Nicholas Stone

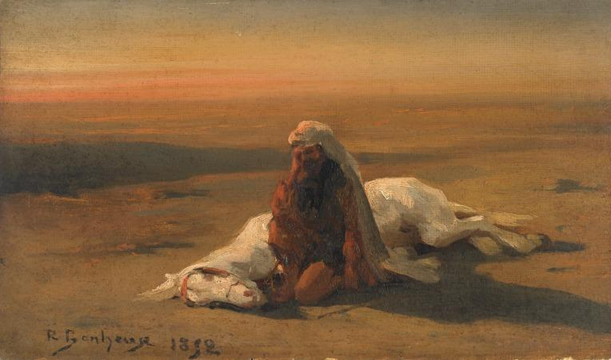

Suppose, as you are going about your business in Ancient Rome, you decide you want to buy a horse. “Nay bother,” you might say, “I see that man Aulus over there is selling a horse: I’ll give him some money, take the reins, and that’ll be that.” Seems simple enough. But hold your horses. How would you know that you had bought the horse? How, for that matter, would you know that you had bought anything? What would you need to prove if there were a dispute? What if you wanted to pay today and take the horse tomorrow, or vice versa? What happens if you blithely hand over your money thinking the horse is a fine stallion, but crafty old Aulus knows it’s a bag of bones ready for the knackers’ yard?[1]

The potential for things to go wrong is great even in a transaction as simple as exchanging money for a horse (or exchanging money for the right to receive ownership of a horse). It is easy to imagine how much more complicated things can become if you want to have a society with the potential for more sophisticated arrangements that would allow you to take out a loan, or deposit money in the bank, or hire people to build your house, or charter a ship.

This is where Law comes in. If you want to do anything more sociable than live by your wits alone on a desert island, then living in a world consisting only of physical objects is no longer enough: you also require abstractions, concepts and institutions. If we want a world in which we can buy and sell horses or charter ships, then we need rules, and shared understandings between people of what those rules mean, and the things to which they pertain, and perhaps mechanisms to enforce them.

We are all familiar with the most dramatic manifestations of law: the police officer leading away a suspected criminal in handcuffs exemplifies the power of the state to use force as authorised by some source of law. But most of the time, we interact with law in a much less dramatic way. Whenever you go to the shop to buy a chocolate bar, or go to see a show, or leave something to your friend in your will, you are using the law. We can call the law that concerns what the state must, can or can’t do (whether as a matter of addressing crime or otherwise) public law, and the law that concerns relationships between individuals private law.[2]

Rome was far from unique among ancient societies in having an extensive set of laws that we can still read today. To take only a few examples, one might consider the laws of the Hebrew Bible, of Hammurabi in Babylon, or of the Hittites in Anatolia. But Rome was unusual in the nature, scale and sophistication of its private law. Rather than having laws to regulate conduct between individuals expressed only through legislation by the state (though Rome had this as well, broadly called lex, i.e. “statute law”), it also had law that was understood to exist without having required any act of legislation to make it the law (called ius), but which required clarification by those learned in law when it was in doubt. It is arguably through the intricacy of this autonomously existing private law, and the methods by which their substantive law and system of private law were developed, that the Romans made their chief contribution to the intellectual heritage of humanity.[3]

That word system is worth dwelling on briefly. It is one thing merely to have a number of rules, given the authority of law by a state, and expect (or force) people to obey them. It is another thing for those rules to be organised according to rational principles, such that the underlying principles of the body of law might become clear, and so that in turn it may be possible to infer from rules that are already known to exist what the law must be in a novel situation. The idea that law might be an autonomous intellectual discipline, generative of its own solutions by reference to its own premises, was a discovery that reshaped the course of human conduct. Arguably it is a discovery that we owe to Rome.[4]

This realisation that law could provide answers to questions by using reasoning, rather than by authority alone, has profound implications not just for the sophistication of law, but for the idea of what we might call rights. If it is possible to work out that something must be the law (in a given case, perhaps as to what is due to us)[5] by reasoning from premises of things we already recognise as law, then it is possible to identify “law not simply positive [i.e. declared by an authority], but existing of right and coordinated and developed by reason.”[6] And further, if what is lawfully due to us can be identified by a process of rational argument based on the nature of things (known laws being among those things but not exhausting them), then it might be possible to say that we have natural rights, and that we might have those rights whether or not there is any legislation that declares we have them. It is ironic that a society that engaged pervasively in slavery nevertheless developed a conceptual apparatus that now offers perhaps the most powerful basis for defending universal human dignity.

“That is all very well,” you might say, “but where did that Roman addiction to legal reasoning come from? What did it look like in practice? And what about my horse?” Fair questions all.

Roman law was not always an intellectual wonder. In the beginning (Rome was founded in 753 BC), we have very little idea what it was like. By some early stage, the answers to questions of doubtful law were decided on the authority of the priests. The bases on which the priests arrived at their answers were shrouded in mystery. In 509 BC, the Roman monarchy fell, and was replaced by a Republic, at around the same time that the constitutions of various Greek city-states were being radically reformed in a more democratic direction (e.g. the Athenians expelled their tyrants in 510 BC). Not long after (traditionally, 451–450 BC), the change of constitution from arbitrary rule by kings was followed by a change in the fundamental conditions of access to justice: the common people of Rome demanded that their laws be set in writing rather than applied capriciously by aristocratic office-holders and determined mysteriously by aristocratic priests,[7] and displayed where they could see them – and thus the Twelve Tables came to be.

We do not know exactly what laws these Tables contained; they seem to have been particularly concerned with giving a fair expectation of what procedures were to be followed in litigation, as well as issues that would have been likely to arise often in a more primitive agricultural society. They were far from a complete code of law, but crucially the settlement of disputes was no longer such a mystery. It seems significant that the transition away from arbitrary government by a tyrant occurred not long before the demand for written law, and that inspiration was supposedly taken from the (proto-)democratic movements of Greek city states towards written laws.[8] It may be a very old piece of common sense that a fundamental part of living under the rule of law is being able to know what the law is.

The Twelve Tables were not the end of the story. Problems inevitably arose to which the plain wording of the Tables did not offer clear answers, or which their laws simply did not address. And you cannot pass new legislation through your magistrates and assemblies to settle the issue every time people have a dispute: they need to know what the law already is. The priests’ authority to answer such questions continued and their reasoning remained mysterious. In response to this problem, a new type of person gradually emerged: the jurist. The development of a class of jurists behaving identifiably differently from the priests seems to have begun in earnest with a certain chief priest in the mid 3rd-century, the first chief priest to be of plebeian origin, Tiberius Coruncanius, who began to discuss law publicly rather than only amongst other priests and scholars, and to offer himself to those who wanted to learn.[9]

Jurists, who as time went on were increasingly less likely to be priests themselves, became a cross between legal academics, legal consultants and public servants, working without payment. They did not argue cases in court, leaving that less prestigious task to dedicated advocates; instead, they advised as to what the answers to legal problems were. As the late Repulican jurist Aquilius Gallus replied in response to questions where the facts of the case were at issue, “nihil hoc ad ius; ad Ciceronem”: “This has nothing to do with law. Ask Cicero.”[10]

By the latter centuries of the Republic, jurists were putting their thoughts about legal problems in writing, and criticising each other’s writings. Unlike the priests, jurists’ answers could be interrogated: they were only as good as either the jurist’s reasoning, or his authority – and a jurist’s authority ultimately rested on whether people thought well of his ability to arrive at good answers.[11] Under the influence of Greek philosophy, jurists began not merely explaining the law but categorising and systematising it. Rather than mapping the law only incrementally and casuistically, by considering the differences and similarities between different individual factual cases, the jurists now also began to consider what linked entire categories of legal situations and concepts from first principles. Rival schools of legal learning grew up, called the Sabinians and the Proculians, after the great jurists Sabinus and Proculus respectively. What exactly the differences were between their approaches to law remains a subject of scholarly enquiry.

The growth of the class of jurists and advances in the techniques of legal thought in the second half of the Republican period were particularly stimulated by innovations in legal procedure. It was always the case that at the first stage of litigation, litigants would go before an official and state their case. If this revealed that there was a triable case (i.e. a claim that the law recognised it could potentially remedy), it could then proceed to a trial on the factual issue, in which that official would not be involved, but rather a judge who was an ordinary private citizen of good repute. Originally, stating their case had required the litigants to recite the precise words of a limited number of established forms, almost like magic spells. This system was known as legis actio (action according to law). In one case, a man was unable to bring an action because he had used the word “vines” rather than the prescribed word “trees”, even though the case could otherwise have been heard.[12]

Sometime in the late 3rd or 2nd century, the old procedure was superseded by one called the formulary system. In 367 BC the office of the praetor had been instituted, to take over from the consuls the responsibility for the administration of justice. Originally, there had been only one, but as Rome came to have an increasing number of non-Roman foreigners, or “peregrines,” to whom the legal forms peculiar to the Roman people, the ius civile, did not apply, in 242 BC another praetor was created to address their legal issues. The praetor for Romans was therefore called the urban praetor and the one for foreigners the peregrine praetor. The peregrine praetor got round the inapplicability of civil law answers to peregrines’ problems by using the power inherent in his office to provide remedies where the existing civil law didn’t offer them. A body of law grew up called the ius honorarium (“honorary law,” so called to distinguish it from pre-existing civil law by denoting that it derived from the “honorary” office of the praetors, or other officials like the aediles, who exercised similar power over the markets).

This created a situation where more flexible legal solutions were available to peregrines than to Romans, and so the honorary system was adopted to supplement the civil law for Romans also.[13] The new system that the praetors developed retained the division between the statement of case in front of an official before the trial of fact in front of a layman. But instead of requiring a strict recitation of set phrases, the praetor questioned the parties as to the points at issue between them, and devised a formula that could be written down and handed under seal to the lay judge to show him how to decide the case depending on what facts he found.[14]

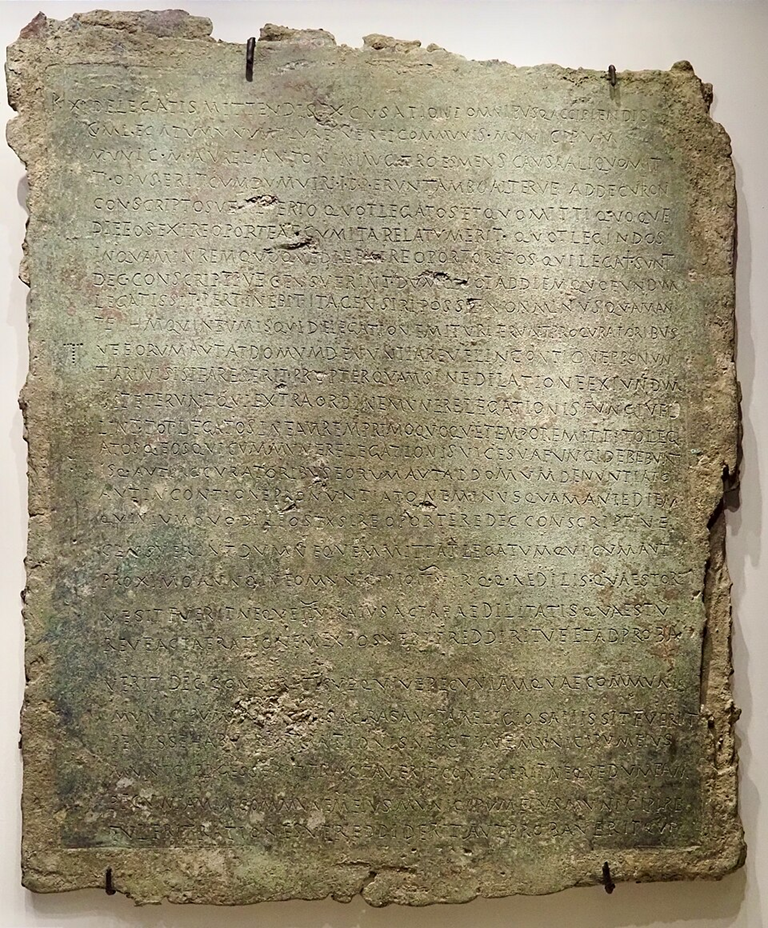

Because of the praetors’ inherent power as the administrators of justice, they were not confined merely to stating their formulas based on the law as it already was, but could supplement it with formulas that protected the rights of litigants where the law as it stood did not meet the needs of the case: [15] the ius honorarium was able to fulfil the spirit of the ius civile where its letter was lacking, “for indeed the ius honorarium itself [was] the living voice of the ius civile.”[16] Praetors would produce an Edict each year, stating what remedies they would permit, which would be set up on white-painted boards in the forum. This supplementary system to the civil law provided a powerful new source of legal development.

Advising praetors and litigants on what were effectively reforms to the substantive law, without either injuring its coherence or undermining confidence in it, surely provided jurists with much fruitful work and stimulus to thought, until Hadrian abolished this praetorian responsibility (AD 129) and had a final Edict produced to be used in perpetuity.[17]

By the height of the Imperial period, jurists had developed an extremely sophisticated and extensive body of law quite independent of legislation which was perpetually subjected to refinements based on its own internal logic: the law was in quest of itself.[18] To be a great jurist offered a path to great power in the state, as well as great danger. One might become a senior figure in the imperial bureaucracy, and author answers to legal questions in the name of the emperor himself, while exercising considerable political influence to boot; one might also get murdered in political intrigues. Two of the greatest jurists, Papinian (d. AD 212) and Ulpian (d. AD 228), rose to the office of praetorian prefect, the emperor’s chief legal official and chief of staff, only to be killed in power struggles in the uneasy years leading up to the crisis of the 3rd century (a period of fifty years, 235–85, when emperors came and went with the seasons).

In the centuries that followed this crisis, the empire split between East and West, and the law fell into a state of neglect. The political, material and cultural conditions to sustain high-level juristic endeavour fell away, and bastardised law books containing simplified sayings attributed to the Classical jurists circulated in the West. “The social upheavals of the time were such that clever men preferred to contemplate the heavenly city than the earthly city.”[19] To try and set a baseline for the quality of legal sources, the seven-year old emperor Valentinian III instituted a Law of Citations in AD 426, restricting practitioners to citing only the texts of five specified (long-dead) jurists, with an algorithmic procedure for how to arrive at an answer when they disagreed.

Then, in the 6th century, everything changed. Justinian (r. AD 527–65) was a man on several missions: to expand from his base in Byzantium to reconquer the Western empire that had now fallen to the Goths; to forge an empire fit for the Christian God; to restore the utility and elegance of Roman law to their Classical height.[20] Whether he successfully made a holy empire is best left to theologians. He did succeed in reconquering Italy, and in orchestrating an astonishing revival of Roman law.

To have a coherent, unified legal text that could be used in court anywhere throughout his great empire, he commissioned a team of scholars to comb through the jurists’ disparate writings and produce a single body of texts that authoritatively stated what the law really was. The resultant Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law) is a work roughly three times the length of the Bible, comprising the Codex (a collection of legislative enactments), the Digest (a compendium of passages extracted from the jurists), the Institutes (an elementary textbook on the law, itself given the status of legal authority) and the Novels (a collection of Justinian’s own later legislation). Justinian boasted that this new codified law contained no contradictions that a subtle mind could not reconcile.[21] Many law students over the next millennium and a half have had serious doubts about this in the small hours. But the concept of a complete and perfect code revived the notion of law in quest of itself, in a sense: the premises from which reason might deduce right were now all there in the books, if one only looked hard enough.

With the exception of the Institutes of Gaius (an influential elementary textbook by a mysterious 2nd-century AD jurist, and the model for Justinian’s Institutes) and some fragments, all that we now have of the jurists, we have from Justinian’s Digest. The subsequent history of European law is a series of reactions to the rediscovery of the Digest in somewhere around Bologna in the late 11th century. That is a tale too long to be told here. Here, it must suffice to note that every day, billions of people now use law that is based either directly on the rules and concepts of Roman law preserved by Justinian or indirectly derived from the structural principles of his codification.

“That is all very well,” I hear you say again, patiently, “but what about my horse?! I have places to go!” Fear not. Please turn to the following texts, and you can work out how to go about your purchase:

- Justinian’s Institutes 3.13, 3.22, 3.23.

- Digest: on sale and purchase generally, Books 18 and the first Title of 19 explain and expand on Institutes 3.23 and its ramifications across a wide range of scenarios; on issues of purchases with latent defects, consider the following sections of Book 21: 21.1.1.pr, 21.1.1.6-8, 21.1.38, 21.1.63.[22]

Nicholas Stone has written for Antigone about rhythm in Latin poetry, and has published various Latin poems, which can be found here, here, here, here, and here.

Further Reading

The texts:

The best possible way into Roman law is to read Roman law. A parallel-text edition of the Institutes of Gaius, with English translation by W.M. Gordon and O.F. Robinson, is available from Duckworth (London, 1988). Duckworth also supplies a parallel text edition of the Institutes of Justinian (London, 1987), by Peter Birks and Grant McLeod, and it is useful to read it alongside Gaius. After looking at Gaius’ and Justinian’s respective Institutes, try Justinian’s Digest. For preference, use the edition with Latin text edited by Mommsen and Krueger and English translation edited by Alan Watson (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, 1985). Although it is the best available, Watson’s translation was an enormous project conducted by many hands and its results are not faultless or uncontroversial in all cases – so keep an eye on the Latin, if you’ve studied it. It is also very expensive, if you can’t access it online. In any case where you can’t get hold of a more authoritative edition, the texts available at the following sites will be useful to consult as a stop-gap (but note that the readily available English translation by Scott, hyperlinked above and below, is not as reliable as Watson’s):

Textbooks:

An Introduction to Roman Private Law by Barry Nicholas is probably the most helpful book for initial explorations, especially for people beginning Roman law as students of English law, but it sacrifices complexity (and citations) for the sake of clarity. The most recent edition (Oxford UP, 2008) also contains a useful glossary of Roman legal terms by Ernest Metzger. Many other introductory books are available (with their own inevitable trade-offs). Three that are particularly helpful are Rafael Domingo’s Roman Law: An Introduction (Routledge, London, 2018), Paul J. Du Plessis’ Borkowski’s Textbook of Roman Law (6th ed. Oxford UP, 2020) and Hans Julius Wolff’s Roman Law: An Historical Introduction (Oklahoma UP, Norman, OK, 1951).

For more detailed study, consult Classical Roman Law by Fritz Schulz (Oxford UP, 1951) and the Textbook of Roman Law from Augustus to Justinian by W.W. Buckland (3rd ed., Cambridge UP, 1951).[23] Likewise, Adolf Berger’s Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (Transactions of the American Philological Society, Philadelphia, PA, 1953).

Practice and Context:

J.A. Crook’s Legal Advocacy in the Roman World (Duckworth, London, 1995) offers a useful corrective to thinking about law primarily as something that exists in books; Crook’s Law and Life of Rome (Cornell UP, Ithaca, NY, 1967) is a wonderfully written (and more general and accessible) view of how things looked in the real world. Another very useful work doing what it says on the tin is David Johnston’s Roman Law in Context (2nd ed., Cambridge UP, 2022).

From beginning to end:

Wolfgang Kunkel’s An Introduction to Roman Legal and Constitutional History, translated from German by J.M. Kelly (2nd ed., Oxford UP, 1972), is a very useful (and short) explanation of the development of the law in its historical context. If you want to explore these issues in more detail, The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law, ed. David Johnston (Cambridge UP, 2015) covers a lot of ground, as does Jolowicz and Nicholas’ Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law (Cambridge UP, 1972). Roman Law Before the Twelve Tables, edd. Bell and Du Plessis (Edinburgh UP, 2020) gives good reasons to question everything I have said about early Roman law, from many different directions.

Historical background for the two main periods from which we have sources for Roman private law can be found in David Potter’s The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395 (2nd ed., Routledge, London, 2014,) and Peter Sarris’ Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint (Hachette, London, 2023).

The influence of Roman law on the later history of the world is an enormous topic, partly because it is still going on. Several chapters of the Cambridge Companion offer a good starting point. Other works worth exploring include Tamar Herzog’s A Short History of European Law: The Last Two and a Half Millenia (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2018) and especially Peter Stein’s Roman Law in European History (Cambridge UP, 1999).

Women:

The position of women in Roman law is a huge topic. The texts and textbooks cited above all deal with many issues pertaining specifically to women. Excellent books to follow up are Jane Gardner’s Women in Roman Law and Society (Indiana UP, Bloomington, IN, 1986) and Susan Treggiari’s Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian (Oxford UP, 1991).

Slavery:

Much Roman law concerns slavery. Jerry Toner’s translation of Marcus Sidonius Falx’s treatise How to Manage Your Slaves (Profile Books, London, 2014) is an excellent guide to the lives of slaves and their owners in Rome and the key historical sources. Buckland’s book The Roman Law of Slavery (Cambridge UP, 1908) remains useful. Jane Gardner’s chapter on Roman Law in the Cambridge World History of Slavery (Vol. 1, edd. K. Bradley and P. Cartledge, Cambridge UP, 2011) offers a good recent view.

Literature:

The broad relevance of Roman Law to Latin literature has not been studied as much as might have been desirable.[24] But Classical Latin authors would have been well-acquainted with their legal institutions, processes and language and many would have acted as judges from time to time.[25] A recent collection edited by Ioannis Ziogas and Erica M. Bexley makes useful contributions: Roman Law and Latin Literature (Bloomsbury, London, 2022).

Jurisprudence more generally:

I have opened various philosophical cans of worms in this essay and said things that require far more justification than would be helpful in this sort of introduction. If you would like to have a go at putting the worms back in their cans, then it is worth thinking about law per se rather than just Roman Law. To begin with, try H.L.A. Hart’s The Concept of Law (3rd ed., Oxford UP, 2012), John Finnis’s Natural Law and Natural Rights (2nd ed., Oxford UP, 2011) and Ronald Dworkin’s Law’s Empire (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 1986). Hart was an intellectual predecessor and sparring partner of both Finnis and Dworkin. The context of Hart’s own approach to the philosophy of law is explained by Nikhil Krishnan’s readable and entertaining book A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy at Oxford 1900-60. (Profile Books, London, 2023).

Notes

| ⇧1 | I am grateful to William Moppett for his comments on this article. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | A distinction we owe principally to the great Roman jurist Ulpian: Huius studii duae sunt positiones, publicum et privatum. publicum ius est quod ad statum rei romanae spectat, privatum quod ad singulorum utilitatem: sunt enim quaedam publice utilia, quaedam privatim. publicum ius in sacris, in sacerdotibus, in magistratibus constitit. privatum ius tripertitum est: collectum etenim est ex naturalibus praeceptis aut gentium aut civilibus. D.1.1.1.2. (“There are two branches of legal study: public and private law. Public law is that which concerns the constitution of the Roman state, private that which concerns individuals’ interests, some matters being of public and others of private interest. Public law covers religious affairs, the priesthood, and offices of state. Private law is tripartite, being derived from principles of natural law, the law of all peoples, or civil law.” Based on Watson’s translation, with amendments). |

| ⇧3 | “If [literature, philosophy and religion] were all, one might be disposed to conclude that Rome had left little of her own to the modern world of philosophic or even of ethical value. There is, however, one great and conspicuous exception – the legacy of Roman Law. This was the domain in which Rome showed constructive genius. She founded, developed, and systematized the jurisprudence of the world.” With these ringing words, Herbert Henry Asquith, former British Prime Minister (1908–16), concluded his introduction to a landmark collection of essays on the Roman contribution to civilisation: H.H. Asquith, “Introduction” in The Legacy of Rome, ed. C. Bailey (Oxford UP, 1924) 11. |

| ⇧4 | It is of course possible that transmission of the discovery and its consequences should have been principally due to the Roman tradition, without the Romans having been the only people to make such a discovery. There are very interesting parallels in the Jewish legal tradition, but that needs another essay. |

| ⇧5 | As Ulpian put it: iuris praecepta sunt haec: honeste vivere, alterum non laedere, suum cuique tribuere (“the fundamental points of law are these: to live honourably, not to harm another, and to give to each what is his”) D.1.1.10.1. |

| ⇧6 | Francis De Zulueta, “The Science of Law” in The Legacy of Rome, ed. C. Bailey (Oxford UP, 1924) 175. |

| ⇧7 | The consulship was open only to patricians until 367 BC; the priesthood until 300 BC. |

| ⇧8 | Livy, 3.31.8; D.1.2.2.1-4. |

| ⇧9 | D.1.2.2.35. |

| ⇧10 | Cicero, Topica 12[51]. |

| ⇧11 | From the time of Augustus (r. 27 BC–AD 14) onwards, various marks of official approval were also accorded to particular jurists. But whether most of these did anything more than give an imperial stamp to what was already generally acknowledged about a given jurist’s authority is less clear. In the post-Classical period, this changed – more on this below. |

| ⇧12 | Gai. Inst. 4.11. |

| ⇧13 | This is conjecture. The exact sequence and causation of events leading to the formulary system is unknown. See Jolowicz and Nicholas, Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law (Cambridge UP, 1972) 218–25. |

| ⇧14 | Gai. Inst. 4.29-30. To take a simple example of a formula (from Jolowicz and Nicholas, Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law (Cambridge UP, 1972) 200: “[Let Titius be judge.] If it appear that Numerius Negidius ought to pay ten thousand sesterces to Aulus Agerius, the judge is to condemn Numerius Negidius to pay Aulus Agerius ten thousand sesterces, if it does not appear he is to absolve[.]” The names Aulus Agerius and Numerius Negidius were conventionally used for such illustrations as puns on the roles of the parties: Agerius as a pun on agere (to bring an action), Negidius on negare (to deny it). |

| ⇧15 | D.1.1.7.1. |

| ⇧16 | Marcian, D.1.1.8. |

| ⇧17 | The formulary system too was eventually replaced under imperial rule by the cognitio procedure, in which there was only one stage, in which a professional judge dealt with issues of both fact and law at the same time. This is the original model for civil procedure in civil law countries today. |

| ⇧18 | A line I stole, to add some colour,

From law professor Lon L. Fuller. Lon L. Fuller, The Law in Quest of Itself, (The Foundation Press, Chicago, IL,1940). |

| ⇧19 | Peter Stein, Roman Law in European History (Cambridge UP, 1999) 25. |

| ⇧20 | Roman lawyers (or civilians, as they are called, after the ius civile) use the term “Classical” to refer to the period when Roman jurisprudence was at its best, i.e. between the beginning of the principate of Augustus in 27 BC and the start of the crisis of the 3rd century, whereas Classicists use it to refer to the period when Latin literature is generally thought to have been at its best, i.e. from the early-to-mid 1st century BC to the mid-to-late 1st century AD. |

| ⇧21 | Constitutio Tanta 15. |

| ⇧22 | Do not worry if, in the course of these researches, you encounter unfamiliar terms: go to Berger (below) and look them up. |

| ⇧23 | Though watch out when they start talking about interpolations in the ancient texts – scholars of the early-to-mid 20th century were quicker to view passages that seemed peculiar in their context as being derived from other sources. These days there is more caution about ascribing oddities to interpolations. |

| ⇧24 | “No classical scholar would deny that one of the greatest achievements of ancient society is the Roman law. Yet it can be said that nearly all classical scholars deliberately and systematically avoid any acquaintance with it…” Max Radin, “A glimpse of Roman Law”, The Classical Journal 45.2 (Nov. 1949) 71. |

| ⇧25 | Horace Epp. 1.16.40–3. |