Fletcher Erskine

In compiling his monumental Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), Edward Gibbon faced a problem shared by Roman historians both long before him and still after him. In a moment of admirable transparency, Gibbon addresses the dilemma (1.10.1):

The confusion of the times, and the scarcity of authentic memorials, oppose equal difficulties to the historian, who attempts to preserve a clear and unbroken thread of narration. Surrounded with imperfect fragments, always concise, often obscure, and sometimes contradictory, he is reduced to collect, to compare, and to conjecture: and though he ought never to place his conjectures in the rank of facts, yet the knowledge of human nature, and of the sure operation of its fierce and unrestrained passions, might, on some occasions, supply the want of historical materials.

Gibbon is referring to a specific moment in what is now commonly referred to as the Crisis of the 3rd Century, a period of about 50 years (235–84) which saw approximately 70 individuals claim the imperial purple. Even the more successful of them rarely enjoyed reigns exceeding six years, and a mere handful died of certainly natural causes.

The worst years of the Crisis saw territorial fragmentation in East and West alike under secessionist usurpers. ‘Barbarian’ groups began pouring out of the north to ravage Roman civilisation. Decius (r.249–51) became the first emperor to die in battle with a foreign power, having set out to smite the barbarians on their approach.

His major successor, Valerian (r.253–60), was the first to be captured alive by a foreign power, having been taken by Shahanshah Shapur I during a failed Persian expedition and either flayed alive or kept in prison indefinitely. A twenty-year plague decimated countless throughout the Mediterranean. There was a sharp and marked devaluation of currency.

In short, it is safe to say the Empire was on the verge of collapse, a ‘little dark age’ before the fatal complications of the 5th century. But even outwith the complexities of understanding a period marked by a nearly gladiatorial contest for emperorship – so convoluted it is difficult in places to separate fact from fiction – there is a further problem, as noted by Gibbon: contemporary sources for this period are at best obscure – at worst, they simply do not exist.

The Crisis of the 3rd Century is ‘bookended’ by major sources. The history of Cassius Dio reaches 235, and the history of Herodian 238. Both sources just barely dip into the beginning of the Crisis. But even Cassius Dio’s witness to its beginning only comes to us from an epitome by the 11th-century Byzantine monk, Xiliphinus. Certain specificities may, therefore, be missing.

On the other end, we have the compilation of Panegyrici Latini, which, though elaborate and exaggerated propagandistic speeches, make useful references to recent 3rd-century events, the first after Pliny’s panegyric to Trajan being an anonymous address to the Western emperor Maximian in 289.

Beyond this, the Crisis period is something of a historiographical black hole. The closest we can get to a contemporary history is through Dexippus, an Athenian magistrate who seems to have died in the reign of Claudius II (r.268–70) and who committed much of his times to written memory. Unfortunately for us, only paltry fragments of his histories exist; and our only witnesses to him come from later sources or epitomised histories – most notably the Historia Augusta (written at some point in or after the late 4th century), which itself relishes almost laughingly in ironic, misleading, and even purely invented citations for its imperial ‘history’ covering emperors from Hadrian to Carinus (c. 117–284).

For the events of this time, then, we are almost exclusively reliant (as far as the earliest extant histories go) on the aforementioned Historia Augusta – with its obvious problems – and the Historia Abbreviata and Libellus Breuiatus of Sextus Aurelius Victor – which are, in fact, later epitomes of a lost, full-length archetype.[1] Moreover, these sources are a hundred years or more removed from the events of the Crisis. This, of course, does not exclude their reliability, seeing as Aurelius Victor certainly had access to Dexippus’ history (and, thereby, so did the Historia Augusta). But later sources can be clouded by their own contemporary concerns and source problems of their own, often making it difficult to distinguish historical fact from moralistic elaboration and fictionalisation.

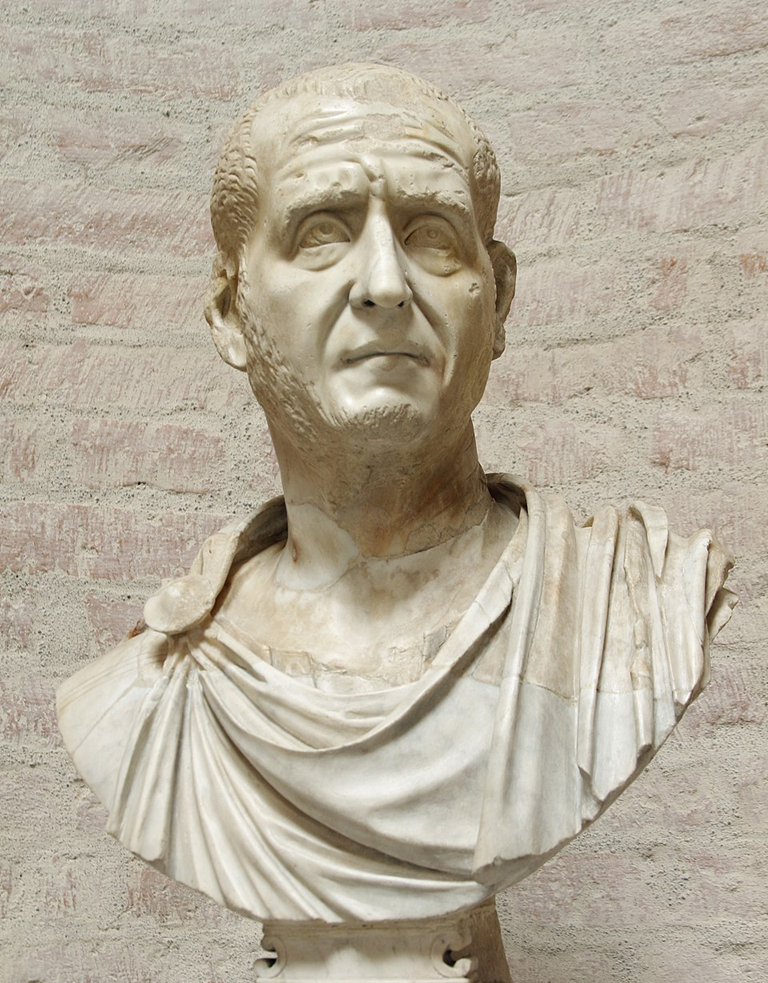

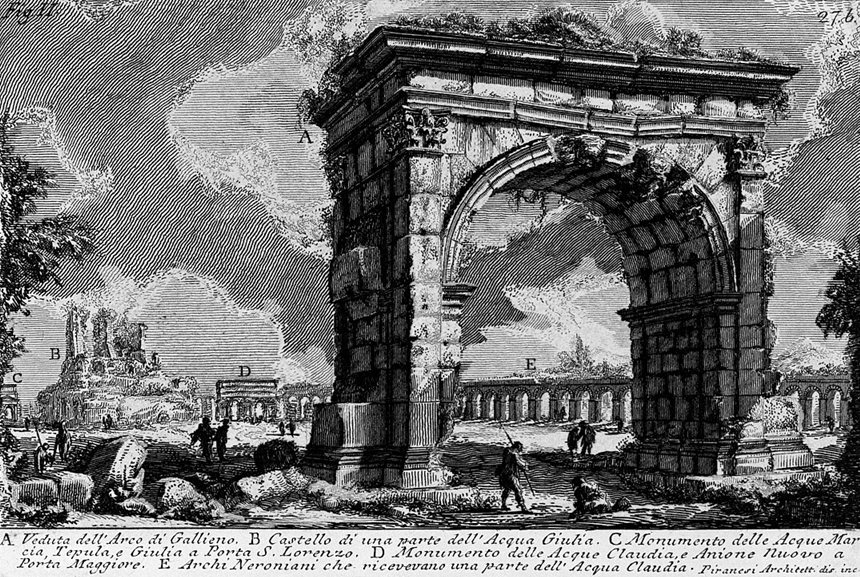

Our understanding of the reign of Gallienus (r.253–68) is a pertinent example. After becoming sole emperor following the capture of his father, Valerian, the imperial crisis reached its very nadir, with usurpers gaining control of most of the Western provinces and the Kingdom of Palmyra continuing to consolidate more and more of an autonomous empire out of the far Eastern provinces on the border with Persia.

At the same time, barbarians and other usurpers squabbled over Greece and the Balkans. Even Italy itself was not untouched by barbarian invasion. The picture we are left with of Gallienus, from Aurelius Victor, is one of a hedonistic figurehead “administering games and festal triumphs in order to consolidate more publicly his fantasies [sc. of stability]” ludos ac festa triumphorum, quo promptius simulata confirmarentur, exercens, Historia Abbreviata 33.15).

The Historia Augusta clearly elaborates on this characterisation, making Gallienus out to be a womanizer and lover of wealth who is envious both of usurpers and of his own successful commanders, like the future Claudius II, who make every effort to keep the Empire together. A disturbing anecdote, probably fabricated, has Gallienus personally ordering the slaughter of all males in Moesia – regardless of age – following the death of the usurper Ingenuus (Triginta Tyranni 11.5–9).

Panegyric 8.5, however, delivered around the year 297 to Constantine’s father, Constantius, has a far more moderate view of Gallienus’ reign, saying:

minus indignum fuerat sub principe Gallieno quamvis triste harum provinciarum a Romana luce discidium. tunc etiam incuria rerum sive quadam inclinatione fatorum omnibus fere membris erat truncata res publica…

The separation of these provinces from Roman enlightenment, though sad, had been less shameful during the reign of Gallienus: for at that time the Empire had been savagely dismembered almost entirely, whether by negligence or some movement of Fate…

The blame is still laid at Gallienus’ feet, however obscurely; but there is markedly not such a pejorative treatment of him as found in later histories. And this seems to accord with more recent archaeological and historiographical studies, which argue Gallienus was not only blackened by propaganda but actually a fairly effective emperor given the problems plaguing the Empire at the time.[2]

In short, even the witnesses we have to the history of the Crisis are complex and demand nuanced and careful investigation. Ultimately, the pressing questions in studies of the Crisis of the 3rd Century boil down to this: what was the Crisis really like, and what did the Romans of the time really make of it?

We have seen already that complications of historiography make these questions difficult to answer with certainty. But the 3rd century is also rather a barren field for examples of other classical literary genres. Whilst generals perpetually scrambled for the purple, it seems, on the surface, that the arts had little to say.

In reality, however, it may be that a political and historiographical focus on the 3rd century and its Crisis has suffocated other important voices. This is not to say this focus is unworthy; but a better understanding of the period as a whole may be found in sources which are ultimately (or seemingly) distant from the larger-than-life, bloody power-play of imperial politics in this era.

In her 2019 masterpiece, The Aesthetics of Hope in Late Greek Imperial Literature: Methodius of Olympus’ Symposium and the Crisis of the Third Century, Dawn LaValle Norman confronts the “dismissive” nature of 3rd-century scholarship, noting that literary scholars have been too quick to give credence to a narrative that “the third century proved to be the worst period in the long history of Rome”, and that “neither in Greek nor in Latin was there literary composition of artistic merit.”[3]

Norman attributes this perspective to a scholarly neglect of Christian literature of the 3rd century in particular; but she notes that even theologians and historians of Christianity have viewed this time as lacklustre and of little interest (excepting Origen). Through a lengthy study of the Symposium of Methodius of Olympus, a Christian bishop writing in Greek towards the end of the 3rd century, Norman attempts to bridge needless disciplinary gaps whilst simultaneously showing that literature in this period itself seems to cross generic boundaries, pointing to a crisis – and therefore reorientation – of artistry, style, and philosophy, one which ultimately paves the way for what we consider Late Antiquity.

After all, Methodius’ Symposium, as the name suggests, takes after the famous Symposium of Plato; but the dialogue is entirely composed of women who discuss the nature of chastity and pure love, the work ending in an alphabetical wedding-poem in praise of Christ, the mystical bridegroom of the mystical bride – the Christian Church – of which these women are together emblematic. It is exceptional as a confluence of Christian theology, Platonic philosophy, and Greek poetry and challenges the idea that the 3rd century represented a faltering of the arts.

But Methodius does not stand alone as the only example of a new literature in this hitherto reckoned ‘dark age’; nor is literature of the 3rd century limited exclusively to philosophy and theology. The North African Latin poet Nemesianus (fl. 280s) resurrected the Vergilian cursus (in part), writing four bucolic poems and a fragmentary Cynegetica, a poetic hunting manual.

Unlike Methodius, Nemesianus was clearly involved to some degree in imperial politics towards the end of the Crisis. He addresses Numerian and Carinus (r.283–4/5) directly and promises (what would presumably be) an epic about their respective Persian and Northern expeditions in the proem to his Cynegetica. The Historia Augusta even claims that Nemesianus competed with the future emperor Numerian in verse composition (Carus, Carinus et Numerianus, 11.2). He might well have been a court-sponsored poet.

We are able to date Nemesianus to 283 given specific references he makes in his Cynegetica. But, owing to his Vergilian flair, it is possible he wrote his eclogues at some point before the Cynegetica (as parallel to the Georgics), which would mean that Nemesianus was at the very least born during some of the worst years of the Crisis. He may even have witnessed some of its events with his own eyes – though this is sheer conjecture.

What is most significant is the bare fact of Nemesianus’ choice at this time in history to write bucolic, the Vergilian genre par excellence in the Latin literary tradition. Indeed, his first Eclogue involves the characters Tityrus and Meliboeus, the self-same characters of Vergil’s first Eclogue. But Meliboeus is recently dead in the narrative, and Tityrus is songless, emphasising to his young companion Thymoetas that his time is past. It takes this youth Thymoetas singing a eulogy for Meliboeus to reinvigorate the seemingly depressed and elderly Tityrus, who begs, towards the end of the poem, “Keep going, lad! Don’t stop the song you’ve begun!” (perge, puer, coeptumque tibi ne desere carmen, 1.81).

Because the Latin bucolic genre is so programmatic and driven by recognisable characters, Nemesianus’ poetic project is clearly intentional. The inability of Tityrus to perform a song is at variance with what we would expect from the genre and suggests, allegorically, that Nemesianus – through the character of Thymoetas – is resurrecting the very archetype of Classical Latin poetry in response to its perceived decline.

That Nemesianus’ Meliboeus is described throughout Thymoetas’ eulogy with regnal and governmental attributes furthermore implies the loss of a societal – even imperial – golden age, necessarily replaced by difficulties which could be nothing other than the crises that afflicted the 3rd century. These themes diffuse a sombreness into Nemesianus’ poetry, and scholars such as Evangelos Karakasis (Song Exchange in Roman Pastoral (De Gruyter, Berlin & New York, 2011).)) have noted that Nemesianus represents a decisive shift into a more elegiac poetry which afterwards characterises Late Antiquity.

Much more work on Nemesianus is waiting to be done. At the very least, it is clear that his literary works, like that of Methodius, reinvent genre and display a newness of forms, themes, and style. Nor are they the only such examples of literature. Plotinus, Porphyry, and Longinus were all active philosophers in the Crisis period and made important contributions that had lasting effects. An anonymous elegiac poem, De ave phoenice, may have been written by Lactantius, the famous Christian theologian and historian. Quintus Smyrnaeus’ Posthomerica, an epic on the aftermath of the Iliad, can also be dated to the 3rd century. The list goes on.[4]

As LaValle Norman (2019, 23) rightly notes,

dividing writers into intellectual genealogies has often blinded scholars to the reality that many third-century writers wrote across modern disciplinary divisions…

If we attempt to confine ancient literature to artificial boundaries and typical epochs, the 3rd century will prove a meagre harvest indeed for the scholar. But if we, as LaValle Norman suggests, view the literature of that century as fundamentally transitional, shaped by experimentation, reinvention, and cross-pollination in tandem with societal changes and political turmoil, we find ourselves gazing into the very furnace in which Late Antiquity was smelted.

Though there has been a perennial interest in the imperial literature of the first two centuries AD, late-antique literature itself has received long-overdue attention and good-faith scholarship in the last 50 years, and the momentum of this work continually grows. What is still less appreciated, however, is the century which gave birth to it, too often relegated solely to historiographical, archaeological, and military studies.

With a holistic perspective that includes interpreting the literature of this time on its own terms and in its own context, it will be possible to paint a much clearer – and more colourful – picture of this most enigmatic period of Roman history, a ‘little dark age’ which, despite its troubles, had flickers of the light of learning, art, and culture beneath its cloudy surface.

Fletcher Erskine is an alumnus of the University of Glasgow (MA Hons., Greek/Latin). After studying at the University of Cambridge (MPhil, Classics), he worked on the ‘Last Historians of Rome’ project as a research assistant at the University of Edinburgh and will be starting a PhD project there on a topic in Late-Antique Latin Bucolic in the autumn of 2025.

Further Reading

It is worth emphasising here how much of an influence Dawn LaValle Norman’s The Aesthetics of Hope in Late Greek Imperial Literature: Methodius of Olympus’ Symposium and the Crisis of the Third Century (Cambridge UP, 2019) has had on me – not only in my own studies but also in writing this piece. Much significant scholarship on 3rd-century literature is cited within and proves indispensable for understanding better the state of such studies. For those with institutional access, it can be read here.

The interpretation of Nemesianus in this piece is based on a recently published article of my own in Classical Quarterly, which delves further into Nemesianus’ first Eclogue and its relationship with the Crisis of the 3rd Century. It is available to read via Open Access here.

Apart from the different works and texts cited throughout this article, David Potter’s The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395 (Routledge, London, 2014) is a must-read for a detailed overview of the 3rd century and its crisis of emperorship. A three-volume Loeb edition of the Historia Augusta, revised by David Rohrbacher, was published in 2022 and provides an enthralling and accessible account of the Crisis period in volumes 2 and 3.

The ‘Last Historians of Rome’ project, currently underway between the Universities of Edinburgh and Nottingham, will result in new, authoritative, and state-of-the-art editions and translations of (inter alios) both Aurelius Victor and the Historia Augusta. Their website provides links to further reading on and useful editions of late-antique histories.

Notes

| ⇧1 | See further J. Stover and G. Woudhuysen, The Lost History of Sextus Aurelius Victor (Edinburgh UP, 2023), and this Antigone article. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | See, e.g., I. Syvänne, The Reign of Emperor Gallienus: the Apogee of Roman Cavalry (Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2019). |

| ⇧3 | D. LaValle Norman, The Aesthetics of Hope in Late Greek Imperial Literature: Methodius of Olympus’ Symposium and the Crisis of the Third Century (Cambridge UP, 2019) 25, citing G. Kennedy, A New History of Classical Rhetoric (Princeton UP, 1994) 242. |

| ⇧4 | For a useful ‘map’ of 3rd-century literature, see LaValle Norman (as n.3) 22–68. |