Barry Strauss

King Herod the Great (c.72–c.4 BC) is perhaps best known in European history for his role in the story of the birth of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 2. As Matthew recounts, Herod instructed the three Magi, visiting from Persia, to inform him of the whereabouts of Jesus (“He that is born King of the Jews”), an order which they promptly ignored. After the birth of Jesus, in one of his final acts, the aged King orchestrated the famous Slaughter of the Innocents.

In the following selection from Professor Barry Strauss’s new book Jews vs. Rome, we chart Herod’s rise to power, when he befriended some of the most famous in ancient history – Cleopatra, Mark Antony, and Octavian.

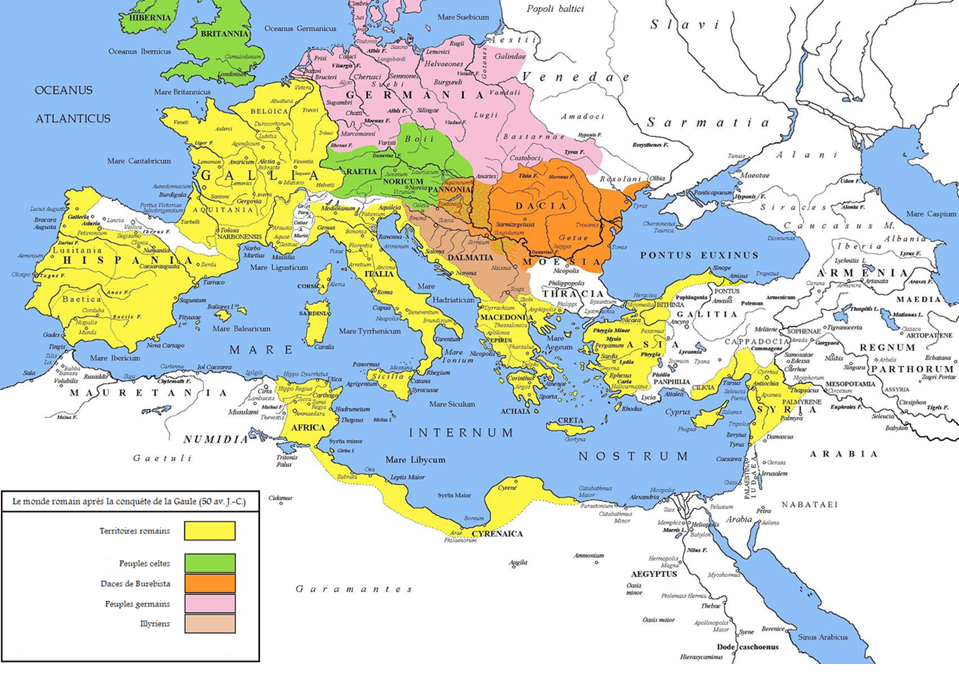

Herod was the son of a low-born chief palace official in the tumultuous kingdom of Judea. At the time, Judea was not a Roman province but a client kingdom which served as a buffer state between Rome and the Parthians – a Persianate empire to the east, and Rome’s only serious geopolitical rival. In 46 BC, Herod was appointed as the governor of some of the northern regions of the kingdom.

Herod was a fierce leader of the Rome-collaborating faction of the hellenized upper classes of local Jews, and demonstrated his loyalty by crushing a grassroots local uprising. For this, he was resented by the freedom-fighting populists who saw Rome as an oppressive regime of idolaters.

Our story picks up in medias res in 40 BC. The Parthians, exploiting Roman civic turmoil, rode into Jerusalem, first as mediators in a dispute, and then as “liberators” of the Jews. They lured Herod’s brother into their power with the promise of negotiations – but it turned out to be a trap. Herod’s brother committed suicide rather than face torture. Herod, on the other hand, chose otherwise:

Herod took his future mother-in-law’s advice and left Jerusalem at night with armed loyalists and female family members. Parthian and Jewish forces went after them. After depositing his family members in safety, Herod got away, fighting and negotiating at every step. He probably cut an impressive figure. He was every inch a soldier, strong and athletic, and a good hunter, too. After a failed effort to get support from his mother’s people in Petra, he turned westward.

Rome’s Man in Jerusalem

Herod went first to Egypt. Queen Cleopatra received him warmly, because they had a common ally, Mark Antony. Antony was one of the triumvirs who ruled the Roman Republic. As the name suggests, triumvirs were three men, but only two of them mattered, Antony and Octavian. Both were connected to Rome’s greatest general and late dictator, Julius Caesar, assassinated on the Ides of March, 44 BC. Antony was Caesar’s distant cousin and one of his chief lieutenants. Octavian was Caesar’s grandnephew and designated heir. Antony ruled the eastern half of the Roman Empire and Octavian most of the West. Both men were ambitious and ruthless leaders. Antony was a better soldier, Octavian a more cunning strategist.

Cleopatra, Antony, and Octavian each radiated charisma. Cleopatra was highly seductive but, to judge from coin images, more because of her charm than her looks. Her allure was magical. She had the dignity of an ancient royal family plus the wit and brilliance of a polymath. As queen she was a goddess on earth, but she was not above cracking a dirty joke or slumming at night in the poorer parts of town. An audacious and cunning strategist, she won as lovers in turn the two most powerful men in the Roman world, Julius Caesar, allegedly the father of her eldest son, and Antony, who was her ally in love and war.

Herod had met Antony years earlier, when Antony fought in a Roman army sent to Judea to suppress a rebellion against the pro-Roman faction led by Herod’s father. Herod impressed him enough to be named in due course “tetrarch”, that is, ruler of Galilee.

Cleopatra coveted Judea. It had once been an Egyptian possession, in an earlier century, and she wanted it back. Aware of the queen’s agenda, Herod accepted Cleopatra’s hospitality, but left Egypt as quickly as possible. He took ship in midwinter, a dangerous season for sailing. After a rough journey, Herod reached Rome in late autumn 40 BC.

Rome was the right place for Herod, and not just because of his family’s connections there. Herod and the Romans had a culture in common, and that culture was Greek. Greek was not just the main language of the Roman East; it was the great language of ancient elite culture from Hispania to Mesopotamia. Roman nobles learned Greek the way Russian nobles in the tsarist era would learn French. Herod spoke Greek. His very name was Greek and came from the word herōs, “hero”. Later, when he was in power, the Jew Herod surrounded himself with Greek intellectuals.

His mission in the capital was to see Antony. The ruler of the East was back in Italy to patch up differences with Octavian, with whom he had almost gone to war. Antony didn’t waste time after hearing Herod’s story. He decided then and there to make Herod not just tetrarch but king. On the face of it this was a nonstarter. Few Jews would accept a commoner and an Idumean on the throne. Others wanted no king at all, preferring rule by a council of priests and notables. The Roman Senate, for its part, liked to give the nod to a member of the reigning family, whenever the Senate had to approve a foreign king.

Herod nevertheless served Rome’s purposes. Precisely because he had so many enemies at home, he would depend on Rome; no danger of him turning to Parthia. As an old acquaintance of Herod, Antony felt that he knew the man. Octavian remembered Herod’s father’s support for Caesar. Both Romans found Herod’s dynamism impressive. Octavian convened a meeting of the Senate, where, after various speeches, Antony sealed the deal. He put the case for Herod bluntly: he told the senators that “it was an advantage in their war against the Parthians for Herod to be king”. Judea was a problem; Herod was the solution. The Senate voted unanimously in favor of the motion.

Antony and Octavian walked out of the Senate House with Herod between them. The two consuls and Rome’s public officials led a parade up to the Capitoline Hill nearby. There, the newly proclaimed king of the Jews took part in a sacrifice to the pagan deity, Jupiter, the chief god of Rome. A copy of the Senate’s decree in favor of Herod was then deposited in the state archive.

To cap a day to be remembered, Antony gave a banquet in Herod’s honor. It is doubtful that the cuisine was kosher. Never in history had a king of Israel been named in stranger circumstances.

A Throne, If You Can Keep It

Herod headed home and gathered an army to fight for his throne, but with Antigonus he faced an enemy who had the support of the Parthians and of most Jews, who considered Herod a usurper.

Fortunately for Herod, Antony and his generals launched a major effort to drive the Parthians back east beyond the Euphrates. The Roman counteroffensive inflicted defeat after defeat on the Parthians. Finally, in 38 BC, they met the main Parthian force in northern Syria. They lured the Parthian cavalry into riding uphill. Roman heavy infantrymen and slingers drove the enemy back downhill and into confusion and disorder. Suddenly, Pacorus the Crown Prince himself fell in the thick of fighting. Some of his men tried to recover his body, but they, too, were killed. At that point, the rest of the Parthian army broke and ran. The victorious Romans sent a message to the various cities of Syria that had been playing a waiting game. That message was crude but clear: it was Prince Pacorus’ severed head. The province now fell into line back behind Rome.

At the same time, the Romans sent troops to help Herod, but they were poorly led and ill-motivated. Herod was made of sterner stuff: he defeated [the rival Jewish leader] Antigonus in battle, but an insurgency quickly sprang up. For two years he fought a frustrating campaign up and down the country.

Outlaws and bandits roamed the countryside in these disordered times; at least Josephus refers to them as bandits: presumably some were insurgents and supporters of Antigonus. Herod faced a battle with the so-called bandits in Galilee. Herod subdued them. Antony gave Herod one of his most trusted generals to fight in Judea: Gaius Sosius, recently appointed governor of Syria and Cilicia.

In autumn 38 BC, Herod and Sosius set up their camp outside Jerusalem. In spring 37 BC, they attacked the city in force. Antigonus and his troops defended the city vigorously, but they were no match for the combined forces of Herod and the Roman legions, who took the city after a siege of more than four months.

The victors went on a rampage, looting property and killing everyone in their path, whether soldier or civilian, male or female, young or old. The legionaries were eager to enter the Temple and its Holy of Holies, in imitation of Pompey’s sacrilege. Herod asked Sosius to stop the slaughter, or Herod would be king of a desert. Sosius shot back, saying in effect that soldiers will be soldiers. Herod finally had to buy the Romans off, with payments to every soldier out of his own pocket. He made sure to give the officers extra and to hand over a king’s ransom to Sosius, enough so that he could donate a golden crown in the Temple.

A defeated Antigonus threw himself at Sosius’ feet, begging for mercy. Sosius laughed at Antigonus uproariously, called him a girl, “Antigone”, put him in chains, imprisoned him, and shipped him off to Antony in Syria. Antony wanted to send Antigonus to Rome, but Herod sent a large bribe and convinced Antony to execute Antigonus. Antony took the money and had Antigonus killed in a humiliating manner – the sources disagree about the details – that shocked public opinion.

Herod settled another score once he had the throne. He had all the members of the Sanhedrin executed, no doubt in retaliation for the humiliation of having put him on trial for murder of the rebel Hezekiah. He spared Samias, who had criticized the trial and predicted Herod’s rise to power and ultimate vengeance. Sosius was permitted to celebrate a triumph in Rome in 34 BC for his victory over Judea.

King of Judea

In 37 BC, Herod had won the throne, but only by force and only with the help of his foreign patrons, especially Antony. Unfortunately for Herod, Antony would soon lose a bloody power struggle with Octavian – a civil war, in fact. The contest was decided at the Battle of Actium, a naval battle off the west coast of Greece in 31 BC. Fortunately, Herod wasn’t there. Cleopatra had sent him to fight the Nabatean Arabs, which provided a useful alibi when, in 30 BCE, Herod excused himself to the victorious Octavian. Alternating between groveling and priding himself on his value as a potential friend, Herod won Octavian’s approval and kept his throne. Octavian was a realist and knew that Herod was the best man to keep Judea loyal to Rome. Shortly afterward, Antony and Cleopatra each took their own lives. Octavian was now the most powerful man in the Roman Empire. He was, in effect, Rome’s first emperor, and became known as Augustus. Herod proved to be one of his most loyal supporters and was duly rewarded.

Rome gave Herod back most of the land that had been taken from Judea by Pompey. The result was a big kingdom with a complex ethnic mix. This is not surprising, because ancient states were rarely ethnically homogeneous. Judea consisted of Jews, Greeks, and Samaritans. Two Arab peoples also lived in Herod’s Judea, Nabateans in the south and Itureans in the north.

There was little love lost among the various peoples under Herod’s rule, especially between Greeks and Jews. Friction often prevailed between Jews and Samaritans, although the Samaritans loved the Romans no more than the Jews did. Like the Jews, the Samaritans accepted the Torah, but denied the supremacy of Jerusalem and had their own Temple. Animosities forced Herod into a balancing act that was bound to make him unpopular with some. Most of his Jewish subjects hated Herod and never accepted him as a legitimate king. He was a commoner and an Idumean and was so loyal to Rome that he sent two of his sons there to be educated, eschewing a Jewish education in Jerusalem.

For the ruler of a small kingdom, Herod had a large army, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 men. He needed it, both to suppress opposition at home and to prove his worth to Rome abroad. Most of Herod’s soldiers were infantry, but there were some cavalrymen as well. Herod was first and foremost a military leader. The army’s job was to hold his kingdom together, deter internal resistance, and offer the Romans a strong and reliable ally. Most of his troops were Jews, many of them Idumeans. The army also included Greeks and Syrians, as well as Nabatean mercenaries. His bodyguard consisted of foreign mercenaries: Celts, Germans, and Thracians. Some of Herod’s commanders were Romans or at least Italians. They surely enabled certain Roman features in Herod’s army such as Roman-style marching camps and siegecraft. Herod built a series of fortresses around the kingdom, including in Jerusalem. Their purpose, to paraphrase a Greek assessment of Macedonian garrisons in central and southern Greece, was to serve as “the shackles of Judea”.

The Builder

No king of Israel had ever built on a grander scale than Herod. He reshaped the architecture and economy of his country from top to bottom, and proved to be a major funder of construction projects abroad as well. Building takes money, and Herod was rich. His wealth came from landholdings, taxes, profits on natural resources, and corruption.

Herod’s construction projects fit under three rubrics: Roman, Greek, and Jewish. Roman, first. In part to show that he was a faithful ally, in part for his own glory, Herod rebuilt much of his own kingdom in the Roman manner. He focused his Romanizing projects outside the majority-Jewish parts of his realm.

Rome was eager to spread the cult of Augustus around the empire. Worshipping the emperor as a god offended Jews, but pagan elites embraced it as a way of winning the empire’s favor. In the East, those elites had to get in line behind Herod.

Herod built three temples to Augustus. In the hill country north of Jerusalem, he rebuilt the ancient city of Samaria as Sebaste – Greek for Augusta. A Temple of Augustus dominated the site from a hilltop. Farther north, in the foothills of Mount Hermon, close to the current Israeli-Lebanon border, Herod built another Temple of Augustus in what Josephus calls beautiful white marble. It stood on the ancient road to Damascus, which in turn led to Mesopotamia. Jewish pilgrims to Jerusalem, coming from Parthian lands, would have passed by this shrine to Augustus.

Herod’s third Augustus temple stood on the central coast, where he turned a small Phoenician trading post into a major port. Caesarea Maritima, or Caesarea-by-the-Sea, rivaled the harbors of Athens and Alexandria as a trading center of the Eastern Mediterranean. The earlier Phoenician city lacked a good harbor; in fact, there were no harbors facing favorable winds on the kingdom’s coast. Herod solved the problem by having his engineers sink a mixture of cement and stones to build breakwaters around an enormous double harbor. Nearby, the Temple of Augustus overlooked the town from a high podium. On the coast south of Caesarea, near Gaza, Herod renamed a city after Augustus’s closest adviser, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa.

Herod also endowed temples, dockyards, gymnasia, theaters, baths, fountains, and colonnades all over the Greek-speaking cities of the Eastern Mediterranean. He gave funding to the financially strapped Olympic Games in Greece. His contribution was big enough to have Herod elected permanent president of the Olympics, an honor that he was able to enjoy in person when he attended the games in 12 BC.

Building pagan temples in the Holy Land offended pious Jewish opinion, but Herod also defended Jewish rights. In fact, he emerged as a champion of Jews in the Diaspora. He intervened with Augustus, for instance, to protect the rights of Jews in Asia Minor.

Herod’s most notable building project was reconstructing the central shrine of the Jewish people, the Temple. He began the undertaking around 19 BC. Josephus says that the king thought that the structure would make his name live forever.

The prior sanctuary, over which the new Temple was built, was showing the signs of age. It was old, small, and humble. Herod wanted to replace it with a structure that was nothing less than magnificent. The Talmud says that “One who has not seen Herod’s building has never seen a beautiful building in his life”. Herod was careful to put the building process in the hands of the priests. Although the Talmud considers Herod to have been generally wicked, it approves of his rebuilding the Temple.

Herod did not forget to honor his Roman patrons even in this most Jewish of sites. He had Agrippa’s name engraved on the Temple gate. Herod couldn’t build a shrine to Augustus on the Temple Mount, but he came up with an ingenious alternative: daily sacrifices at the Temple on behalf of the emperor. Augustus showed his approval by funding them out of his own purse.

Herod made Judea an integral part of the Roman Empire. Josephus claims that Augustus considered Herod second in importance only to his loyal general Agrippa, and Agrippa considered Herod second only to Augustus. As one historian puts it, “The kingdom of Herod in Judea was a jewel in the crown of Augustus’ Roman revolution.”

Herod is often called Herod the Great, and not without reason, but it is not known if he was called the Great in his lifetime, as some other ancient kings and statesmen were. Herod made himself indispensable. He convinced Rome that he was the only man who could maintain peace in a strategic area. Judea was the hinge between the two golden doors of the Roman East, the two provinces of Syria and Egypt. Herod was the guardian of the eastern marches, Rome’s local ally who could help the legions keep the Parthians out and the empire safe. And Rome did not discount the Parthian threat, even after a peace agreement in 20 BC, which Herod helped to negotiate. The northern cities of Roman Syria lay close to the Euphrates River border, within easy striking distance of Parthia’s armies.

Herod’s countrymen cheered his death. He had struck an uneasy balance and it started to fall apart as soon as he was gone. Herod wanted the Jews to be good Romans. Providence had other plans in mind. Far from being Rome’s best friend, Judea would become the empire’s most rebellious province.

Bestselling author Barry Strauss is a Classicist, military and naval historian, and consultant. He is the Corliss Page Dean Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University, as well as Bryce and Edith M. Bowmar Professor in Humanistic Studies Emeritus at Cornell University. His latest book, Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World’s Mightiest Empire, will be be available from Simon & Schuster in August 2025. Antigone has also hosted a discussion with Professor Strauss about Actium, the shaping of the Roman Empire, the place of ancient history in the modern world.