Solveig Lucia Gold & Joshua T. Katz

In a bid to increase enrollment, especially of students of color, the Princeton Department of Classics in the spring of 2021 made the now infamous decision to eliminate its language requirement for undergraduate majors so that students could graduate with a degree in Classics without ever taking a single course in Latin or Ancient Greek.* The decision enraged many alumni and outside commentators, who marveled at the department’s soft bigotry.[1] As the linguist John McWhorter put it, “The Princeton Classics department’s new position is tantamount to saying that Latin and Greek are too hard to require Black students to learn.”[2] The decision also left people scratching their heads: what does it mean to do Classics without the languages?

It’s a good question.[3] While Classics is an interdisciplinary subject, knowledge of Greek and/or Latin has traditionally been the one thing all Classicists share, whether their focus is papyrology or archaeology. And more specifically, all Classicists have traditionally been trained in the subfield that binds the whole field together: philology.

What is Classical philology?[4] The best point of reference for an American audience may be this: it looks a lot like textualist and originalist approaches to constitutional interpretation. Classical philology, as we were trained to do it, is the attempt to understand a text as it was produced in its historical context, with as few anachronistic preconceptions as possible. The Classical philologist unpacks each word or phrase by comparing it with other uses of the word or phrase in a given author’s corpus – and in the broader corpus of texts to which that author would have been exposed.

Philology was long the core of Classics because it in some sense provided a unifying purpose for the different subfields: literature, philosophy, history, linguistics, papyrology, epigraphy, numismatics, textual criticism, art history, and archaeology – all are important tools for the philologist who works to uncover a text’s context, and philology is an important tool for these subfields in turn. So central was philology to the discipline that, from 1869 until 2014, the Society for Classical Studies, the main learned society of Classicists in North America, was called the American Philological Association.

But as both this name change and Princeton’s elimination of its language requirement reflect, philology is no longer the core of Classics.[5] It has been replaced by a form of activist teaching and research – recently bolstered by a $1-million grant from the Mellon Foundation to Sasha-Mae Eccleston and Dan-el Padilla Peralta, professors of Classics at Brown and Princeton, respectively, for their initiative “Racing the Classics”[6] – that prizes such presentist concerns as identity (race, gender, sexual orientation, class, indigeneity, and (dis)ability), politics, and the environment.

This new approach aims, at turns, to use Classics to solve contemporary problems,[7] to project contemporary problems onto the analysis of Classical material, and to look at how the reception of Classical material has caused or perpetuated many of these problems in the first place.

At the heart of this approach is a methodology – best summarized by Mathura Umachandran and Marchella Ward in the opening chapter of their co-edited 2024 volume Critical Ancient World Studies: The Case for Forgetting Classics[8] – that

critiques the field’s Eurocentrism and refuses to inherit silently a field crafted so as to constitute a mythical pre-history for an imagined ‘West’… [I]t rejects the assumption of an axiomatic relationship between so-called classics and cultural value… [I]t denies positivist accounts of history, and all modes of investigation that aim at establishing a perspective that is neutral or transparent, and commits instead to showcasing the contingency of history and historiography in a way that is alert to the injustices and epistemologies of power that have shaped the way that certain kinds of knowledge have been constructed as “objective” within the discipline known as classics… [I]t requires of those who participate in it a commitment to decolonising the gaze of and at antiquity.[9]

In short, there’s a whole lot of discussion about Classics, but very little, well, Classics.[10]

And when there is analysis of Classical texts, it increasingly looks like this: “Through a combination of Audre Lorde’s Black queer lens and Paul Preciado’s trans scholarship on the dildo, I further argue that by imagining Simulus as Black, queer, and/or trans, the power imbalance between Simulus and Scybale is greatly reduced.”[11] This sentence from a scholarly article, chosen more or less at random (and written, incidentally, by a white cisgendered woman), comes from the Spring 2024 issue – a special one titled “Race and Racism: Beyond the Spectacular” – of TAPA, the journal formerly known as the Transactions of the American Philological Association. Despite its peculiarities, the article in question exhibits a far-greater command of traditional philology than much of what makes it into TAPA these days[12] – or, for that matter, into the American Journal of Philology, which has published two special issues in recent years titled “Diversifying Classical Philology,”[13] with articles that, in the words of guest editor Emily Greenwood, “exemplify a practice of intramural counter-philology—of turning the tools of philological criticism onto the discipline to examine its sources of cultural knowledge, ways of knowing, and its lacunae.”[14]

Philology, you see, has become a dirty word – for three primary reasons, best articulated in the writings of Eccleston, Padilla Peralta, Greenwood, and Patrice Rankine.[15] Although their arguments are often jargon-heavy and difficult to parse, we have worked to reconstruct the charges against philology below. It is high time for someone to challenge what has quickly become gospel in our field – and, for that matter, in society at large, where both objectivity and “worship of the written word” have been branded “white supremacy.”[16] It is high time, in short, for an apology for philology.

1. Philology’s Racist Past

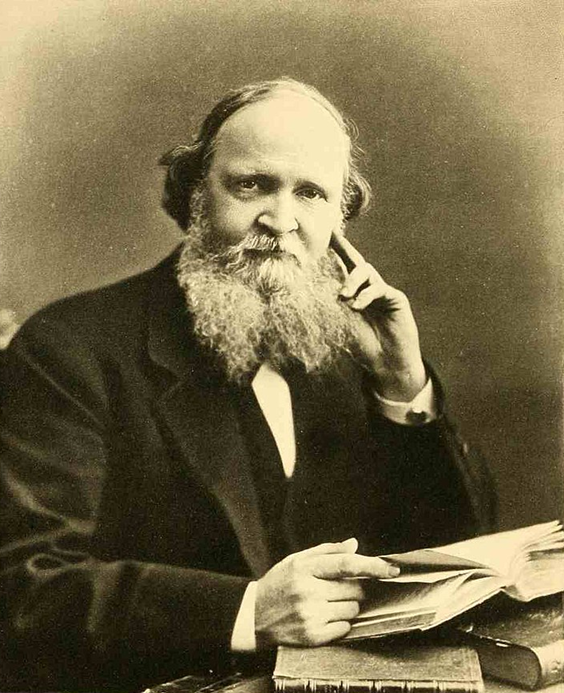

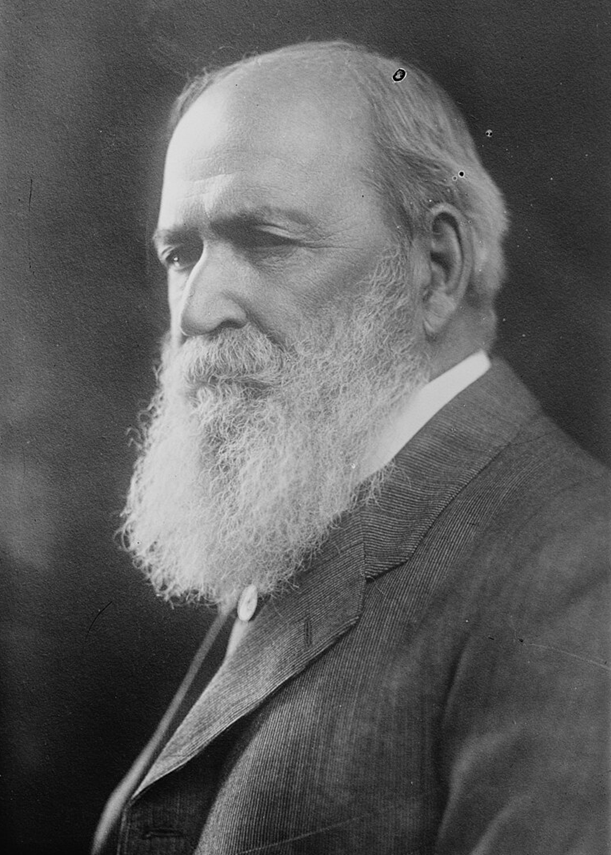

So what are the three charges against philology? First, that philology was historically associated with slaveholders, imperialism, and race science.[17] In particular, until recently, Classicists revered the legacy of Basil L. Gildersleeve, the founder of the American Journal of Philology,[18] who was, however, a slaveholder and fought for the Confederacy.[19]

This charge is undeniable but not all that remarkable: every longstanding field of inquiry has been shaped by people with reprehensible views, many of them involved in reprehensible practices. Those views and practices do not necessarily implicate the inquiry: Schrödinger was a pedophile, but that has no bearing on his cat. Moreover, even if Classical philology had been explicitly engineered to be a means of supporting, say, slavery (it was not), the philological method would not necessarily be compromised.[20]

To prove that Classical philology cannot be disentangled from its slaveholding past, the accusers would have to demonstrate that the method itself is compromised. And they do attempt to do this – their second charge against philology.

2. Philology’s Intrinsic Whiteness

To quote Rankine from 2019, “philology professes to retreat from all contemporary inquiry, fixing its gaze on the past.”[21] But this “is and always has been a pretense, and a pernicious lie”[22] because, as Rankine puts it in the introduction to the Spring 2024 issue of TAPA, “the race-neutral, colorblind position was simply an unconscious strategy of concealment.”[23] That is, “Repressing the Oedipal secret of your identity (which is hidden in plain sight), it might never occur to you that your ability to read and write about Euripides… unimpeded by anything but the text, manuscripts, and your outstanding philological training owes to your racial identity, your whiteness.”[24]

In other words, white scholars are so accustomed to a culture of whiteness that we do not realize how whiteness colors everything we do, including how we read ancient texts. We may think we have developed an impartial, near-scientific method of textual interpretation, but really philology is a means of blindly projecting our contemporary white biases onto the past under the guise of objectivity.

We – by which we mean Solveig and Joshua, not all “white” scholars – find this charge bizarre because philology, or at least good philology, forces us to acknowledge precisely those contemporary biases that Rankine seems to believe it actively conceals. A good philologist knows that when she reads just about any word in Greek or Latin, she will project onto the word a whole host of meanings and references that have accumulated around the word (and corresponding words in other languages) in the past two thousand years. Her task – the task of a philologist – is to strip away those meanings and get to the meaning of the word as it was originally written. She does this by reading widely and deeply on the use of the word in the ancient world. She never takes for granted that she knows what a word in a text means simply because she can translate it into her native tongue.

An example in English. We’ve called this article “An Apology for Philology”. A naive reader would almost certainly assume that the title is introducing a regretful acknowledgment of philology’s failures. However, a careful reader – a good philologist – would consider 1) that the article does not seem to harp on philology’s failures, 2) that the article is about Classics, 3) that Solveig’s main area of expertise is Plato, and 4) that catchy titles often play with non-obvious meanings of words. And in view of all this, the good philologist would, and should, conclude that “apology” here refers not to the usual meaning in 21st-century English but rather to the earlier (now secondary) meaning that comes from Greek ἀπολογία (apologiā, “defense”), as in Plato’s Apology.

What the naysayers are criticizing is not philology; it is bad philology. Now, it would seem that their next move is to allege that there is no such thing as good philology – that it is simply impossible to strip away all our contemporary biases when evaluating an ancient source, impossible to “un-race” ourselves.[25] As Greenwood writes, “our way of life is not embodied in ancient Greek or Latin, instead we embody these languages and impart our values to them, no matter how scrupulous or objective we think we are being.”[26] To this we say: sure, it probably is impossible to strip away all our biases. But that does not mean we should throw in the towel, give up trying to understand the ancients on their own terms, and resign ourselves to identity-driven studies. Impartiality, however unattainable, remains a worthy goal.

Besides, we have yet to see evidence that the impossibility of fully “un-racing” ourselves actually does have a significant impact on philological scholarship. Where are all these white supremacist (mis)readings of (e.g.) Euripides? The naysayers never give an example. Or rather, Rankine gives one example in each of his articles under discussion – neither from philological scholarship.

First: “At the heart of classical philology’s claim to impartiality and critical distance, the notion that study of the languages per se is the pathway to truth and understanding, is race.”[27] In a footnote to this sentence, Rankine states that “[a]ny number of examples could support this point” and then cites five pages from E.R. Dodds’s seminal 1951 book The Greeks and the Irrational that, Rankine claims, are “steeped in the paradigms of anthropology (at the time) and the field’s articulation of African primitivism.”[28] “His method,” Rankine concludes tersely, “is philological.”

Dodds was indeed a major philologist, but this book was an explicit effort to make use “in several places of recent anthropological and psychological observations and theories,”[29] and the pages Rankine cites are all examples of this anthropological approach, not philology. For instance, Dodds mentions an uptick in superstition among the Tanala tribes in Madagascar as a possible point of comparison for a similar phenomenon in Archaic Greece.[30]There is no careful analysis of text. Moreover, Dodds was well aware that his use of anthropology was historically contingent: “in these relatively new studies the accepted truths of to-day are apt to become the discarded errors of to-morrow.”[31] So much for a supposed “claim to impartiality”.

Then there is Rankine’s other article, in which his example comes from 19th-century language instruction. He wildly misrepresents his source, in a staggering act of intellectual sloppiness or dishonesty, and it is worth quoting a large portion of the relevant paragraph:

Once it is clear that motives… are impure, the uneasy connection between race and the Classics is exposed as iron-clad, rather than incidental… An example: Denise McCoskey has studied Latin language instruction and the subject of slavery in 19th-century grammar books. In an unpublished paper, she works to “determine the kinds of ‘classical values’ students were absorbing not by reading, say, Tacitus or Vergil, but by learning noun declensions and completing practice exercises.” This may not seem like an ideologically loaded exercise; and yet the seemingly innocuous use of the English “servant” for servus in the American context belies real efforts at erasure, the rubbing out of the enslavement of Africans that began in Virginia in 1619. This enslavement and its erasure, by representing the abject status of the “slave” with the far less degraded status of the “servant,” impacts the subsequent status of blacks in America as second-class citizens… Ostensibly innocent, the rendering of servus as “servant” obfuscates the relationship between the Roman world that an American student enters through the Latin grammar book and her own contemporary prism… Equally pernicious, the student does not even learn about the cruelty that was Roman slavery, cruelty now excused by notions of historical relativism and revisionism because “slaves” or “servants,” after all, must deserve and desire their status.[32]

Rankine’s argument, as we understand it, is that 19th-century grammar books translated servus “slave,” as “servant,” which allowed students to read about the ancient world without having to confront the reality of slavery in their own time.[33] He also seems to suggest that this obfuscation continues in language instruction to this day. And, as the article goes on, Rankine returns to the (mis)translation of servus as evidence of our inability ever to view the past objectively: “If a move as seemingly innocent as ‘servant’ for servus belies the neutrality that it seems to present, imagine how cloudy is the view of modern concerns that quicken the study of the past in the first place. Our Oedipal blindness is total.”[34] The trouble is that Rankine’s source for the mistranslation, the then unpublished paper by Denise McCoskey, “belies” his argument.

McCoskey’s (now published) paper[35] identifies a number of problems in contemporary language instruction: for instance, the Cambridge Latin Course’s use of the sentence servī erant laetī, “the slaves were happy.”[36] There is no mention, however, of anyone nowadays teaching servus as “servant”. More important, though, is that there is scarcely any mention of servus being translated as “servant” in the 19th century either. McCoskey gives only two examples, in passing, from one 1839 schoolbook – a book that alternately translates servus as “servant” and “slave”. And this book, published in abolitionist Boston, she actually commends for “its covert attempts to speak against the institution of slavery.”[37]

Indeed, Rankine entirely misrepresents the thrust of McCoskey’s paper, which is that 19th-century Latin schoolbooks were in fact better at discussing the brutal reality of slavery than our books are today: “generally more intense and more anxiety-ridden,” the older works “tend to treat slaves as autonomous subjects” and “present a more frank portrayal of the institutional forces that perpetuate slavery, such as violence and law.”[38] In other words, the alleged failure of contemporary language instructors to teach about the cruelties of slavery is not historically entrenched, and “the uneasy connection between race and the Classics” is not “iron-clad” – or at least, Rankine hasn’t proved that it is.

3. Philology’s Weaponization

Finally, the third charge. Philology, which “pretends to be a neutral and disinvested test of intelligence”,[39] is associated with ideas like merit, rigor, and excellence. It has thus, the naysayers allege, been weaponized to dismiss other approaches to Classics, including non-philological work of the kind highlighted above.[40] To quote Eccleston and Padilla Peralta, “the presumptive rigor of philology functioned as much more than a mode or metonym of exclusionary elitism throughout the field. Institutional gatekeepers levied it as a slur that effectively sidelined Black- or Brown-centered methodologies—especially in reception studies—as mesearch.”[41]

There is good philology; there is bad philology. There is good reception work; there is bad reception work. We are apologists for philology, but we do not believe that philology is the only worthy way to do Classics. We would, however, like to see excellence across the board. This means maintaining high standards in both language instruction and scholarship. Students should be competent in Greek and Latin, and scholars at all levels should be expected to marshal (correctly cited) evidence creatively to make valid – and ideally also sound – arguments in a comprehensible way. This comprehensibility matters precisely because it is what makes the scholarship accessible to non-specialists – that is to say, what makes it not exclusionary or elitist. Still, no, not everyone can do it. Excellence necessarily excludes.

But it does not necessarily exclude any one group of people. It is not white supremacy in disguise. According to Rankine, we “have to give the lie to seemingly neutral notions of excellence, just as we unveil the true motives of ‘servant’ for servus.”[42] But now we have given the lie to his unveiling, and we see it for what it is: the weaponization of bad philology.

Solveig Lucia Gold is Senior Fellow in Education and Society at the American Council of Trustees and Alumni. She holds a PhD in Classics from the University of Cambridge and has published in venues such as Classical Quarterly, First Things, The Free Press, the New Criterion, and the Wall Street Journal.

Joshua T. Katz is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and was formerly Cotsen Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Classics at Princeton University.

* This article was first published as a chapter in Lawrence M. Krauss (ed.), The War on Science: Thirty-Nine Renowned Scientists and Scholars Speak Out About Current Threats to Free Speech, Open Inquiry, and the Scientific Process (Post Hill Press, New York, 2025) 192–200. Reproduced with permission.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Both of us have written about what Princeton did: Solveig Lucia Gold, “Princeton and the Erosion of Expertise,” First Things, June 10, 2021, available here; Solveig Lucia Gold, “Rebuilding the Classics,” City Journal, December 16, 2022, available here; and Joshua T. Katz, “Classics: Inside Out and Upside Down,” Academic Questions 36.1 (Spring 2023) 89–104, at 95–7, available here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | John McWhorter, “The Problem with Dropping Standards in the Name of Racial Equity,” The Atlantic, June 7, 2021, available here. |

| ⇧3 | For a nuanced answer by an outstanding Classical philologist, see Wolfgang de Melo’s two-part article “Classics in Translation? A Personal Angle,” Antigone, March 2023, available here and here. While de Melo concludes that “not every student of the ancient world needs to learn Latin and Greek,” he drives home the point that “we should not get rid of language training and translation practice just because certain strands of activists are pushing for this to happen.” |

| ⇧4 | For a historical account of philology generally, see James Turner, Philology: The Forgotten Origin of the Modern Humanities (Princeton UP, NJ, 2014). Turner notes that “in the nineteenth century [it] covered three distinct modes of research: (1) textual philology (including classical and biblical studies, ‘oriental’ literatures such as those in Sanskrit and Arabic, and medieval and modern European writings); (2) theories of the origin and nature of language; and (3) comparative study of the structures and historical evolution of languages and of language families” and goes on to state that “[a]ll philologists believed history to be the key to unlocking the different mysteries they sought to solve” and, “[m]oreover, all breeds of philologist understood historical research as comparative in nature” (x; italics in original). |

| ⇧5 | Philology has also failed as a discipline in its own right: see John Guillory, Professing Criticism: Essays on the Organization of Literary Study (Univ. of Chicago Press, IL, 2022), esp. ch. 6 (“Two Failed Disciplines: Belles Lettres and Philology,” 168–98). The cover of Guillory’s book illustrates the point. |

| ⇧6 | See, e.g., this announcement (December 23, 2023). Eccleston and Padilla Peralta laid out their agenda in “Racing the Classics: Ethos and Praxis,” American Journal of Philology 143.2 (Summer 2022) 199–218, available here. |

| ⇧7 | See Alice König, “Teaching Classics as an Applied Subject,” Journal of Classics Teaching 25 (Spring 2024) 8–16, available here, for an account of “Applied Classics” (defined as “the purposeful application of carefully-chosen aspects of antiquity as a useful, focused intervention in a contemporary challenge,” 9) and a description of a course she has led at St Andrews. Likewise, at Princeton, Brooke Holmes and Dan-el Padilla Peralta, together with the two co-founders of the Activist Graduate School, turned a graduate seminar into a “lab for students and professors alike to envision the inter- and extra-disciplinary communities that might emerge from a rupture within a classical tradition whose founding myth is one of privileged continuity with the past.” |

| ⇧8 | Mathura Umachandran & Marchella Ward (edd.), Critical Ancient World Studies: The Case for Forgetting Classics (Routledge, London, 2024), available open access here. Two biting reviews have so far appeared: Jaspreet Singh Boparai, “When Classicists Attack Classics,” The Critic, April 5, 2024, available here, and Mateusz Stróżyński, “‘Critical Ancient World Studies,’” Classical Review 74.2 (October 2024) 651–4, available here and here. |

| ⇧9 | Umachandran & Ward, “Towards a Manifesto for Critical Ancient World Studies,” in Umachandran & Ward (as n.8) 3–34, at 3. In his contribution to the volume, “In the Jaws of CAWS: A Response” (255–63), Dan-el Padilla Peralta states that decolonizing Classics means land redistribution: “By decolonisation, I mean the labour of redistributing the material conditions of knowledge production, beginning with the land expropriated violently through settler-colonialism” (259). |

| ⇧10 | This is, of course, true of the present article as well. |

| ⇧11 | Francesca Bellei, “The Nose at the Crossroads: An Intersectional Reading of the Pseudo-Vergilian Moretum,” TAPA 154.1 (Spring 2024) 213–50, at 213, available here. |

| ⇧12 | Or that is accepted for presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Classical Studies: see, e.g., Gold, “Rebuilding the Classics” (as n.1). |

| ⇧13 | American Journal of Philology 143.2 (Summer 2022), available here, and 143.4 (Winter 2022), available here. |

| ⇧14 | Emily Greenwood, “Introduction: Classical Philology, Otherhow,” American Journal of Philology 143.2 (Summer 2022) 187–97, at 190, available here. It may or may not be worth comparing “counter-philology” with the idea of “junk philology” or “punk philology” espoused by Dan-el Padilla Peralta, “Junk Philology: An Anti-Commentary,” Diaphanes, August 13, 2021, available here. |

| ⇧15 | Rankine and Eccleston are the guest editors of the issue of TAPA mentioned just above. |

| ⇧16 | See here. For the importance of this list in American culture, see Nellie Bowles, Morning after the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History (Thesis, New York, 2024) 54–7. |

| ⇧17 | See, e.g., Patrice Rankine, “The Classics, Race, and Community-Engaged or Public Scholarship,” American Journal of Philology 140.2 (Summer 2019) 345–59, at 347–9, available here, and Eccleston & Padilla Peralta (as n.6) 210, with references in their n.28. |

| ⇧18 | When Joshua gave a lecture at the University of Virginia in November 2019, he was escorted ceremoniously to Gildersleeve’s grave! |

| ⇧19 | Gildersleeve “viewed what he and other Southerners called the ‘War Between the States’ through the lens of the Peloponnesian War.” Thus Margaret Malamud, African Americans and the Classics: Antiquity, Abolition and Activism (I.B. Tauris, London, 2016) 140, cited (inaccurately) by Rankine (as n.17) 348. |

| ⇧20 | As it happens, this very point is made by one of the contributors to Critical Ancient World Studies in his account of the unsavory history of the subdiscipline of linguistics known as comparative philology (Turner’s third mode of research [see n.4] and Joshua’s main academic interest): Krishnan J. Ram-Prasad, “Comparative Philology and Critical Ancient World Studies,” in Umachandran & Ward (as n.8) 91–106. “From its very foundation as a discipline, I[ndo-]E[uropean] comparative philology was designed to be contingent on, and supportive of, colonialism” (94), Ram-Prasad claims with some justification. The founding figure Sir William Jones, who in 1786 hypothesized the existence of “some common source” for Sanskrit and various European languages, learned Sanskrit when he lived (and died) in India as a colonizer. Still, “[t]hat he was in a position to make such an observation because of colonialism does not mean that the observation itself was merely a colonial fantasy. Nor indeed does our contemporary acceptance of the Indo-European hypothesis make us neocolonialists” (95). |

| ⇧21, ⇧34, ⇧39, ⇧42 | Rankine (as n.17) 352. |

| ⇧22 | Ibid. 353. |

| ⇧23 | Patrice Rankine, “Racializing Antiquity, Post-Diversity,” TAPA 154.1 (Spring 2024) 1–15, at 6, available here. |

| ⇧24 | Ibid. 9. |

| ⇧25 | Compare Eccleston & Padilla Peralta (as n.6) 201. |

| ⇧26 | Greenwood (as n.14) 194. |

| ⇧27 | Rankine (as n.23) 10. |

| ⇧28 | Ibid. 10 n.33. The pages he cites are from E.R. Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational (Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 1951) 1, 13, 45, 140, and 142. |

| ⇧29 | Dodds (as n.28) iv. |

| ⇧30 | Ibid. 59–60 n.92 (a footnote to material on p.45). |

| ⇧31 | Ibid. iv. |

| ⇧32 | Rankine (as n.7) 349–50. |

| ⇧33 | We suspect that Rankine would now object also to “slave”. In a recent interview, he speaks three times of “enslaved people” rather than “slaves”: Emily Rosenbaum, “How Prof. Patrice Rankine Makes the Classics Relevant to Students,” UChicago News, July 31, 2023, available here. |

| ⇧35 | Denise Eileen McCoskey, “The Subjects of Slavery in 19th-Century American Latin Schoolbooks,” Classical Journal 115.1 (October–November 2019) 88–113. |

| ⇧36 | McCoskey cites Erik [Robinson], “‘The Slaves Were Happy’: High School Latin and the Horrors of Classical Studies,” Eidolon, September 25, 2017, still available here, which includes a photo of the relevant sentence and its accompanying illustration that he cites as coming from p.71 of the fifth edition of the Cambridge Latin Course, Book I. (Robinson means the North American edition, which was published in 2015; the fifth edition of the UK version was published only in 2022.) Some pages from a 2023 draft of the sixth edition of the North American version are available online, and the sentence in question (on p.85) has been changed to amīcī erant laetī, “the friends were happy”; there is also now a substantial section titled “Enslaved People” (92–6). |

| ⇧37 | McCoskey (as n.35) 106 and 107. (In addition, for some reason we do not understand, McCoskey herself, in a footnote about a schoolbook from 1881, available here, offers her own English translations of two Latin sentences in the book with forms of servus as “servant(s)” [104 n.74]. The book itself translates servus as “slave”; it uses the word “servant” only in parenthetical italics to show where the root has been borrowed into English – just as it translates rex as “king” and then adds “(regal)” [23 and 30].) |

| ⇧38 | Ibid. 92 and 93. |

| ⇧40 | Sasha-Mae Eccleston, “On Yearning, from the Spectacular to the Speculative,” TAPA 154.1 (Spring 2024) 331–47, at 335 speaks of “the field’s routine weaponization of rigor”. |

| ⇧41 | Eccleston & Padilla Peralta (as n.6) 201. |