dedicated to Venavia, the wife of the presbyter Phronton. Her life is celebrated in nine hexametric verses spread across seventeen lines carved on the panel of the limestone stele. The panel is surmounted by two arches, with rounded pilasters flanked by peacocks facing each other. On the left border of the panel a vine-tendril pattern is visible.

I reproduce this text, and others, in hexameters:

1 + ἔνθ’ ἄλοχος πινυτὴ [ἀν]|δρὸς κρατεροῦ ὑπόκιτ̣[ε]

2 τοὔνομα Οὐεναυία π[ι]νυτόφρονος ἶδος ἔχ̣̣[ου]|σα·

3 τῆς δ’ ἤτυ χαρίεν [κὲ] ἐράσμιον ἦτο πρόσωπ[ον],

4 ὄμματ(α) δ’ ὥστε βοός, μιν[υν]θαδίη δ’ ἐτελεύτα·

5 ᾤχε̣το δ’ ἰς Ἀΐδαο λιποὺς φάο[ς] ἠελίυο·

6 πε͂δά τε νηπίαχ̣[ον] ἀριστῆόν τ’ ἅμα πόσιν

7 [ἐ]|κπάγλως ἀκάχησεν ἐ[πὶ ἐ]ῶνος ἀμέρθη·

8 αὐτὸς δ’ ἀχνύμενος τήνδ’ ἰστήλη[ν] ἀνέθηκεν·

9 τοὔνομα δὲ̣ [πό]σιος Φρόντων φ[ρεσβύ]τερός τε

μνήμης χ[άριν]

Here lies the prudent spouse of an influential and sagacious man, by the name of Venavia; [she was] attractive to look at; and her face was charming and endearing, whilst her eyes were like those of a cow. But after a short time she died. She went to Hades, leaving sunlight behind. She has caused terrible grief to her small child, and also to her best husband, having been taken from them forever. In sorrow he [sc. her husband] set up this tombstone; the husband’s name is Phronton, a presbyter;

in remembrance. (trans. adapted from Breytenbach, Zimmermann, 369)

The author of this epitaph used quite a few traditional pagan elements, of a sort which are ubiquitous even in the earliest Greek tomb inscriptions. His adoption of poetic conventions did not prevent him from inscribing a simple, unadorned phrase at the end, in remembrance, which is typical of short prose epitaphs, and is attested from the dawn of Greek culture.

Typical epitaphic features here include the name of the deceased, an indication of who she was, and also the initial declaration that the inscription is in the burial place. This epitaph matrix has been supplemented – as is usual in the case of inscriptions in honour of prematurely deceased wives and mothers – with relatively elaborate information about the woman’s beauty, constituting a kind of reverse tricolon crescens (beauty in general – face – eyes). Then there are the references to her husband and child, as well as their immeasurable grief.

What is striking is the extensive Homerising in the portrayal of the deceased wife and her husband. Venavia is defined as πινυτή (pinutē), prudent. Although this epithet appears in poetic funeral inscriptions for women, generally indicating their prudence or wisdom, here it seems to take on a special meaning in view of a very similar term describing Venavia’s spouse, i.e. πινυτόφρων (pinutophrōn), prudent-souled. Calling Venavia πινυτή must bring to readers’ minds the famous phrases from the Odyssey describing Penelope: πινυτή περ ἐοῦσα (Od. 21.103; 23.361) and λίην… πινυτή… περίφρων (Od. 11.445-446). In turn, naming Phronton πινυτόφρων must have evoked associations with Odysseus’ epithet in poetry of the Imperial Period, attested both in Quintus of Smyrna (14.630) and in the Cyzicene epigram (A.P. 3.38) there is a genitive (as here) Ὀδυσσῆος πινυτόφρονος.

It seems that both these epithets, πινυτή and πινυτόφρων, emphatically confer upon Venavia and Phronton the virtues with which the archetypal mythological couple known from the archaic Greek epic poem were endowed. Understandably, it seems, πινυτή and πινυτόφρων are not the only epithets applied to them. Phronton is described with two further adjectives: κρατερός (krateros,strong) and ἀριστῆος (aristēos, best). In Homeric terms, these emphasise one’s importance and prestige as a member of the community. These very qualities are reinforced here by the use of the noun φρεσβύτερος (phresbuteros) to indicate Phronton’s status and role within local society.

The description of Venavia is also highly Homeric. Her eyes are very specifically likened to those of a cow: ὄμματ(α) δ’ ὥστε βοός. This obvious allusion to the famous Homeric phrase: βοῶπις πότνια Ἥρη (e.g. Il. 1.554, 568, 4.50, 14.153, 18.239) emphasises her charming appearance, previously indicated by general expressions ἶδος ἔχ̣̣ουσα and χαρίεν κὲ ἐράσμιον ἦτο πρόσωπον. Regardless of whether the epithet referred to the shape or colour of the eyes, it was part of a purely aesthetic code defining the ideal of female beauty.

In this stylistically Homerising epithaph, calling Venavia a wife whose eyes were like those of a cow must have evoked associations with the traditional formula describing Hera, in the case of whom this epithet (often in conjunction with potnia) presented the goddess in her role of spouse.[6]

If we assume that the mention here of Venavia’s heifer-like eyes evokes associations with Hera, it is tempting to consider the hypothesis that the iconographic aspect of the stele may have been inspired by this image. Of course, it must be remembered that, in both pagan and Christian imagery, the peacock was commonly used as a symbol of immortality or an emblem of everlasting life, and widely used in sepulchral art as well as in Christian images of paradise. But peacocks with eye-spotted ‘tails’ were birds traditionally dedicated to Hera. These star-like ornaments on a peacock’s ‘tail’, which were mythologically associated with Hera’s transference of Argus’ hundred eyes to that part of the peacock, often appeared in art, but only on account of their intrinsic beauty, not because of any deeper symbolic significance.

It cannot be ruled out that the peacocks facing each other above the inscription correspond in some way to the verbal phrase associated with the goddess Hera in the Iliad.

The other two Christian epitaphs from the same area around Dedeler are perhaps not as sophisticated as the one commemorating Venavia, at least in terms of Homeric echoes. Nevertheless, they testify to the importance of Homer in the education not only of those who might compose epigrams but also of those who might read them. One praises the deceased priest Varelianus (this is the rare form of the name, instead of the expected ‘Valerianus’). Only the placement of a Greek cross at the beginning of the first line, and the name of his son-in-law, Aphthonius (a name meaning “without envy”, popular name among Lycaonian Christians), indicate that he was a Christian priest. The entire epigram is characterised by the use of traditional epitaph phrases (ICG 97):

1 + ἀνέρα κυδάλιμον ἀγανόφρονος ἠδ’ ἀγαθοῖο

2 ὀλβίου πατέρος γαίης τ’ ἐριβώλου ἀρούρης

3 σῆμα τόδε κεύθι φιλίῃ ἐνὶ πατρίδι γαίῃ

4 Οὐαρελιανὸν κλυτὸν ἄνδρα βροτῶν ἀγαθῶν τε τοκήων,

5 εἱερέων ὄχ’ ἄριστον ἑῆς ἐνὶ πατρίδι γαίῃ·

6 τούνεκά οἱ τόδε σῆμα ἑὴ θυγάτηρ καὶ ἄκοιτις

7 ἔστησαν μνήμης ἐπιτύμβιον ἐκτελέσαντες·

8 γαμβρὸς δ’ ἤτοι πάντα τελεσσάτο ἢ τάχ’ ἅπαντες.

9 Ἀφθόνιος ᾧ τοκέει γλυκερῷ ἀμοιβῆς δῶρα τελέσ||σας.

This monument in the beloved homeland conceals an honourable man, of a gentle-minded, good and happy father, and from a region with fertile farmland: Varelianus, a famous man among mortals, and of good parents, by far the best amongst the priests in his homeland. Therefore this memorial was erected by his daughter and his wife, as they made ready his tomb. The son-in-law should complete everything rapidly, or all together. Aphthonius completed this in thanksgiving for his dear father. (trans. Breytenbach, Zimmermann, 369–70)

As the genre expects, this epigram contains a lot of information about the deceased and his family. However, something else seems to be important. Varelianus is called κλυτὸς ἀνήρ, a glorious man, and εἱερέων ὄχ’ ἄριστος, the best of priests. These terms vividly resemble the famous Iliadic theme – being the best among all others,bringing undying glory (κλέος ἄφθιτον) to the whoever earns it. In the second book of the Iliad, the poet addresses the Muse and asks her to answer a question concerning the Danaans:

τίς τ’ ὰρ τῶν ὄχ᾽ ἄριστος ἔην σύ μοι ἔννεπε Μοῦσα (Il. 2.761)

Who was far the best among them, do tell me, Muse.

This idea is expressed using different variations of the same formula: ὃς μέγ᾽ ἄριστος Ἀχαιῶν εὔχεται εἶναι (Il. 2.82: who declares himself to be far the mighties of the Achaeans) or ὃς νῦν πολλὸν ἄριστος Ἀχαιῶν εὔχεται εἶναι (Il. 1.91: who now claims to be by far the best of the Achaeans). Those who had read the Iliad knew that this title was the object of fierce competition. Once the title is secured, it will ensure fame that will never perish. Calling the deceased Varelianus, the best of priests, just as the author of the Iliad presents Achilles as the best of the Achaeans,[7] must have been understood by those who read Homer at school as a clear sign of near-heroisation of Varelianus, who was manifestly an important figure for the local Christian community.

This Homeric way of honouring priests must have become a standardised description. We have confirmation of this in inscriptional material from Galatia,[8] for example where Sabinus the presbyter is commemorated as Σαβεῖνος ὄχ’ ἄριστος Χρειστοῦ ἱερεὺς μεγάλοιο (‘the best priest of the great Christ’).

The third verse inscription is written on a votive tablet with handles, a so-called tabula ansata, and honours the young athlete Apollinaris, probably a Christian from Axylon, as evidenced by his father’s name, Paul.[9] This epitaph was composed using phrases commonly known from Homer’s poems (ICG 107):

1 ἐνθάδ’ ἀνὴρ κρατερὸς κεῖτ’ ἐν χθονὶ πουλυβοτείρῃ,

2 τοὔνομα Ἀπολινάρις υἱὸς Παύλου, ὁπλότατος δ’ ἦν

3 ὧν τε κασιγνήτων, πρῶτος αὐτὸς ἐτελεύτα.

4 τοῦ δ’ ἰσχὺς μεγάλη, ἔργοισι δὲ πάντας <ἐν>είκα

5 ἐν πάτρῃ· οὐδὶς γὰρ ἐδύνατο τούτου ἐρίζειν

6 ἦν γὰρ ἀνείκητος, ὀλιγοχρ|όνειος δ’ ἐτελεύτα.

7 τύμβον δ’ ἀνέστησεν κασίγνητός τ’ υἱός τε

8 Κατμαρος καὶ Παῦλος μνήμης χάριν ἐξ ὄνομ’ ἕντες.

Here lies in the much-nourishing ground a mighty man, Apollinaris by name, youngest son of Paulus, and (youngest) of (his) marvelous brothers; but he died first. His strength was great and he defeated all in his homeland in (athletic) feasts; for no one was able to contend with this (man), since he was unconquerable; but he died short-lived; and his brother and son, Katmaros and Paulus, erected this tomb in his memory, setting forth his name/fame. (trans. from Breytenbach, Zimmermann, 81)

Right at the beginning, we find a phrase that closely refers to Homer’s notorious way of describing the earth. It is πουλυβοτείρη (poluboteirē), which literally means much– or all-nourishing, that is, ‘abundant’, or ‘bounteous’. As in Homer it is here used as a purely decorative device, an epithet that could certainly be omitted without loss of intelligibility. What is more, its literal meaning does not necessarily reflect the actual characteristic of the object to which it refers. The land in Axylon was not fertile at all (with some exceptions round Iconium), just as there is no indication that the ground upon which the Trojans and the Achaeans laid aside their battle gear (Il. 3.89) or upon which they stepped forth from the chariot (Il. 3.265) was plentiful or fertile.

The use of the epithet adds poetic beauty to the style, and makes it easier to fill (and memorise) the verse. The imitation by artists of a Late-Antique rural community of forms that in Homer’s time were characteristic of oral composition testifies to their familiarity with Homeric epic that must have been part of daily school reading. This is also evidenced by other adaptations of Homeric phraseology, such as the praise of Apollinaris’ excellence in line 4 (ἔργοισι δὲ πάντας <ἐν>είκα), which recalls the Iliadic description of Priam’s son, Polydorus (20.410: πόδεσσι δὲ πάντας ἐνίκα, ‘he surpassed all in swiftness of foot’).

Those who claim that knowledge of ancient literature, especially Homer, was central for people of late antiquity who sought to identify with high-status Greek or Roman socio-cultural groups living in large urban centres, are undoubtedly right. But it is also worth bearing in mind that this knowledge, confirmed by epigraphic monuments, attests to the diffusion of Classical paideia in the East of the Roman Empire, even in rather provincial contexts. In the countryside, saxa loquuntur (“the stones speak’)[10] exceptionally loudly. We can easily discover that Homeric resonances in inscriptions from small towns and villages are transparent, and apply also to Christianity. As Gianfranco Agosti diagnosed:

Religious confession has no significant consequences on literary production from a formal point of view: Christian and pagan poetry use the same language and the same erudite apparatus.[11]

Krystyna Bartol is Professor at the Institute of Classical Philology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań; she writes on Greek poetry, especially lyric, and Greek Imperial prose. She is currently working on minor genres of late Greek poetry. In the coming months, Brill will publish a collective volume co-edited by her and Jerzy Danielewicz, The Dynamic Quality of Late Greek Non-Christian Poetry: Studies in Minor Genres. She has previously written for Antigone about Greek attitudes to music here, Athenaeus’ Deipnosophists here, and Oppian’s Halieutica here.

Further Reading

There is an excellent study on the Christianisation of Lycaonia in the first five centuries AD. In the book Early Christianity in Lycaonia and Adjacent Areas: From Paul to Amphilochius of Iconium (E.J. Brill. Leiden, 2018), over nearly a thousand pages, Cilliers Breytenbach and Christiane Zimmerman weave a thoroughly documented narrative of the cultural history of this region. For them, verse inscriptions are an important source of knowledge on this subject. A significant contribution to the interpretation of the fascinating poetic works of Homerising artists from the Axylon region is Peter Thonemann’s “Poets of the Axylon”, Chiron 44 (2014) 191–232. To learn more about the oldest Greek epitaphic poetry and to follow how it was transformed in Late Antiquity, it is worth taking a look at Richard Hunter’s Greek Epitaphic Poetry: A Selection (Cambridge UP, 2022). And for those who want to test their Italian, I recommend the valuable works of Gianfranco Agosti, for example “Paideia classica e fede religiosa: annotazioni sul linguaggio dei carmi epigrafici tardoantichi,” Cahiers Glotz 21 (2010) 329–35.

Notes

| ⇧1 | For more about Mickiewicz, see this article. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | In Polish: O, gdybym kiedy dożył tej pociechy, /Żeby te księgi zbłądziły pod strzechy. |

| ⇧3 | The poet illustrates the point by adding: Where country girls with nimble fingers rove / The spinning wheel and sing the songs they love. |

| ⇧4 | It is not certain why it was so named. Strabo maintains that the area where it lies had been dried out by volcanic fumes. It is possible, however, that the name refers to the steppe climate. Or perhaps, as some believe, the town burned down at some point in the distant past. We should be careful not to mistake this city for another Laodicea on the river Lycus (modern Denizli on the Çürüksu). This is an entirely different city in Asia Minor, and is mentioned as the location of one of the seven churches in Asia in the Book of Revelation (Apocalypse). |

| ⇧5 | P. Thonemann, “Poets of the Axylon,” Chiron 44 (2014) 193. |

| ⇧6 | On this topic see V. Pirenne-Delforge & G. Pironi, The Hera of Zeus. Intimate Enemy, Ultimate Spouse (Cambridge UP, 2022) 15. |

| ⇧7 | This topic was extensively discussed by Gregory Nagy in his book The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry (John Hopkins UP, Baltimore, MD, 1979). |

| ⇧8 | SGO (3) 15/02/13. |

| ⇧9 | There are also other inscriptions confirming that numerous Lycaonian Christians were named after Paul the Apostle. |

| ⇧10 | This phrase, which has Biblical origins and has become, partly due to Sigmund Freud, a modern cultural maxim, was used by Gianfranco Agosti in the title of his important article devoted to the epigraphic tradition of the imperial East: “Saxa loquuntur? Epigrammi epigrafici e diffusione della Paideia nell’Oriente tardoantico,” AnTard. 18 (2010) 163–80. See also an extremely interesting study written by Branca Migotti, Saxa loquuntur: Roman Epitaphs from North-Western Croatia (Oxford UP, 2017). |

| ⇧11 | Agosti, op.cit, 164: “La confesione religiosa non ha conseguenze significative sulla produzione letteraria dal punto di vista formale: la poesia cristiana e quella pagana usano lo stesso linguaggio e lo stesso apparato erudito.” |