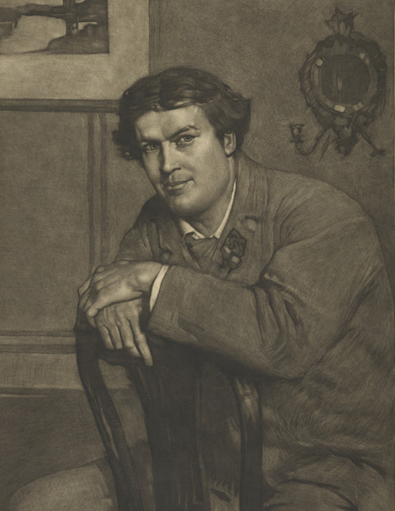

J.K. Stephen

We routinely publish interesting, and largely forgotten, essays about the Classics from previous centuries. These pieces are both interesting for their own arguments, and for what they reveal about how the study of the Greek and Roman worlds was viewed in the time and place of their composition.

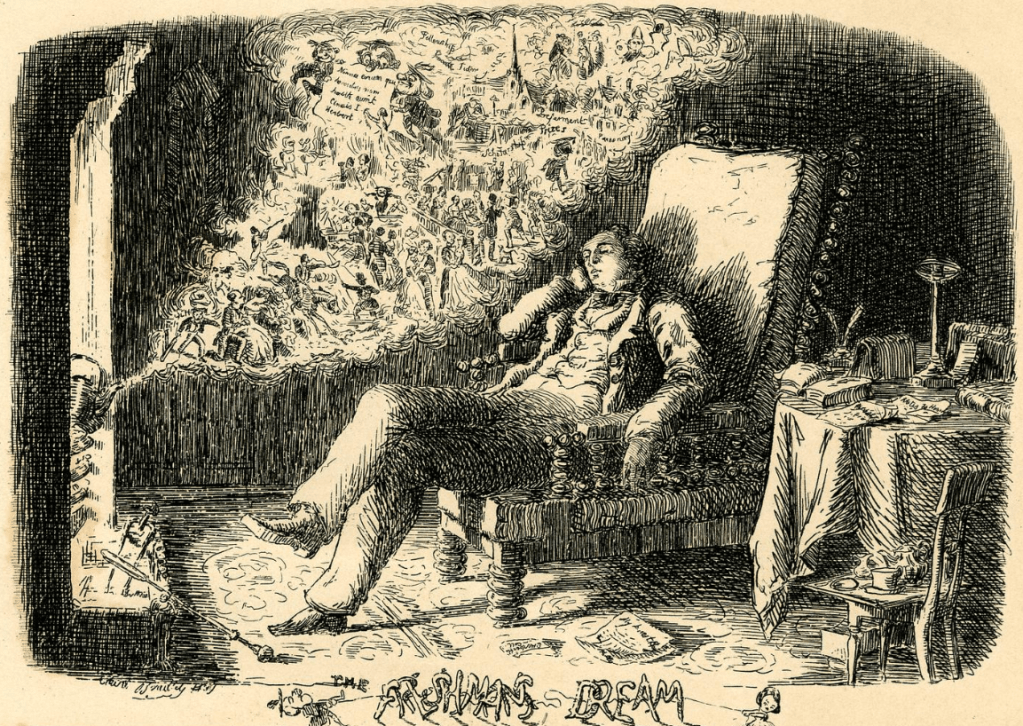

This piece is devoted to a simple question: should the University of Cambridge require all of its students to know some Ancient Greek? This was not an abstract proposition: for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Cambridge students had to sit, by their fifth term (i.e. two thirds through their second year of, typically, three years of study) a series of tests called the Previous Examination (often nicknamed “Little Go”). Introduced in 1824, it tested basic Greek, Latin, theology, and (soon enough) mathematics. If the test was not passed, you could not matriculate and go on to sit the special examinations for the B.A. degree you sought.

Six exams concerned Classics, largely involving translation into English. Alongside a paper on a prescribed Greek Gospel, and one testing the rudiments of Greek and Latin accidence and grammer, there were two papers requiring translation from a Greek prose author (often Plato and a historian), and from two Latin authors (often Cicero and Virgil). For this examination, there was no ‘composition’, i.e. translation into Greek or Latin. To gain a sense of the difficulty (or ease!) of these papers, you can peruse the Previous Examination for Michaelmas Term 1884 here.

The debates about removing the compulsory examination in Greek first began in 1870, and continued for half a century. The driving factors behind the movement to abolish compulsory Greek were: the rising importance of modern languages, especially French and German; the ever-increasing role of science in the rapidly-evolving world; the introduction of schools in 1870 that were not expected to teach Greek at all; the lack of “practical utility” of the “dead languages”; the fact that many non-Classicists who “crammed” their Greek at university did not enjoy it, soon forgot it, and were distracted from the studies they enjoyed. Among the more well-known figures who supported abolishing compulsory Greek were Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, Henry Sidgwick, T.H. Huxley, Sir George Trevelyan, Henry Montagu Butler and Arthur Balfour.

James Kenneth Stephen, often styled J.K.S., was a remarkable figure. Unfortunately, this is not the place to allow for detailed commentary on his short and tragic life. Born in 1859, and a second cousin to Virginia Woolf, he passed through Eton as a King’s Scholar — becoming a legendary figure in the Wall Game — before passing on to King’s College, Cambridge, where he read History. Stephen’s interests were wide ranging (he was variously an Apostle, President of the Union, and a keen thespian), although poetry was his chief love. After a spell devoted to the largely impossible task of educating the teenage Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and son of the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), Stephen became a Fellow of King’s in 1885. Despite the notionally academic position, his interests soon turned to London, where he studied at the Bar and took up journalism, launching a weekly called The Reflector in 1888. He became particularly celebrated as a public speaker.

A traumatic head injury sustained the following year, combined with a perhaps already present mental condition, led to the development of a bipolar disorder. In 1891 he returned to Cambridge to take private pupils in constitutional history. Despite his increasingly erratic behaviour, Stephen published two collections of poems (Lapsus Calami and Quo Musa Tendis?) that year. And, in November 1891, he weighed in on the Compulsory Greek question with his essay reproduced below: The Living Languages.

It was later in 1891 that Stephen had a complete mental breakdown and was committed to an asylum in Northampton. On hearing in January 1892 that Prince Albert Victor had died on pneumonia aged 28, Stephen went on a hunger strike and died three weeks later, aged 32.

Yet his eloquent and impassioned case for retaining compulsory Greek was part of a successful victory: the grace to appoint a syndicate to consider alternatives to Compulsory Greek was defeated. But victory was temporary: while in 1903 the report of a syndicate suggesting alternatives to Greek was rejected by the largest number of votes then ever cast at Cambridge (1,559 vs 1,052, 75% of whom were alumni who returned to the city to have their say), in 1913 another syndicate report suggesting alternatives was paused by the Great War (1914–18) but, after the dust fell and the smoke dissipated, compulsory Greek was easily abolished in 1919 (161 vs 15).[1]

Stephen closes his account with the premonition that the arguments against Greek could and would be deployed against compulsory Latin too. In 1960, both Compulsory Latin (then O-Level = GCSE standard) was abolished, along with the Previous Examination. (Oxford, in tandem, removed compulsory Greek in 1920 and Latin in 1960.) Stephen’s argument that if universities did not require Greek or Latin a sharp decline would follow in the teaching of Greek and Latin in schools was grimly true. No decision has contributed more to the mistaken belief that these languages are the special preserve of “the elite” who attend those schools that have chosen to preserve the teaching of these subjects. In 2025, neither Cambridge nor Oxford requires Classics students to know Greek or Latin before entry.

Three things are worth bearing in mind when reading the essay: the case is limited to the realities of Cambridge and Oxford in the 1890s (an intellectual space where men mostly had learned Latin through school, and many Greek, and women had only just been admitted to the University, but could not yet take degrees); the author acknowledges that the school system could be much better, but universities should be upstream not downstream from schools, setting appropriate expectations; the author writes as someone who felt his life incalculably enriched by access to Greek, even though it played no direct role in his life after leaving school.

The Living Languages

A Defence of the Compulsory Study of Greek at Cambridge

J.K. Stephen, M.A.

Late Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge

(Macmillan and Bowes, Cambridge, 1891)

CHAPTER I

I desire to state some of the reasons which have induced me to join the Committee for opposing the Grace to appoint a Syndicate in order to suggest an alternative to Greek as a compulsory subject in the Previous Examination. At the present time it is the rule that all candidates for a degree at Cambridge (with a trifling exception which it will not be necessary to refer) must pass an examination of an elementary nature in Latin and Greek as well as in certain other subjects. It is now proposed to appoint a syndicate for the purpose of seeing whether a substitute for Greek can be introduced. This proposal, notwithstanding its apparently tentative and preliminary nature, is strongly opposed by a large part of the University. It is obvious that the burden of proof falls to some extent upon those who are opposed to what may be described as a measure of “examination and enquiry”. But the circumstances of the case are, I think, such as to justify those who support the compulsory study of Greek in the attitude which they have taken up. The proposal to appoint a syndicate is not new. Such proposals have been made before. Such syndicates have been appointed. The syndicates have reported. The reports have been considered. The evidence on which the reports were based has been minutely stated and carefully examined. Proposals founded upon the reports have been formulated, brought forward, discussed and rejected. If there is a question on which the University has made known its opinions to the world at large, it is the question of compulsory Greek. The decision to retain the existing arrangement is not only a firm and distinct decision, but it is, as a study of the history of this question at Cambridge will show, an increasingly emphatic decision. The last formal vote on the subject gave to the supporters of Greek a more decisive majority than they had had before.

The opposition to the appointment of a syndicate would be reasonable and right, if it were based on no other grounds than that the question has been decided and ought not to be reopened. But it is based on other grounds. The determination of those who are opposed to Greek not to let the question sleep, and their repeated reappearance in the field after crushing defeats, are signs of, what is otherwise clearly enough demonstrated to observant members of our community, the fact that a deliberate and implacable hostility is entertained towards the old studies of the University by some of those who consider themselves the champions of the new. Fortunately, this hostility is very far from comprising all the teachers of science and advocates for the development of scientific studies in Cambridge. Many scientific teachers are as firmly convinced of the utility of compulsory Greek as the most ardent votaries of scholarship. And, unfortunately, the teachers and students of Greek are not unanimous on the other side. Many finished scholars, and popular lecturers, thinking that they perceive that the study of Greek and Latin can no longer hold its honoured place, beside the study of mathematics as the principal forms of academic energy, are not only willing, but anxious, that the compulsory study of Greek by all members of the University, fit or unfit, should be discontinued, and that their favourite study should, like Ethics, or Embryology, or Sanskrit, be confined to those who are fit to benefit by it to the full extent of its splendid possibilities, and likely to further the extension of the study into every corner which the zeal of philologists, and the acumen of archaeologists have hitherto left unexplored.

But, notwithstanding these exceptional cases on the one side and on the other, it is idle and useless to attempt concealment of the fact, that the contest now going on is part of a larger contest, which has long been waged, and is apt to crop up in every department of academic business, between the advocates of the old learning and of the new. In this dispute the teachers of science are no doubt the aggressors. Nobody tries to interfere with them: and they have never any difficulty in obtaining at least a very fair share of their not too moderate demands on the emoluments and resources of the University. It is needless to ask whether the adherence of the teachers of classics to the maxim of “live and let live” is due to constitutional tolerance, or to a sense of weakness, and a desire to keep what they have got, and let others take what they can. The fact remains. But if the teachers of Latin and Greek are tolerant, many of the teachers of science are aggressive. They not only wish to promote the study of their own subjects to a position as eminent as possible, but they desire to strip the older studies of a primacy which, in the opinion of their rivals, they ought never to have attained. Galled by the sense of undeserved inferiority in the academic hierarchy, they are desirous not only to build up for themselves a firm and enduring structure, but to pull down the edifice which testifies to the past greatness of their predecessors. If anyone chooses to deny the existence of this aggressive and hostile attitude on the part of a number of teachers and students of science, he will waste his labour. Nobody who knows anything of the facts will believe him. The most hearty sympathy with those who have made the scientific school in Cambridge what it is, and the most loyal desire that it may thrive and develop, cannot blind an honest man to the fact that science has put Latin and Greek on their defence, and will humiliate and cast them down if it can. It is the knowledge of this fact, to which reference is seldom made, and which a laudable courtesy prevents us from openly discussing without due reserve, which, along with unwillingness to reopen a closed question, has led the supporters of compulsory Greek to meet their opponents on the threshold, and to oppose an apparently harmless and purely preliminary proposal. The fact that this hostility to Latin and Greek actuates some of those in whose support I write in the attitude they have taken up, justifies me in departing from that reticence about it, which it might otherwise be seemly to observe.

It may appear at first sight that the question whether Greek should be a compulsory subject in the Previous Examination could not be exceedingly important: and that it ought to be determined solely by considerations connected with the convenience of competitors for the Previous Examination and their teachers. It might be urged, with something like plausibility, that if it could be shown that students of science are incommoded and delayed by the examination, and that good scholars neither gain nor lose by having to undergo a test which is far below the level of their capacities, the retention of Greek must be undesirable. But such a view, as all enlightened supporters of the proposed change would readily admit, leaves out of sight all the most important aspects of the question. The reason for making Greek compulsory for all those who wish to take a degree at Cambridge, is not that students of science should spend a few weeks “cramming” a subject which they will forget as soon as they can: nor that boys who have acquired the makings of a good scholar at Eton or Harrow should give evidence of the obvious fact that they know the elements of their special subject. I take it that the object of making Greek compulsory is to give notice to the world at large and, in particular, to the educational world, that an acquaintance with that part of Greek which can be readily taught to all boys at any of our higher schools, is regarded at Cambridge as indispensable to a properly educated man. The classical languages must be studied to some extent by everybody who aspires to a certificate that he is a highly educated man: in other words to a degree. This is the rule at Cambridge. The retention of Greek in the Previous Examination echoes, in academic language, the opinion which is not by any means extinct, however old-fashioned, that a knowledge of Greek, as well as of Latin, forms part of a “gentleman’s education”.

The main object of making Greek compulsory for all aspirants to Cambridge degrees does not directly concern the studies of Cambridge Undergraduates at all. It concerns the studies of those who intend to become Cambridge Undergraduates. It concerns the higher education, not of young men, but of boys. The reiterated declaration of the Senate that it will stand by compulsory Greek, is addressed not to Professors, Lecturers or Tutors at Cambridge, but to schoolmasters. Cambridge, one of the greatest educational institutions in the world, and, I think, one of those bodies to which has been entrusted the preservation of valuable studies too likely to be decried and forgotten in these busy mercantile times, has spoken and will, I trust, speak again, not only to the public, but specially to schoolmasters. The substance of her declaration is this:—that at all schools which aspire to give the highest education and to form the antechamber of our great Universities, Greek must be taught. Those who have not learned Greek at school must either do without a degree, or pay for the inadequacy of their education, by learning enough Greek to pass the Previous Examination, before they settle down to their chosen line of study.

Is Greek to be taught as a matter of course at our leading public schools? That is the issue: and that is known to be the issue. Several of the leading supporters of the proposed change have avowed as their object, not the removal of inconveniences for students at Cambridge, but the liberation of schoolmasters from a disagreeable necessity. And, if the attack on Greek derives much of its energy within the University from the hostility felt towards the old studies by the promoters of the new, it no doubt owes its impulse from without to the dislike a large number of schoolmasters—though it would seem from a recent vote at a head-masters’ conference that they are a minority—to the retention of Greek as a practically compulsory study at schools.

Ought every really well-educated man to know, or to have known, something of Greek? Is it right that a father who sends his son to a first-rate school should be told that he will have to learn Greek? These are the questions on which there is a real and important difference of opinion among men of sense and judgment. I propose to answer them in the affirmative and to give my reason for so doing.

There is a point, to which I shall return later, but to which I must advert now, for the purpose of laying down a general proposition which is indispensable to my argument. I must be allowed to state, deferring, till a more convenient part of this essay, my reasons for so stating, that in my opinion the study of Latin and the study of Greek must stand or fall together. I have no doubt that the abolition of compulsory Greek would be followed by the abolition of compulsory Latin: and I could quote very eminent names, on both sides of the present controversy, in support of my view. I postpone the discussion of this point for the present: and proceed to explain why, on general grounds, I desire the study of the “dead languages” to be retained as indispensable to the best education which England can offer.

I believe that the “dead languages” are not dead. They are living. There is no language—not English, which is understood from Alaska to Cape Town, and, literally, from China to Peru—not French, which is read and talked by every educated man in Europe—which has given such proofs of vitality in the truest sense of the word, as Latin and Greek.

Greek and Latin live. They live in the first place by the existence of modern tongues which more or less exactly reproduce them, and for the study of which, especially in the case of Greek, an acquaintance with the ancient forms gives immense facilities. They live because the books which are written in Greek and in Latin are still eagerly and constantly read by thousands of readers throughout the civilized world. Do not the same emotions which thrill the reader who surrenders himself to the magic of Shakspere, still wake in the heart of him who studies the words put together ages ago by Homer and Aeschylus, by Lucretius and Virgil? Is it a dead language in which Horace furnishes the apt and unsurpassed expression of a thousand thoughts familiar in our mouths as household words? Is there any sign of death in the flexible and accurate language in which the Fathers of the Christian Church still speak to students of ecclesiastical lore, or the great jurists of Justinian’s reign still expound the principles of their noble science for the benefit of youths studious of learning? The power to endure through long series of centuries is a sign not of death but of vitality: and it is an abuse of terms to speak of a language as dead which has preserved for us in all the freshness of their original fire, those scattered remnants of Sappho which sparkle like jewels on “the stretched fore-finger of all time”. An abuse of terms: for it is no answer to my criticism to say that “a dead language” is merely a convenient synonym for a language which is no longer currently spoken among men. The phrase, like most phrases, inevitably implies a certain attitude towards the objects to which it is applied. Whatever meaning it may originally have had, it serves to fortify and emphasise the contemptuous attitude towards classical studies which belongs to the latter part of our own century: and, to do their work properly, the words “dead languages” should be amplified, as in men’s minds they often are, into the more complete and rounded phrase fathered on Cobbett by the Authors of the Rejected Addresses. I prefer to speak of Latin and Greek as par excellence “the living languages”: holding that no languages are more truly alive than those by the reintroduction of which into the studies of educated men, Europe was rescued from darkness and brought into the paths of reform, and which have ever since been heard in the Courts and class-rooms of our great centres of education: and freely accepting that attitude towards Latin and Greek which the reversal of the common phrase may seem to imply.

The study of Latin and Greek has been and is one of the great humanising and developing powers of modern times. Those who dispute this opinion must either maintain that the revival of the study of these languages in the fifteenth century did not possess the importance, nor produce the results, almost invariably attributed to it: or allege that the learning which then revived has done its work and discharged its office, and that we may now relegate “the dead languages” to the position of obscure phenomena to be minutely investigated by trained specialists, interesting only to one another, and may trust to some other educational pabulum for the due development of posterity. Did the “revival of learning” in Europe owe nothing to Latin or Greek? or did it never take place? or did it do no good? Or, on the other hand, is it the case that boys now in the nursery, or not yet born, have or will have hereditarily acquired whatever permanent residuum of their ancestor’s studies has any value, and, “heirs of all the ages”, can afford to dispense with the intellectual equipment which was so valuable to their half-developed predecessors? Let the man for whom either horn of the dilemma has no terrors make his pronouncement to that effect: and he shall be answered. Meanwhile I leave the general aspect of the question there.

CHAPTER II

I proceed to the consideration of Greek, apart from Latin, as an educational factor: and I think it right to interpose, at this point, some remarks of a purely personal nature, which are none the less necessary to be stated. I do not claim to be, I will not say a finished Greek scholar, but even a Greek scholar of average capacity among those have made classics a subject of prolonged study during boyhood. I never worked at Greek, except incidentally and for my own pleasure, after I had left school. I never competed in any examination for which a knowledge of Greek was required, after that in which I obtained an Entrance Scholarship at Cambridge. I do not read Greek easily: nor write it at all, though I daresay I could hammer out a score of Iambics if my life depended on it. It is therefore with diffidence that I speak on the subject. Nevertheless I do not hold that my lack of scholarship precludes me from taking part in this controversy. On the contrary I think it is in certain ways a circumstance adding weight to my remarks: first because I cannot be accused of any professional prejudice in favour of studies which I have long abandoned, in which I never gained any particular distinction, and which have no direct connection with those subjects on which I now give instruction for gain: secondly because I claim, so far as is consistent with due modesty, to be the sort of person whose interests are principally concerned in the question now at issue. If some such vote as is now proposed had been passed twenty or thirty years ago, and had been followed by such further measures as the advocates of the change desire, it is as likely as the result of an unfulfilled condition can be, that I should never have learned Greek. “And you would have lost nothing by it” an opponent might unhesitatingly rejoin: and thereupon the question at issue between us becomes clear and definite: for I think I should have lost a great deal.

I write on behalf of those who are not good scholars, but can only claim to have got, while at school, in fair measure, such educational advantages as the present system offers to those boys who show no particular bent for any special study, but work, or abstain from working, at the ordinary subjects at which they find that they are expected and encouraged to work. I do not write on behalf of born scholars. They, no doubt, will always, under any system, find the way to the Greek and Latin books and study them, sooner or later, with avidity and success. I wholly understand the position of those who say that Greek, if its study be made voluntary, will be learned by all who have the making of first-rate scholars in them, and will be lost to none but those whom nature did not mean for scholars. But between those to whom the study of Greek brings real scholarship, and those to whom it brings nothing but tribulation and confusion, there is a large class who attain in it that reasonable degree of competence which they would secure in any subject prominently put in their way throughout their school days, and therewith, as I believe, many advantages, not growing on every branch of the tree of knowledge. These are the boys for whom I wish to save Greek: and I believe it can only be saved by being made compulsory, as an introduction to academic education and a University degree.

I have said that I am not, and never was, never shall be, and never should have been a Greek scholar. But I began Greek before I was ten, and did not leave off studying it daily during term time until I was nearly twenty. I am afraid to reckon up the time which I must have devoted to reading Greek, writing Greek, and endeavouring to master the rudiments of Greek grammar. I think it highly probable that I have forgotten more Greek than I remember. I cannot point to any practical or pecuniary advantage derived by me directly from the study of Greek. But I can honestly say that I do not regret a single hour of those which I spent in the study of the language: nor is there any sort of knowledge which I would rather have imbibed than even that part of my boyish knowledge of Greek which I have forgotten. I must apologise for the personal tone of this assertion. It is as well to present things from a point of view with which one is familiar: and I attach value to my own case, as I have already said, because I think that I speak in the name of a large class, and one of which the interests are vitally concerned in the question now before the University.

I wish to estimate the value of a knowledge of Greek, as a part of the intellectual equipment of a well-educated man: and I particularly wish it to be understood that by “the value of a knowledge of Greek” I mean the value not merely of knowing Greek—which may at any given moment be practically nothing whatever—but of having known Greek, which I take to be always considerable. The first merit which I claim for this knowledge is the perfection of Greek, in many respects, as a language. I shall not presume to enlarge on this subject. Others have dealt with it far better than I could pretend to do. I suggest the statement that ancient Greek is a marvellously subtle, flexible and ingenious language, and contains mechanical niceties and intellectual devices not to be found in any modern language, as a commonplace which has never been denied: and if any supporter of this or any Grace denies the proposition, I will deal with him hereafter: unless indeed his audacity (or ignorance) provoke the entrance into the lists of some champion better equipped than myself for such a controversy. Greek is a beautiful language in more ways than one. It approaches, I suppose, more nearly than any other language, to perfection in a certain line. Of languages which depend upon inflections, whether of verb or noun—which approach recondite meanings by the almost unlimited variability of a single word, rather than by the coarser method of multiplying auxiliaries and prepositions, it is, I should conceive, admittedly supreme. It is a masterpiece of the human intellect. Perhaps this is not the best way of talking and writing. Perhaps the coarser, rough and ready methods of most modern languages bring language more immediately into harmony with the thoughts of a rather commonplace race: and provide a more effective instrument to the broker on the Stock Exchange or the bagman on his rounds. If our millennium is to be what Carlyle called “a calico millennium” and the industrial or economical aspect of things is wholly to supersede not only the military but the literary and philosophical, Greek may become more than ever a thing of the past. But none the less Greek is a beautiful language: a “joy for ever”: it is the very best language ever constructed upon a plan which is, at worst, the second best, and which many hold to be in some respects the best. Now to know such a language as that,—nay more to have known it, or even to have spent hours or years in studying it, and yet never to have known it at all, is an advantage to a man quite independently any practical good it might do him. Let me appeal, by an illustration, to the man of science. If I study a dynamo machine, or a gigantic railway bridge, until every piece of its mechanism, and every function of all its parts has been explained to me, and a good part of them understood, may I not be the better for the process, though I never have occasion to generate electricity, or to carry a railway across a river? Nay, though I ultimately forget the details of what I learned, may not my mind be an apter instrument for future tasks, because it underwent that piece of training? So with Greek. The student of so marvellous and admirable a product of the human mind, gains much by his study, though he never turns it to any practical use: and studies other things more rapidly and effectively, because of the training that study gave him, even when he has forgotten how to write an Iambic, or to do a set of “derivations”.

I may perhaps be pardoned if I trench for one moment on a subject too obscure and difficult for any but a specialist. I should like to arrive at certainty upon the subject of “forgetting”. Does one ever quite forget a thing? I doubt it. The impression once received is somewhere, till death at all events. All that one needs is to be reminded of it. Who cannot cite a score of instances of trivial matters forgotten for many years, and recalled in all their original distinctness by some incident which “reminded” the person of what was forgotten: which, in other words, revealed the piece of knowledge long obscured by the superincumbent deposits of subsequent years? Therefore if a man is said to profit nothing by having learned Greek because he has forgotten it, I reply, for one thing, that he has not forgotten it, and may be reminded, at any time, of all the Greek he ever knew: and for another thing, perhaps of more practical import, that his latent knowledge of Greek, of which he will possibly die unreminded, is associated with aptitudes, capacities and tastes, which sprang from, and have survived his actual familiarity with the language.

Besides the merit of flexibility, elasticity and ingenuity, which Greek will surely be admitted to possess, I would briefly advert to the sonorous, almost melodious character of the words of which it is composed. Here again I will not encumber my argument with proofs or illustrations. Proof of such an assertion is indeed, in the nature of things, impossible: and as for illustrations, I am not competent to supply them in an efficient manner, and if I were, I have no reader acquainted with Greek who cannot supply them for himself, or who needs to have such a truism illustrated. To the ear, as well as to the intellect, to the student of aesthetics as well as to the student of philosophy, Greek is a beautiful language. The power of Greek poetry to please the ear, however remote the pronunciation of the reader from that of the writer, and whether the accent be placed as we place it, or as the modern Greeks place it, has been pointed out over and over again: as has the fact that the pleasure of listening to the sonorous roll of Homer’s hexameters, the stately march of the iambics of Aeschylus, or the delicate ripple of Anacreon’s songs, is not denied even to those who are wholly ignorant of Greek. I know no other language of which this has been so often and so truly said. We, in Cambridge, have seen large audiences, in great measure composed of persons wholly ignorant of Greek, moved to emotion of which it would be discourteous and censorious to doubt the sincerity, by the representation, under circumstances almost as different as possible to those contemplated by the authors, of Greek tragedies written two thousand years ago. Such is the power of the beauty and sweetness of Greek words: and the language to which these qualities have secured immortality is spoken of as a dead language!

Akin to the merits of Greek to which I have already referred is a merit of which I should like to speak at considerable length, were it not that its proper discussion would lead me too far from the subject under consideration. I refer to the extraordinary richness of the language of the Greeks in metrical possibilities, and of the literature of the Greeks in actual metrical experiments. Metre is the foundation of all poetry, and is of incalculable importance in songs, and more or less indirectly in all kinds of musical composition so far as melody, apart from harmony, is concerned. The great storehouse of metrical devices is Greek literature. The Latin poets derive all their metrical lore from the Greek poets. In the study of modern metres nothing is more interesting than to observe the similitudes and differences, the echoes and contrasts, the reproductions which are repetitions and the reproductions which are totally new departures, furnished by the languages of to-day and the languages of the ancient world. The subject is extensive, intricate and special: but I do not hesitate to say that the excellence and importance of Greek in its metrical aspect alone, are sufficient to make it a subject better worthy of general study than many others which find more or less eager adherents.

Hitherto I have examined only such of the merits of Greek as an educational instrument as depend upon the language itself. These however are but a small part of the merits which it must be admitted to possess. Let it not, however, be forgotten that they are a highly important part. There is a comment to be made by opponents upon much of what is to follow, which cannot be made upon what has gone before. When I speak of the value of Greek literature and Greek history, I may be told that this is of no importance in a discussion of compulsory Greek: because all that is to be known of the ancient world can be read either in modern books or in translations of ancient books. I hope I shall not be without an answer to this objection: but at all events it cannot apply to what I have already said. Such educational merits as belong to Greek, in its capacity as a language, cannot be reached except by a study of the language itself.

It is impossible to study a language and not to study its literature: and it is impossible to study the literature of a sensitive and eloquent people and not to study the people themselves. A boy who reads Greek regularly for ten years, reads, of necessity, a number of Greek plays in which the religious feelings of the people, their patriotism, their superstitions, their belief as to the past, their political associations, and their judgments on moral and social questions, inevitably find expression. He reads portions of histories which bring to his mind a more or less vivid representation of the picture of the past which belonged to the average Greek of the historical epoch. He reads portions of philosophical works which give him some notion of the sort of problems which occupied the mind of a speculative Athenian, and the sort of answers for which he was accustomed to look to the questions which he asked of himself, and of his instructors. Just as a fairly intelligent boy picks up from stray conversations, books and newspapers a general idea of the course which political events are pursuing in England and Europe: of the character belonging to the several epochs of modern history: of the contents of the great plays of Shakspere and the epics of Milton, even if he has never read them: and of the sort of views which are to be expected from Darwin, or Spencer, or Newman, though he could not give the names of their works: so the schoolboy who reluctantly opens his Xenophon or Thucydides or Poetae Scenici at the appointed hour, is very gradually and almost unconsciously acquiring a general feeling of what Greek life, and Greek modes of thought, and the course of Greek history, and the tone of Greek literature were, which will be to him a possession for ever, and which is none the less a valuable piece of mental furniture because it is necessarily incomplete, and almost certainly inaccurate.

And here I come upon the great and distinctive merit of Greek literature as a subject of continuous study when the mind is fresh and susceptible of new impressions. There has never been since the world began, and there can hardly ever be again, a period so suitable for collective presentation to the mind of a boy as the flourishing period of Greek history. It is the brief but inexpressibly stirring period when a highly sensitive, and intellectually brilliant people were, and knew themselves to be, at their very best. The country was small: the people were necessarily few: of the actual population a great proportion were slaves and lay to a great extent outside the account, as far as matters of literary, artistic, philosophical, or political importance were concerned. The outside world, the world beyond Greece, could be almost wholly neglected. It was a dark region, teeming no doubt with undecipherable possibilities: lit up here and there with the blaze of gorgeous and barbaric tyrannies, going with a blare of trumpets and a gleam of banners the way to inevitable dissolution: but upon the whole no more than the sombre and uninteresting background of the most complete and brilliant picture the world has ever seen. The men who directed the affairs of a Grecian community were known by name, if not by sight, to every free citizen. The eminent philosophers and famous poets were seen every day in the market place, or at the assembly hall: they did not spend the working part of their life in an unknown house in a more or less dingy suburb and devote their annual holiday to an excursion to the Alps or across the Atlantic. Every one was known. Every one was a citizen. Every one discharged recognised functions. The little world in which they lived was open to the inspection of all: and every figure in it could be seen at work. Only in such a community could Aristotle have laid down as obviously true the remarkable proposition that it was a necessity for a state not to be too large for its citizens to meet in a single hall. Most of the states of Greece realised this condition. Those which did not were regarded as over-grown and almost necessarily barbaric: their actual dimensions being perhaps inferior to those of a large English county.

What was the result? This: that a race of persons gifted beyond any others with the power of self-portrayal, found themselves so posed and grouped that nothing was easier than to portray themselves both effectively and completely. So it has come about that a British schoolboy, dividing his time between his books and his games, much to the disadvantage of the former, can nevertheless in five or six years get such a picture of Greece, and such a recognition of the Greek spirit, as he will never get, even with the advantage of being personally present to conduct his investigations, of the life and genius of any other nation.

The imperfect condition of ancient Greek literature at the present day is rather an aid to the student than otherwise: because it puts actually within his grasp, instead of at an incalculable distance from him, the possibility of practically knowing all there is to be known about the people, their history, their habits and their feelings. Let a boy who is fairly familiar with the Greek language collect his classical books and begin to re-read them, with a view only to their contents, as he reads Shakspere or Dickens: neglecting philosophical niceties, doubtful readings, or archaeological speculations. Let him read twenty tragedies and ten comedies: two or three hundred pages of epigrams, odes, fragments and miscellaneous pieces: three epic poems no longer than Paradise Lost, and much easier than the Ring and the Book: two history books, far shorter than Macaulay or Hume: and a dozen or so of not very elaborate philosophical treatises: and what a tremendous hole he has made in Greek literature! This remark may seem irrelevant to a great scholar: he cannot bring himself to regard a play of Aeschylus or a dialogue of Plato, over which he has pored for long years, and which will afford the subject of equally protracted studies in the future, as a thing to be skimmed by a schoolboy in a few hours for pleasure and superficial information. Nevertheless the thing is evidently possible and far from unprofitable: and it is no small point in favour of Greek, that the language once learned, and the spirit of the people once appreciated, as it should be, after years spent at a school where Greek is regularly taught, nearly all the masterpieces of the literature can be run through a second time in a period which would not serve to make an appreciable inroad into the literature of any other highly developed and civilised community.

To complete the catalogue of the merits which Greek possessed as a means of education, would tax the eloquence of the most gifted writer, and the knowledge of the most profound scholar. I can do no more than faintly indicate the topics on which it would be his duty to enlarge. After all, the inherent merits of Greek literature are not likely to be denied. Homer still holds, and will continue to hold, his place in every man’s opinion, at or very near the head of all the poets whose works we know. Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes remain at an immeasurable height above any other group of dramatists produced within so short space of time by a single community. Only one name has ever been placed above theirs: and Shakspere admittedly stands quite alone. It may serve to show what a gulf separates them from other rivals, that the group of dramatists who wrote under Louis XIV of France has probably been compared with them more often than any other. No philosophical writer has ever claimed, nor have his followers ventured to claim for him, a literary merit comparable to that of Plato: nor can any two names be mentioned concerning whose importance as philosophers there is anything like the consensus of opinion, which assigns a foremost place among those who have directed the course of human speculation, both to him and to Aristotle. The glory of Thucydides and Herodotus shows no sign of waning. But it is idle to state in a catalogue of truisms the oft-told tale of the greatness of Greece, for which the world furnishes no parallel. Eliminate the Hellenic chapter from the history of the world: destroy the literary masterpieces to which reference has been made: let there be no remnant of the noble edifices which the Greeks reared, no instance of their almost incredible skill in the sculptor’s art: no clue to their ways of thought or their view of the world: no record of the great men with whom the world of action was enriched from their ranks: no memory of the wars they fought, the invasions they resisted, the colonies they planted, the patriotism with which their hearts were fired: the enthusiasm which made their great men teachers and rulers among a race of heroes: take all this away, and have you not torn from the history of mankind its brightest page and robbed the world of a large proportion of the feelings and memories by which it has been ennobled, encouraged, instructed and refined?

If I am told that all that is to be said about Greece and the Greeks is to be found in a number of excellent and accessible modern books: that Homer has been translated by Chapman, Pope, and Lord Derby: that the best portion of Thucydides is incorporated in Grote: and that Plato and Aristotle can be adequately studied in the works of Oxford and Cambridge translators: I can only reply with honest conviction if not with argumentative force; first that the literature of no country can be studied with so much profit, pleasure and insight in a translation as in the original: secondly that there would be very little chance of the study of Greek literature and Greek history continuing to be general, if it were contained in books not essentially distinguishable from ordinary English books on other subjects: and lastly that I am perfectly certain that no one of the celebrated and meritorious translators of Greek would recommend the universal adoption of his version as a substitute for the original.

CHAPTER III

I have reserved for the last in my list an educational merit of Greek which might seem more proper to be classed with those dependent on the nature of the language itself, which I considered before dealing with those dependent on the nature of the books written in the language, and on the things and people with which these books are conversant. But I reserved this topic for the last, because it will inevitably lead the way to a general discussion of the nature of education and to a statement of the belief on which the movement in support of Greek is really founded. The topic is the difficulty of Greek. I think the language is a good one to teach boys precisely because it is a difficult one to learn. I believe that the numerous difficulties which make Greek lessons a trouble and a torment to stupid boys, constitute part of a most wholesome discipline. The rules about cases and genders, moods and tenses, declensions and conjugations, prepositions and conjunctions, which a boy is compelled to learn by heart, to apply rigorously and in detail, and realise continuously: the deductions he must grasp: the inferences he must draw: the analogies he must perceive: in short the rigours of syntax and the severities of accidence: all these difficulties, harassing and irritating as they may seem from day to day, are eminently salutary in the long run. To learn a modern language which is acquired partly by guess-work, partly by imitation, partly by its close similarity to English, may be a more pleasant kind of work, but is certainly a less efficient training, than laboriously and exactly to school oneself to read and compose a language in which every step, from learning the alphabet to mastering the last intricacies of syntax, must be patiently and accurately made. One boy may know enough French to live by himself in Paris while knowing as little of French grammar as he does of English: another may know enough Greek to construe the easier parts of Xenophon, and just enough of the mechanism and vocabulary of the language as will see him through that operation. The former boy has doubtless the more showy and apparently the more useful accomplishment: but the latter is the more likely to enjoy the advantage of not being wholly uneducated.

For, what is education? Here we touch the kernel of the matter. However the question need not delay us long: for in order to decide on the educational value of Greek it will suffice to lay down a general principle without going into questions of detail, or developing argumentative elaboration. The object of education is, in my judgment, to strengthen the mental faculties of the person educated: to give him the power of acquiring knowledge: of seeing where difficulties lie and how they can be solved: of distinguishing the immaterial from the essential: of estimating by how much labour a certain task can be performed: of knowing how to begin and when to stop: of performing all the operations of learning at once soundly and rapidly. Add to all this the power of observation: which brings with it, so far as the mental structure of the individual allows of it, the power of accurate memory: and the power of expression: which is little more than an accurate knowledge of language coupled with imagination and insight; and you have a perfectly educated man. Find me a lad of eighteen who possesses, in fair measure, all the gifts which I have enumerated: and I will declare him to be well educated, even if he knows no language but his own, is ignorant of the multiplication table, and has never heard of any one of the sciences. Of course it is practically impossible that a well-educated boy should be absolutely ignorant; because some means or other must have been used to train his mind; and his growing powers of observation and memory must have enabled him to retain a knowledge of the subject-matter of his studies. But his knowledge is accidental and irrelevant to the question whether he is well educated. I do not care for his knowing the most rare and curious things: I do not mind his not knowing the most ordinary and obvious things. What I do care about it is the condition of his intellectual faculties, and his capacity for observation, acquisition, arrangement and expression. Given all these, he is well educated: and it will not be long before his ignorance vanishes.

For when a boy gives up the fragmentary and protracted studies of his schooldays and ceases to crawl unreflectively from Tacitus to Herodotus, from Molière to Goethe, or from Geometrical Progression to the Parallelogram of Forces, taking in knowledge in minute doses, and passing from one unexhausted trifle to another in obedience to scholastic routine: when he quits this system for the life of a great University, or for the outside world, a complete change in his intellectual life takes place. Up to now he has studied things, not for their own sake, but for the sake of the gradual process by which his mind has been unconsciously transformed from that of a boy to that of a man: by which, in other words, his education, good, bad or indifferent, as the case may be, has been carried out. Henceforth study, whether as the main pursuit of an academic career, or as the occasional recreation of a life otherwise occupied, will mean the direct, conscious and rapid acquisition of knowledge. He will now learn in a week what he previously learned in a year. With the aid, perhaps, of an experienced tutor, he will extract in a few hours the essence of a book which might previously have afforded, in one part or another, materials for intermittent and inconsequent studies of innumerable afternoons, which would still have left whole regions unexplored. He will read at a sitting a Greek play of which about four-fifths was then doled out thirty lines at a time thrice a week for thirteen weeks, the other fifth remaining wholly unknown. He will at last come to understand, what dimly puzzled him in his chrysalis state, how men manage to acquire such enormous masses of learning as sometimes fall to the lot of one student, and peruse in a dozen years thousands of volumes each one of which appears to the schoolboy’s mind to stretch far beyond the compass of the labour of a complete school time.

I know well that this change in a student’s attitude towards his studies does not take place in its entirety at the same point in the life-time of every boy. I only say that in the life-time of every reasonably intelligent man there occurs a period more or less condensed or protracted in special cases, somewhere about the end of his schooldays, when the possibilities of daily and yearly achievement in the way of learning are revealed to him, and when (if he knew it) the conscious and effective study of things for their own sake, replaces the slow and unconscious acquisition of mental capacity, by means of the laborious and not very effective study of things for the sake of their educational value. Sometimes this change synchronises with the transference from a school to a university: sometimes it precedes or follows that transference at an appreciable interval. When a boy goes straight from school to the business of making a living, the change is sometimes first made apparent by the rapid and effective manner in which he learns his trade or profession. Or, perhaps, the boy leaves his school for a professional “crammer”, who undertakes to make him capable in a given time of getting a certain number of marks in a given examination. The “crammer” is successful and gets another name to add to the list of victorious candidates which he circulates by way of advertisement: and the boy’s parents begin to cry out upon the dilatory ways of public schoolmasters: and to lament that the boy’s time was wasted at school, and that he ever went anywhere except to the intelligent and efficient “crammer”. What the boy’s parents fail to see is this: that the inevitably slow and tedious process at school taught him, if not very much of the subjects comprised in the examination, at all events the power of assimilating and utilising the facts which the “crammer” flashed upon his eyes, with a rapidity which would have dazzled and confused him, but for his long and painful training at school.

It has been said hundreds of times before, and is true, that the great object of a boy’s education is to “teach him to learn”: and to provide for his mind a series of exercises which shall strengthen it, and develop its useful qualities, as much as gymnastic exercises strengthen and develop the body. If this theory be true, it matters little what a boy has been taught, so long as he has learned the one essential lesson:—how to learn. If everything that ever was said in disparagement of the “dead languages” were true, and if it were also true that their difficulty, and the certainty of getting work out of boys by means of them, rendered them the most effective form of mental gymnastics, it would still be reasonable to insist that they should be taught in all the foremost public schools in the country. Let it be granted that Greek can never be talked to any good purpose: that Greek will never, as a matter of fact, be written or even read by a man busy with a thousand occupations: that whatever picture of Greek manners and Greek thought may have found its way into the boy’s mind will fade entirely out of the man’s: nay more that a boy will rapidly forget every word of Greek he ever knew and even the letters of the Greek alphabet: grant all this—and it is far more than any reasonable man will ever ask us to grant—and the study of Greek may still continue to be valuable and important, if it really possesses exceptional merits as a means of mental training.

I contend that the difficulty of Greek alone renders it far better than a modern language, or than any subject that can be suggested, except, in a less degree, Latin, and some branches of mathematical studies, as a means of mental training: and that the sort problem it forces a student to solve, and the kind of questions which the study of it brings to his attention, have a direct educational value as processes to be undergone, apart from the general value of Greek as an acquisition likely to be retained. I do not wish however to push this point so far as to injure my own argument as well that of my opponents. I use it to answer those who will not accept the answer I have given them already, and who adhere to the view that Greek is “no use”: and I endeavour to show that, even a practically useless language, and one which wise men make haste to forget, might have a high educational value, since education is mainly concerned with providing a gymnastic training for the mind. It is evident however that schoolboys get some knowledge from their education, and no doubt it is as well that that knowledge should not be valueless. I have given reasons for thinking that a knowledge of Greek is exceedingly valuable in itself. I may further observe that the compulsory study of Greek in public schools, in so far as it exists, does not prevent the study of numerous other branches of knowledge. A boy does not as a matter of fact leave even the most conservative of our great schools without some knowledge of history, geography, French, German, chemistry and geology, as well as classics and mathematics. Compulsory Greek does not therefore mean the complete neglect of these subjects. Indeed there are not a few who think that the introduction of numerous subjects into the boy’s curriculum has already been carried too far: and would deplore the abolition of Greek, if for no other reason, because the removal of a study which takes up so much of a boy’s time would leave room for an incalculable influx of new subjects to smatter in.

It would be deemed too absurd and reactionary for belief if I advocated the adoption of the system by which boys were once taught nothing whatever but Latin and Greek: taught that well: and left plenty of leisure to employ as they chose. I do not advocate it. I content myself with observing that some of the best educated Englishmen that have ever lived—and the list, which begins far back, could be completed by the names of men now living—were educated precisely upon that system. But I do not wish to put myself unnecessarily at issue with the spirit of the age. Let it be granted that it is an indispensable necessity of a good system of education to give a boy a little knowledge of many subjects. Time can be found to do this without neglecting the far more important duty of training the mind; and, as experience proves, without neglecting Greek.

Having considered the effect which the retention of Greek may have on a boy while he is at school, let me, for a short time, follow the boy to the University and see what effect it has upon him there. The only effect which it has necessarily and directly is that he must pass, if he has not already got a certificate of efficiency at school, an examination for which some knowledge of Greek is required. To the great majority of Undergraduates this effect is insignificant. A very moderate knowledge of Greek is enough to give the boy as good a chance as his faculties allow of passing the Previous Examination at once. Of course there are boys, and sometimes boys by no means stupid, who habitually fail to pass examinations, for reasons which remain for ever unknown to themselves, their parents and their friends. There are other boys so stupid that it is, I suppose, desirable that they should fail: if not, why should there be a Previous Examination? I own that that question is beyond my power of solving riddles: I do not know why there should be a Previous Examination: but then I do not even believe in the necessity of Triposes, so that I suppose my views on competitive examinations are too heterodox to be put forward. But if there is to be a Previous Examination, one of its objects must be the failure of the very stupid: or, in the jargon of the day, the non-survival of the unfittest. If then some students are meant by the authorities to fail, and others are destined by the Gods to fail, I suppose that they would as soon fail in Greek as in anything else. Probably they fail in other things as well. I have never seen any statistics as to the favourite subjects for failure. No doubt the substitute for Greek, if it is ever produced, will not baffle the powers of candidates bent on collapse.

The boy who has learnt Greek at school then has no reason to complain of that part of the Previous Examination for which a knowledge of Greek is required. Either he passes it with no greater expense of trouble than is involved in going to the examination room: or he passes it by means of a few weeks’ study of the kind to which he has long been accustomed: or he fails to pass it with the indifference bred of repeated experiences of the same kind. Certainly if he possess any ability whatever, the boy who learned Greek at school is able to devote a great part of his time at once, and the whole of it before very long, to whatever special studies he may select at Cambridge.

But how does this part of the Previous Examination affect the boy who has not learned Greek? Here is the one University grievance which the present proposal is intended to correct. It is not a very grave one. The youth who has not learned Greek, must learn it. No doubt he will find it rather difficult, because he is, in all probability, a badly educated youth. But although he has not learned Greek he has presumably had a mental training of some kind, and, if there be any good stuff in him at all, has learned something of the art of learning. I can call to mind instances of Undergraduates at Cambridge who learned Greek thoroughly and carefully for their Previous Examination, who never remitted for a day their other studies, who never over-worked themselves, who passed the examination with ease, subsequently distinguished themselves in their own subjects, took a brilliant degree, and never for an instant regret the hours spent on Greek when they were freshmen. But let me then put the case more strongly against myself. Let me admit that some youths do not take this intelligent and satisfactory course: that they resort to the lowest tricks of the “crammer”, and the meanest devices of the fabricator of “artificial memories” in the order that, without, in any intelligible sense of the word, “knowing Greek”, they may enable themselves to beguile the examiners into thinking that they do. Let me suppose even that a man gets through the examination without being able to read Greek, because he is enabled to recognise, by its general appearance, a passage of which he learned the English by heart from the version of Mr Bohn. Add to this that the man afterwards forgets all the Greek he did learn, loses a class in his Tripos by the time wasted in manufacturing false evidence of his knowledge of Greek, and bitterly deplores the time so wasted till his dying day. Here, I will admit, there is a grievance. But it must be borne with philosophy. The possibility of such occurrences is the necessary result of a system indispensable to the general study of Greek in schools. If Greek is optional at Cambridge, Greek will cease to be generally taught to boys. Therefore those lads whose parents or teachers choose to leave them ignorant of Greek, must pay the penalty of learning it as freshmen, or must forego the privileges which Cambridge has a right to concede only on her own conditions.

But when the Previous Examination is once over, and for nine men out of ten it is no great matter, Cambridge affords perhaps unrivalled opportunities for specialisation. During the terms which elapse between passing the Previous Examination and going in for the Tripos, a man can work exclusively and continuously at the class of subjects in which he naturally takes an interest. The bisection of a good many Triposes has somewhat multiplied the restrictions under which he must work, necessitating a general study on broad lines during the first part of his career, and permitting the minute investigation of one branch during the latter part. But a wise man will not allow himself to be put very much out of his intended course of studies by Tripos regulations: and if necessity does compel him to conform to the rules by which the largest number of marks can be obtained, he is after all dividing his time upon a principle suitable to the average student, and much commended by experts: and in any case the whole of his time is devoted to the main subject of his interests and ambition.

Now comes into play the method of doing work which belongs to the man as distinguished from the boy, and which steals half-perceived within the limits of his capacities with a rapidity and completeness dependent upon the excellence of his education as a gymnastic process. The progress which a man can make during three or four years’ arduous and continuous study of classics, mathematics, science, history or law, is so great as to appear absolutely incredible to a boy with his hazy reminiscences of the books which supplied provender for term after term, and year after year, and a general sense of apparent stagnation upon a very limited sea of learning. The reason has been stated already. The Undergraduate has been educated. He has learned to learn. He comes to Cambridge to use the power which his school education has conferred upon him. He comes there to acquire knowledge. His schoolmasters have taught him to observe, to remember, to coordinate, and to compare. His University Lecturers and Tutors should teach him—but many men do not really need much teaching—how to use to the best advantage the powers so bestowed upon him. Using these to the best advantage, he learns in a year more than he could have learned in seven years before he was educated. In three years he ought to acquire a really valuable fund of knowledge. It is possible, though it is in no case otherwise than unnecessary and undesirable, that the circumstances of his after life may be such as to prevent his acquiring any more knowledge, except from the newspapers, and from his colleagues in whatever trade he plies or pursuit he follows. The question “what does he know?” is therefore the essential question to be asked about a man who has completed his University Course. I have already said that I consider it to be an incidental and almost unnecessary question to ask about a boy at the commencement of that course. The question to be asked about him is “Can he learn?” If he can, any amount of ignorance is venial, because it is curable. If he cannot, no amount of such knowledge as is acquired in Schools is likely to be very serviceable, or to make up to him for being, in the one essential matter, an uneducated man.

The well-educated but ignorant freshman becomes by the time he takes his degree a thoroughly well-informed man: the way to become a master of one subject, and familiar, from the circumstances and conditions of University life, with the outlines of many others. More than that, his powers of acquisition and rapid mastery of subjects are strengthened by use, and he will go on learning new subjects, in leisure hours, or in holiday weeks, during the rest of his life. The ill-educated boy, with much knowledge, becomes at the end of his University course an ill-educated man with rather more knowledge: takes the first opportunity of forgetting what he has learned, and never learns any more.

For reasons already given I believe that a boy who has carefully, methodically and slowly studied Latin and Greek, is far more likely than a boy who has not done so to be well educated. He is therefore likely to possess the great essential gift of knowing how to learn: and he is not a bit less likely than his fellows to possess the incidental but not despicable quality of knowing things already. I contend that such a boy is the one who has the best chance of making the most of Cambridge and that he is likely to excel in whatever branch of study he may take up: and when I say that he will excel, I do not mean that he will obtain many marks, or gain a high place in examinations, but that he will arrive at excellence, in the truest sense of the word.

I say that this is true of all branches of study: no more of the study of classics itself, than of the subjects commonly supposed to be most remote from classics. I may here revert to a fact already mentioned: that several distinguished teachers of Science in the University are among the keenest opponents of the change now proposed: and I should like to state an instance of a personal nature not without weight in the present controversy. A professional teacher of several subjects comprised in the Natural Science School himself told me, that he had found it an almost invariable rule that the students who came to him with a knowledge of Latin and Greek, and the training that that knowledge implies, but wholly ignorant of science, make far more rapid progress than those who had devoted no time at all to the “dead languages”, and much to the study of science. The former soon caught the latter and passed them: because they understood the art of listening to what was said, seeing what was meant, and remembering what they learned: whereas the others had only a stock of knowledge which a well-trained student could have acquired in a month, and which had been deposited in their minds, by the superficial study of years, while they did not possess the knowledge of the art of learning which a classical education would have given them.

Who cannot find a parallel to this experience in his own recollection? Who does not recollect, for instance. men who have taken to medicine, after the labours of the Classical Tripos and rapidly caught and outstripped those whose whole education had been deliberately directed towards modern and scientific subjects from their boyhood up, but who had never learned to learn rapidly and efficiently? or lawyers who never opened a law-book till they had taken their degree, or even won their fellowship, and whose power of mastering a new subject brought them, in a few months, to the front while those who had made law their study for years toiled painfully behind? or Indian Civilians, admitted under the old system, who went straight from the taking of a brilliant degree to India, and soon knew more of the art of governing the country, and of managing the natives than men who had been for years specially trained in the subjects selected by the Government as most appropriate for a civil servant? Give a man the best general training in the world, to which, I take it, the study of Greek is indispensable: and leave him to train himself for this or that special function, whether in the world of thought or in the world of action. What sensible editor would not prefer a leader-writer who had distinguished himself in the Classical Tripos and never corrected a proof, to one who had left the modern side of a public school for the seminary of the ingenious gentleman of Fleet Street, who undertakes to initiate young gentlemen and ladies into the art and mystery of journalism by a year’s practical training?

I will add, from personal recollection, one instance which must occur to many Cambridge men besides myself. I remember that the most distinguished student of science of recent years, who attained with unexampled rapidity to a European reputation, whose early death was mourned in every University on both sides of the Atlantic, and who left as much valuable work behind him as would have done credit to a man spared to old age, was a classical scholar to begin with: and I heard from his own lips that he had no greater solace and recreation in a life constant study, and of continuous literary and educational labours, than to read the masterpieces of the ancient world in the language in which they were written. This is a solace which would be unquestionably denied in after life to a boy with a strong taste for science, if Greek became an optional study in our large schools.

CHAPTER IV

I hope that many of the arguments which the opponents of compulsory Greek are accustomed to use have been answered, in so far as they are capable of being answered without greater knowledge than I possess, in the foregoing pages. The views which I have expounded indicate, or at least imply, the attitude which I should take up towards most of the lines of argument which my opponents are likely to adopt. I wish however to deal directly with a few of the arguments which have been employed on the other side: though I am conscious that I do so at the risk of repeating myself, since the case for the reformers has been constantly in my mind while I have written, and the realisation of the answer which I know that I must expect, has no doubt led me in many cases to anticipate it by such a rejoinder as I am capable of making. I proceed to the detailed consideration of certain objections.

1:

It may be said that Greek may be properly taught, by way of intellectual gymnastics to young boys, but that from fifteen or sixteen onwards a boy ought to be allowed to follow his bent, and not to be hampered by uncongenial studies: and that consequently the period at which a knowledge of Greek ought to be compulsory arrives much earlier than the period of Matriculation at the University. Such an argument concedes the main part of my case, and leaves me at issue with its champion merely upon a point of detail. I should answer him by saying that the time of change from a school to a University ought to coincide as nearly as possible with the development from study for the purpose of training the mind, to study, with a mind well trained, for the purpose of acquiring knowledge: that, if the entrance to a University now comes too late to coincide with the internal change, we ought to revert to the habits of our ancestors and send boys to Oxford and Cambridge a year or two earlier than we do: but that, upon the whole, the present arrangement appears, from the generality of instances, to come pretty near to an arrangement based upon a design to catch the boy at the right moment, and that the length and character of the University course gives to every student ample opportunities for specialising to his heart’s content, so that he suffers no real damage by being forced to put up with a somewhat prolonged course of ordinary general training, and mental gymnastics suited to the average student.

But I can adduce, to one who goes so far with me as the objection under consideration, a far more forcible argument. If it be true that the study of Greek is a necessary ingredient in the best possible education, I submit that there is no power on earth which can cause the study of Greek to be carried on in schools when the parents and masters would rather let it be, except the influence, example, and, to speak the plain truth, coercion, of the Universities. And, if it is the Universities who are to see that those whom they admit to a degree are possessed of a knowledge of the elements of Greek, they cannot invariably apply the test at any period earlier than that of the Previous Examination. By the system of University certificates given at school examinations, whereby a clever schoolboy can win exemption from the Previous Examination, or from that part of it in which a knowledge of Greek is necessary, a year or two before he comes into residence, Oxford and Cambridge have gone as far as possible in the direction of affording to students an early escape from the necessity of knowing Greek. If a boy is brought up to matriculate who has never gone in for a certificate examination, or in any other way brought himself within the purview of the University authorities, there is no way of more speedily determining whether he has fulfilled the conditions prescribed by the University for participating in its privileges, than by causing him at once to go in for the Previous Examination. To give up the right of doing this, on the ground that the ideally best time for doing it is gone by, would be irrevocably to surrender the position of the Universities as the guardians of humane studies in these islands.

2:

The objection made by some scientific teachers that Greek does their pupils no good, and that the necessity of learning Greek wastes their time, has perhaps been sufficiently discussed already. Boys who have not learned Greek at the proper time are no doubt inconvenienced: and the reasons which justify and necessitate that inconvenience have been already stated. As to the study of Greek having been of no use, a boy to whom it was of no use is not likely to make much of science, or of anything else that he happens to take up in the way of intellectual study. If it is possible for a moderately intelligent boy to work at Greek for years without in any way fitting his mind for work, and strengthening his intellectual fibre, every statement of fact in this paper is an error, and every argument a blunder.

There is a remark sometimes made by scientific opponents of Greek to which it will not be out of place to advert here. It is urged that it is a pitiable and ridiculous thing for a boy to leave school acquainted with the dates of the battle of Aegospotami or the destruction of Carthage, and understanding the mechanism of a trireme and the value of a sesterce, but absolutely ignorant of the arrangement of the solar system or the structure of the earth’s surface: and that there must be something radically wrong with a system of education which not only produces, but appears to regard with complacency such a terrible and anomalous thing. The late Mr John Bright is alleged to have made a similar complaint about his colleagues in the House of Commons, who could round off their perorations with a fragment of a “dead language”, but not one of whom could state off-hand the whereabouts of Chicago.