Jan Parker

The return of the hero from an identity-defining and potentially identity-denuding great war is a timeless literary topic: there was a lost poem in the Trojan War epic cycle called ‘The Returns’ of the Heroes (Nostoi); Pat Barker’s The Voyage Home has been shortlisted for the 2025 Anglo-Hellenic League Runciman Award. Uberto Pasolini’s film, a version of Homer’s Odyssey Books 13–24, is “the story of the mythical Greek hero, Odysseus (Fiennes) who, after 20 years away, washes up on the shores of Ithaca, haggard and unrecognisable.”

The film uses many of the dramatic scenes of the Odyssey’s latter half, smoothing them into a developing narrative of a withdrawn veteran who has seen too much blood. But in so doing, it is difficult not to think that it evades or glides beautifully past the very problems of “The Return” – of the hero – that make the Odyssey both psychologically realistic and profoundly thought-provoking.

Fiennes/Odysseus as “unrecognisable”: the second half of the Odyssey is centrally concerned with recognition. What of the Odysseus who went away is recognisable to those he left behind? And for what, as what, can he be recognised? This is a question for all in – and indeed outside – the story: a problem for soldiers and soldiers’ families though the ages faced with the returning veteran. Indeed, the psychiatrist first diagnosing PTSD in returning Vietnam veterans, Professor Jonathan Shay, in his Odysseus in America: The Trials of Homecoming drew on Homer’s account to compare the experiences of veterans and their families.[1]

For Odysseus, like some of those volunteers and conscripts, is not the young man going to fight in the war of wars, the war in which to gain “an immortal reputation”; nor is he a returning warrior hero like Ajax or Agamemnon. Rather, he was – ten years ago now – the man who thought of the cunning (unheroic?) trick to beat the Trojans: the Trojan Horse. He is a man whose return journey has been long and challenging.

Fiennes says that he reads his character Odysseus as “emptied out” by bloodguilt – so much blood at Troy, so many victims – that he is now a “no-man” (the name he gave himself to trick the Cyclops, now come true?). And veterans’ accounts, gathered under Shay’s diagnostic categories of “emotional coldness” and “social mistrust”, can be used to build a character such as Fiennes so tellingly plays.

But… how can we call Odysseus such a veteran? It is a very long time since he was fighting at Troy; and although the opening line of the Odyssey asks the Muse to tell the bard/tell us of this polytropos (many ways, many turns) man, we hear, rather, the delightful stories that Odysseus has crafted. For, in that long time since Troy, he has gathered the material that everywhere earns the bard welcome: the wondrous stories he has told of his travels thus far – among nymphs, goddesses, Sirens; taking on the Cyclops, Circe, the Lotus Eaters, Scylla and Charybdis – to his last host. He always has a rich tale to tell. But these stories don’t address, and indeed deflect from, the question he was asked by this host, asked by Greeks then and now, as well as psychiatrists: tis pothen eis, “who are you and, where from?” A precise question: who are you, really, and how do you account for how you have become that person?

This troubling question the film has already answered for its audience and itself: a battered, withdrawn veteran haunted by too much blood. But from the Odysseus who awakes, groaning, on the shore in Odyssey Book 13 to the victor over the suitors reunited with son and wife in Book 23, the question keeps being reframed, for us and seemingly for Odysseus himself. This “returned” Odysseus is unrecognisable also to Homer’s listeners, who have heard the spellbinding stories he wove in the Palace on Phaeacia, where, likewise washed up naked and battered on the shore, he was nevertheless able to woo and wow the royal family, and be lauded as a hero worthy of being the King’s son-in-law.

The film starts memorably with that naked, sea-wracked figure. Homer gives an equally memorable but different introduction to this Odysseus, who greets the, to him strange, land with his usual question – where am I? Are the people hostile or guest-respecting? The answers are given by a disguised Athena; Odysseus pre-empts any question of his identity: sea-battered and disorientated though he is, he immediately invents a rich persona with a comprehensive back story.

Fiennes called his character “emptied out” but, for Athena, he is more too glibly self-presenting than empty: polytropos as of many presentations. Too many adopted personas rather than just “of many ways”? Shay insists on the importance of helping soldiers to tell their stories. But the other key attribute ascribed to Odysseus is poikilomētis, “with a cunning mind that reflects variously”. Reflects variously: like a bard who gives the audience what they want rather than a truthful account of their experiences. Rather than emptied out, perhaps he, rather, is waiting to decide what story to tell, what identity to adopt? For, like Shay’s returning veterans’ “crisis of identity”, Odysseus must now decide how to present himself – who is he, now? And what narrative identity, what narrative of tis pothen – who is he and how did he become that – can he possibly tell? Athena, in wondering admiration, calls him polymētis, – canny, variously problem solving – saying:

“ἐπητής ἐσσι καὶ ἀγχίνοος καὶ ἐχέφρων.

ἀσπασίως γάρ κ᾽ ἄλλος ἀνὴρ ἀλαλήμενος ἐλθὼν

ἵετ᾽ ἐνὶ μεγάροις ἰδέειν παῖδάς τ᾽ ἄλοχόν τε·

σοὶ δ᾽ οὔ πω φίλον ἐστὶ δαήμεναι οὐδὲ πυθέσθαι,

πρίν γ᾽ ἔτι σῆς ἀλόχου πειρήσεαι.”

“You are always so plausible, so shrewd and so cautious! Any other man back from his wanderings would have rushed to his palace to see his wife and children, but you don’t care to ask or know a thing until you’ve tested your wife further.” (Od. 13.332–6)

Why doesn’t he do as “any other man”? is a startlingly realistic question about Odysseus’ psychology, which could be answered by a psychiatrist such as Shay treating war veterans as the returning soldier’s destroyed social trust, his new suspiciousness. But we who are being told the tale of Odysseus’ return have seen him in action many times before, negotiating with all kinds of environments, escaping all kinds of monstrous dangers and ensnaring voices.

But Athena tells him that he is back on Ithaca, good for goats, which will demand a double process of recognition: of the returning Odysseus being recognised and validated but also of Odysseus learning who he now is, in the non-Iliadic world of Ithaca. Non-Iliadic, non epic, non mythical world, with a hall, not the Knossos-type palace with storerooms, marble floors, luxurious and civilised culture he has come from: the suitors are eating the weaners and seedcorn that would allow survival into next year; the hall has a dirt floor for the scenes of after dinner entertainment of beggars fighting…

Indeed, the recognition and necessary adjustment to life on Ithaca goes not just for Odysseus – who doesn’t recognise the land – but also for us: as the film violently emphasises, this is an unfabulous, lawless and vicious Dark Age world, seemingly untethered from the structures of order and beauty that shape a good tale; where anything might happen.

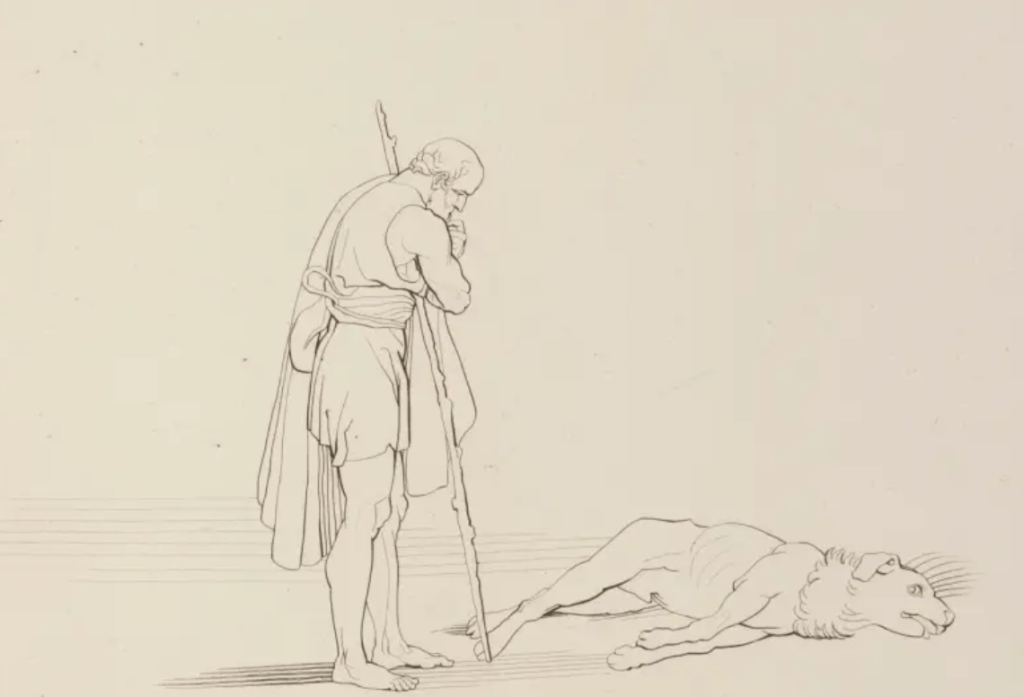

Only for his dog Argus, waiting these last twenty years for the master who trained him, recognition is simple; no words or explanation were needed: this Odysseus is “identical” to the one who went away, the relationship between master and hound unchanged by twenty years. For others, Odysseus has to establish himself, to be recognised not as anything but for what he now is. And, what is that?

The first half of the Odyssey is set after and against those waiting back home in limbo, having no idea where and as what he has been living: his son Telemachus, who has gone to Sparta to the Trojan War leader Menelaus to find out about the father he has never seen, and his wife Penelope, abandoned for twenty years.

And into that limbo come the central books of the Odyssey containing the enchanting stories Odysseus tells his final host, of his adventures among every kind of society, human, divine and monstrous. The question that hangs over Odysseus’ return is, when and how can he tell his (real) story? When and how can he have a narrative, not a fabulous, identity?

For most of Books 14–19 the question doesn’t arise: to faithful old Eumaeus, to his son Telemachus, and later in the Palace he ‘presents as’ a wandering beggar out to get whatever he can, with a shrewd eye to profit (a cloak from Eumaeus, food from the suitors). So, like a cunning Sherlock Holmes, he has a guise in which to present himself: battered, rough, on the lookout for titbits and handouts.

This raises a similar question to Athena’s: why does he not enter with a fanfare to say that he, the great Odysseus, is back and resuming his former roles of king and kurios (overlord/guardian) of the family? Is it because he now has been reduced to exactly how he appears: roughened, old, concerned with his goods, marginal? Perhaps he – like any soldier marked by his experiences – cannot ‘just’ reassume those roles, that identity. (Among many telling accounts of the problem of soldiers losing their identity see Patrick Hennessey’s autobiographical The Junior Officers’ Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars (Allen Lane, London, 2009).)

In The Return Fiennes portrayed a man who was emotionally numb; Shay talks of an

“emotional shutting down [in the returning soldier]. If the switch for the tender, softer, sweeter, more nuanced capacities for emotion remains jammed in the “off” position, then negotiating a life with a family, with a sweetheart or a wife, or with children becomes extraordinarily difficult.”[2]

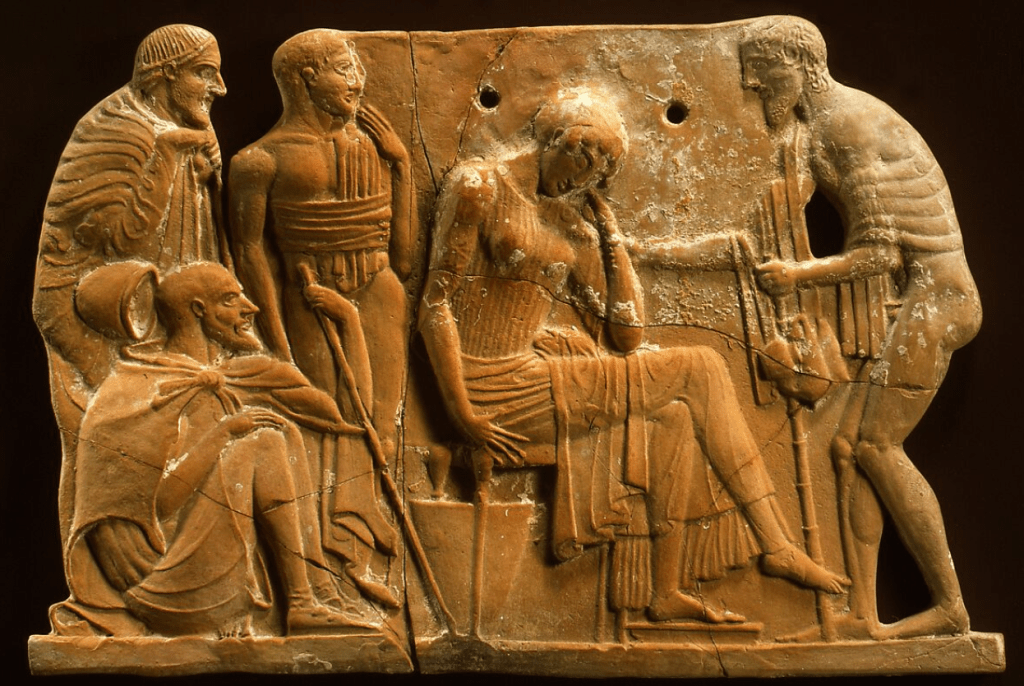

And the scene where Odysseus meets his son is particularly telling: the first sign of Telemachus’ return to the faithful swineherd is the fawning of Eumaeus’ dogs (they were ready to attack Odysseus when he arrived). Telemachus, unlike Odysseus, belongs here. Overjoyed, Eumaeus

ἀντίος ἦλθεν ἄνακτος,

κύσσε δέ μιν κεφαλήν τε καὶ ἄμφω φάεα καλὰ

χεῖράς τ᾽ ἀμφοτέρας: θαλερὸν δέ οἱ ἔκπεσε δάκρυ…

“ἦλθες, Τηλέμαχε, γλυκερὸν φάος. οὔ σ᾽ ἔτ᾽ ἐγώ γε

ὄψεσθαι ἐφάμην, ἐπεὶ ᾤχεο νηῒ Πύλονδε.

ἀλλ᾽ ἄγε νῦν εἴσελθε, φίλον τέκος, ὄφρα σε θυμῷ

τέρψομαι εἰσορόων νέον ἄλλοθεν ἔνδον ἐόντα.”

came to meet his master, kissed his forehead, his two sparkling eyes and both his hands, while the tears ran down his cheeks. “Telemachus, sweet light of my eyes, you are here! I thought I would never see you again, after you sailed away to Pylos. Come in, dear boy, and let me gladden my heart by gazing at you, home now from distant lands.” (Od. 16.14–16, 23–6)

Telemachus calls Eumaeus Atta, “Dad” – a respectful and intimate term. Similes in Homer are used frequently to point to an unusual yet striking similarity (Odysseus clinging to the rocky shore in Phaeacia like an octopus). But when Eumaeus greets Telemachus, Homer says:

ὡς δὲ πατὴρ ὃν παῖδα φίλα φρονέων ἀγαπάζῃ

ἐλθόντ᾽ ἐξ ἀπίης γαίης δεκάτῳ ἐνιαυτῷ,

μοῦνον τηλύγετον, τῷ ἔπ᾽ ἄλγεα πολλὰ μογήσῃ,

ὣς τότε Τηλέμαχον θεοειδέα δῖος ὑφορβὸς

πάντα κύσεν περιφύς, ὡς ἐκ θανάτοιο φυγόντα.

Just as a loving father greets a son returned from a far-off land after a nine-year absence, a dear and only son for whom he has suffered much pain, so did the noble swineherd embrace godlike Telemachus and kiss him endlessly as if he were back from the dead. (Od. 16.17–21)

The point of this simile is that it is a simile: Eumaeus is not Telemachus’ adoring father. The simile wonders at the gap between the emotions of the biological father – who demonstrates none of the natural sentiment of the simile and who observes his son coolly from the shadows – and the kind, tearful old man who has served as his emotional base all these years.

The recognition between father and son in both Homer and the film is abrupt. Odysseus says, “I am your father; you won’t get another.” Whatever the psychology being portrayed, this part of the story shows Odysseus trying to find his feet in a very real, unfabulous, world of Ithaca, where the dangers come from snarling dogs, lawlessness and a hall where axes can be hammered into the dirt floor of a residence that is very far from being a marble floored palace. What is it to be a hero in such a society? Odysseus the tricky-minded may have a multifaceted persona but in Homer there is a non-heroic continuity in his “disguised self”: he is recognisably “Odysseus the Crafty”, whether fighting a beggars’ duel, standing up to the suitors’ blows or begging his food with cunning stories. But is that an identity?

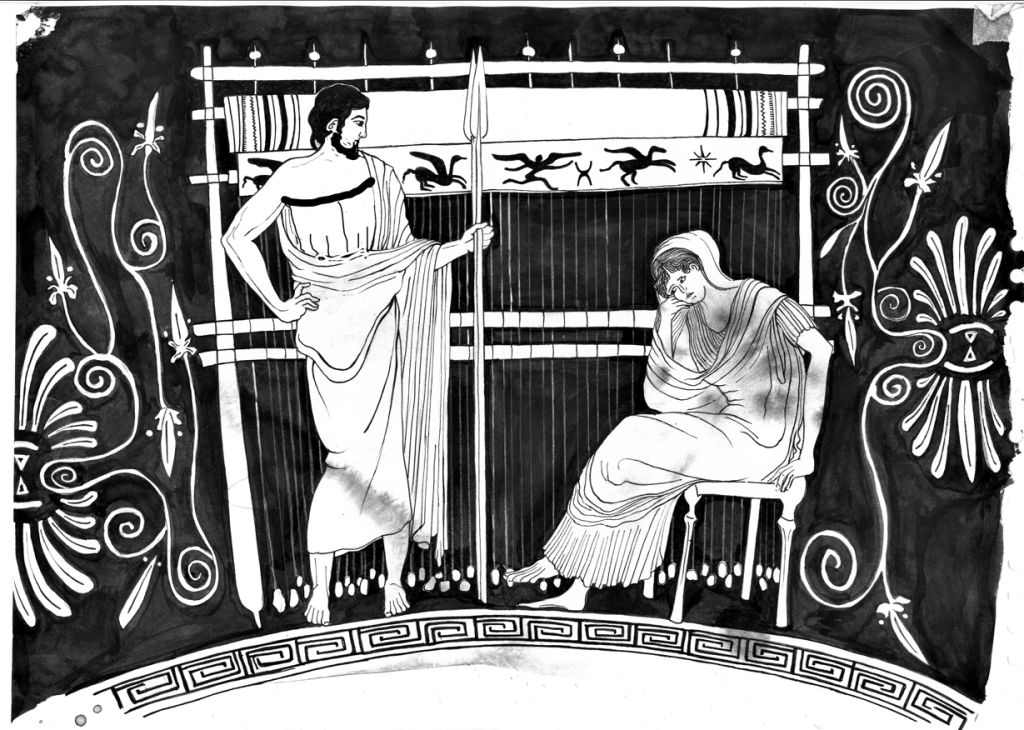

Meanwhile, through the narrative we glimpse a Penelope with a mind of her own who is keeping the suitors at bay and even going down to the hall to enjoy their gifts and attentions. Why should she just fall into his arms, when she could plausibly be thinking “any other man wouldn’t have taken ten years to wander before coming back?” (Margaret Atwood built on feminist critics – and indeed Homer! – to renarrate the Return from Penelope’s view point: The Penelopiad)

She has come up with a cunning strategy to keep the suitors at bay: she set up her loom to weave a shroud for her elderly father-in-law, Laertes, as is proper if she is to become part of a new family. But each night she unpicks the day’s work: a ruse that the tricksy Odysseus – polymēchanos, “of many devices” – surely appreciates. However, one of the maidservants has caught her unravelling the weaving, so now she is forced into facing up to moving on: her son is now of age and is capable of becoming the lord of the land and household. Odysseus’ return coincides with and precipitates the new independence of both his son and wife: Penelope’s reaction both to her son’s maturity and to the now more authoritative reports of Odysseus’ safety is beautifully described. Among these is the easily recognisable scene of a prompt to Penelope that after years of waiting and mourning she should now show herself to the suitors in order to demonstrate her desirability to them… and herself.

Penelope says several times that Odysseus took with him her bloom and value as a woman. Here she says again that her “excellence” – she uses a term that a warrior would use of his fighting skill – was destroyed when Odysseus sailed away; if only he would come back to her, her reputation would be re-established and be greater than ever. With Odysseus listening, although she does not know that, she is using heroic terms. As a man demonstrates his aretē in contest, in battle, in the assembly and by the prizes he accrues, so a woman demonstrates hers by the dowry she can command and by the gifts she can inspire.

When Penelope and Odysseus-as-stranger finally come together, their exchanges are in character but strike common resonances. There is a sense of recognition, not of Odysseus’ identity but of some kind of like-mindedness.

The stage is set for a thrilling scene of denouement and reunion: Penelope springs into action, acknowledging her son’s coming of age as a rite of passage for her too: she offers to marry but demands proper wooing gifts. (Odysseus in disguise said he had seen Odysseus’ stockpile of rich gifts amassed on the way home: “he would have been home long before, but has travelled to accrue wealth.” As a proper suitor, he has been amassing gifts to bring to a marriage games.)

But, when Penelope turns to Odysseus and asks him for his story, he responds with another ‘Cretan tale’, inventing a lineage and home, where he says he hosted Odysseus: “He spoke false just like true” – the storyteller who can make deceiving fiction affect the listener as if real. Tears run down Penelope’s cheeks as she listens.

Odysseus’ emotional detachment has been thrown into relief by Eumaeus’ deeply felt and expressed bond with Odysseus’ son and with the mother for whose death he, rather than Odysseus, grieved for; and now by the narrative of distrust, justified perhaps by the age-old stories about unfaithful wives (Agamemnon’s return to a scheming and murderous Clytemnestra) that play around the fringes of this Return story.

And Penelope has her own caution and testing mechanisms. Deeply affected though she is, she stops her tears and tests him: what was Odysseus wearing? Odysseus can of course answer this perfectly, describing the fine clothes and unusual cloak pin he was wearing when he left – thus passing the test as is proper but also cementing Penelope’s image of the Odysseus that used to be. He swears that Odysseus is on his way home, which, although Penelope will not accept it as proof of his survival, has established a perhaps deeply problematic link between Odysseus as was and this battered man in front of her.

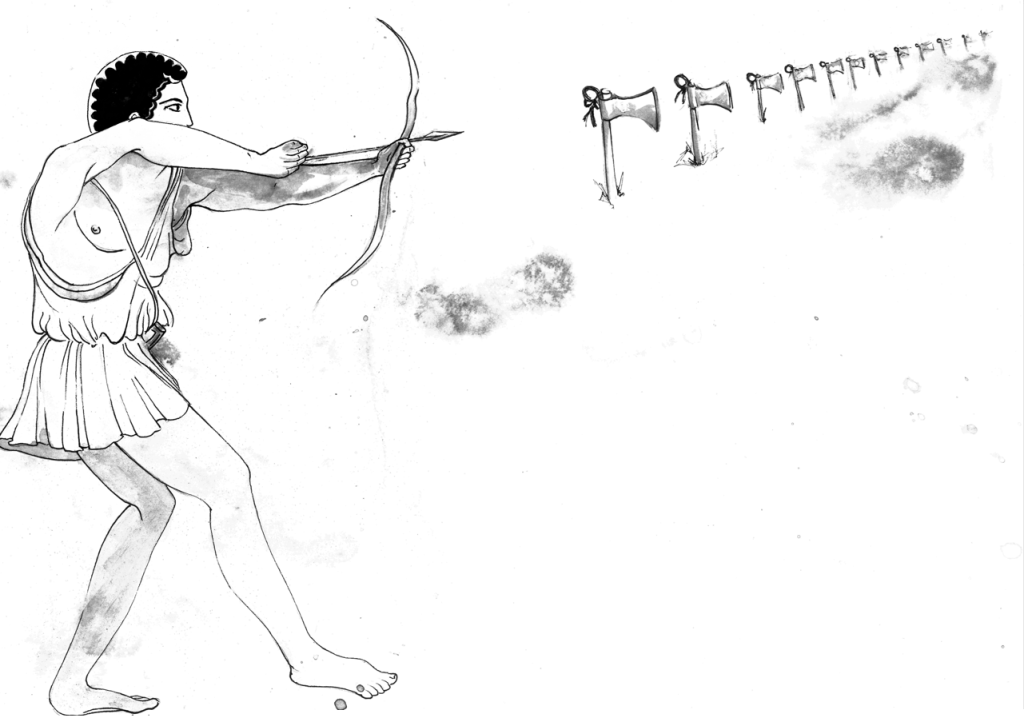

This is a beautifully scripted account of the narrowing of the gap, the gradual coming together, of two long-parted spouses, whose lives have diverged so radically, but also of Odysseus as was and Odysseus as he is now. A novel could carry through the famous denouement: Penelope orders a ‘marriage game’. Anyone seeking to supersede Odysseus has to be able to string his bow and pass the final test: to shoot the arrow through twelve axes. Of course, the still disguised Odysseus steps forward when the suitors all fail: he has rewon the bride, and can carry her off to the special bedchamber – a bed built out of a living tree.

But Homer weaves a dark thread through this ‘recognition’ and ‘return’ narrative. Whereas the old dog Argus’ recognition of his master was moving and unthreatening, there is a different conclusion to a recognition of Odysseus by his old nurse: his response to her recognising a boyhood scar on his leg is, shockingly, to threaten her with violence.

Even more starkly, following her long talk with the disguised Odysseus, Penelope had had a revealing dreams of his return: that she was feeding her pet geese when an eagle came and killed them all. While she was grieving over the bedraggled corpses, the eagle spoke in a man’s voice, saying that he was Odysseus and would return and wreak vengeance on the suitors.

The still disguised Odysseus cannot see a problem with the interpretation: it is a portent that Odysseus would return and kill the suitors! But Penelope introduced the dream saying that her grief was like that of a mother turned into a nightingale after accidentally killing her daughter; the suitors are her pets, all of them killed by a huge-taloned eagle in the guise of Odysseus. And seemingly, that is what has happened to the Return narratives: the stringing of the bow, the reunion in the fabled marriage bed (which Penelope asks him to move; a final test which enrages Odysseus) – both ‘fable’ endings – turn violent.

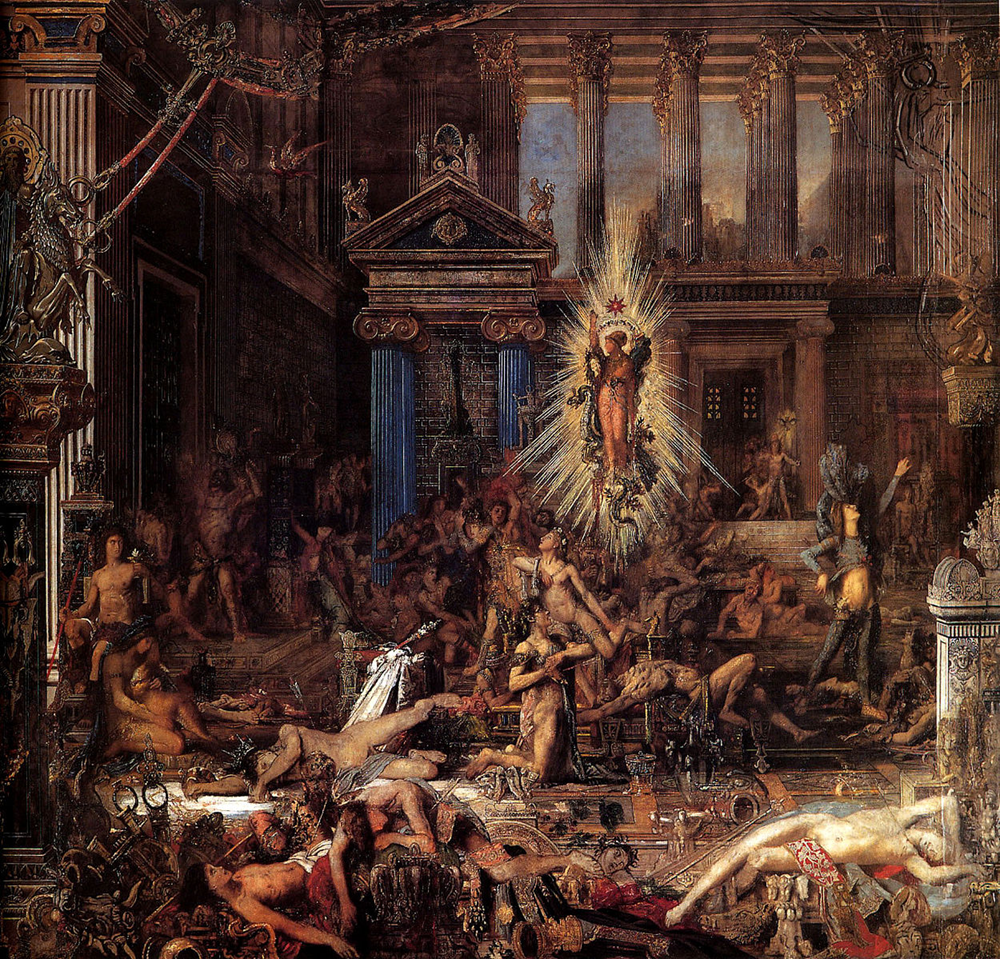

The killing of the suitors is graphic in the extreme: the setting up of the Dark Age axes is followed by dark vengeance, with a certain bloodthirstiness that, despite its battlefield setting, is less a feature of the Iliad. Odysseus and the others attack them like vultures whose crooked talons and curving beaks swoop down from the mountains on smaller birds that try but fail to get away; all the rest are killed like fish caught in a net. Odysseus “is drenched in blood from head to foot, like a lion feeding on an ox, up to his haunches in gore.”

And then the punishment of ‘collaborators’: a goatherd Melanthius is horribly and graphically tortured and mutilated for the role he has played. But, even more disturbingly, the vengeance is carried on to the twelve maidservants who have been “consorting” with the suitors. They are made to clean up the slaughter in the hall, then led out and killed by being strung up by the neck on a cable, their feet not touching the ground, “like long-winged thrushes or doves caught in a snare as they go to roost in their thicket.”

They writhe for a while in the noose, but their feet soon stop kicking. After Penelope’s dream, of Odysseus as a cruel eagle killing her pets, this image of gratuitous violence on female servants who have been “polluted” – no indication that they were willing – and have to be destroyed is meant to trouble.

But most troubling is the narrative not of joyous reunion but of the continuous testing and testiness of the returned Odysseus: when he finally goes to his father Laertes, who is “dressed in a wretched filthy patched tunic, old and worn and burdened with grief”:

μερμήριξε δ᾽ ἔπειτα κατὰ φρένα καὶ κατὰ θυμὸν

κύσσαι καὶ περιφῦναι ἑὸν πατέρ᾽, ἠδὲ ἕκαστα

εἰπεῖν, ὡς ἔλθοι καὶ ἵκοιτ᾽ ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν,

ἦ πρῶτ᾽ ἐξερέοιτο ἕκαστά τε πειρήσαιτο.

ὧδε δέ οἱ φρονέοντι δοάσσατο κέρδιον εἶναι,

πρῶτον κερτομίοις ἐπέεσσιν πειρηθῆναι.

Odysseus debated in heart and mind whether to clasp his father to him with kisses and tell him the whole story of his return home; or whether first to make trial of him with questions. On reflection he thought the latter was best, to try him first with testing words. (Od. 24.235–40)

The testing words which suggest that Odysseus is dead nearly kill the old man; but in reassurance Odysseus reveals himself and shows him a scar from his boyhood hunting trip with his grandfather…

Why? Return recognition tests, and proofs such as the scar, are traditional motifs in oral poetry through the ages. Pop psychology could suggest that Odysseus has not dealt with – certainly not acknowledged – the harm that has come to his father and mother through his prolonged absence. And both ancient myth and current psychology point to intergenerational conflict, between sons and fathers. Another traditional ‘return’ motif, as with Theseus, is that of the son testing to destruction his father? But that testing is of the young hero returning to supplant the old, not a testing of a barely surviving, grief-stricken father.

Jonathan Shay talks of the returning soldier’s destroyed social trust, his new suspiciousness: “Every interaction that person enters into is framed as, ‘I have to strike first.’ Or, ‘What’s your gain? How are you deceiving me by expressing these good intentions?’”

Fiennes portrayed a man who was emotionally numb; Homer a man who on Ithaca breaks into violence:

The soldier’s hypervigilance and aggression tend to transfer ‘back home’, can lead to an emotional shutting down. If the switch for the tender, softer, sweeter, more nuanced capacities for emotion remains jammed in the ‘off’ position, then negotiating a life with a family, with a sweetheart or a wife, or with children becomes extraordinarily difficult.”[3]

So, what kind of return is this? Return of the soldier? Well, perhaps. In the film, the final healing comes from the sharing of Odysseus’ memories: that will, as with Shay’s veterans’ sharing their trauma, “transmute the pain into something else: not relief, necessarily, or transcendence, and certainly not glory, but maybe a kind of understanding.” Homer has a similar understanding: as Eumaeus the swineherd says to the disguised Odysseus:

“κήδεσιν ἀλλήλων τερπώμεθα λευγαλέοισι,

μνωομένω· μετὰ γάρ τε καὶ ἄλγεσι τέρπεται ἀνήρ,

ὅς τις δὴ μάλα πολλὰ πάθῃ καὶ πόλλ᾽ ἐπαληθῇ.”

“Let us take delight in each other’s woes as we recall them: for even someone whjo has suffered greatly and wandered much later finds joy in pains.” (Od. 15.399–401)

Psychiatrists who treat returning soldiers say baldly that “narrative is central to recovery”. But Odysseus never does tell his own story: after he is reunited with Penelope, when they share – in his case much redacted – stories, he explains that he must go off again shortly. Unlike the film, unlike a romance or biography, there is no closure.

Jan Parker is a Senior Member of the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge, where she teaches, researches and writes on tragedy and epic. Her latest book, The Iliad and Odyssey: the Trojan War, Tragedy and Aftermath (Pen & Sword, Barnsley, 2021) is joined by her writings on trauma for The Polyphony: Conversations across the Medical Humanities (available here) and “Iliad, Ajax, Electra, and the clinical encounter: debating the “end” of life,” in Literature and Medicine 38.2 (2020) 375–98. As the Founder Editor-in-Chief of Arts and Humanities in HE, she edited the Special Issue in 2018: Representing Trauma; Honouring Broken Narratives (available here). Theoretically now retired, she divides her time between teaching in Cambridge and walking and singing in Whitby, North Yorkshire.

Notes

| ⇧1 | For an exploration of these themes in the case of the Emperor Tiberius, see this Antigone article by John Roth. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | See Shay’s “The Trauma of War” in A. Himes & J. Bultmann (edd.), Voices in Wartime Anthology (Whit Press, Seattle, WA, 2005) 51–61. |

| ⇧3 | Ibid., 53. |