Tom Jones

The murder of a celebrated political figure and media presence – one more in a troubling sequence of politically motivated assaults – sent a tremor through the American republic. In Utah, Matt Robinson joined the thousands examining the images released by the authorities in their pursuit of the man who had slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

The suspect, wearing a black T-shirt emblazoned with an eagle and American flag, was captured on camera leaping from the roof of a Utah Valley University building moments after the shooting, then disappearing into nearby woods. His face was partly hidden behind dark sunglasses and a baseball cap, but the father knew the man instantly. “Tyler, is this you?” he reportedly asked his son; “this looks like you.”

His son, 22-year-old Tyler Robinson, then admitted he had shot Kirk. His father urged him to turn himself in. “I would rather kill myself than turn myself in,” he replied.

His father pressed on, steering him toward a youth pastor he knew, who was tied to the Washington County Sheriff’s Office and the U.S. Marshals Service. Hours later, and just two hours after officials publicly pleaded for help, Robinson was in custody. It was 10 p.m. Thursday in Utah; only two hours earlier, state and federal officials had held a press conference appealing for the public’s help.

Robinson Sr handed in his son despite the fact that, if prosecutors secure a guilty verdict and seek the death penalty against him, he could face the firing squad. This is an act of dedication few of us could contemplate, and none hope to face.

By design, the American republic is an echo of the Roman. Robinson Sr’s actions should remind us that, even if the explicit fact may have faded from the conscious mind of the body politic, the implications for the meaning of civic virtue are still felt; centuries after the founding, and even among those who cannot name its source, the voice of history calls; steady, clear, unyielding.

* * *

Robinson Sr’s grim decision recalls an older exemplar who, at the dawn of the Roman Republic, set aside all private ties to safeguard the laws and liberty of his city. That man was Lucius Junius Brutus, whose name would be forever bound to the lictors’ rods and the unflinching justice they symbolised.

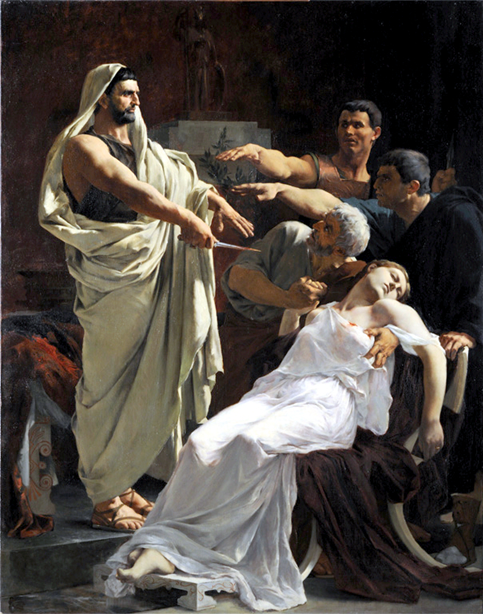

Lucius Junius Brutus, ancestor of the Caesar-slaying Brutus, is perhaps most famous now as the subject of Jacques-Louis David’s 1789 masterpiece The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons. David was history’s most extraordinary political propaganda painter and, as a founder figure in the Neoclassical movement, saw the myths and history of Rome as analogous to the contemporary politics of Republican France.

Like his earlier Oath of the Horatii, in Brutus David has alighted on an opportunity to elide the virtue of choice of political ideals over personal motives. In the right middleground and capturing the attention spectacularly, the women of Brutus’ family stand bathed in light. One of his daughters has fainted; the other shields her face with her hands. His wife stretches a pitiable hand to the doorway, through which is emerging, born by the lictors on a stretcher, the legs of one of his sons.

The other, almost imperceptibly disappearing into the darkening background, has already been taken in. Brutus sits silent in the shadowed foreground; apart, he has momentarily raised his head from being propped on his hand to stare into the middle distance in the exact opposite direction as his son’s bodies, his body held stiffly rigid atop a klismos, legs twisted in tension. It depicts a moment not reported by historians directly, but it matters little; the pathos transmits the ethos perfectly.

Brutus was a key figure in the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the establishment of the Republic in 509 BC. Half a millennium later, the historian Livy writes that as a young man Brutus, as the nephew of the last King, Tarquin (ruled 534–509), understood that he would need to distance himself from Tarquin’s regime, which he achieved by deliberately putting on “an act of being stupid”.

Brutus won divine favour through his shrewd reading of the oracle at Delphi. Travelling with Tarquin’s sons, Titus and Arruns, to seek counsel from the Pythia, he heard the prophecy: imperium summum Romae habebit, qui vestrum primus, o iuvenes, osculum matri tulerit, “whoever of you, young men, shall be the first to kiss his mother will hold the highest power in Rome” (Livy 1.56.10). While his companions took the words literally, Brutus grasped the oracle’s broader meaning. Feigning a stumble, he fell to the ground and kissed the earth, recognising her as “the shared mother of all mortals” (communis mater omnium mortalium, 1.56.12).

Chafing under Tarquin, a leader they had always hated, the Romans found that added exhaustion to their unhappy burden, through both the pace and scale of his building programme. Brutus’ moment to strike came in the wake of the rape of Lucretia; as Tribune of the Celeres, Brutus commanded the king’s personal bodyguard and held the authority to convene the comitia (public assemblies). By summoning the people, cataloguing the people’s grievances, denouncing the king’s abuses, and rousing outrage through the account of Lucretia’s rape, he convinced them to strip the king of his imperium and decree his exile. They were, as Livy reports, “moved not only by the father’s grief but also by Brutus, who reprimanded them for their tears and idle complaints, urging them, as befit men and Romans, to take up arms against those who had dared such acts of hostility.”[1]

Brutus, having overthrown Tarquin, is then made consul. Of a Republic, if he can keep it; Tarquin, fleeing into Etrurian exile, did not simply relinquish his power willingly. While he set about raising an army, envoys were dispatched to the Senate – ostensibly to petition for the restoration of his personal property, but in truth to win over and corrupt several of Rome’s foremost men.

The consuls, aware of the plot, seize both Tarquin’s ambassadors and the conspirators, in one fell swoop crushing the whole affair. Two of those conspirators are Brutus’ sons, Titus and Tiberius. The pitiable scene of their sentencing and punishment is related by Livy thus:

direptis bonis regum damnati proditores sumptumque supplicium, conspectius eo, quod poenae capiendae ministerium patri de liberis consulatus inposuit, et, qui spectator erat amovendus, eum ipsum fortuna exactorem supplicii dedit.

stabant deligati ad palum nobilissimi iuvenes; sed a ceteris, velut ab ignotis capitibus, consulis liberi omnium in se averterant oculos, miserebatque non poenae magis homines quam sceleris, quo poenam meriti essent.

illos eo potissimum anno patriam liberatam, patrem liberatorem, consulatum ortum ex domo Iunia, patres, plebem, quidquid deorum hominumque Romanorum esset, induxisse in animum, ut superbo quondam regi, tum infesto exuli proderent.

After plundering the tyrants’ effects, the traitors were condemned and capital punishment inflicted. Their punishment was the more remarkable, because the consulship imposed on the father the office of punishing his own children, and him who should have been removed as a spectator, fortune assigned as the person to exact the punishment.

Young men of the highest quality stood tied to a stake; but the consul’s sons attracted the eyes of all the spectators from the rest of the criminals, as from persons unknown; nor did the people pity them more on account of the severity of the punishment, than the horrid crime by which they had deserved it.

That they, in that year particularly, should have brought themselves to betray into the hands of Tarquin, formerly a proud tyrant, and now an exasperated exile, their country just delivered, their father its deliverer, the consulate which took its rise from the family of the Junii, the fathers, the people, and whatever belonged either to the gods or the citizens of Rome. (Livy 2.5.5–7)

* * *

By the time Robinson was apprehended, the FBI had received over 7,000 leads and tips – the most since the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013. Just hours before, however, authorities said they had “no idea” where the suspect was, and had put out an appeal to the public for information. He might never have escaped justice in the end, yet his father’s decision shortened, drastically, the time between crime and reckoning – and a grieving family’s wait for justice.

The choice Matt Robinson made, to deliver his own son into the hands of the law whilst knowing it could lead to his execution, is almost unbearable to imagine. We cannot imagine his decision – or that of Brutus – was an easy one, made by men of sterner stuff; Livy reports that during the execution “the father, his looks and his countenance, presented a touching spectacle, the feelings of the father bursting forth during the office of superintending the public execution.”[2] Robinson could not make the call himself.

Yet it is precisely in such moments, when private love collides with public duty, that the true weight of republican virtue is revealed. The Founding Fathers, steeped in their Livy, would have recognised that in the American tradition, as in the Roman, the republic survives only when its citizens place the law above blood, the common good above personal cost and the public principle over private preference. Demands for sacrifice of this scale are, thankfully, remarkable in their rareness, but if a people are without the will to place duty above self, then a republic is without that which makes it worth defending. Its heart beats only so long as there are citizens who will bleed for it.

As his son’s actions were despicable, in the actions of the father is found some small measure of redemption for both his name and his nation. The sun rises black and clouds gather foreboding in America. But whilst a republic can still call from the well of its public such acts of fidelity, it still has within it the virtue to save itself. As in the days of Brutus, so now: the life of the republic is secured by those who would sacrifice blood and bond for the safety of the state.

Tom Jones is a writer and Councillor for Scotton and Lower Wensleydale. He tweets at @93vintagejones and writes a substack, The Potemkin Village Idiot.

Notes

| ⇧1 | movet cum patris maestitia, tum Brutus castigator lacrimarum atque inertium querellarum auctorque quod viros, quod Romanos deceret, arma capiendi adversus hostilia ausos (Livy 1.59.4). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | pater vultusque et os eius spectaculo esset eminente animo patrio inter publicae poenae ministerium (Livy 2.5.8). |