Geoffrey C. Benson

Ravens on the Road to Siwa

We were about forty-five minutes outside of Marsa Matruh, a city on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast that was known as Paraetonium when Antony and Cleopatra retreated there after the catastrophe at Actium in 31 BC. My driver William, a slender, chain-smoking native of Cairo, and I were heading southwest on an empty, potholed road first over hills of shale and then through an increasingly flat Saharan landscape. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted two or three ravens pecking away at something in the desert. Was it a mirage? Or was I hallucinating? I looked out of the left windows of the ungainly tourist van again, and the ravens were still there. It was flabbergasting. Yes, brown-necked ravens are a common sight across Egypt and North Africa. So why did birds astonish me?

In Alexandria the evening before, I had reviewed Arrian’s account of Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt and subsequent journey to the Siwa Oasis in the Winter of 332/331 BC, as I was bubbling with excitement about my impending road trip. Arrian, the Roman general and friend of the Emperor Hadrian, wrote The Campaigns of Alexander the Great in the 2nd century AD, but he drew on eyewitness accounts, of varying degrees of credibility, that are no longer extant. Here’s what I read in the Elvis Suite in the Steigenberger Cecil, overlooking Alexandria’s Harbor, that would prompt me to marvel at those ravens:

From Paraetonium [Alexander] headed into the interior, to the oracle of Ammon. The route is deserted and for the most part sandy and waterless. But Alexander met with considerable rainfall, and this was attributed to the gods. The gods were also felt to be at work in the following incident: whenever the south wind blows in that country, it buries the route in sand; the markings of the route disappear and it is impossible to find one’s way, just as in an ocean of sand. No mountain, no tree, or unshifting hill rises up by which wayfarers may judge their course, as sailors do by the stars. Accordingly, Alexander’s army went astray, his guides were in doubt. Ptolemy says that two snakes, uttering sounds, advanced in front of the army, and that Alexander ordered his officers to follow them and to put their trust in the gods; the snakes led the way to the oracle and back again. But Aristoboulos says, and most other accounts agree with him, that two ravens flew ahead of the army and became Alexander’s guides (Arrian 3.3.3–6).[1]

For a moment, I was disappointed that Ptolemy’s talking snakes were not in front of our van. However, I had spent enough time studying Romans who scrutinized how eagerly the sacred chickens ate their lunch and flapped their wings to know that those ravens were auguring a favorable visit to the place I had dreamed of visiting since Middle School – the Siwa Oasis and the Oracle of Ammon-Zeus.

Most of the summer of 1998 had been a disaster. I had been stuck in bed, sick as usual, this time with a horrible, unending case of tonsillitis and then quinsy. But there was one bright spot during this lost summer of convalescing. I had been transfixed by the terrific BBC television documentary, In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great, hosted by the historian and broadcaster Michael Wood and shown on Chicago’s PBS station. At the end of the first episode, “Son of God,” Wood drives across Egypt’s Western Desert, through oceans of sand, to Siwa – what Wood describes as “a strange and magical place… [It] stands in the middle of the desert, but it’s wonderfully fertile, miraculously so. Not surprising then, that for so long people came here expecting miracles. For here on the sacred hill, the god Ammon, Zeus to the Greeks, was believed to speak directly to mankind.” Wood travels 700 km from the Nile to this oasis because it is on that rocky hill that Alexander supposedly learned who his father really was – a decisive moment in his life.

The shots in The Footsteps of Alexander the Great of trucks cutting through the Great Sand Sea, Siwa’s vast groves of date palms and crystalline springs, and the lonely Oracle Temple of Ammon were mesmerizing. I had to visit Siwa someday. I also remember how thrilling it was to see the people whom Wood befriends from Greece, Turkey, the United States, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India speak with such passion about Alexander and the ancient world.

Words of Wisdom from a Traveller from an Antique Land

My opportunity to visit Egypt and Siwa finally came during my sabbatical in Fall 2023 / Spring 2024. Right after Thanksgiving, I joined a two-and-a-half-week tour of the Nile for members of University of Chicago’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, West Asia & North Africa (ISAC for short; formerly The Oriental Institute).[3] I spent another week on my own, visiting Alexandria, the World War II battlefields of El Alamein, and finally Siwa.

While it is now fashionable to lambast tourism like this in the pages of the New Yorker, as I discovered to my horror in June 2023, I’m not that sophisticated.[4] Tourism in North Africa – in Libya and Tunisia in September 2010 right before the Arab Spring – while I toiled away on my dissertation on Apuleius, the 2nd century AD Latin author from North Africa, placed an entire swath of the Roman world in my imaginative landscape and had subtle, but significant, effects on my scholarship on Apuleius’ masterpiece, his novel known as the Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass. [5] On that trip I visited the eastern coastal region of Libya known as Cyrenaica named after the Greek colony of Cyrene on the edge of the Jebel Akhdar or Green Mountain.

I saw Cyrene and the other Greek cities of the Pentapolis – Euesperides (now Benghazi), Ptolemais, Apollonia, and Barca – not knowing at the time that it was likely Cyrene, with its great temples to Zeus Ammon and Apollo and trade with Siwa and other oases in the Libyan Desert, that disseminated knowledge of the god Ammon and the oracle throughout the Greek world.

A few weeks after reading that dismaying New Yorker article, with preparation for my Fall travel underway, one of our greatest historians of the later Roman world – Peter Brown – came to my rescue, reinforcing my ambition to explore as many of the landscapes of the Classical world as I can. Near the midpoint of his exhilarating memoir, Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History, Brown eloquently explains how his journeys in Iran in the 1970s, before the fall of the Shah, transformed him. My apologies for the long quote, but Brown’s words were a life raft for me:

My journey to Iran had been no lighthearted holiday trip. I had truly traveled. I had been infected by the huge spaces of Iran. From then, onward, spacious regions outside Europe became part of my imaginative world…

It was also a journey of the mind. By traveling to the landscapes and monuments of the Sasanian Empire, I added a whole new dimension to my knowledge of the late antique world. Hitherto, for all my curiosity, I had known about the Sasanians only through books: now Iran existed for me as a series of unforgettable images. Scrambling around monuments, and traveling over the long roads of the Iranian plateau, I somehow got the “feel” of another world, far from the Mediterranean shores of East Rome.

More important yet for the religious historian, it was a journey of the heart. For the first time, I made contact with Islam as a living religion… From then onward, the presence of Islam, in all its different forms, in past and present alike, has always claimed my attention as a weight on the heart…

I was also touched by the chanting of the Armenian church at Julfa and by the metaphysical wrangling of Mr. X, the Zoroastrian elder from Yazd. I came to feel that there was nothing strange about the desire to worship God. On my return, after a lapse of twenty years, I resumed regular attendance at a Christian church.[6]

My trip to Siwa had similar effects on my mind and heart, as I hope to convey to you. Let’s now return to the road to Siwa.

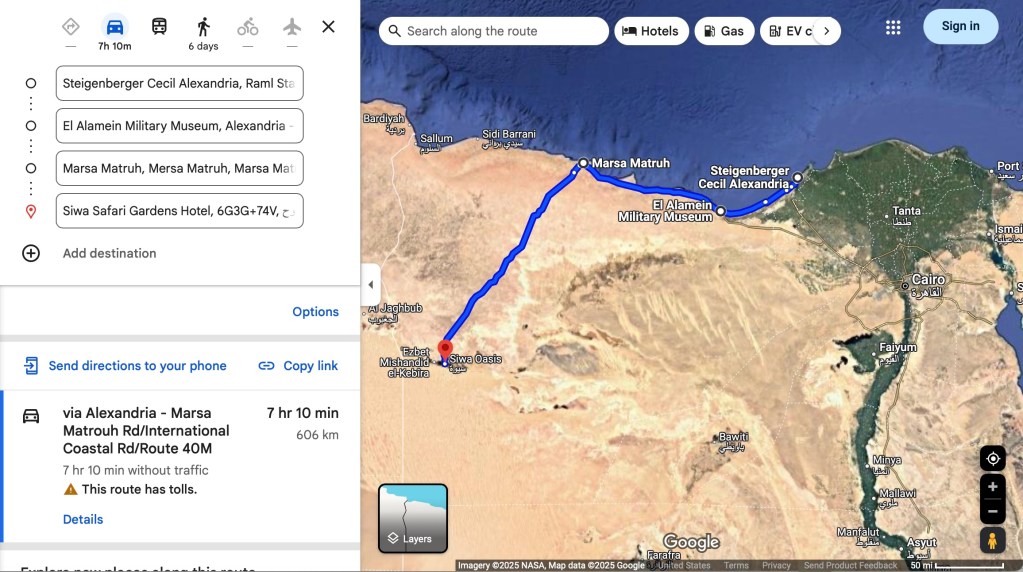

The Drive to Siwa

William and I left Alexandria at 7:15 AM on 13 December 2023, so we could visit New El Alamein, one of the new cities that President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi is building, before passing through Marsa Matruh and then driving across the desert to Siwa.

Once you get beyond the industrial area and salt fields of western Alexandria, you start passing endless beach resorts. As we neared New El Alamein, we drove on an impressive six-lane highway, flanked by gated communities, growing skyscrapers, and grand boulevards. We even spotted a new Presidential Palace. The only traffic on the road was a highspeed convoy of Maybachs. Apparently, President Sisi was in town.

We finally found what I was after: the El Alamein War Cemetery and Memorial for the Commonwealth soldiers who fought and died during one of the major battles of World War II. I walked through row after row of white headstones of men who were killed far from home in their late teens, twenties, and thirties. We drove down the road to the El Alamein Military Museum. Outside the museum, I lingered by a P40B Kitty Hawk that crashed during the battle in 1942, only to be rediscovered largely intact in the middle of the desert by oil workers in 2012.

Was the Lost Army of Cambyses also still out there in the desert somewhere? Herodotus, in Book 3 of the Histories, tells how that Persian King Cambyses sent an army of 50,000 men “to reduce the Ammonians [the inhabitants of Siwa] to total slavery and to set fire to the oracle of Zeus” (3.25.3).[7] While this Persian army was stopped for breakfast somewhere in the Western desert, “the Ammonians themselves say [that]… a strong wind of extraordinary force blew upon them from the south, pouring over them the sand it was carrying and burying them in dunes in such a way, it is said, that they completely disappeared. That, at least, is what the Ammonians claim to have happened to this army” (3.26.3). This story shadows the accounts of Alexander’s journey to Siwa, and Plutarch mentions it explicitly (Life of Alexander 26).

It was now time to head toward the deserts that swallowed up Cambyses’ army. It took a couple hours along the coastal highway to reach Marsa Matruh. We then started south into the desert, with military escort for the first half hour of driving and subsequent stops at different military checkpoints.

Security, even by the standards I’d experienced in the previous weeks, was tight. We were heading into an area the U.S. State Department categorized as “Level 3: Reconsider Travel,” due to concerns about terrorism. Tragically, in September 2015, Egyptian security forces accidentally killed eight Mexican tourists and four of their Egyptian guides who were visiting another oasis in the Western Desert.[8] The young soldiers we met were professional, but their formality was menacing, and each stop and frisk and demand for my passport was uneasy. Why was a solitary American, traveling in a massive van with his own hired driver, so interested in Siwa?

We passed through the gates to Siwa just after sunset, around 5:30 PM. It’s hard to convey just how amazed William and I both were by what we were seeing. To arrive in a verdant place, ringed with purple hills and humming with human activity, after traveling 700 km – the last 300 km on mostly empty roads crossed by the occasional solitary camel and surrounded by limitless, flat desert – is a miracle. Imagine arriving at the oasis as Alexander did, after marching across that static landscape for days on end and running out of water. We stopped at the first gas station to fill up the van and stretch our legs. Another car pulled up alongside us. What I took to be a young mother, wearing a full face covering in black and draped in a patterned shawl, sat in the back seat with several children; the driver hopped out – it was an eight- or nine-year-old boy, and he started to pump gas. We had entered another world.

Men and boys zoomed past us on tuk-tuks and motorbikes as we headed on dirt roads through town. It took us a while to find where we’d be staying the first two nights: the Siwa Safari Gardens, operated by an older German woman who ruefully described the good old days, prior to the killing of those poor Mexican tourists, when she had lots of guests. We had the place to ourselves, outside of an American Egyptian couple who resided in Chicago. Here I got my first taste of what makes Siwa unforgettable. Everywhere I looked in the courtyard outside my room there were luxuriant date palms – there are about 300,000 of them in the oasis – and beneath them lay a spring fed pool, one of the two hundred that are scattered across the oasis.

Water that I had been drinking on airplanes to Luxor and Abu Simbel in the previous weeks had come from wells 1,000 meters beneath the town. I was ready for these springs. Herodotus describes a miraculous Siwan spring whose water is cool at midday but grows boiling hot by midnight (Herodotus 4.181.2-4; Arrian 3.4.2; Curtius Rufus 4.7.22). Dinner that night – and lunch and dinner the next day – happened at Abdu Restaurant, made entirely out of palm trees, next to tables of Egyptian students from Alexandria and a few French tourists. There was the usual hum of Arabic around me, but I thought I heard something new – was it Siwi? Siwa is isolated, but much more urban than I anticipated after watching In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great.

About 25,000 people live in the area, and most are Siwi Berbers who speak their own Berber language, as I had learned from Ahmed Fakhry’s indispensable book, Siwa Oasis. Fakhry was an Egyptian archaeologist (1905–73) best known for his work in the Western Desert, and I’ll be mentioning him frequently.

William and I were exhausted by the time the food was finally served. We ate our chicken and rice quickly – I had my meeting with Zeus at 9:30 AM the next morning.

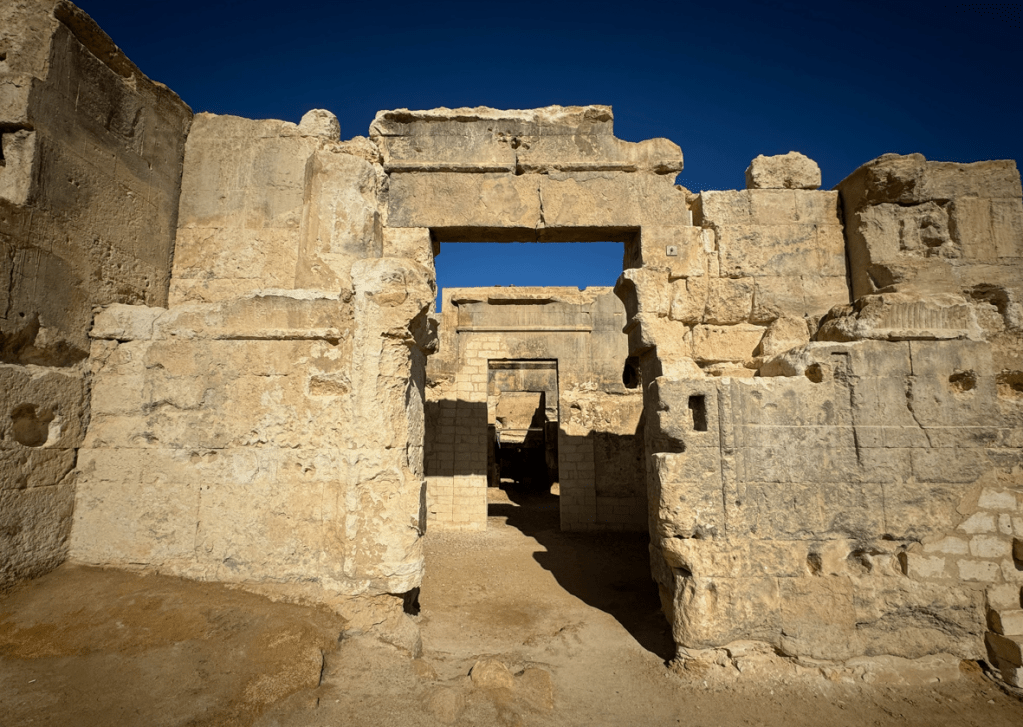

Consulting the Oracle of Ammon

It took less than ten minutes to drive to the Aghurmi Hill, the rocky acropolis of Siwa, about 75 feet high and 400 feet long, that is now mostly covered with ruined, Islamic-period mudbrick houses and a mosque. Thanks to continuous inhabitation until the early 20th century, the site was different from the descriptions of a citadel with three concentric walls in Diodorus Siculus (Library of History, 17.50.5) and Curtius Rufus (History of Alexander, 4.20–1), and the hill itself has eroded. I went up the steps with my remarkable guide Mohamed Tagga, a Siwa native with a PhD. in archaeology from Alexandria University. There it was: the Oracle Temple of Ammon. Goosebumps went up my arms and down my legs.

We sat outside the Oracle, and Mohamed told me a story about the origin of the temple that I had never heard before. Once upon a time the god Dionysus was marching his army through the Libyan desert on his way to conquer India. Exhausted and thirsty, he prayed to his father Zeus. A ram appeared in the desert. Dionysus followed it to a place where the ram scratched the ground with its foot. A spring flowed out from the spot, and Dionysus built a temple to Zeus there, giving the cult statue ram’s horns and calling his father Ammon from the Greek word for sand, hammos. Mohamed followed up this myth by insisting that Greeks from Cyrene, in collaboration with princes of Siwa, had built the Oracle Temple in the Sixth Century BC. In 1938, Fakhry – that archaeologist I mentioned earlier – had been able to read the cartouche on the right wall of the cella of the temple: the figure making offerings to the gods is the Twenty Sixth Dynasty Pharaoh Amasis (570–526 BC), the last major ruler before the Persian conquest of Egypt. I could barely see the relief of the pharaoh, but I couldn’t spot Amun and the other seven deities facing him that Fakhry describes in his book. On the left wall, directly opposite to Amasis, instead of following behind him, is the local ruler, “the Prince of the Two Deserts, Sutekhirdes, son of Leloutek” – a sign of the autonomy of Siwa and the surrounding Cyrenaican and Egyptian deserts in this period.

The stories that Mohamed told me next were more familiar. The Greek poet Pindar had learned about Ammon while in residence in Cyrene and popularized the god in the Greek mainland. In Cyrene Pindar wrote the 4th Pythian for King Archesilaus IV and a hymn to Ammon from which just the opening line survives, capturing the god’s complex identity, “O Ammon, lord of Olympus.”[9] Prominent Spartans and Athenians, Mohamed told me, consulted the Oracle in the 5th and 4th centuries to discover how military campaigns or political projects would pan out, among them Cimon and Alcibiades of Athens and Lysander of Sparta. Mohamed finished with the story of Alexander’s consultation of the oracle, on which more in a moment. Siwa was a major oracle for the Greeks, on par with the Oracles to Zeus at Dodona and Olympia, but it was also important to the Libyan populations in the Kingdom of the Two Deserts and Egyptians on the Nile.

We got up from the bench and walked to the entrance of the Oracle Temple. The Ammoneion looked nothing like a Greek temple. Its layout – a court, followed by two halls that lead to the sanctuary or cella, to the left of which is another room, identified as Hall of Prophecy, and to the right of which runs a “Secret passage” – didn’t resemble the massive Egyptian sanctuaries along the Nile that I had visited in the previous weeks either. The appearance and pitch of each of the four doorways, however, made me think of the enormous pylons at Medinet Habu and Edfu. I could see traces of half-fluted Doric columns at each side of these doors, but as Fakhry explains these may come from a later renovation. Why had Mohamed insisted that Greeks had built this unusual temple? The story about the foundation of the Oracles to Zeus at both Siwa and Dodona in Greece that I knew from Herodotus (2.54–5) traced their origins to Thebes, the city in Upper Egypt where the huge temples of Amun at Luxor and Karnak stand.

I naively chalked Mohamed’s story about the Dionysian and Greek origin of the Oracle up to politics. In 1820, Mohamed Ali annexed Siwa, but Egypt’s control over the oasis was tenuous, as I learned from Fakhry’s book. Siwi Berbers had their own culture and language, and they chafed to be under Egyptian control. For example, after King Fuad I’s visit in 1928, the Egyptian government with help of some Siwan tribal elders tried to eradicate Siwa’s famous pederastic traditions and informal same-sex marriage rituals – and this was resisted. I understood Mohamed’s story in this broader political context. However, I did not realize at the time that his story about Dionysus’ foundation of the Oracle is attested in two different ancient sources – in Servius’ Commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid, specifically the entry on Dido’s Libyan suitor, Iarbas (4.196), and in a rationalized version of the myth first told by the Alexandrian scholar, Dionysius Scytobrachion (FGrH 32 F8), that is transmitted in Diodorus Siculus’ Library of History 3.73. The god Dionysus had a strong presence in Alexandria, so I could perhaps see the faint traces of a local mythological tradition in Mohamed’s tale.[10] I would also later learn that excavations by the German Institute of Archaeology in the 1980s uncovered Greek masons’ marks on the palace and walls of the well on Aghurmi. Accordingly, the excavator, Klaus Kuhlmann, argued that the architects of the temple were Greek and likely from Cyrene, but he notes that the temple’s design “is rather unique”.[11]

It was now time to meet Zeus after so many years and so many tribulations. Mohamed stood at the threshold of the sanctuary to invite me into the presence of the god. Readers – I imagine you have a pressing curiosity about what was said, done, and seen within. However, to paraphrase one of my favorite authors, the novelist Apuleius, I’d tell you if it were allowed and you’d hear if it were permitted – “But your ears and my tongue would provoke equal offence: my tongue for its impious lack of self-control, your ears for their reckless curiosity” (Met. 11.23). I don’t want to torment you, though, so I’ll say a few words about Alexander the Great’s consultation of Ammon, instead.

Alexander’s visit to Siwa was one of the most momentous events in his life, discussed in the works of nine different Alexander historians. These writers offer contradictory accounts of what happened. Modern scholarship has not reached a consensus, despite endless debate, about why Alexander paused his campaign against Darius to make the harrowing journey to Siwa, what happened inside the Oracle Temple and what he asked the god, and how the experience shaped Alexander’s outlook and subsequent behavior. Did he come to think he was a god? In addition, was Alexander coronated as pharaoh in Memphis before he set out to Siwa or is this just another tall tale from the Alexander Romance? And when did Alexander found Alexandria (if he did this at all), before or after he consulted the oracle? I’m not going to get into the scholarly weeds; the Further Reading section at the end of this essay will help you do that. But I’d just like to draw your attention to just one of the fascinating differences in the sources.

Several writers from the so-called “Vulgate Tradition” profess to know what Alexander asked the Oracle and how Ammon replied. Justin, for instance, claims Alexander “bribed the priests to give the responses he wanted” to his questions about the identity of his real father, whether he had avenged Philip II, and whether he would conquer the world (Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus,11.11.6–11).[12] Diodorus Siculus says Ammon answered Alexander in a traditional Egyptian fashion: the cult image of Ammon is “encrusted with emeralds and other precious stones,” and it “answers those who consult the oracle in a quite peculiar fashion. It is carried about upon a golden boat by eighty priests, and these, with the god on their shoulders, go without their own volition wherever the god directs their path” (17.50.6–7).[13]

However, this testimony is contradicted by two other authors. Our earliest Alexander historian, Callisthenes, was Alexander’s court historian until he opposed Alexander’s adoption of Persian practices and was implicated in a plot against Alexander in 328 BC. In Callisthenes’ version of events, as related by Strabo (c.64 BC–AD 21), Alexander entered the Oracle by himself, so no one outside could hear what he asked Ammon and what he learned:

The priest allowed the king alone to enter the temple in his customary attire, while the others had to change their clothing, and everyone else listened to the oracle from the outside, except for Alexander, who heard it from inside. Despite the fact that the oracular responses were not, as at Delphi and Branchidae, given verbally but rather by means of nods and signs (as Homer says, the son of Cronus spoke and nodded assent with his dark brows, the oracle giver being the equivalent of Zeus), nevertheless the oracle giver explicitly told the king that he was the son of Zeus. (Strabo, Geography C818 C, 6-14; 17.1.43 = Callisthenes FGrH / BNJ 124 F14a).

When exactly was Alexander told that he was the son of Zeus? If he had already been crowned pharaoh or the priests perceived him in this guise, they would have referred to him as a son of Amun-Ra as soon as he stepped foot on the Aghurmi hill.

Arrian – the other representation of the so-called “Official Tradition,” in that his two major sources, Aristobulos and Ptolemy, were Alexander’s companions – is similarly reticent about Alexander’s meeting with Ammon. Arrian alleges Alexander visited Siwa “to trace his own birth to Ammon, just as the myths trace the births of Perseus and Herakles to Zeus” (3.3.2). But Arrian says next to nothing about the consultation: “Alexander marveled at the place and posed his questions to the god Ammon. When he heard what his heart desired (as he said), he led the army back to Egypt” (3.4.5). The conclusion that the eminent historian Ernst Badian drew from Callisthenes and Arrian is that “We simply cannot tell what happened” inside the Oracle Temple.[14]

It would be malpractice to neglect Plutarch’s version of these events. The biographer shares an anecdote about one of the most consequential grammatical mistakes in history – and a reminder to all students learning Greek why studying accents and memorizing genders of nouns are such rewarding activities:

Some writers say that the prophet wanted, out of politeness, to address Alexander in Greek with the words “O paidion” (“My son”), but, not being a Greek-speaker, made a mistake with a sigma ending and said “O paidios” instead, substituting a sigma for a nu. Alexander, they say, was delighted with this slip in pronunciation, and word got out the god had addressed him as the son of Zeus, pai Dios. (Life of Alexander 27.9–10).

Plutarch, like the Vulgate authors, records the questions that Alexander allegedly asked Ammon (27.5–7), but then adds a new detail, more in line with Callisthenes and Arrian: “Alexander himself in a letter to his mother says that he received some secret oracles which he would tell her and her alone when he returned” (27.8). Whatever Alexander heard died with him: he never returned to Macedonia and never saw his mother Olympias again.

I exited the sanctuary of Ammon with my own lips sealed. There was no more time to linger – we had much more to see.

More Sightseeing in Siwa

We drove about half a kilometer south, along the ancient processional way to the Oracle, to the contra-temple of Umm Ubayda.

Mohamed ascribed this ruined edifice to the last pharaoh of independent Egypt, Nektanebo II, who reigned from c.358–340 BC and is one of Alexander’s reputed fathers in the Alexander Romance (he sleeps with Alexander’s mother, Olympias, while disguised as Ammon, 1.7). He mentioned that another Prince of the Two Deserts – Wenamum – dedicated the temple: this prince is shown in relief, kneeling in front of Ammon, on the building’s only surviving wall.

We looked north, back toward Aghurmi, over piles of stone blocks that once made up the building. Some of the blocks were enormous. It must have been an impressive place in its day[15]

Our next destination was Gebel al-Mawta, the “Mountain of the Dead”, a conical hill close to the modern town’s center that was the ancient necropolis. Two thousand burials, Mohamed said, had been uncovered, and everywhere you looked you could see bits of human bone.

Four tombs, with paintings, have been excavated – three of which were discovered in 1940 and cleaned by Fakhry. We visited the Ptolemaic-era tomb of Si Amun, admiring the paintings of a bearded Si Amun and his son. Mohamed, on Fakhry’s authority, stated that Si Amun’s father was likely a Greek from Cyrene and his mother an Egyptian.

Ten minutes later we were walking up the streets of medieval Siwa, past a mosque and empty multistory homes. This was the Shali fortress (Shali means “town” in Siwi). The fortress, Mohammad told me, was built in 1204 in response to nomadic raiders after Siwa’s dates, olives, and salt. The population had been reduced, and the Siwan Manuscript – a local history of Siwa in possession of one of the families of the oasis – states that the surviving 40 men from seven families built the strong fortified wall. In the Middle Ages, Siwa was an important stop for caravans and a center of the slave trade. The buildings around us were now in ruins – many were abandoned in 1926 after an unusual three-day rainstorm. But the view was terrific. I got a feel for the landscape of the oasis, that stark contrast between the empty waves of quiet desert sand to the south and the bustling, loud oasis. I looked east and saw Aghurmi hill peeking through the groves of date palms – from this vantage point, it looked like the acropolis of a polis. And then I turned west, towards the modern town of Siwa, Siwa Lake, and Mount Jafaar.

Our last stop on the circuit was a surprise: the Library of the Three Black Lions, nestled just outside the fortress.[16] This small library and research center for the promotion and study of the Kingdom of the Two Deserts – the semi-independent Libyan Kingdom of Sutekhirdes and Wenamun – was founded by an Italian ex-oil engineer, Sergio Volpi, and his French wife, Pascale Bellamy, who has published a novel about the mythical city of Zerzura in the deserts around Siwa.[17] Sergio showed me around the library. Here were all the books I needed to read about Siwa and the Kingdom of the Two Deserts. This was a labor of love, and it looked like the people of Siwa were taking full advantage of the books, the computers, and the cool study spaces. I would later learn from a book Sergio recommended, Adventures in the Libyan Desert (1849), that its author, the English traveler Bayle Frederick St John (1822–59), had also seen ravens when his caravan of camels lost its way to Siwa in 1847. What I’ve always found so exciting about studying Classics are these fortuitous meetings with people from my discipline’s past – figures who approached the history and literature of the ancient world from very different circumstances and with very different preoccupations than my own but who share my enthusiasm.

Later that afternoon, we drove to Fatnas Island to drink mint tea and watch the sunset. We sat with students from Marsa Matruh and Alexandria who were spending a long weekend at the Oasis.

Mohamed talked with William and me about his adventures in the desert. He had searched for those waypoints marking the route between Marsa Matruh and Siwa that Arrian and Plutarch mention. He had found inscriptions from the reign of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius 17km west of Siwa in the desert. Music was playing, and the students were animatedly talking with each other as the sun slipped below the horizon. It had been one of the great days of my life. On that momentous morning Ammon had set me on firm ground and shown me the path ahead. It was all possible because of that awful case of quinsy. That documentary about Alexander by Peter Brown’s student, Michael Wood, had sparked my imagination and fed my growing interest in ancient history and the legends and stories about Alexander’s world.

Goodbye to Siwa

Siwa is extraordinarily beautiful. The next morning, we drove east, across an empty lakebed, to the Salt Lakes of Siwa – turquoise pools with extremely high salinity, lined with salt crystals that I could palm, crystals Arrian describes with wonder (3.4.3–4).

Over coffee, Mohamed told William and me about an Instagram influencer from LA who had travelled all the way to Siwa just to have photos taken of herself floating in one of the pools. Who was I to judge?

After a brief stop back in town to register with the military police at Cleopatra’s Spring (never visited by Cleopatra herself), we said goodbye to Mohamed.

We drove west, along the northern edge of Siwa Lake, to my new hotel, the Adrère Amellal Eco-Lodge, on an isolated island on the western side of Siwa Lake and perched at the base of the “White Mountain” (after which the resort is named in Siwi). It was the perfect spot to unwind after four weeks of constant movement, and it made those resorts portrayed in the HBO series The White Lotus look like the worst pay-by-the-hour motels you’ve ever been forced to stay in.

There was no electricity, no cellphone reception, and no other guests in this “labyrinthine fortress-village” built entirely out of local materials in traditional Berber fashion. My house was made of kershef – a traditional building material comprised of sun-dried rock salt and mud,which acts as a natural insulator – and that was a godsend after two clammy nights in the Safari Gardens. The resort’s pool was one of Siwa’s springs – and I jumped right in. The murky water was cold, and bubbles popped to the surface.[18]

In the late afternoon I scrambled up the White Mountain, which loomed over my private village. I had the mountain and its winds all to myself. But the breathtaking views thwarted plans to reflect on the past four weeks. On my left and to the south were the mammoth, endless dunes of the Great Sand Sea. Behind me and to the east was Lake Siwa; Fatnas Island, the Shali Fortress, the Oracle temple, and Jabal Darkour glowed in the fading sunlight. But the new scene in front of me to the west of inselbergs, streaked with salt and surrounded by more lush palm groves and gardens, was mesmerizing. I sat along the rim of the White Mountain and just watched the Great Sand Sea slowly swallow the sun.

That night beeswax candles and braziers illuminated Adrère Amellal. Now it was the time for contemplation and delicious Berber food before a crackling fireplace in what must be one of the great rooms in the world.

I did not want to leave Siwa. “Who knows,” as Horace puts it in one of his greatest poems, “whether the gods above are adding the times of tomorrow to the sum of today?” (Odes 4.7.17–18). Alexander never returned to Siwa, although Ammon was a constant presence in his life thereafter. The god’s importance to him is most evident following the sudden death of his friend Hephaestion at Ecbatana in what is now Iran in autumn 324. Alexander’s grief, Arrian says, matched that of Achilles for Patroclus (7.14.1–7). In the moment of his greatest despair, Alexander sent an embassy to Ammon “to ask the god whether it was permissible to sacrifice to Hephaestion as to a god, but the oracle would not allow it” (7.14.7). No one, however, followed through on Alexander’s deathbed instructions in Babylon in 323, as reported only in Curtius (10.5.4), to bury his remains at Siwa.

Ammon granted me one last, unforgettable tableau. On the morning of my departure Aurora stretched her saffron and tangerine fingers over Siwa Lake and left the Shali Fortress, the Mountain of the Dead, and the Oracle itself etched on the horizon in black.

No crows or talking snakes waited for William and me as we drove along the northern rim of Siwa Lake a little after 8:00 AM and I looked back at the White Mountain.

Ammon had a different omen in store for me that day – a symbol of patience, endurance, and determination in the face of harsh circumstances. A few hours into our long trip back to Cairo, after yet another stressful stop and frisk, William suddenly had to slow the van down to a crawl: a caravan of camels plodded across the road and temporarily blocked our path.

Geoffrey Benson is Associate Professor and Chair of the Classics at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. He is author of Apuleius’ Invisible Ass: Encounters with the Unseen in the Metamorphoses (Cambridge UP, 2019).

Further Reading

Ancient Literary and Epigraphical Evidence for Alexander’s Visit to Siwa

Nine passages, usefully enumerated by Agut-Labordère (2024) 308, describe Alexander’s journey to Siwa and consultation of the Oracle of Ammon, and they are listed here in chronological order:

Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History 17.49.2-51

Strabo, Geography C813-814 (17.1.43) = Callisthenes FGrH 124 F14a

Quintus Curtius Rufus, The History of Alexander 4.7.5-4.7.32

Plutarch, Life of Alexander 26-27

Arrian, Anabasis 3.3.1-3.4.5

Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus 11.11

Pseudo-Callisthenes, Alexander Romance 1.7, 1.30

Fragmentum Sabbaiticum FGrH 151 F1.9-10

Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 12.537e-f (12.53) = Ephippus of Olynthus FGrH 126 F5

These authors range from the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD, but they all build on and sometimes explicitly cite and paraphrase eyewitness accounts that were written in Alexander’s lifetime (356–323 BC) or shortly thereafter but are now no longer extant. For example, Strabo (c.64 BC–AD 21) is paraphrasing Callisthenes of Olynthus (c.360–328 BC), the nephew of Aristotle and court historian of Alexander. Arrian (c.AD 85–160), the other representation of the so-called “Official Tradition,” cites two eyewitnesses who served with Alexander the Great: Aristoboulos (c.380–301 BC) and Ptolemy I Soter (c.365–283 BC). Finally, the authors of the so-called “Vulgate Tradition” – Diodorus Siculus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, and Justin – share a source by Clitarchus of Alexandria (late 4th or early 3rd century BC) that has not survived.

The abbreviation FGrH in the list above stands for the collection of fragments from works by Ancient Greek historians that have been lost – Felix Jacoby (ed.), Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker (Berlin, 1923–58. These fragments have now been published online, with new English translations and commentaries, as Brill’s New Jacoby (BNJ), edited by Ian Worthington.

A bilingual inscription from the small temple to Ammon in the Bahariya oasis, 420km east of Siwa on a caravan route to Memphis, adds a further layer of complexity to the divergent pictures in the literary sources. Photographs, illustrations, transcription, and French translation of this inscription can be found in Francisco Bosch-Puche’s article “L’autel du temple d’Alexandre le Grand à Bahariya retrouvé,” BIFAO 108 (2008) 29-44.

The Greek text reads, “King Alexander to his father Ammon.” This is corroborated much more fully in the hieroglyphic inscription with Alexander’s five pharaonic names. Bosch-Puche argues Alexander himself set up the inscription on his way to Memphis, after consulting Ammon at Siwa. If this is so – and from what I’ve seen this argument is controversial – it would have many ramifications: Alexander would have founded Alexandria before arriving in Siwa; he would have heard there that Ammon was his father; and he would have taken the desert route back to Memphis, as Ptolemy stated in his account (Arrian 3.4.5).

Here are the English editions of the literary sources that I like best and from which the translations in this essay derive:

Cinzia Bearzot, “Fragmentum Sabbaiticum (151),” in Ian Worthington (ed.), Jacoby Online. Brill’s New Jacoby, Part II (Brill, Leiden, 2017).

O.H. Oldfather (transl.), Diodorus Siculus: Library of History (12 vols, Loeb Classical Library, Heinemann, London/New York, 1933).

S. Douglas Olson (transl.), Athenaeus: The Learned Banqueters, Volume VI: Books 12-13.594b (Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010).

Sarah Pothecary (transl.), Strabo’s Geography: A Translation for the Modern World (Princeton UP, NJ, 2014).

James Romm (ed.) & Pamela Mensch (transl.), The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander (Pantheon, New York, 2010).

Richard Stoneman (transl.), The Greek Alexander Romance (Penguin, London, 1991).

Robin Waterfield (transl.), Plutarch: Greek Lives, A Selection of Nine Greek Lives (Oxford UP, 2008).

John Yardley (transl.(, Quintus Curtius Rufus: The History of Alexander (Penguin, London, 1984).

Waldemar Heckel (ed.), Justin: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Vol. I Books 11–12: Alexander the Great (Oxford UP, 1997).

Further Reading: Some Highlights from the Modern Scholarship

Below is a tiny selection from the exciting and extensive scholarship on the Siwa Oasis and the Kingdom of the Two Deserts, the archaeology and history of the Oracle of Ammon, and Alexander’s visit to Siwa in winter 332/331 BC.

Damien Agut-Labordère, “Alexander, ‘Prince of the Two Deserts’: the geopolitical significance of the trip to Siwa,” in A. Wojchiechowska & K. Nawotka (edd.), Legacy of the East and Legacy of Alexander (Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2024) 303–22.

Ernst Badian, Collected Papers on Alexander the Great (Routledge, London, 2012).

Roger S. Bagnall & Dominic W. Rathbone (edd.), Egypt from Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2005).

A.B. Bosworth, “Alexander and Ammon,” in K.H. Kinzl (ed.), Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean in Ancient History and Prehistory: Studies Presented to Fritz Schachermeyr on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday (De Gruyter, Berlin/New York, 1977) 51–75.

Ahmed Fakhry, The Oases of Egypt I: Siwa Oasis (The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 1973).

Timothy Howe, “Alexander and Egypt,” in Daniel Ogden (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great (Cambridge UP, 2024) 82–96.

Klaus P. Kuhlmann & William M. Brashear, Das Ammoneion. Archäologie, Geschichte und Kulturpraxis des Orakels von Siwa (Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, 1998).

Klaus P. Kuhlmann, “The realm of the ‘Two Deserts’: Siwa Oasis between East and West,” in F. Förster and H. Riemer (edd.), Desert Road Archaeology (Heinrich-Barth-Institute, Cologne, 2013) 133–66.

Nikolaos Lazaridis, “Amun-Ra, Lord of the Sky: a deity for travellers of the Western Desert,” British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 22 (2015) 43–60.

H.W. Parke, The Oracles of Zeus: Dodona, Olympia, Ammon (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1967).

Cassandra Vivian, The Western Desert of Egypt: An Explorer’s Handbook (The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2000).

Ulrich Wilcken, “Alexanders Zug in die Oase Siwa,” Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Phil.-Hist. Klasse 30 (1928) 576–603.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Listed in the Further Reading section at the end of this essay are the major ancient literary accounts of Alexander’s visit to Siwa, with references to accessible editions in English from which all the translations in this essay derive. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | All the photos that accompany this essay were taken by Geoffrey C. Benson. |

| ⇧3 | More information about the excellent ISAC tour to Egypt, which has recently been led by the illustrious Egyptologist, Emily Teeter, can be found here. |

| ⇧4 | Agnes Callard, “The Case Against Travel,” New Yorker, 24 June 2023, available here. |

| ⇧5 | Geoffrey C. Benson, Apuleius’ Invisible Ass: Encounters with the Unseen in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses (Cambridge UP, 2019). |

| ⇧6 | Peter Brown, Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History (Princeton UP, 2023) 444. |

| ⇧7 | The best edition of Herodotus, from which this translation derives, is Robert Strassler (ed.), The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, transl by Andrea L. Purvis (Pantheon, New York, 2007). |

| ⇧8 | Merna Thomas and David D. Kirkpatrick, “Egyptian Military Fires on Mexican Tourists During Picnic,” The New York Times, 14 September 2015, available here. |

| ⇧9 | Pindar, fragment 36. Ptolemy I had Pindar’s hymn inscribed on a stele next to the temple’s entrance, as Pausanias reports (9.16.1), to thank Ammon for telling the Rhodians to honor him as a god (Diodorus Siculus 20.100.3). |

| ⇧10 | I came across the sources for Mohammed’s story about Dionysus while reading Parke (1967), 234–5. For Dionysus’ presence in Alexandria, see Hugh Bowden, “Religion,” in The Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great, edited by Daniel Ogden (Cambridge UP, 2024) 237. |

| ⇧11 | Kuhlmann (2013) 156–7. |

| ⇧12 | You’ll find roughly similar accounts in Diodorus Siculus (The Library of History 17.51.1–4), Curtius Rufus (The History of Alexander 4.7.25–8), and Plutarch (Life of Alexander 27). |

| ⇧13 | Also see Curtius Rufus 4.7.23–4. This method of oracular consultation – asking Amun questions as the god is transported on a “bark” carried by a team of wab priests during a festival and with the movement of the bark signifying the god’s answers – is attested in the reliefs at the temple of Amun in Luxor and in The Brooklyn Oracle Papyrus (now in the Brooklyn Museum) from the reign of Psammatichus I (651 BC) (47.218.3a-b). For further details about Egyptian oracles, see Emily Teeter, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt (Cambridge UP, 2011) 104–12. |

| ⇧14 | Badian (2012) 255–6. |

| ⇧15 | According to Fakhry (1973), an 1811 earthquake caused major damage to Umm Ubayda, and in 1897 an “ignorant” government official dynamited what was left to build a staircase in a police station and his own house. Drawings by the German consul Heinrich Menu von Minutoli, who visited in 1820, give us some sense of what the temple once looked like. His drawing of the reliefs on one of the destroyed walls, reprinted by Fakhry, shows Wenamun, with a feather in his hair, standing in front of a similarly attired deity. Fakhry (1973, 170) speculates that “this is probably the ancient god who was worshipped at Siwa before the supremacy of Amun in this oasis. His name is not preserved; and a similar scene does not appear anywhere else on the monuments of Siwa.” |

| ⇧16 | More information about the Library of the Three Black Lions and The Association for the Knowledge of the History of the Kingdom of the Two Deserts can be found here. |

| ⇧17 | Pascale Bellamy, Le Temple caché de Zerzura ou l’épopée de la pierre d’Amon (Douro, Chaumont, 2021). In the 1930s, the Hungarian adventurer László Almásy searched for Zerzura in the Western Desert, and he served as the model for the protagonist in Michael Ondaatje’s 1992 novel, The English Patient, and subsequent film adaptation. |

| ⇧18 | Here is the website for Adrère Amellal, in case you’d like to book a room. It’s full of enjoyably breathless reviews: “A paradox in process, mingling the asceticism of a Cistercian monastery, the luxuries of a Turkish seraglio, and the whimsy of a Cape Cod sandcastle” – “At night it is so quiet that you begin to hear the stars” – “The greatest luxury is the silence of the desert.” |