Scott Strgacich

The Augustan Doctrine

The Pax Romana of the early Principate was a Roman peace, not a barbarian one. The settling dust of the civil wars revealed a vast Mediterranean empire. Ptolemaic Egypt was gone, now a Roman province. Galatia too, in the Anatolian highlands, was soon gobbled up. The emperor Augustus’ legions marched against the tribes of the Lower Danube. In northern Spain, the emperor’s men waged a decade-long conquest of the Cantabri of Asturias. In the wake of Antony’s fall, Rome’s boundaries were again expanding as they had in Julius Caesar’s day.

In this way, the foreign policy of Augustus seemed a return to the expansionary tendency that had long held sway over the old Republic. Having restored order within the imperium after the chaos and civil wars of the Late Republic, Augustus thought it was again time to look beyond it.

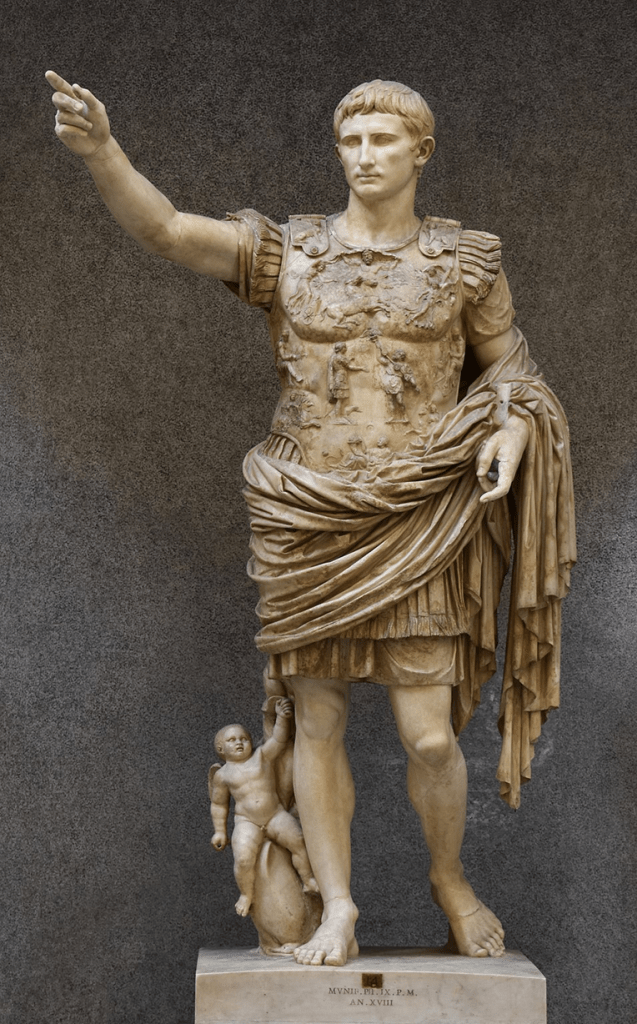

“Yet Augustus,” Suetonius tells us, “never wantonly invaded any country, and felt no temptation to increase the boundaries of the empire to enhance his military glory [bellica gloria]; indeed, he made certain barbarian chieftains swear in the Temple of Mars Ultor that they would faithfully keep the peace for which they sued.”[1]

Here, Suetonius implicitly draws a distinction between the motives behind Augustus’ warmaking and those of the Republic’s great captains. Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar were all steeped in a profoundly militarized politics wherein ‘military glory’ was the Republic’s most valued credential. Republican consulship and generalship went hand in hand, while the social strata of Rome’s voting menfolk defined the structure of the Republic’s armed forces until the Marian reforms of the early first century BC.

Thereafter, the landless poor were swallowed up into ever-personalized legion commands as the period saw what Henrik Mouritsen called “the exceptional militarization of Italy”.[2] Rome’s rapacious proconsuls increasingly waged war for its own sake – and in the hope of profit – a trend that culminated in Caesar’s bloody Gallic conquests.

If we are to take Suetonius at his word, Augustus, being the sole power in Rome, was motivated to maintain her national interests, not act within her politics. He reacted to the fall of the Republic with a mixed doctrine that saw territorial expansion as a mechanism by which to stabilize frontiers while still being anchored by a healthy fear of excess. Augustus’ wars in northern Spain and the Balkans, for instance, were circumscribed by geographical boundaries – the Bay of Biscay and the River Danube, respectively.

Augustus’ restrained eastern strategy bore fruit. Since the crushing defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the hands of the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, the raison d’état of Roman eastern policy had been vengeance, ideally realized by the recovery of the lost aquilae, the captured eagle standards of Crassus’ fallen legions. Twice during the late Republic, the Romans tried to regain them. First, Caesar amassed his legions in Macedonia, only to stop off at the Senate in Rome on the Ides of March and never leave again. His protégé Mark Antony then invaded the Parthian Empire in earnest, only to narrowly avoid becoming a second Crassus.

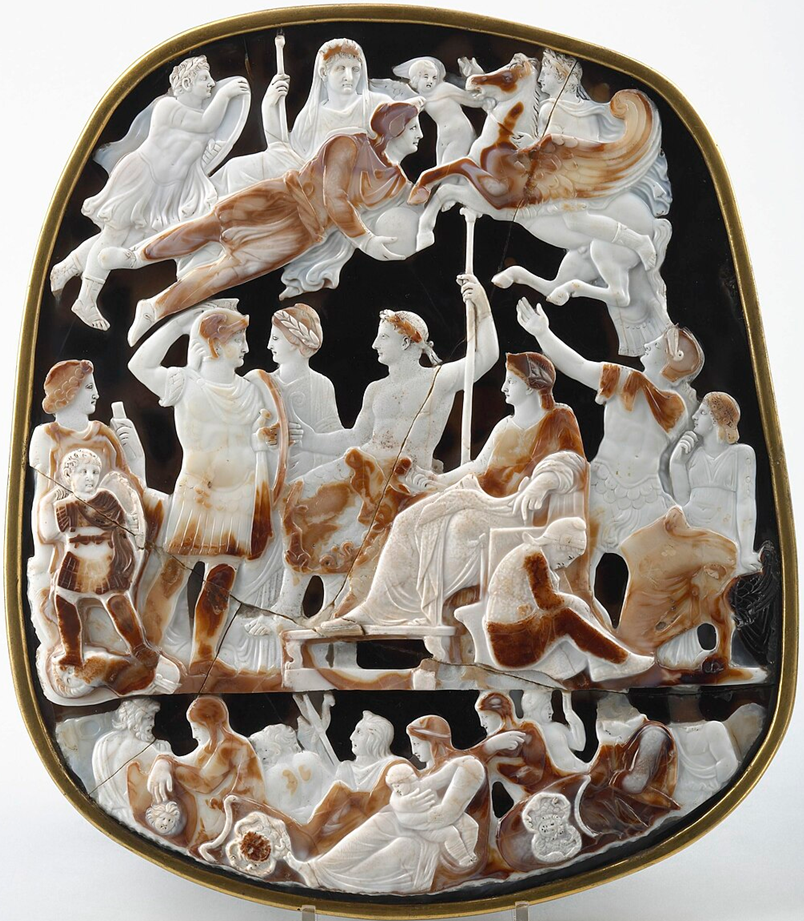

Augustus took a different tack: diplomacy. Suetonius tells us a (surely embellished) tale of the Parthians “pleading for [Augustus’] friendship” and “when he demanded the surrender of the eagles captured from Marcus Crassus and Mark Antony, not only returned them but offered hostages into the bargain; and once, because several rival princes were claiming the Parthian throne, they announced that they would elect whichever candidate he chose.” [3]

With the Parthian court in evident chaos, Augustus assumed a position of advantage over the Parthians which previous Roman leaders never enjoyed. He provided something of a resolution to the conflict between Parthian King Phraates IV and the usurper Tiridates II in exchange for the lost eagles and (presumably) assurances that Rome’s legions would not march to Ctesiphon to install the latter on the Parthian throne. Augustus retained Tiridates as a member of his household, and Romano-Parthian relations would remain mostly peaceful for over a century.

The Augustan doctrine was not, however, immune to overreach. The Great Illyrian Revolt (AD 6–9) jeopardized lands in the Balkans that were thought to have been recently tamed, and enabled Rome’s barbarian enemies to approach Italy before their ultimate defeat. But it was Germania that delivered the greatest blows to the Augustan doctrine. The destruction of three legions and 20,000 men in the Teutoburg Wald in 9 AD was the tragic culmination to years of campaigning in the German hinterland. These lands would never truly come under Roman sway. However, this disaster did perhaps instigate a change in Roman strategy that would guide the reign of the next emperor.

Tiberian Restraint

In his recent volume on Tiberian foreign policy,[4] applied historian and international relations scholar Iskander Rehman explores the emperor Tiberius purely with respect to his practical foreign policy, without paying attention to gossip from hostile sources. Rehman makes the case that Tiberius was, for all his personal defects, a prudent pilot of the Roman ship of state when its power was at its seeming height. His strategy, Rehman argues, would play “a critical role in ensuring the political continuity of the Principate, preventing the resurgence of civil war, and in averting potentially ruinous geopolitical overextension.”[5]

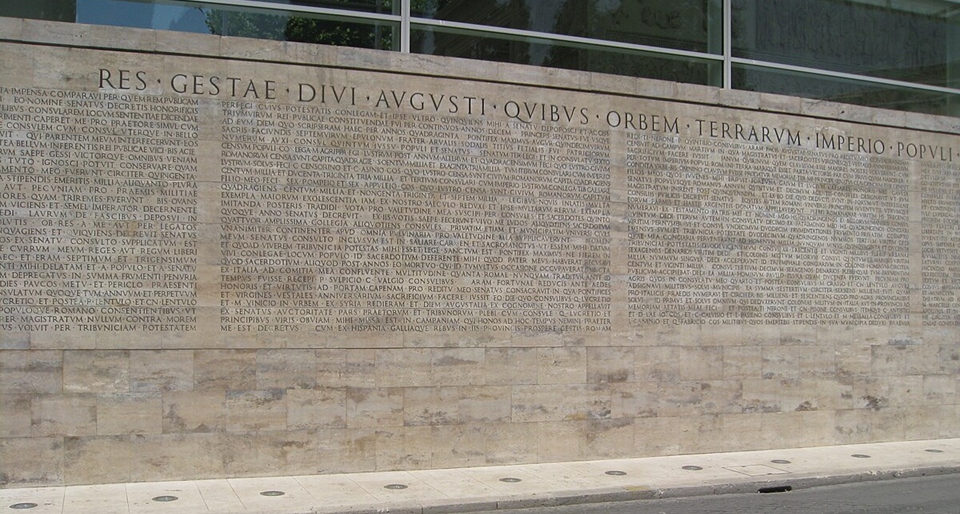

Shortly before his death in AD 14, Augustus left a series of official documents to be read before the Senate, the most famous of which is perhaps his “political testament”. As noted in Tacitus’ Annals (and later echoed by Suetonius and Cassius Dio), Augustus included “a clause advising that the empire should not be extended beyond its present frontiers. Either he feared dangers ahead, or he was jealous.”[6] The former appears more likely, but regardless Augustus’ consilium to his successors was a stark deviation from Roman policy practiced unreservedly heretofore. Rehman and Josiah Ober cast significant doubt on the authenticity of the political testament itself: the sources are, after all, highly inconsistent.

However, there is no doubt that Tiberius and many of his successors adhered, after a fashion, to Augustus’ injunction to freeze Rome’s boundaries. Indeed, Ober entertains the possibility that Tiberius himself was its true author:

If Tiberius did invent the Augustan consilium against expansion, the view of him as a faithful imitator of all Augustus; policies must be reexamined. Tiberius was a strong-minded individual; once we have dispensed with the notion of the political testament it appears that he had his own ideas about the empire and did his best to implement them. The political situation at the time of his accession forced Tiberius to make it seem that he was adhering to Augustan advice and precedent, a strategy that masked the fact that his foreign policy was actually very different from his predecessor.[7]

And so it was. While the reign of Tiberius (14–37) was marked by political intrigues, scandals, and despotism, it saw no major wars that were prosecuted for conquest. In Germania, Tiberius abandoned hope of maintaining a Roman presence east of the Rhine. Instead he exacerbated divisions between erstwhile Germanic allies and forewent large-scale Roman force commitments in favor of proxies. Through what Rehman calls “a combination of masterly inactivity and shrewd proxy management” there were no Teutoburg-style disasters during Tiberius’ reign.[8]

In the east, Tiberius did seem to follow the Augustan precedent, negotiating his way to an accommodation with the Parthians when their meddling in Armenia, then a Roman client state, threatened Tiberius’ interests there. There were no repeats of the Battle of Carrhae during his reign either.

Tiberius’ rule did see Rome’s frontiers expand somewhat. “As emperor,” says Ober, “Tiberius never intentionally initiated a major war of conquest, but he could conveniently forget the consilium against expansion when it suited his purposes. Cappadocia, Commagene, Trachonitis, and Gaulanitis were quietly and peacefully integrated into the empire during his reign.”[9] According to Rehman, this was an opportunistic rather than a purely acquisitive doctrine wherein “Tiberius seems to have run careful cost-benefit analyses, and eschewed undifferentiated expansion.”[10]

By the end of his reign, Tiberius was loathed by his people. Unlike his great predecessor, he was never deified. Yet his grand strategy injected a strong dose of prudence into Roman foreign affairs. As the empires of today tussle, territorial expansion and imperialism have reemerged within the strategic dialectic. Still, there seems to be no Tiberius in sight – for good or for ill.

Scott Strgacich is a research associate at Defense Priorities, a foreign policy think tank based in Washington, DC. His research focuses on nuclear deterrence, defense analysis, and the applied history of grand strategy.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Suetonius, Divus Augustus 21: nec ulli genti sine iustis et necessariis causis bellum intulit tantumque afuit a cupiditate quoquo modo imperium uel bellicam gloriam augendi, ut quorundam barbarorum principes in aede Martis Vltoris iurare coegerit mansuros se in fide ac pace quam peterent. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Henrik Mouritsen, Politics in the Roman Republic, (Cambridge UP, 2017) 129. |

| ⇧3 | Suetonius, Divus Augustus 21: ad amicitiam suam… petendam… signa militaria, quae M. Crasso et M. Antonio ademerant, reposcenti reddiderunt obsidesque insuper obtulerunt, denique pluribus quondam de regno concertantibus, non nisi ab ipso electum probaverunt. |

| ⇧4 | Iskander Rehman, Iron Imperator: Roman Grand Strategy under Tiberius (Bokforlaget Stolpe, Stockholm, 2024). |

| ⇧5 | Ibid., 137. |

| ⇧6 | Tacitus, Annales 1.11: addiderat… consilium coercendi intra terminos imperii, incertum metu an per invidiam. Tacitus claims this clause was included in Augustus’ breviary of imperial revenues and military dispositions, not in a “political testament” per se. |

| ⇧7 | Josiah Ober, “Tiberius and the Political Testament of Augustus,” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 31 (1982) 328. |

| ⇧8 | Rehman (as n.4) 127. |

| ⇧9 | Ober (as n.7) 328. |

| ⇧10 | Rehman (as n.4) 134. |