Matthew Gluckman

A man flees a prophecy – and still dies. A farmer digs for water and finds gold. An eagle drops a tortoise on a fleeing poet. A wrong turn delivers an assassin to his target. Chance – or destiny – seems to script every twist. Yet every gambler knows the truth: the house sets the rules, the odds, even if the cards look random. When we ask whether history’s improbable moments are mere accidents or parts of a larger design, we confront a dilemma as old as philosophy itself.

The Romans named these forces fortuna (fortune) and fatum (fate), while providentia (providence) signified a divine intellect ordering events. Casus (chance) described those unexpected convergences of causes that escape our control. Behind it all stands human libertas – freedom, the capacity to choose. Boethius and Cicero both reject pure randomness and unyielding fatalism, but they draw the line between freedom and necessity in very different places.

Boethius and Cicero each stake out a nuanced middle ground between fatalism and randomness by situating human freedom within a larger causal framework – yet they differ on how that framework operates. Boethius grounds all casus in a comprehensive divine providentia, an eternal intellect that orders every accidental convergence without negating our libertas; providence supplies the logical structure within which unpredictable outcomes still unfold. Cicero instead locates casus at the intersection of fortuna and natura (nature), insisting that our libertas operates through natural causes and moral decisions without recourse to a binding fatum or transcendent planner. In juxtaposing providential order against human freedom, these philosophers show how “the house” of the universe both constrains and enables choice – ensuring that chance remains real but never arbitrary, and that freedom remains possible yet always contextualized.

In Latin, fortuna (fortune) and fatum (fate) address two seemingly different aspects of destiny. Casus (chance) describes events that appear accidental, while providentia (divine providence) speaks to a rational order behind all occurrences. Both thinkers, influenced significantly by Aristotle’s Physics Book 2,[1] understand ‘chance’ as arising from multiple converging causes. This notion laid the groundwork for Boethius’ later assertion that apparent chance is merely the intersection of causes that are part of a larger divine order.[2] In parallel, debates between Stoics and Epicureans further enriched this discourse. The Stoics emphasized a deterministic universe governed by fate (fatum), whereas the Epicureans defended the notion of randomness (casus) to preserve human freedom.

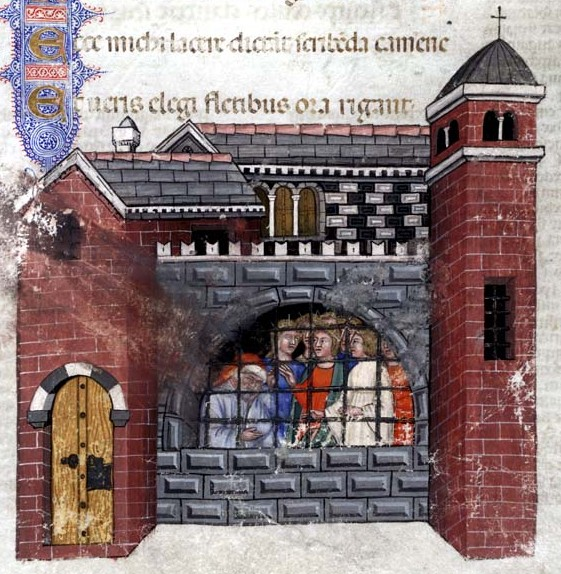

Boethius’ magnum opus, The Consolation of Philosophy, was composed around AD 523 while he languished in prison, charged with treason by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great. Structured as an alternating prose‑and‑verse dialogue between the fallen Roman statesman and the personified Lady Philosophy, the treatise begins with his lament over fickle fortuna and swiftly expands into a probing inquiry into whether life’s seemingly random reversals are woven into a divinely ordered plan. Instead, he argues that every event, no matter how unforeseen, is part of a universe guided by a divine plan.

In Book 5, Prose 1, Boethius poses the crucial question: Quaero enim an esse aliquid omnino et quidnam esse casum arbitrere (“For I ask whether you think there is anything at all that is chance, and if so, what it is,” 5.1.3). Lady Philosophy’s response disavows uncaused events: Si quidem… aliquis eventum temerario motu nullaque causarum conexione productum casum esse definiat, nihil omnino casum esse confirmo et praeter subiectae rei significationem inanem prorsus vocem esse decerno (“If indeed someone were to define chance as an event brought about by a reckless motion without any connection of causes, then I affirm that chance does not exist at all, and apart from being a mere name signifying a subject, it is an utterly empty word, I declare,” 5.1.8 ).

The phrase temerario motu (“reckless motion”) evokes Aristotle’s critique of randomness as purposeless. By coupling it with nullaque causarum conexione – “without any connection of causes” – Boethius emphasizes that genuine chance, understood as uncaused spontaneity, is an incoherent concept. The term inanem, here translated as “empty,” is equally significant: chance, when stripped of causal connections, is not merely rare but semantically hollow. It names nothing real.

Yet Boethius does not deny that events can surprise us. He refines the definition of casus as inopinatum ex confluentibus causis in his quae ob aliquid geruntur eventum (“an unexpected event arising from the convergence of causes in things that are done for a purpose,” 5.1.18). The adjective inopinatum – “unforeseen” – captures the human perspective of surprise. Confluentibus causis – “converging causes” – reveals that chance is not a root cause but a junction where independent causal strands intersect. The prepositional phrase ob aliquid geruntur – “done for a purpose” – reminds us that these strands originate in intentional actions, whether by humans, nature, or Providence.

Central to Boethius’ resolution is the concept of providentia. He asserts that ordo ille inevitabili conexione procedens qui de providentiae fonte descendens cuncta suis locis temporibusque disponit (“That order, proceeding by an inevitable connection, which – descending from the source of Providence – arranges all things in their own places and at their appointed times,” 5.1.19). Here providentiae fonte (“source of Providence”) is the divine intellect from which the cosmos flows. The adjective inevitabili connotes necessity, not in the sense of coercion, but as the logical coherence binding cause and effect. Providence, then, is neither capricious nor absent; it is the silent architect behind every causal nexus.

This seamless order might seem to threaten human freedom. Boethius anticipates the objection in Book 5, Prose 2: Sed in hac haerentium sibi serie causarum estne ulla nostri arbitrii libertas an ipsos quoque humanorum motus animorum fatalis catena constringit? (“But in this series of causes that are bound together, is there any freedom of our will? Or does the chain of fate also bind the movements of human souls?” 5.2.2). Lady Philosophy replies with clarity: Est, neque enim fuerit ulla rationalis natura quin eidem libertas adsit arbitrii (“There is freedom; for no rational nature could exist without possessing freedom of will,” 5.2.3).

The noun libertas here is paramount. It is not an abstract concession but a defining attribute of rationalis natura. By stating that no rational nature could exist without libertas, Boethius places freedom at the core of personhood. The verb adsit (“be present”) highlights that liberty is an inseparable companion to reason. Boethius then distinguishes degrees of freedom. Divine beings possess perspicax iudicium (“keen judgment,” 5.1.7), incorrupta voluntas (“unspoiled will,” 5.1.7), and efficax optatorum potestas (“effective power to attain desires,” 5.1.7). Human souls, when in mentis divinae speculatione (“in contemplation of the divine mind,” 5.1.8), enjoy a fuller liberty, but when dilabuntur ad corpora (“slip into bodily existence,” 5.1.8), their freedom wanes. At the nadir, souls in vitiis deditae rationis (“given over to vices,” 5.1.9) become captivae (“captives”) of their own misjudgments. Through this gradation, Boethius reconciles an all-encompassing Providence with genuine moral responsibility: the divine plan provides the framework, but each soul’s orientation toward truth or vice determines its measure of freedom.

Cicero, writing over half a millennium earlier, confronts similar puzzles in De Fato, engaging with both the determinist Stoics and the indeterminist Epicureans. He rejects the Stoic insistence on fate (fatum) as an omnipotent force. In chapters 6–7 he issues a decisive challenge: Si fati omnino nullum nomen, nulla natura, nulla vis esset et forte temere casu aut pleraque fierent aut omnia, num aliter, ac nunc eveniunt, evenirent? (“If fate had no name, no nature, no power whatsoever, and if most or all things happened purely by chance, would events occur any differently than they do now?”)[3]

The triad nomen, natura, vis – “name, nature, power” – serves as a rhetorical device to strip fatum of its substance. If a concept lacks identity (nomen), essence (natura), and efficacy (vis), it is an empty category. Cicero’s inclusion of forte temere casu (“by chance, at random”) foregrounds the Epicurean claim that indeterminacy undergirds free will. Yet Cicero shows that even without invoking fate, fortuna and natura can explain the sequence of events.

He concedes that some phenomena stem from naturae contagio (“the influence of nature”), as in the simultaneous illness of brothers or the development of fingernails – cases where he admits naturae contagio valet, quam ego non tollo (“the influence of nature holds some sway, which I do not deny” ). However, he draws a firm line at universal fatalism: in aliis autem fortuita quaedam esse possunt, sunt quidem absurda (“in other cases, certain events may indeed be fortuitous, which are indeed absurd [if attributed to fate]”). By labelling Stoic examples absurda, Cicero highlights that attributing every occurrence to fate renders the concept ludicrous.

In his critique of the Stoic polymath Posidonius of Rhodes – whose historical compendium paraded anecdotal “proofs” that fate governs every detail – Cicero slows down to test the logic of each story. One favourite Stoic exhibit concerns the poet Daphitas, for whom an oracle foretold death by a horse. Posidonius triumphantly reports that the prophecy was fulfilled when Daphitas was executed.

Cicero picks the tale apart point‑by‑point: Did the oracle mean a literal animal, a carved cavalry emblem, or any locality with an equine name? What of the magistrate who chose the execution site, or the chronicler who preserved the story? By tracing these ordinary causal links – human decisions, geography, homonymy – he demonstrates that the outcome could have unfolded without any guiding fatum. Cicero’s emphasis on fortuita – incidental factors that piggy‑back on regular chains of cause – shows that impressive coincidences do not justify sweeping metaphysical conclusions.

Cicero’s argument has moral urgency. He warns that if fate is universal, human effort becomes pointless: virtue loses its reward and vice its penalty. This so‑called “Lazy Argument” – a classical objection insisting that determinism discourages action – runs through De fato: if every outcome is fixed in advance, why deliberate, labour, or pursue justice? By preserving a role for casus and fortuna, Cicero defends the practical value of choice. The universe need not be a sealed clockwork; it can instead be a living arena where unexpected events spur human action and prompt us to rethink how fate, chance, and deliberate choice interact across history. An illustration of this complexity is found in the tale of Aeschylus’ death by tortoise, which exemplifies this tension between apparent randomness and hidden design. According to Pliny, the tragedian fled indoors to avoid a prophecy that he would die by a falling object – only to be struck down by a tortoise dropped by an eagle.[4] On the surface, this is inopinatum in the fullest sense: an “unforeseen” convergence of causes that startles our rational expectations.

Yet Boethius would insist that no event occurs nullaque causarum conexione (“without any connection of causes”) and that what we call chance is merely inanem when severed from its causal roots. The eagle’s hunting instinct, the tortoise’s shell, the rock’s shelter, and Aeschylus’ own flight coalesce in a pattern too intricate for pure accident. Cicero, ever attuned to empirical explanation, would label the anecdote absurda (“absurd”) when attributed to fate – while acknowledging that contagio naturae, the influence of natural forces, suffices to explain why the tortoise fell at that precise moment. In both accounts, the story resists a simplistic reading as either blind luck or inexorable decree.

Polycrates’ ring, cast into the sea to avert Fortune’s jealousy and then returned inside a fish, dramatizes the paradox of human effort against cosmic sway. Boethius hears in this episode the echo of ordo inevitabili conexione procedens – the “unbreakable order proceeding with inevitable connection” that descends from providentiae fonte. Even when someone tries to outwit Fortune, their action still ends up part of the divine plan. Cicero, however, would dissect the ring’s material properties, the fishermen’s habits, and the regional diet to show how fortuita quaedam – incidental, converging causes – can yield an outcome that feels fated yet requires no cosmic will. The ring’s reappearance is neither pure accident nor metaphysical necessity, but a demonstration that Providence and chance are two sides of the same coin.

In June 1914, Gavrilo Princip’s craving for a sandwich and a driver’s wrong turn conspired to place him before Archduke Franz Ferdinand – an event Aristotle would call casus in its purest form, “an unexpected event arising from the convergence of causes not aimed at that outcome.”[5] Boethius might frame this moment as one more spark in the cosmic design: inopinatum ex confluentibus causis, yet woven into a larger design that only Providence fully comprehends. Cicero, stripping fatum of nomen, natura, and vis, would highlight that driver error, Princip’s hunger, and the café’s location suffice to explain how a world war began – no binding fate necessary. The assassination illustrates that small, contingent actions can cascade into historical upheaval, highlighting the moral stakes of human choice within a framework of converging causes.

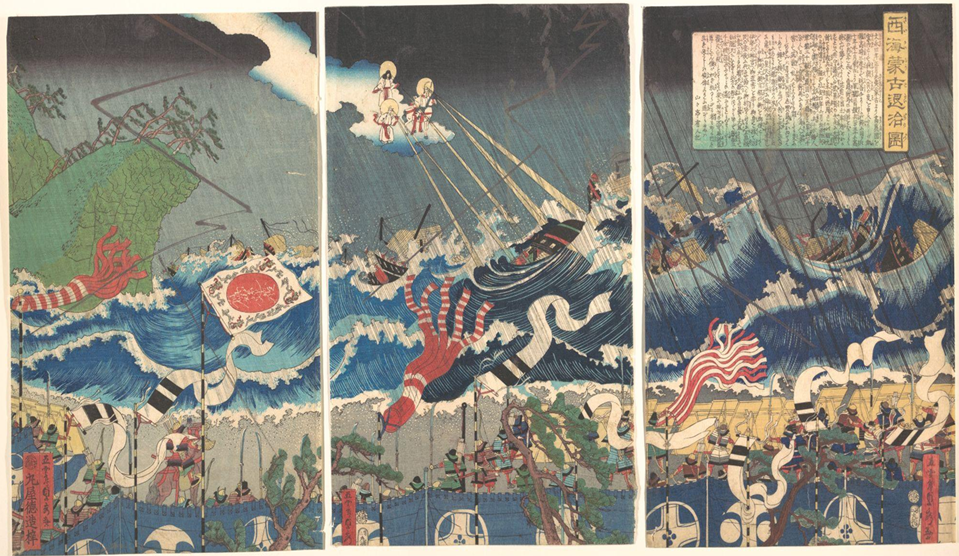

The Kamikaze Typhoon of 1281 offers a final picture of chance interpreted as providence. When Kublai Khan’s fleet lay vulnerable off the Japanese coast, a sudden storm – hailed as kamikaze, the “divine wind” – annihilated the invaders. Boethius would see in the typhoon’s precise timing the hand of providentia, orchestrating natural forces according to an ordo inevitabili conexione procedens that spans heaven and earth. Cicero, ever the naturalist, would point to barometric pressure, ocean currents, and seasonal monsoons – contagio naturae – as sufficient to explain why the wind shifted when it did. The storm thus becomes both a symbol of divine favor and a testament to the power of natural causation, reminding us that casus and providentia need not be opposed.

These stories reveal that Boethius and Cicero, though employing different vocabularies, converge on the conviction that neither pure randomness nor absolute determinism captures the fullness of human experience. Boethius’ reliance on providentia and his articulation of inopinatum ex confluentibus causis emphasize a cosmos in which every event, no matter how surprising, fits within a divine plan, yet never at the expense of genuine libertas. Cicero’s stripping of fatum to reveal the sufficiency of fortuna and contagio naturae preserves a universe where human effort and moral responsibility remain real. Their disagreement, when examined closely, is less about the substance of causation than about the level at which one locates ultimate explanation: the perspective of Providence or the temporal mechanics of nature and chance.

For human agency, this synthesis means that we are neither helpless marionettes nor omnipotent architects. We act within a web of converging causes – some visible, some hidden – but our capacity for libertas, intrinsic to our rationalis natura, endures. We deliberate, we choose, we face the consequences. The house may deal the cards, but how we play our hand still matters.

Boethius and Cicero guide us to a balanced vision of the universe – one in which casus is not an inanem concept, nor is fatum an all‑consuming force. Instead, we inhabit a world where providentia and fortuna, causation and chance, intertwine to shape the course of events. Modern advances in probability theory, chaos theory, and quantum mechanics echo these ancient insights: probability quantifies the likelihood of inopinatum events without denying causal order; chaos theory reveals how deterministic systems can yield unpredictable outcomes, resonating with Boethius’ confluentibus causis; and quantum indeterminacy reopens the debate on whether the cosmos allows genuine spontaneity or is scripted by a deeper necessity.

The metaphor of “the house always winning” aptly captures the tension between an overarching order – whether conceived as divine Providence or the capricious workings of Fortuna – and the genuine freedom of human agency. Just as a casino’s odds favor the dealer, the cosmic framework described by Boethius and Cicero sets the conditions under which events unfold, yet it does not render human choice illusory. Rather, every decision we make participates in the intricate convergence of causes that both thinkers elucidate: for Boethius, as nodes in an ordo descending inevitabili conexione from providentiae fonte; for Cicero, as the product of contagio naturae and fortuita quaedam that preserve moral responsibility. In this sense, while the house may indeed possess structural advantages, it is the player’s exercise of libertas – the capacity for reasoned deliberation and ethical action – that ultimately gives meaning to the game of life.

Matthew Gluckman is an incoming freshman at the University of Pennsylvania with a deep passion for Classical studies. At Hackley School, he co-led the Classics Club and founded the Hackley Classics Symposium, an event that united students from across the tristate area with professional Classicists to explore themes like the intersection of Latin literature and artificial intelligence. He has taught Latin to younger students through an outreach initiative and conducted an independent study on Lucretius, using ancient philosophy to inform modern scientific thinking.

Notes

| ⇧1 | In Physics 2.4–6, Aristotle distinguishes chance (τύχη, tychē) and spontaneity (αὐτόματον, automaton) from purposive natural action, defining them as coincidental outcomes of causal chains that lack a final cause (telos); such events are therefore “purposeless”. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | C.H. Lüthy, “Conceptual and historical reflections on chance (and related concepts),” in N.P. Landsman & E.J. van Wolde (edd.), The Challenge of Chance: A Multidisciplinary Approach from Science and the Humanities (Springer, Berlin, 2016) 9–47. |

| ⇧3 | All translations from R.W. Sharple’s edition of Cicero’s On Fate (Aris & Phillips, Warminster, 1991). |

| ⇧4 | Theodoros Karasavvas, “Eagle mistakes bald head for a rock: the bizarre circumstances surrounding the death of Aeschylus,” Ancient Origins, 1 Jan. 2018, available here. |

| ⇧5 | Mike Dash, “The origin of the tale that Gavrilo Princip was eating a sandwich when he assassinated Franz Ferdinand,” Smithsonian Magazine, 15 Sep. 2011, available here. |