Patrick Liu

The heroic figure is a timeless archetype, appearing across all cultures and mythologies. However, comparing the protagonists in classic works such as Homer’s Iliad, Virgil’s Aeneid, and the Chinese epic Journey to the West reveals heroes who are very different from one another – and in fundamental ways. In fact, they are so divergent in terms of their ideals, values, and struggles that it raises the question: if conceptions of heroism can be so wildly different that they are in some cases diametrically opposed, can there really be a universal human notion of “hero” that transcends given cultures? By analysing how the heroic ideal is portrayed in each of those disparate works, we will see whether a common thread nevertheless emerges.

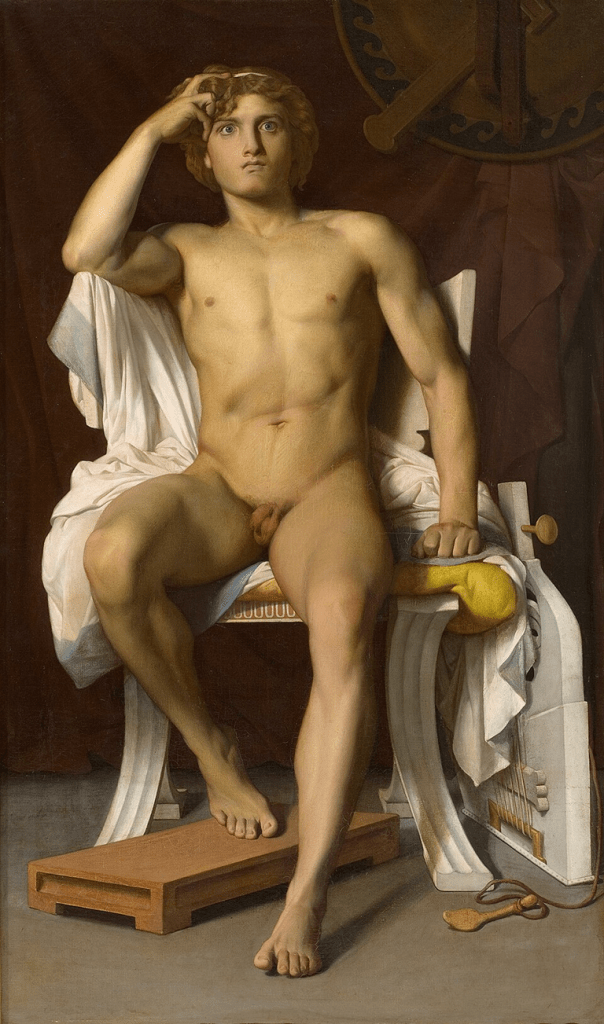

Achilles: Glory and Recognition

The Iliad begins with the famous invocation of Achilles’s anger, the proclaimed theme of the epic: “Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’s son Achilles and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians” (1.1: μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος |οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾽ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾽ ἔθηκε).[1]

Understanding Achilles’ anger and choices also helps us understand what defines him as a hero within the context of the Ancient Greek culture that spawned this epic. Initially, it might seem that Achilles’ anger stems only from a personal insult: Agamemnon’s seizure of Briseis, Achilles’s war prize. However, Briseis is more than that. She is a symbol of the honor and recognition accorded to Achilles for his achievements, and such a symbol carried great weight and importance within the Ancient Greek value system.

In the Iliad, heroic traits such as honor, bravery, and martial prowess are demonstrated in battle—“the fighting where men win glory” (7.113: μάχῃ ἔνι κυδιανείρῃ). That glory is given tangible representation in the form of women, slaves, and plunder. These prizes are not merely valuable in themselves but also for what they signify: heroic accomplishments.

Achilles explains, “Now the son of Atreus, powerful Agamemnon, has dishonored me, since he has taken away my prize and keeps it” (1.355–6: ἦ γάρ μ᾽ Ἀτρεΐδης εὐρὺ κρείων Ἀγαμέμνων | ἠτίμησεν: ἑλὼν γὰρ ἔχει γέρας αὐτὸς ἀπούρας). By taking Briseis, Agamemnon denies Achilles’ accomplishments, strips him of his hard-won glory, and thereby negates the entire heroic value system. This makes the act worse than just a personal insult, because that system is not a random set of rules, but something endorsed and embodied by the gods themselves.

We can see this in how even the gods must respect the strongest among them, Zeus, and in how they expect mortals to respect and honor them. If they are not properly honored through sacrifice, they become angry like Achilles, demanding the respect they deserve. Like Achilles, they may refuse to help those who fail to deliver that respect. For instance, when the Achaians construct a protective wall near the sea but fail to offer the gods a sacrifice, Poseidon takes offense. Meanwhile, Helenus implores Hector to honor Athena with “twelve heifers, yearlings, never broken, if only she will have pity on the town of Troy, and the Trojan wives, and their innocent children” (6.93–5: οἱ ὑποσχέσθαι δυοκαίδεκα βοῦς ἐνὶ νηῷ | ἤνις ἠκέστας ἱερευσέμεν, αἴ κ᾽ ἐλεήσῃ | ἄστύ τε καὶ Τρώων ἀλόχους καὶ νήπια τέκνα). For the gods, sacrifices are the equivalent of the heroic warriors’ prizes: a clear demonstration that they are being accorded appropriate respect.

The warriors emulate the gods by similarly demanding honor and respect, as well as by seeking to be immortal like the gods are, something they can only achieve through glory. In The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, the Classicist Gregory Nagy summarizes the ultimate aim of the Greek heroes as being to “reach a blissful state of immortalization after death”.[2] This is why Achilles tells Odysseus, “If I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans, my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting” (9.412: εἰ μέν κ᾽ αὖθι μένων Τρώων πόλιν ἀμφιμάχωμαι, | ὤλετο μέν μοι νόστος, ἀτὰρ κλέος ἄφθιτον ἔσται). Agamemnon, therefore, has not just broken a rule; he has defied divine law. Taking Briseis – the symbol of another man’s honor – violates this sacred code, offending both Achilles and the gods, which is why Zeus and Thetis are indignant and take Achilles’ side.

From a modern standpoint, it is easy to interpret Achilles’ one-man strike as selfish. While his decision does highlight the struggle for individual glory as a defining trait of the Homeric hero, Achilles’ refusal to fight is not just about prioritizing his personal pride and desire for glory over his comrades’ needs. He is also standing up for a principle. Refused the honor he has rightly earned, he sees no point in risking his life on the battlefield. After all, if fighting no longer offers glory, what is the point?

Worse, if the heroic value system can be ignored, then even glory means nothing. Agamemnon has pulled the rug out from Achilles’ entire understanding of what it means to be a hero. When the latter remarks, “We are all held in a single honor, the brave with the weaklings” (9.319: ἐν δὲ ἰῇ τιμῇ ἠμὲν κακὸς ἠδὲ καὶ ἐσθλός), he is contemplating the baffling reversal of all that he once took for granted. Later, his comrades hear him “singing of men’s fame” (9.189: ἄειδε δ᾽ ἄρα κλέα ἀνδρῶν), much like Nestor’s wistful recollection of the old days when heroic values were respected and meant something (1.260–1). Achilles essentially boycotts the Trojan War in order to draw attention to how Agamemnon’s unjust and dishonorable behavior threatens the entire system by which they have all been living their lives.

Aeneas: Duty and Destiny

Under the Ancient Greek value system, Achilles’ first priority is personal glory. Achieving glory is so important to him that he abandons his own comrades to fight without him. By contrast, other cultures have strongly associated heroism with duty and self-sacrifice. Ancient Rome was one such culture.

Aeneas, the protagonist of Virgil’s Aeneid, exemplifies the Roman virtue of pietas – a sense of duty that encompasses devotion to the gods, family, and the state. The concept of pietas was central to Roman ethics, as social harmony was seen as depending on citizens fulfilling their responsibilities to each other and to the gods.[3]

In the epic, Aeneas is referred to as pius (“duty-bound”) and calls himself that as well. One of his comrades declares that there are “none more just, none more devoted to duty” (1.544–5: quo iustior alter | nec pietate fuit)[4] and the narration calls him “devoted to his shipmates” (based on 1.220: praecipue pius Aeneas). That Aeneas is loyal to his comrades is beyond doubt, as the epic ends with him slaying Turnus, rejecting mercy specifically because he feels compelled to avenge Pallas (12.945–52).

Aeneas’ duty to his family is demonstrated even more intensely. During the fall of Troy, he carries his father, Anchises, on his shoulders, saying “This labor of love will never wear me down” (2.708: nec me labor iste gravabit). When his wife, Creusa, is lost in the chaos, he plunges back into the peril of the besieged city to find her, like a man running back into a burning house. And when Aeneas seems on the verge of despair and near abandoning his quest to found a new nation, Jupiter sways him not by promising glory but by telling him to think of the legacy and future he is leaving to his son: “If he will not shoulder the task for his own fame, does the father of Ascanius grudge his son the walls of Rome?” (4.233–4: nec super ipse sua molitur laude laborem,| Ascanione pater Romanas invidet arces). This also links Aeneas’ familial duty with his duty to the gods and the destiny they have promised for him.

For Achilles, winning glory in battle is an end in itself. For Aeneas, honoring the gods is more important. Aeneas is repeatedly referred to as “devout” and hailed as “famous for his devotion” (1.10: insignem pietate virum). He even suggests that battle has made him “unclean” and that he must be careful not to dishonor the gods by polluting their icons or rituals: “I, just back from the war and fresh from slaughter, I must not handle the holy things – it’s wrong – not till I cleanse myself in running springs” (2.718–20: me bello e tanto digressum et caede recenti | attrectare nefas, donec me flumine vivo | abluero).

The gods have set him on the path toward his destiny, and that of Rome. When Aeneas deviates from that path, Jupiter commands him to stay the course, reminding him that he will be “the one to master an Italy rife with leaders, shrill with the cries of war, to sire a people sprung from Teucer’s noble blood and bring the entire world beneath the rule of law.” (4.229–31: fore qui gravidam imperiis belloque frementem | Italiam regeret, genus alto a sanguine Teucri | proderet, ac totum sub leges mitteret orbem). Though unable to refuse this divine mandate, Aeneas muses about what different choices he might have made “If the Fates had left me free to live my life, to arrange my own affairs of my own free will” (4.341–2: me si fata meis paterentur ducere vitam | auspiciis et sponte mea componere curas).

The collision of duty and personal desire is most apparent and poignant in Aeneas’ decision to leave Dido despite their mutual love. His love for Dido conflicts with his divinely ordained fate. Dido bemoans the fact that Aeneas’ devotion to the gods takes precedence over his feelings for her, saying “Apollo the Prophet, Apollo’s Lycian oracles: they’re his masters now” (4.376–8: nunc augur Apollo, | nunc Lyciae sortes… fert… iussa). When she is dead, he admits as much, apologizing to her in the Underworld and saying it is the will of the gods that drives him. “Their decrees have forced me on” (6.462–3: cogunt… | imperiis egere suis). Though Dido “means the world to him” (4.291 optima Dido), the commands of Jupiter and his obligations to his family require Aeneas to “master the torment in his heart” (4.332: obnixus curam sub corde premebat). Therefore he tells Dido, “I set sail for Italy – all against my will” (4.361: Italiam non sponte sequor).

This moment encapsulates the nature of Aeneas’ heroism. Where Achilles chooses individual honor, Aeneas bears the weight of duty:

sed nullis ille movetur

fletibus aut voces ullas tractabilis audit:

fata obstant placidasque viri deus obstruit auris…

adsiduis hinc atque hinc vocibus heros

tunditur et magno persentit pectore curas;

mens immota manet, lacrimae volvuntur inanes.

But no tears move Aeneas now.

He is deaf to all appeals. He won’t relent.

The Fates bar the way

and heaven blocks his gentle, human ears…

buffeted left and right

by storms of appeals, he takes the full force

of love and suffering deep in his great heart.

His will stands unmoved. The falling tears are futile. (4.438–40, 447–9)

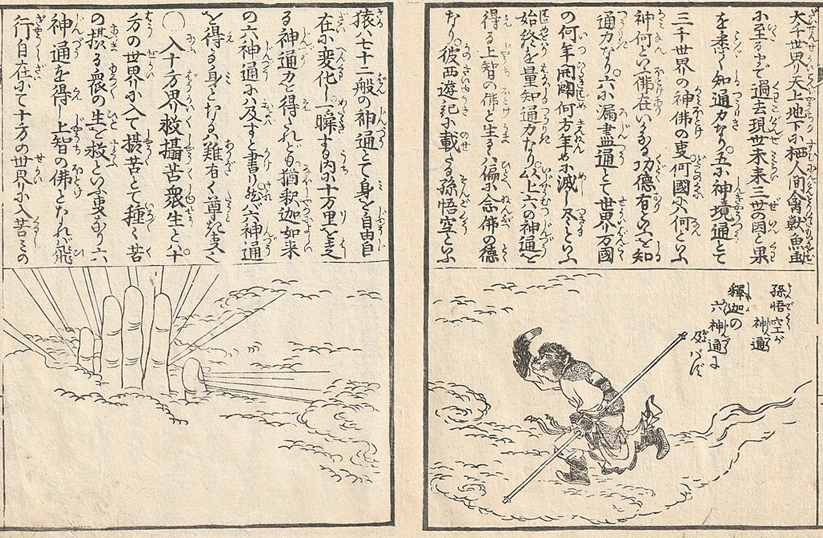

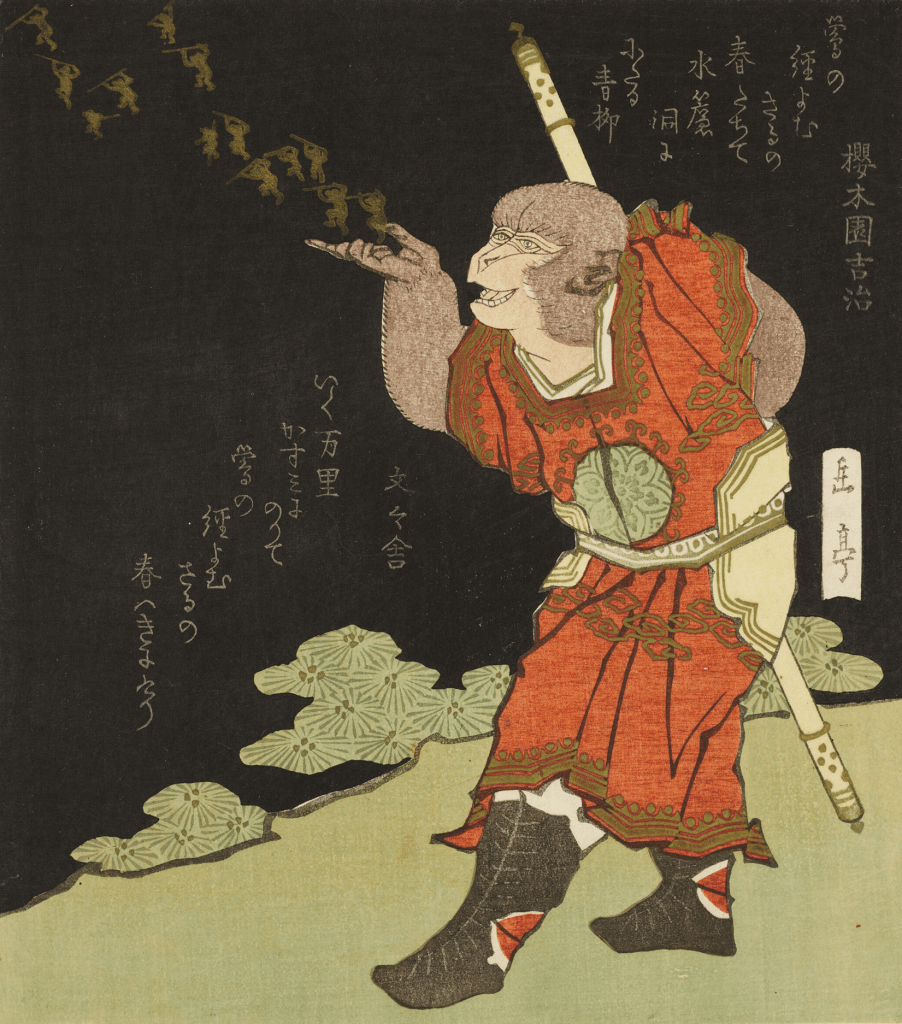

Sun Wukong: Wisdom and Enlightenment

In the Chinese epic Journey to the West, written in the 16th century, Sun Wukong – popularly known as the Monkey King – starts out very much like Achilles: he desires immortalityand glory. “If we die, shall we not have lived in vain, not being able to rank forever among the Heavenly beings?” he ponders (106:今日虽不归人王法律, 不惧禽兽威严, 将来年老血衰, 暗中有阎王老子管著, 一旦身亡, 可不枉生世界之中, 不得久注天人之内?).[5]

When he initially goes out seeking the Buddhas and holy sages, it is not for their wisdom but because he believes only they know how to “live as long as Heaven and Earth, the mountains and the streams” (107: 与天地山川齐寿). Invited to Heaven, he leaves in anger when assigned a low rank; like Achilles, he is angry at not receiving the recognition he feels he deserves.

Unlike Achilles, however, Sun Wukong does not personally embody the values underpinning the culture from which the epic springs. Instead, his slow transformation from glory-seeker to Buddha illustrates the Neo-Confucianist tenet of ridding the mind of selfish desires in order find a path to enlightenment and sagehood.[6] When he is recruited to help the monk Tripitaka obtain a set of Buddhist sutras, his journey literally becomes a quest for knowledge and wisdom.

He does not undertake that mission voluntarily. He is first imprisoned, and then kept in line with a magic headband, which Tripitaka can use to control him when he behaves in an undisciplined manner – a metaphor illustrating the need for a disciplined mind when seeking wisdom and enlightenment. Again, it is Sun Wukong’s experiences rather than his personal ethos that corresponds to medieval Chinese cultural values.

Su Wukong also acts out the Buddhist belief that suffering arises from ignorance, as we cling to and crave things that are illusory and impermanent.[7] The illusory nature of things is an insistently recurring theme in Journey to the West. Sun Wukong must repeatedly battle demons and creatures masquerading as human beings. During one encounter, Tripitaka is deceived by a cadaver demon in disguise, and is only saved because Sun Wukong sees through her deceptions. This suggests that Sun Wukong is gaining the capacity to see through illusion and grasp the fundamental nature of things, apparently even more than his master.

In another instance, Sun Wukong must literally battle himself – or what appears to be himself. During the contest, he appeals to the Bodhisattva Guanyin, “Please help your disciple to distinguish the true from the false, the real from the perverse.” (借菩萨慧眼, 与弟子认个真假, 辨明邪正) However, defeating this opponent is not merely another example of overcoming illusion; it is also a clear depiction of the inward journey toward wisdom and enlightenment as a struggle against one’s own self.

Through trials of discipline and patience, Sun Wukong learns that true heroism is not about power or glory but about wisdom. Seeking wisdom is ultimately what defines heroism in Journey to the West. While Achilles defeats Hector and takes revenge for the death of Patroclus, and Aeneas secures Rome’s future, Sun Wukong’s story concludes with spiritual transcendence, as he achieves enlightenment and is granted the title of “the Buddha Victorious in Strife”.

Unlike Achilles and Aeneas, Sun Wukong changes in fundamental ways in the course of his story. His motivations and behavior evolve. As a result, it is not Sun Wukong’s choices, but rather the overall path he follows, that defines heroism in Journey to the West. That path leads to internal transformation and self-improvement, goals that were as central to the Buddhist and Confucian values of medieval China as battlefield prowess was to the Greeks and sacred duty was to the Romans.

The Common Denominator: A Lesson in Values

While Achilles and Aeneas grapple with the cost of glory and duty, respectively, Sun Wukong’s journey is about mastering the self. This difference – between being a hero and following a heroic path – helps us to find commonality among these three very disparate stories and the visions of heroism they represent.

Embedded within their individual traditions, Achilles, Aeneas, and Sun Wukong probably would not have recognized one another as heroes, since their ideals, values, and struggles are so divergent. Yet we can acknowledge all three as heroes because, as illustrated above, their stories are all deeply invested in the values prized by their respective cultures, different as those values may be.

That divergence demonstrates that heroism is not universally about glory, or self-sacrifice, or attaining wisdom. Instead, we discover the commonality among these stories in the way that they reveal a higher order, and show us how to live in harmony with that order. Achilles, Aeneas, and Sun Wukong are role models, embodying the aspirations of their respective societies, whether by living out their culture’s highest values or just struggling to do so.

This makes them vivid cultural mirrors reflecting what those cultures considered noble, virtuous, and admirable – which is ultimately what all cultures ask for in a hero.

Patrick Liu is a high school student at The Dalton School in New York City. He studies Latin and Ancient Greek and has a particular interest in cross-cultural mythology and Greek poetry. He spent the last summer studying Ancient Greek intensively at the CUNY Latin/Greek Institute and is a peer Latin tutor and the leader of Dalton’s Classics club. He is currently exploring the cultural, philosophical, and literary connections between Chinese civilization and the ancient Mediterranean world.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Iliad citations are taken from Richmond Lattimore, The Iliad of Homer (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1951). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Gregory Nagy, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2020) 258. |

| ⇧3 | See further, e.g., Danyang Zheng, “The memetic connotations and evolution of ‘Pietas’ in Roman ideology, ethics and politics,” SHS Web of Conferences 183 (2024). |

| ⇧4 | Aeneid citations are drawn from Robert Fagles, The Aeneid (Penguin, London, 2006). |

| ⇧5 | Journey to the West citations are drawn from Anthony C. Yu, The Journey to the West (Chicago UP, 2012). |

| ⇧6 | Fung Yu-Lan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy (Macmillan, London, 1958) 272. |

| ⇧7 | Ibid., 244. |