Spencer Klavan

“Even if God exists, why should he care about me?”

This is an old and powerful argument against religious belief. Its poster boy is Epicurus (341–270 BC), founder of the Hellenistic Era’s most alluringly provocative counterculture. As I explain in my new introduction to the subject, Epicureanism grew out of a belief that the world was made of atoms flowing and colliding in a limitless void. It was (disappointingly) not the invitation to horny debauchery that has become associated with its name. But it was a shot across the bow of the Socratic tradition, which agreed with conventional wisdom, at least insofar as it tended to view human life in the context of a divinely governed universe.

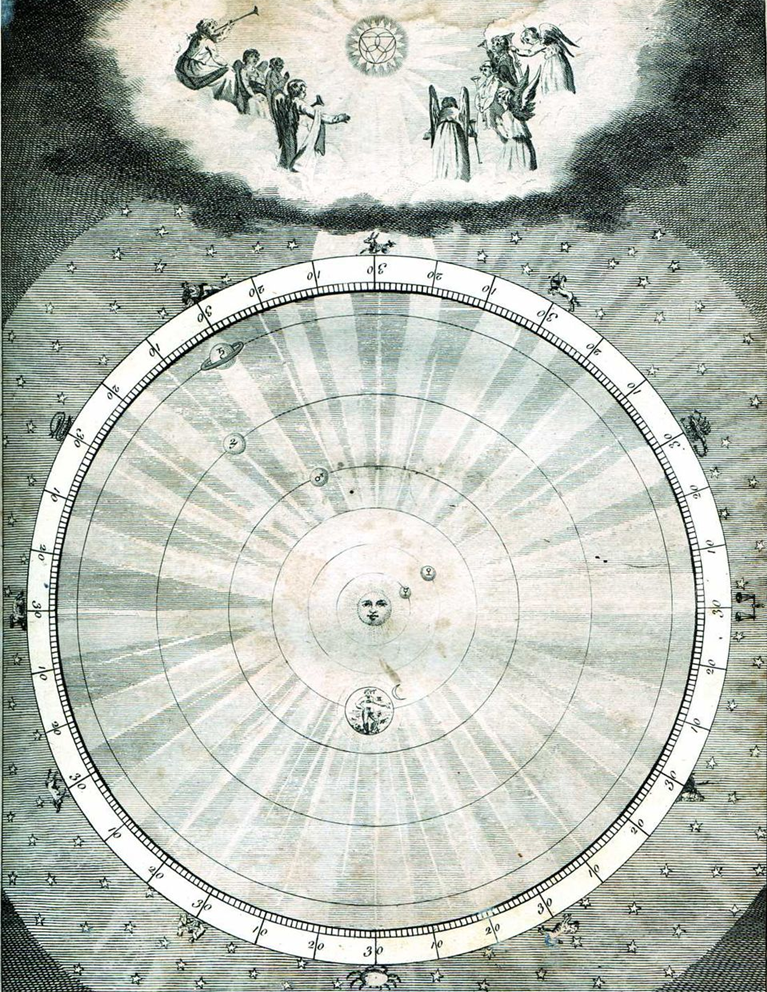

Stoics and Platonists alike thought that logos, rational order, could connect human choice to cosmic law. Cosmic law, in turn, applied to human action, which meant that the intelligence governing the universe was attentive to the difference between right and wrong, even in the relatively small realm of mortal individuals. Whatever their many and serious differences, most ancient moralists tended to assert that our choices can either harmonize or clash with the music of the celestial spheres.

Epicurus dispensed with all that. His argument, though incalculably less sexy than the sordid caricature of his thought put forward by his detractors, was no less scandalous. It wasn’t an argument for atheism, exactly, although it would certainly give ammunition to later atheists. Epicurus himself, in a letter to his student Menoeceus, was happy to concede that “gods exist, and our knowledge of that fact is manifestly clear — but they are nothing like what most people think of them.”

The trouble was not with belief in deities but with the absurd presumption that such deities would ever give a moment’s thought to mortals. “These assertions that people make about the gods are not innate convictions but inaccurate assumptions, which teach them that the gods do harm to bad men and reward good men” (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers 10.123–4).

What kind of trans-dimensional hyper-intelligence would deign to concern itself with mere human concerns like ‘right’ and ‘wrong’? How could the fleeting life of a puny swamp creature such as man ever interest the gods or disturb the perfect tranquility we must ascribe to them? Lucretius (c.94–55 BC), presenting Epicurean arguments in verse form to the smart set of late-Republican Rome, added that the gods probably couldn’t arrest the natural course of things even if they wanted to.

Consider the laws of physics, writes Lucretius in Book 2 of his poem De rerum natura, and natura videtur / libera continuo, dominis privata superbis, / ipsa sua per se sponte omnia dis agere expers (“and nature will reveal herself to you / Exactly as she is: unfettered. Free. / She has no overbearing lords; alone, / Spontaneous, she does the things she does. / She knows no gods” (1090-2). He adds that if gods really were meddling to contrive justice in human affairs, the results would be so mixed as to suggest a monstrous kind of ineptitude:

nam pro sancta deum tranquilla pectora pace

quae placidum degunt aevom vitamque serenam,

quis regere immensi summam, quis habere profundi

indu manu validas potis est moderanter habenas,

quis pariter caelos omnis convertere et omnis

ignibus aetheriis terras suffire feracis,

omnibus inve locis esse omni tempore praesto,

nubibus ut tenebras faciat caelique serena

concutiat sonitu, tum fulmina mittat et aedis

saepe suas disturbet et in deserta recedens

saeviat exercens telum, quod saepe nocentes

praeterit exanimatque indignos inque merentes? (2.1093–1104)

For – by the gods themselves,

Who live eternal lives of peaceful bliss

With quiet hearts of pure serenity –

What god could rule the vastness of all things?

Whose hand is firm enough to hold the reins

And keep them steady, tame the endless deep?

Who could compass all the sky at once

And roll its spheres, while also stoking flames

From purest air to scour the whole earth?

Who can be everywhere at every time,

Shading the sky with clouds and shattering

Its silences with thunder, sending bolts

Of lightning down upon his own stone shrines,

Or else retreating to the desert wastes

For savage target practice, managing

To miss the mark and strike the innocent?

This was the argument that David Hume (1711–76), channeling Epicurus twenty centuries later, advanced against divine providence in the daring eleventh chapter of his Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1748). To anyone who might claim “that the justice of the gods, at present, exerts itself in part, but not in its full extent,” Hume’s Epicurus answers “that you have no reason to give it any particular extent, but only so far as you see it, at present, exert itself” – which is to say, not very far (§109).

Epicurus’ 4th-century BC doubts take on added force in Hume’s 18th-century book. The intervening years brought with them the Copernican and Newtonian revolutions, flinging the boundaries of the universe far wider than they were previously thought to reach and casting humanity far from its imagined center. Epicureans had speculated that ours was just one among an infinite variety of possible and actual planets or even universes, occupying no particularly special location in the metakosmia, the sprawling world-scape. In early modernity it was starting to look, incredibly, as if Epicurus might have been right.

These were the conditions that could make resistance to godly intervention in human affairs seem plausible, even commonplace. When Stephen Hawking told an interviewer that “the human race is just a chemical scum on a moderate size planet, orbiting round a very average star in the outer suburb of one among a billion galaxies,” he was understood by many to be articulating the plainest good sense on the basis of the best scientific evidence.

There is even a cottage industry of self-help treatises designed to translate Hawking’s view into something like a modern serenity prayer. The argument goes that life in an indifferent universe ought to alleviate our existential unease and even our daily stresses. This is the message of “cosmic insignificance therapy”, an actual practice advertised by the motivational writer and speaker Oliver Burkeman as a way to alleviate the stress of even major life decisions. “I’m a tiny pinprick of consciousness on a modestly sized planet,” writes Burkeman on his website, “hurtling through infinite aeons across infinite space. Which is really relaxing, because it’s a reminder that in the grandest scheme of things, nothing I do or fail to do matters much at all.” So that’s reassuring.

Burkeman proposes that his approach has analogues in Stoic teaching, but he’s wrong about that. It is Epicurean, through and through. It even hearkens back to one of Epicurus’ favorite sources of inspiration: the early atomist Democritus (c.460–370 BC), who taught that consciousness itself is a bubble on the endless slipstream of atomic flow. This, he thought, should be conducive to euthymia, or cheerful serenity akin to that of the disinterested gods – a precursor to Epicurus’ ataraxia, the blissful unconcern that was supposed to result from abandoning all thought of death and the afterlife.

For Democritus, wrote the biographer Diogenes Laertius, “the goal of life is euthymia – which is not identical to pleasure, as some have mistakenly understood it, but is the state in which the soul proceeds peacefully and well settled, undisturbed by any fear, superstition, or other passion” (Lives of the Eminent Philosophers 9.45). Cosmic insignificance: it sets the mind at ease.

Or does it? Quite apart from the quasi-scientific assumptions entailed in this approach – which, as I have argued elsewhere, are seriously flawed – there is the question whether the prospect of cosmic insignificance is one we should welcome with a smile. True enough: if the universe really is just torrents of molecules and radiation surging through lightyear upon lightyear of cosmic ocean, then you can let yourself off the hook for the small stuff. Everything – relative to the timescales and magnitudes we talk about when we consider the heavens – is small stuff. But that does unfortunately mean everything: not just your seminar attendance but your marriage and family, your kid’s first birthday, your parents’ burial, your contributions to science or literature, your ancestry, your entire civilization, your species and your planet. Small, small, small.

This is the tricky double bind which traps adherents of Epicureanism and Cosmic Insignificance Therapy: if small things don’t matter, nothing does. There is no philosophically rigorous way to draw the line between things that are big enough to be consequential, and things that are not. Do cities matter, but not individuals? Do planets, but not countries? Quasars, but not quarks? Perhaps bigger things like countries matter more than smaller things like people. Granting that premise for the sake of argument, however, even a collective like a nation only matters so very much (if it does) because all the individuals in it matter at least a little. And however much moral worth we think those little lives have must add up to make the total loss we would suffer if, for instance, one of America’s many adversaries nuked it to bits tomorrow.

Moreover, at the level of our everyday experience we don’t even reason that way, adding up significance by measuring the relative size of things. Does a human child matter less than a large rock? How about a slightly shorter-than-average human adult? It’s only when the measurements involved are very large that it even occurs to us to think this way at all, as if physical magnitude had anything to do with significance. At a certain point the mind is so baffled by the effort to take in such volumes of space and time that we start talking punch-drunk nonsense about cosmic insignificance. The minute we bring the conversation back down to a manageable scale, we can see that it’s nonsense. The whole line of reasoning that looks for meaning in quantities is a dead end. Meaning, if it exists, must come from somewhere else.

Despite what we may profess to the contrary, most of us are moved by a powerful intuition that meaning does exist, at the level of the individual human life. The moral consequences of trying to suppress or explain away this basic intuition are exactly as monstrous and absurd as the physical consequences of trying to do a science experiment while doubting that valid observation is possible. If phrases like “moral worth” have any meaningful content at all then they must be built into the fabric of existence, not just coded as expedient fictions into our evolutionary programming. If so, then it starts to seem eerily possible that our sense of right and wrong is in fact reflective, however distantly, of a logos that governs the whole universe.

We have no less reason to believe this now that we know so much more about the laws of physics than Aristotle did. Actually the very fact that there are laws of physics at all counts as further indication that the structure of our thoughts bears some relation to the structure of the cosmos. If Einstein can have an idea down on earth, in his office, that allows him to predict the bend of starlight traveling past the sun, then at least some parts of our minds are structured not just in response to our local environment, but in conformity with the scaffolding of all things that reaches even to the farthest stars. Everything we say or could say depends on this one article of faith – the faith, as William James put it in “The Will to Believe”, “that there is a truth, and that our minds and it are made for each other.”

Similarly if life has worth and meaning, it has these not only once there is enough of it or once it endures for a certain length of time, or because we invented them to suit our immediate circumstances, but because worth and meaning are basic features of the universe that we see in it as surely as we see starlight. And if justice is present at some real structural level in the world outside of us, then what we are dealing with is a world that not only contains impersonal mathematical truths as features of its landscape, but also things like absolute good and evil. These by their very nature entail consciousness, will, and a quite fiercely active form of intelligence. Just about the only place we can locate things like math and morals is at a point of deep contact between human consciousness and the total architecture of the universe. A point of contact, that is, between the mind of man and the universal mind.

It may be that we are faced with two options: either God cares about everything we do, or no one has any reason to care about anything. In 1868, Alfred, Lord Tennyson imagined Lucretius chasing the Epicurean train of thought to its logical end with a shock of horror: “If all be atoms, how then should the Gods / Being atomic not be dissoluble?” (“Lucretius”, 114–15). The best answer to this nightmare dissolution of all things might be Wordsworth’s, in his 1807 ode “Intimations of Immortality”: “To me the meanest flower that blows can give / Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears” (202–3). Fashionable as the doctrine of cosmic insignificance has become since the scientific revolution, it has not actually become any more plausible. We have just as much reason as ever, in this vastly sprawling universe, to believe in the significance of small things.

Spencer Klavan is host of the Young Heretics podcast, associate editor of the Claremont Review of Books, and author, most recently, of Light of the Mind, Light of the World: Illuminating Science through Faith. He has published a monograph on Ancient Greek music, and has previously written for Antigone about Diogenes Laertius. He blogs on Substack here.