A 1930s plea for intellectual curiosity

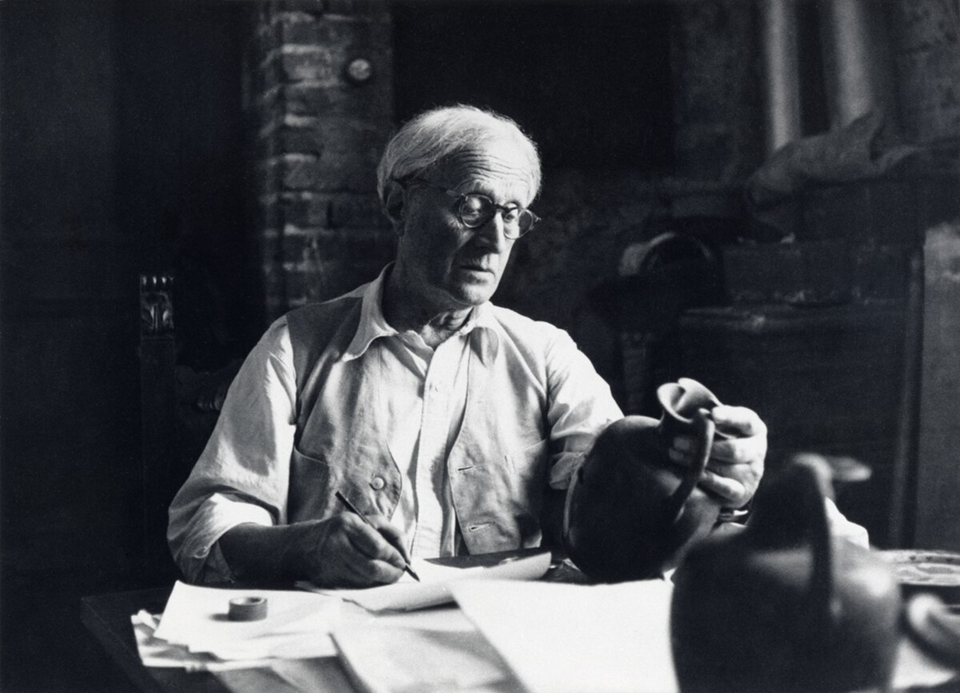

Campbell Bonner’s is not quite a household name, even to professional Classicists. In his day, he was well-known and respected, and not just in his home country. But he was not a populariser, and contented himself by toiling in obscure regions, where he judged that he could do the most good. The Classical scholar described in the following essay, vigorous and versatile, is in many ways a self-portrait.

Bonner was born in 1876, the son of a Tennessee judge. He was educated first at the recently-established Vanderbilt University, before heading north to the more venerable Harvard University for his PhD. This he earned in 1900, with a Latin dissertation on the myth of the Danaids (translated here). In it he demonstrated not only the expected linguistic mastery over a wide range of ancient texts, but also an interest in the new fields of anthropology and comparative religion. Frazer’s Golden Bough is cited, as is his commentary on Pausanias. Bonner’s “strange adventure of the mind” had begun.

After graduation Bonner spent a year in Berlin, where he heard Wilamowitz lecture, before visiting the Mediterranean. In Greece he sailed through the islands with Martin Nilsson, the great Swedish scholar of ancient religion. Returning to America, he took up a position at Peabody College in Nashville, Tennessee. He would hold this until 1907, when he was offered a job at the University of Michigan. Thereafter he spent the rest of his life in Ann Arbor.

The watershed in his career came in 1920, when the University of Michigan began acquiring Greek papyri from Egypt under the initiative of Francis Kelsey. This, as Bonner describes it, “diverted the energy of several men into new channels.” He was one of that number, though too modest here to name himself. His first papyrological publication appeared in 1921; the last in 1954, the year of his death. Among these were three major editions: The Papyrus Codex of the Shepherd of Hermas, The Last Chapters of Enoch in Greek, and The Homily on the Passion by Melito, Bishop of Sardis. Hardly household names either; but there was work to be done, and Bonner did it well. In such a way a man may build his reputation.

Today Bonner’s name is remembered chiefly in connection with ‘magical amulets’, carved gemstones engraved with magical incantations. He came to these artefacts through the study of magical papyri, and for over two decades both studied and collected them. After his retirement in 1944, he committed his final productive years to their study, producing the magisterial Studies in Magical Amulets in 1950. “Few subjects are more remote from the interests of most classical students,” his preface begins, and indeed even the following essay, written in 1935, does not seem to envision that these would be the strange companions of his final years. But his work gave these amulets their place in Classical scholarship, which is not easily done. Today, students of ancient gems work with the assistance of the Campbell Bonner Magical Gems Database.

Bonner received the highest professional honours that a Classicist in America could expect: he was president of the American Philological Association, fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a corresponding fellow of the British Academy, and a member of the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin in the days when America remained loyal. As a scholar he was prolific, versatile, and capable. The following essay, however, is not well-known. Printed in the Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review (vol. 42.1, 1935, 582–93), you will not find it listed in published bibliographies of his work. In making it available, Antigone continues its mission to explore what Classics has been and can be.

Bonner’s vision of the discipline shows the great influence of the scholars he met in Berlin. The Germans of the late 19th century conceived of a ‘Science of Antiquity’, Altertumswissenschaft, which incorporated new discoveries in archaeology, epigraphy, and papyrology into the traditional study of Classical texts. The ancient world was a unified whole, and must be understood in the light of all available evidence. Never has there been a healthier conception of what our field should be. But, despite Bonner’s confidence, it is not a vision which has persisted. Too often today philologists hide from history, or archaeologists from Latin. But divided we cannot hope to make progress. Bonner represents the ideal of a scholar who is both capable and curious: curious enough to follow the evidence where it leads, and capable enough to grapple with it when he finds it. Let all Classicists aim no lower. (TMSN)

Classical Scholarship: A Roving Commission

Campbell Bonner

The purpose of this paper is to describe the present scope of classical studies and explain some of the modern developments in that field; and the second part of the title is an outgrowth of reflection upon what is now implied by the words “classical scholarship”. For the longer one considers the recent history of this subject and the careers of those who devote themselves to it, the clearer it becomes that few active and productive classicists of this generation or the last have confined themselves strictly within what are often supposed to be the natural limits of classical studies, that is to say the languages and literatures of Greece and Rome. Rather one will find them ranging far and wide over the ancient and into the modern world of life and thought. They go upon strange adventures of the mind, and they sometimes fall in with strange companions.

This is a modern development, yet not so modern as one might think. The old system of education, which took the classical discipline as the foundation of all intellectual endeavor, made it inevitable that the learned in all fields should be recruited from those trained in Latin and Greek; hence in the seventeenth century we see a fine classicist like Hugo Grotius becoming a master in theology and still more in political philosophy. But the phenomenal broadening of the classical field itself may be said to date from about a century ago. At that time a controversy was raging among German scholars; on the one side was the veteran conservative Gottfried Hermann with his followers, who held that the proper business of classical study was the accurate understanding of the Greek and Latin languages, the establishment of sound texts of the ancient authors, and the impeccable interpretation of them. On the other was the brilliant progressive, August Boeckh, who stoutly maintained that the field of the classics could not be confined within the limits of grammar, metrics, text criticism and exegesis; that even for the proper understanding of the ancient authors the student must have a competent knowledge of the material surroundings and the social order in which they lived; that consequently history, geography, archaeology, religion, private customs, public laws and institutions were proper and necessary parts of the classical discipline.

Today the very fact of such a controversy seems absurd; and of course there could be but one issue. The ideas of Boeckh carried the day, and the consequent broadening of the field is probably Germany’s greatest contribution to classical studies. But it is not a serious exaggeration to suggest that the average uninformed, or half-informed, impression of classical studies from the outside is about a century out of date; for it pictures the field of classics as Hermann conceived it, not as it has become through the labors of a more liberal school. There is a natural reason for this error, because it does not entirely misrepresent some phases of the situation, particularly in America. Great libraries, like great laboratories of chemistry and physics, are necessarily few; further, they are very unevenly distributed over a vast territory. Even now there are scarcely more than a dozen universities in the country that are fully equipped for what we may call the encyclopedic study of the classics. What happened when young Professor X, highly trained in Greek and Latin, found himself in a small college on a small salary, with a department library of perhaps five hundred books and five or six journals in his line of work; when he found himself unable to visit a real library except at long intervals, and realized that a journey to European museums or to Greece and Italy, would be for him the single experience of a lifetime, if it ever fell to his lot at all? He would probably read and re-read his authors. He might wish to write a book on the dramatic art of Sophocles or the idea of piety in Plato; but reflecting that he had no means of knowing how much others had done with those attractive themes, he would often turn to some subject in which there was less competition, and for which his little library sufficed, making his contribution to knowledge with a series of articles on the syntactic peculiarities of Thucydides or the vocabulary of Apollonius of Rhodes. And the uncomprehending observer not only concluded that Professor X was a trifling pedant, when he might be, and often was, a man of broad interests and fine taste, but went further and branded classical study in general as a system of word-counting and gerund-grinding.

Even when popular judgment of Greek and Latin studies is more friendly it is often mistaken. Most men who give instruction or pursue researches in the classical field are occasionally asked by some bright and breezy colleague, “Can you still find problems to work out in material that has been handled by so many students for generations?” The persistent recurrence of that question shows that we are not justified in brushing it aside impatiently, however great the temptation to do so. In fact, most of what is set forth from this point on is an attempt to answer it; and I think the answer will amply illustrate the Odysseus-like wanderings of the Hellenist.

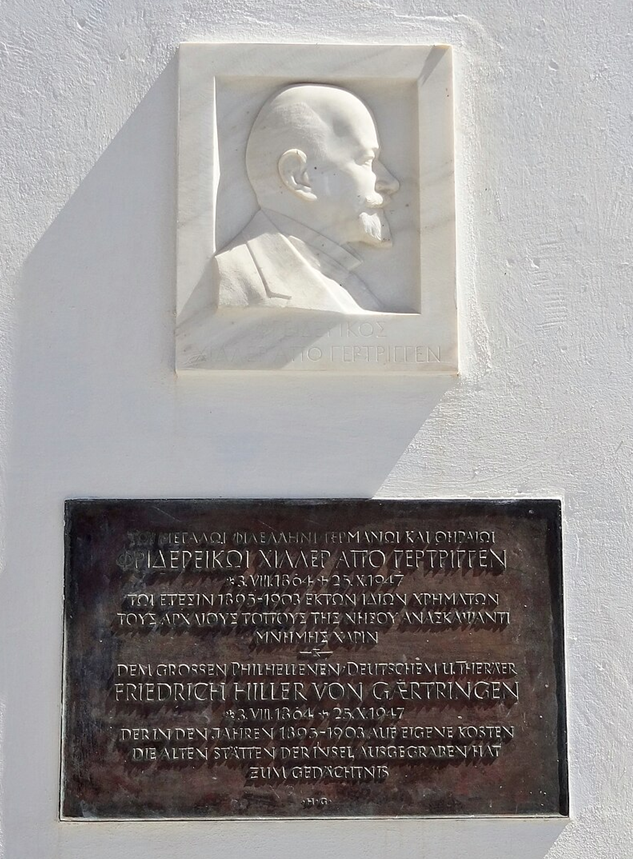

The immediate effect of Boeckh’s enlargement of the classical field showed itself in his own epoch-making work on the public economy of Athens, which brought about a new conception of Greek history, and in his insistence upon the importance of contemporary non-literary documents, that is to say the inscriptions. Thus his example directed some classical scholars into the field of history, and now all properly equipped departments or sub-departments of Greek and Roman history are guided by men who have been trained in the classical discipline and may be claimed as classical scholars. Others it led to make a specialty of inscriptions; and the field of epigraphy has been so enlarged by the constant discovery of new inscriptions that the subject has absorbed almost the entire attention of such men as [Adolf] Wilhelm in Austria, [Friedrich] Hiller von Gaertringen and [Johannes] Kirchner in Germany, and our former colleague [Benjamin Dean] Meritt in America.

In the effort to construct a clearer picture of ancient life—the life of a city or a village in war and peace, with its houses and temples, its tools, its weapons, its games, even its pots and pans—the whole field of archaeology was reopened with a fuller understanding of its problems, and was explored with tireless energy. The old authors were searched again for indications which the seekers could follow to find a lost town or sanctuary. Ancient sites were excavated, forgotten fortresses and temples were mapped and reconstructed, a wealth of new statues, new vases, new coins, new objects of all kinds were unearthed; and all of this material had to be patiently interpreted by skilled reading of the chronological data afforded by the excavation itself, by comparison of the new with the previously known, and by constant backward reference to the words of the ancients where they threw light on the new discoveries. So highly technical did this interpretation become that archeology developed into a profession in itself. Men who had been trained in the ordinary routine of classical discipline at Bonn or Munich or Oxford or Paris grew great in specialties that seemed remote from the subject of their schooling, and yet branched naturally out of it. Thus [Adolf] Furtwaengler became an authority on sculpture and gems; [Ernest] Babelon, [Barclay] Head, and [George Francis] Hill on coins; and in our own day one of the younger Oxford dons, a man who in his salad days won the Gaisford prize for a prose composition in Greek, is famous as one of the greatest authorities on the schools of painting known to us from Greek pottery [J.D. Beazley].

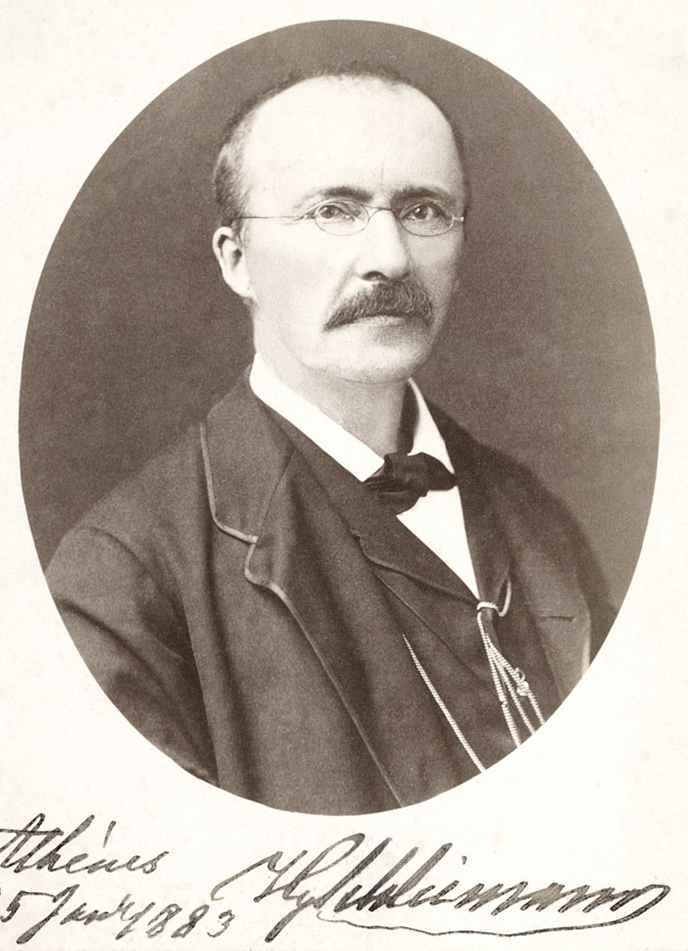

It is important to remember that these experts, no matter how far their special investigations may have led them, are classicists by training, and that they are constantly being driven back to the classical discipline by the exigencies of their technical problems. This is not to say that the only road to archeological achievement leads through the classical seminary. Weare not likely to forget what the merchant [Heinrich] Schliemann and the architect [Wilhelm] Dörpfeld accomplished for archeology, any more than we forget what two bankers, [George] Grote and [Walter] Leaf, did for Greek literature and history. Yet it is significant that when Schliemann went astray, he erred chiefly through lack of systematic training; as for Dörpfeld, he made himself a Hellenist after beginning his career otherwise. Certainly every archaeologist needs to keep himself in touch with the data of written history and literature; otherwise the most ingenious and plausible interpretation of a statue, a vase, or other artifact may be thrown out by some Hellenist who finds new evidence in a passage of Pausanias, or some obscure comment on Homer or Apollonius or Aristophanes.

But, in showing how classicists are led to wander off into archaeology, we must not forget the effect of those wanderings upon the stay-at-homes. When all who had any interest in ancient things were thrilled by the discoveries at Troy, at Mycenae, at Olympia and in Crete, no classical scholar, however much of a bookworm he might be, could shut himself up so closely among his books that the influence of these discoveries did not reach and affect him. Only a very slipshod lecturer could treat his Homer in the same way after he had learned what was found at Troy, Mycenae, and Knossos; only a purblind interpreter could read Pindar without being affected by the new pictures of Olympia and Delphi revealed by the spades of the excavators. Thus, while it is true that mastery in archaeology is too exacting an achievement to form a part of every classicist’s equipment, it is practically incumbent upon every classicist to make himself, at least in an elementary way, an archaeologist. If he does not accomplish this, he is liable to some awkward errors.

This point may be illustrated by an example. About fifteen years ago a Dutch scholar of some reputation re-read his Theocritus and published a number of learned notes on selected passages of that author. One of these passages was in Theocritus’ poem addressed to Hieron of Syracuse. The poet, not without an eye to his own pocket, is praising liberality as a virtue most worthy of princes, and by way of condemning the vice which is the contrary of that virtue he says, “to try to get the better of a man tainted with avarice is as fruitless a labor as to count the waves that the wind drives upon the seashore, or as to wash a dirty brick with clear water.” Here our Dutchman scratched his head. Why is it useless to wash a dirty brick with clear water? He probably reflected that the good housewives of Holland, true to their reputation for cleanliness, wash the bricks of their floors, their hearths, and their chimney fronts, and that even bricklayers dip a brick in water before they set it in its place. Something was surely wrong. Theocritus could not have said so stupid a thing. So he proposed to correct the text. Theocritus must have said, “wash a clear brick (that is, a brick made of glass) with dirty water,” a messy and profitless task, in all conscience. And so he neatly emended the text to read according to his refined tastes [Jacobus Johannes Hartman]. But, to say nothing of his rather surprising manufacture of bricks out of transparent glass, he overlooked a fact that every student who has traveled in Greece, and a good many observant home-keeping scholars, have had brought to their attention many times. The Greeks used for ordinary purposes not burnt, but sun-dried bricks — adobe — and he who washes a sun-dried brick has a heap of mud left for his pains. The proverb is thus founded upon a simple fact. Now this is an elementary, perhaps an absurd, example; but it will serve to point the moral that the progressive student of Greek and Latin was long ago forced out of his library and compelled to study the material aspects of ancient life, thus becoming at least a respectable amateur in archaeology.

But there are still other diverging paths which the student of Greek must explore, if not to the end, at least to some high ground whence he can get a view of the terrain. No literature which is in the main secular has ever been so completely permeated with religious ideas, with allusions to religious customs, with myths, and with popular superstitions, as the Greek. For generations commentators on the Greek poets, historians, and philosophers have had to deal with these matters, and to attempt to understand and explain them. The task has been a hard one because such subjects are usually not introduced into Greek books with a concise explanation attached, but casually, since the author could assume that his audience knew what he was talking about. Careful application of historical method cleared up many points; but a certain background of obscure, somewhat savage, custom and belief remained a puzzle until, from about 1890 on, Hellenists began to avail themselves of the methods and results of the rising science of anthropology and comparative religion. A German, [Wilhelm] Mannhardt, and two Scotchmen led the way for many other investigators; one of the Scots was the brilliant litterateur Andrew Lang, author of “The Making of Religion”, “Custom and Myth”, and many other works. The other was a retiring student, settled in a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge, and now widely known as Sir James Frazer. Frazer’s great works, “The Golden Bough” and “A Commentary on Pausanias”, whatever their faults in detail, have at least been epoch-making in one respect. They have shown us that the dark and barbarous features found here and there in Greek religion and myth are inherited from a savage past, which left its mark, half-effaced yet still legible, upon an enlightened later civilization. They also made it clear that the best aid to an understanding of that savage background is an acquaintance with the ways of thinking and living which travelers have observed still current among those peoples of the earth who are now in a backward state of social development. The practical result has been that any Hellenist who aims to do full justice to the religious and mythical data presented by his authors, and still more one who hopes to contribute anything to the understanding of such data, must wander rather widely in the field of folklore and anthropology. Such men as [Albrecht] Dieterich in Germany, Salomon Reinach in France, Sir William Ridgeway in England, are distinguished examples who have now passed from the scene. The most active and learned Greek religionist in Great Britain today, Professor H.J. Rose, has recently served as President of the Folk Lore Society. The University of Michigan may take a just pride in the numerous papers contributing to the better understanding of classical authors through a wide knowledge of folklore, which have come from the pen of its Editor of Scholarly Publications, Dr. [Eugene] McCartney.

Such things as the classical scholar may need to know about archeology, comparative religion, or anthropology come to his attention for the most part incidentally in the shape of brief allusions in the text of his authors. But there is another kind of excursion which leads him away from the mere verbal interpretation of his texts, and which is made necessary by the nature and the purpose of the works that he studies. In this respect one is inclined to think that the demands made upon the professor of Greek or Latin are somewhat more exacting than those to which his colleagues in modern languages have to respond. A professor of the English language and literature must know the place in the development of English thought which is occupied by such philosophers as Berkeley, Hume, Locke, or Green, or by such historians as Gibbon, or Napier, or Macaulay; but it is not often true that he is called upon to read and interpret large portions of their works with a class of inquiring students. Yet corresponding duties very often fall to the lot of the Hellenist and the Latinist. There are not many workers in the Greek field who may not in a short cycle of years have to discuss in detail Plato, Thucydides, and Demosthenes, as well as the poets, Homer, Pindar, Sophocles; and the Latinist must deal with Cicero, Tacitus, Lucretius, as well as with Virgil, Catullus, and Ovid.

Now it is obvious that no man can pretend to great authority as an interpreter of epic, lyric, and dramatic poetry, philosophy, history, and oratory. The native talents required are so various as seldom or never to be found in a high degree in one mind, and the mastery of the various disciplines that would be necessary is so demanding as to tax even an extraordinary brain.

Hence there comes to be a certain specialization within a field which to the layman appears to be itself a specialty. One man will give particular attention to the historians, and pretend to no special expertness in Plato and Aristotle; another will speak with authority about Greek poetry, and listen while others discuss the technique of Greek oratory and the intricacies of Athenian legal procedure. Even scholars of such versatility as [Richard] Jebb, [Basil] Gildersleeve, [Paul] Shorey, and [Ulrich von] Wilamowitz[-Moellendorf] had their specialties. But all this does not lessen the force of the contention that the average classical teacher, certainly the average university professor of classics, is expected to be moderately proficient in a variety of directions which is scarcely equalled in other fields of study. If he reads Herodotus and Thucydides he must be able to perceive the significance of geographic, economic, ethnic, and social factors in history. If he reads Plato he must be able to follow a line of orderly thought, to detect a fallacy, to grasp a general concept. If he interprets the poets, he must not be deaf to rhythm or to the delicate shades of meaning that give to poetry its subtle charm; he must appreciate artifice in words and elevation in imaginative utterance. And in all these, he must be ever conscious of the world as it existed around the great spirits of ancient times—of the proud little clan-kingdoms governed by Homer’s chieftains; of the aristocratic brilliance of Pindar’s athletic patrons; of the strange mingling of high-hearted patriotism and crude selfishness that marked the rise of the Athenian empire; of the fickle, inflammable, undependable, and yet somehow lovable democracy that is revealed to us through such different channels as the sober narrative of Thucydides, the riotous comedies of Aristophanes, and the impassioned speeches of Demosthenes.

To deal comprehendingly with different types of thought, imaginative, historical, and philosophical, is, to be sure, anaccomplishment that may be reasonably expected of a man of letters who devotes himself to any national literature; but after all, there is an added load to carry when one must interpret a fairly complex language with an amazingly rich vocabulary, and when even the prose works which one discusses are masterpieces of expression. To do full justice to Plato from a literary point of view alone is no small matter; for he is perhaps the greatest master of prose style that ever lived.

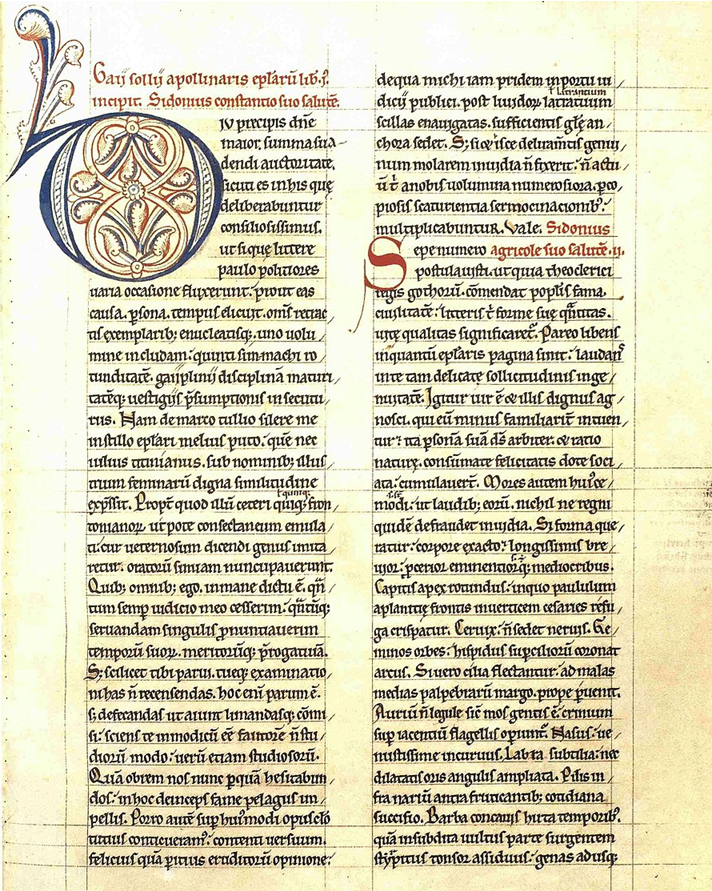

But it often happens that the classical student is led by some special circumstance to take an interest in authors other than the great masters, and in periods widely removed in time from fifth-century Athens or from Republican and Augustan Rome. The Hellenist who wishes to understand the clever satirist Lucian finds himself for the time a citizen of a world that is politically and to a large extent socially Roman; a world where Jews, Christians, and devotees of strange Oriental cults rub elbows with true Greeks. If he becomes interested in Libanius of Antioch he must read himself into the life of a huge Levantine metropolis, the meeting-place of Greece, Rome, and the Orient, the scene of some of the last battles between Christianity and fast-weakening paganism, a place where the atmosphere of life is already all but Byzantine. Not a few such adventurers into late Greek are led to plunge into the full flood of the literature, history, and art of the eastern empire; thus the even now inadequately worked Byzantine field recruits its laborers from the classical discipline, and men who began with Thucydides and Plato may end their careers as authorities on Johannes Skylitza or Michael Psellus. One may mention in passing the curious case of a British archaeologist whose early essays were concerned with Hellenic and pre-Hellenic remains, but whose travels developed in him an unusual mastery of modern Greek; so it came about that, seizing a rare opportunity, he made and published an authoritative work on “Modern Greek in Asia Minor,” with special reference to the language and the popular literature of those isolated communities of Greeks who lived among Turks and Kurds in the interior of Anatolia [Richard MacGillivray Dawkins]. The same sort of thing happens with some of our Latinists. Attracted by the view of Roman life in distant provinces that they find depicted in such late writers as Ausonius or Sidonius Apollinaris, they begin to explore the field of mediaeval Latin, and thus help to bridge the gap between the ancient and the modern world. Within the last ten years three different Latin scholars have published admirable volumes of selections from mediaeval writers of Latin, and have earned the gratitude not only of their classical colleagues but also of many students of modern literature.

There is a just complaint which is often made against classicists; namely, that they are so spellbound by the charm of the poetry and prose of the great age as to forget the importance in human history of the Christian writings and pass them by as things that make no appeal to their fastidious taste. Yet it ought to be as much a part of a Greek scholar’s business to know the New Testament, the Apostolic Fathers, the Apologists, and at least something of the great doctors of Alexandria, as to know the moral essays of Plutarch or the lectures of Dio of Prusa. Fortunately there are those who need not plead guilty to this charge. A somewhat personal illustration of this point may demonstrate further the roving propensities of the modern classical scholar. One of our group was trained in the old line of Latin studies, and enjoyed the further advantage of hearing a great authority on manuscripts, a famous palaeographer of Munich. And so, when more than twenty years ago a wealthy friend of the University brought several priceless manuscripts of the Bible to be studied and published, the work was promptly assigned to the right man, and he discharged his task with exemplary care and competence. If the governing authorities of the University at that time had understood the importance of that work as they do now, it is conceivable that those manuscripts might have been the chief treasure of our library in place of serving as a mere show-feature in a museum in Washington. However that may be, other acquisitions accrued, some in the form of vellum manuscripts, some as papyri; and naturally, the previous editor’s experience with Christian texts suggested that he should publish the new manuscripts. In this way, not to mention his increasing expertness in palaeography and papyrology, he came to have views of his own about the history of the biblical texts, particularly the New Testament documents, and the authority which should be assigned to the various branches of the tradition. With time his views have come to be shared by others, and other scholars have contributed supporting evidence. If our friend has not become a lay theologian, he has at any rate become an authority on the text of the Bible. The natural associates and colleagues of his researches are no longer editors of Livy and Tacitus, but theologians of Oxford and Cambridge, reverend professors in Berlin or Halle, learned prelates connected with the Vatican library. Thus far he has not been made a doctor of divinity, but we still have hopes; and, as the stock-peddlers say, “if and when” some bland ecclesiastical magnate puts the scarlet hood of the D.D. or S.T.D. around our colleague’s secular neck, I trust I may be there to see it [Henry A. Sanders].

A few readers, perhaps, may have missed one branch of the ramifications of classical study which used to be more talked about than it is now, but which ought not to be passed over in silence; I mean philology in the narrower sense, involving the study of words as such – historical and comparative grammar, Indo-European studies, etc. Now there can be no doubt that the grammars of Greek and Latin, studied in historical sequence from the beginnings, that is to say, from the earliest monuments of the languages to their latest developments, are of great importance for the understanding of literary works. But there seems to be a growing feeling, certainly not unjustified, that the comparative philology of the Indo-European peoples is less important from a humanistic point of view than the use made of any one of that large group of languages within times that we know and understand. As to phonetics and what is called general linguistics, the connection with the modern study of classics is even less close. The value of phonetics in teaching the pronunciation of any modern language will scarcely be disputed; the objective analysis and recording of the physical phenomena of speech has the same sort of value that any descriptive science may have; and attention to the physiology of speech may be of value in correcting defects in utterance. But it may be doubted whether, except perhaps in the case of elementary practical phonetics, any of this has any natural and proper connection with a humanistic discipline, which sets before itself the aim to understand the behavior and the thought of man at any period of his history. The habit of placing courses in linguistics of the laboratory sort in one group with languages and literature is an anomaly which will probably be corrected in the course of time.

In the matter of comparative philology, then, we have a case in which classicists wander less widely than they did in the days of [Georg] Curtius and [Karl] Brugmann. This may be a compensating contraction of interest, perhaps partly caused, and certainly more than offset, by the expansion that inevitably resulted when, beginning about 1890, the field of classical studies was immensely enlarged by a mass of new material – the yield of the rubbish-heaps of Egypt, the Greek papyri. This is not the time to describe, even in the most cursory way, the extraordinary contribution which these finds have made to our knowledge of ancient life and literature; and there is little need to enlarge upon their value here, especially since the best single book on this subject in any language has been written by one of our group of papyrologists. This is, of course, Professor [John Garrett] Winter’s “Life and Letters in the Papyri”. But it is always appropriate to speak with respect and gratitude of the great service rendered to this University by the far-seeing man who brought to it collection after collection of these documents and made it possible for the University of Michigan to become, as it is generally acknowledged to be, the center of papyrological studies in America. Twenty years ago, with the exception of Professor Sanders, who was finishing his great undertaking of editing the [Charles L.] Freer manuscripts, the members of the classical staff here were working out from time to time fairly typical problems connected with the ordinary authors of the classical curriculum – questions of interpretation, of literary relations, occasional excursions in the field of ancient history and religion and the like. But when Professor F.W. Kelsey seized a unique opportunity, and, with the aid of generous friends of the University and some subventions from the governing board, acquired lot after lot of Graeco-Egyptian papyri, he diverted the energies of several men into new channels, set before them fascinating problems which will occupy the present workers to the end of their activity and will give the next generation all they can do to complete the work which is scarcely more than begun.

The reason for introducing the subject of the papyri is that we have here a striking illustration of that wandering into unfamiliar territory which is so characteristic of classical scholarship when circumstances set before it new materials and new problems. To show just how extensive those wanderings are I must comment briefly upon the extremely miscellaneous character of these papyrus documents. First in order of number comes the great mass of non-literary material, and from this we select for separate notice the private letters. Now, not to mention the great technical difficulty of deciphering letters which are usually mutilated, often badly written, and atrociously spelled, the student must acquire enough knowledge of the topography of Egypt, the historical and economic situation at the time of its writing, and in general of the daily life of the people, to appreciate the circumstances of the writer and understand what he is writing about. Often enough the interpretation is almost a process of divination. Turning to the other main division of non-literary papyri one has immediately to subdivide again and again; for under the general caption of business or official documents we encounter a bewildering variety of texts – decrees and proclamations of high officials, petitions and complaints addressed to magistrates, reports of court proceedings and decisions upon law cases, records of contracts, agreements, leases, sales, receipts for taxes, receipts for payment of private debts, and many other sorts of papers. Such material naturally falls to the lot of the ancient historian and the classical student who is interested in the political and economic surroundings of ancient life. But consider how such workers must extend and adapt their equipment of knowledge as they proceed with their task. It is no light undertaking for a man who knows the daily life of Athens in the time of Aristophanes to assume at short notice the responsibility of editing and commenting on a group of private letters written in Egypt in the third century of our era, some six hundred years after the glories of Periclean Athens were past. Similarly a student of history who is familiar with the constitutional and administrative development of Rome has much to learn before he can write with knowledge and authority about the intricate organization under which Egypt was governed at different periods from the Ptolemies to the coming of the Arabs.

Literary papyri lead the student just as far, though in different ways. If we are considering a fragment which we can identify as part of a known work by a known author, it might seem a very simple matter to prepare it for publication, especially since we can use a printed text to help us decipher an illegible passage in the papyrus. But there are many surprises. Our printed texts represent the judgment of modern editors upon the relative value of the mediaeval manuscripts through which we know most of the ancient authors. But the papyri by no means agree regularly with what we have supposed to be the best texts. Hence the reader must be ever watchful, in order to be sure what he has before him; and in order to evaluate a papyrus text he must master at least the main points in the textual history of the medieval manuscripts, and there every author presents a separate problem. I may add that it is not always a simple matter to identify even a known text. Our dictionaries and indexes help us to follow up promising catch-words, but we do not always find an outstanding characteristic word by which to judge a text. If one should tear out a page of an edition of the Spectator and then tear from that page a small irregular slip containing a few sentences, with the first half of every line gone, there might be enough left to enable an expert in English literature to say, “That has a flavor of eighteenth century style”; but who could say offhand that it was written by Addison, and not, for example, by Goldsmith?

The case of previously unknown texts is infinitely more difficult. Few literary fragments present us with the name of their author. We can say, “This is a fragment of lyric, or dramatic, or epic poetry, a bit of an essay, an oration, or a historical narrative.” But if after careful searching it is not found to belong to any extant work, then the papyrologist can only draw upon his knowledge of literary history and his feeling for the styles of individuals or periods and say, “This bit of dramatic poetry may belong to a play of Menander or one of his less known contemporaries; that is some verses from an Alexandrian epic; that is from a geographical work, probably of the Hellenistic age,” and so on. The result is that books of literary papyri offer us a good many specimens of still unidentified works. Most exacting of all are texts belonging to types of literature that form no part of the ordinary reading of the average classicist, such as medicine, mathematics, astronomy, magic, and astrology; for in dealing with such material the classical scholar has to learn the technical vocabulary of a scientific or pseudo-scientific subject, and has to know something of the dominating ideas or theories pertaining to very unfamiliar fields.

One of our researchers began his career with a solid grounding in Greek philosophy, acquired under a master in that subject; he also happened to have a natural aptitude for mathematics and a certain interest in that field. Some years ago circumstances led him to study and translate a Greek work on numbers – one could scarcely call it arithmetic in our sense of the word. Later, when our papyri were sorted and classified, it was found that they comprised portions of unknown works on astrology and astronomy, and some problems or exercises in arithmetic. Naturally these texts were promptly passed over to our classical-mathematical colleague in the hope that he could ride those two somewhat ill-paired horses in one act, and the rest of the group heaved a mighty sigh of relief. As a result, he has developed a sort of specialty of his own and has revealed by his studies some new aspects of ancient arithmetic and astrology [Frank Egleston Robbins]. He can get no help and very little comprehension from his classical colleagues here whose versatility does not extend to mathematics; but we have an astronomer who understands what he is about, and, as for other appreciation, he receives it in plenty from distinguished specialists abroad.

Now it is obvious that no one man can follow all the paths that lead away from the main trunk-road of classical studies. But it should be clear from the examples cited that, whether he devotes himself to the old time-honored masters or pursues the lines of investigation opened up by recent discoveries, the classical scholar will rarely be a mere grammarian or a mere translator and commentator of old texts. Even if he cleaves closely to authors of the great period, his duty to the students whom he guides will lead him to interpret the classroom texts with a view to their historical and philosophical significance and to their literary value. If his interests tend strongly to history, he will pursue certain auxiliary disciplines, and will extend his view beyond classical times to the beginning of the middle ages or beyond. If he is by natural taste something of a religionist, he will acquaint himself with the ways of thought that are characteristic of men in a simple stage of civilization, and will learn something of the religions of peoples other than the Greek and Roman.

If archaeology attracts him, he must not be wholly ignorant of the general history of art, nor helpless in the field of art criticism. It may easily happen that his studies will lead him gradually to the mastery of highly specialized techniques, such as the knowledge of the tools used in sculpture, the processes of metal-casting, the methods and the styles of architecture, the clays and glazes employed in the potter’s craft, the dies and the mint marks used in striking coins. If he studies the Old or the New Testament in Greek, he may find it necessary to become a belated student of Hebrew or Coptic, and in one way or another he is rather likely to cross the line and enter the field of theology. And, as it has been shown, if he assumes the task of editing and interpreting new texts, whether they be new inscriptions or new papyri, he must often follow out a quite unfamiliar line of research, leading into some remote and scarcely explored province of ancient life and thought.

If one could outline on a blackboard or throw on the screen a sort of family tree showing the ramifications of classical studies, it would probably be just as complicated, but also just as useful, and more intelligible, than one of those charts illustrating the organization and the finances of the University of Michigan – one of those charts that our administrative officers pull out of a drawer and solemnly spread out on the desk when they are going to explain just why something imperatively necessary cannot possibly be done. But on the whole, rather than use a chart, let a poet speak:

Greek puts already on either side

Such a branch-work forth as soon extends

To a vista opening far and wide,

And I pass out where it ends. [from Robert Browning’s “By the Fire-side” (1855)]

It is high time that not only a university public, but the general public also, should take a truer and a more modern view of the aims and scope of classical studies. One still hears people speak of Hellenists and Latinists as if they were monkish scholars working in a narrow cell, when in reality the range of their researches and even the range of their routine teaching is astonishingly broad; for their aim is the complete understanding of the thought and the actions of men in ancient Greece and Rome, and the vivid and vital reconstruction of the world in which they lived. Nothing human is alien to them, and the field in which they labor is rightly called humanistic. Recognizing that ancient languages seem an obstacle to many people, they have labored hard and are still laboring, to put all the substance of ancient thought before modern men in modern translations. But no honest classicist can say that in providing a translation he is offering the rich flavor, the untransmutable charm of ancient poetry or artistic prose. The most serious complaint that the classicist has against modern educational practice is not that it no longer requires all students in upper schools and colleges to learn Greek and Latin – nobody wants the task of inducting every boy and girl into the tremendously expanded field of modern classical study – but that through hostility or through uncomprehending indifference it discourages those who would most enjoy ancient literature, the lover of poetry, the savorer of style, the enthusiastic explorer of unfamiliar scenes, the keen appreciator of new and strange personalities, from overleaping the comparatively trivial hurdle of another language. And yet a foreign language is the last barrier that an educated person can afford to leave standing between himself and a noble mind of another race and another age.

People sometimes say: “Your discoveries, your conclusions, your new-found materials, the whole substance and method of your work, are small in the eyes of the modern world.” Perhaps, unless we are willing to ponder upon a phrase written not by a philosopher or a scholar but by a singularly hard-headed and practical man who happened to be a novelist also, Anthony Trollope, who somewhere speaks of “the permanent utility of all truth and the permanent hurtfulness of all falsehood” [from The Claverings (1867), with “injury” for “hurtfulness”]. But those who despise little things would do well to consider the mighty structures which modern sciences, physics, biology, geology, chemistry, have erected upon the basis of minute and seemingly trivial observations. Again we hear it said: “We grant you the beauty of ancient poetry, the profound interest of ancient life and thought. But that is all a part of a remote past – why spend time and effort upon it when modern life, modern art, and modern poetry are teeming with interest around us?” Such an attitude is natural and characteristic in the young, and may be viewed leniently in them; in older people it is not so easy to excuse. Those who take that position virtually deny that man of today can profit by past experience, a thing which even animals are observed to do with a fair measure of success. However, this battle is by no means the exclusive concern of classical students; and now that Greek and Latin have been thrust from their position of leadership, the baton of command may as well be offered to the departments of English and History, which will find it to their advantage not to underrate the enemy. For those who decry the interest and the worth of things ancient are capable – and have shown it – of extending their condemnation to the more recent past, and of using Shakespeare, Pepys, Johnson, and Macaulay, no less than the clay of “imperious Caesar”, to stop a hole and keep the wind away. Let the consuls see to it that no harm befall the state.

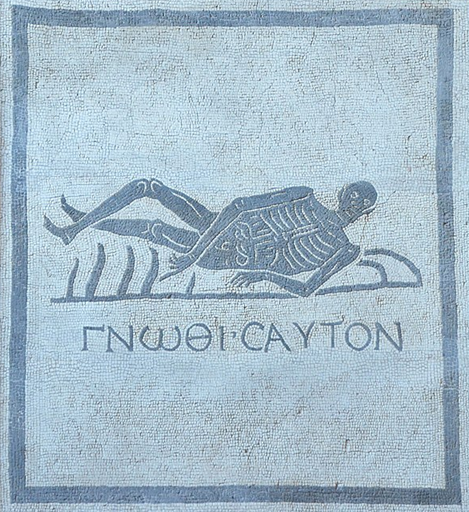

It is said that the ancient maxim, “Know Thyself,” was honored by the Greeks with a place in the temple of Apollo of Delphi, where it was inscribed on a tablet at the entrance. Perhaps even a rapid survey of the scope and the aims of classical study should not conclude without some consideration of the effect which this widely branching subject, or group of subjects, exercises upon those who apply themselves to it. Such an estimate might seem to come more appropriately from without rather than from within the profession; but after all, any craftsman is most faithfully judged by his fellows, and years and lengthening experience tend to detach one from merely partisan judgments. First then, by way of clearing the ground for more definite observations, allow me to make the general remark, a platitude if you will, that the most enthusiastic champion of the classics will scarcely find in their study a sure cure for everyday defects of the mind, vices of temper, or blemishes of character. We may find among those who have made a profession of classical scholarship the lazy, the self-indulgent, the self-seeking, the mean-spirited, the prejudiced, the pretentious, the boaster, as they are to be found in every other profession, even the most sacred. Which only means that no discipline offers us a perfect solvent for the dross inherent in human nature.

Yet even as life can sometimes provide what schooling does not, so a system of study which encourages the student to meditate long upon the ways of man, even ancient man, may help him to avoid some errors of thought and action. Even a slight acquaintance with Plato may very helpfully remind one, at some critical time, of the difference between appearance and reality, between mere opinion and truth itself. No man who cherishes his acquaintance with Socrates is likely to forget the duty of self-examination or to be greatly overawed by finding himself in a minority; he will not be greatly impressed when told that this course of action ought to be followed, or that plan ought to be adopted, because “everybody” favors it and it has already been taken up by a majority of the business firms, the law offices, or the university faculties of a great country. There is a saying attributed to Socrates in the Phaedo, the implications of which are sometimes overlooked: “False words are not only evil in themselves but they also infect the soul with evil.” Now the context clearly shows that the application intended is simply this: that slovenly, inaccurate speech not only proceeds from, but may actually cause, slovenly thinking. It is, surely, no extravagant claim that most classically trained men have taken that lesson to heart; certainly it is true that, being accustomed to languages which adapted themselves to express both philosophic and scientific ideas with surprisingly little departure from ordinary literary style, the classicist profoundly distrusts jargon, particularly the slipshod, uncouth, osteopathic wrenchings of the English language which pervade the vocabulary of the third-rate group, the C-minus grade, of psychologists, educationists, and sociologists.

All this may be characterized as mere conservatism. Classicists are conservative in the good Latin sense of the word; they favor keeping what is proved good, even if it must be in a transformed state. And conversely, they have a wholesome dislike for the idea of buying a pig in a poke, and for trying nostrums and cure-alls, whether political, economic, social, or educational. Classicists have been called conventional. Again yes, but with certain qualifications. The man who knows his history or his anthropology will not reject conventions hastily, because he knows what human society owes to them, and how they have helped to raise humanity up from barbarism. If he still follows some that have degenerated from substance to mere form, he will wear these unsubstantial fetters with an easy casualness, and refuse to be hampered by them. And finally – for the subject is endless – classical scholarship in all its wanderings shares with history and the sciences an unshaken faith in the value of the pursuit of knowledge, both for the services which it can obviously render to man, and as an end which will somehow find its place in the scheme of things, even though it escapes our present comprehension. In that pursuit the classical scholar is content to spend his life without repining and with steadfast hope.