Nicholas Romanos

In November 2024, the Oxford Ancient Languages Society staged an ambitious dramatic recreation of Euripides’ Orestes, with a full score of music written according to what is known of Euripidean music. For an introduction to the OALS production, see this piece, and for an associated discussion of the interpretation of the play, see this piece. The present essay discusses the evidence for Euripides’ music, and how we went about composing a score for the lyric passages of the Orestes.

To set to music all the rich and complicated lyric passages of Euripides’ Orestes – all those lines which we know were originally sung on stage – is no small task. To write music that would not have sounded too far wrong to Euripides’ own audience of 408 BC is another matter entirely. That is the ideal that we (Nicholas Romanos and Beth Parker, the composers) aimed for in writing the score for this production; it is of course impossible to know what an Athenian theatregoer, or indeed the poet-composer himself, would have thought of our music, but we were able to draw on a significant body of ancient evidence regarding Euripidean music.

It was possible to make the first, and most crucial step, with some confidence. A distinctive impression is left on any piece of music by the structured series of pitches with which it constructs its melody: a fugue in our C Major scale sounds different from a piece in D Minor, and both are very different from the pentatonic scales used in other musical cultures. We are fortunate enough to know a good deal about Ancient Greek musical scales; and, though most texts describe a later system, the theorist Aristides Quintilianus (4th cent. AD?) has preserved for us a particularly ancient system of harmoniai (or ‘modes’), which are thought to date back to the 5th century BC.

These ‘modes’ are not scales in our modern sense, in that they do not repeat indefinitely in higher and lower octaves, but comprise a fixed set of notes, and imply a particular musical character, expression, and even vocal register. They are also all in the ‘enharmonic genus’ (N.B., this has nothing to do with the modern term ‘enharmonic’) – a version of the modes that we know to have been the most popular in the 5th century BC, and which notoriously makes use of ‘quarter tones’, i.e. tonal intervals smaller than those standardly used in most Western classical music.

Very excitingly, we have a papyrus fragment of the Orestes (written c.200 BC), containing ancient musical notation that indicates a melody for some of the words of the antistrophe of the play’s second choral ode (lines 338–43). The ancient notes preserved in this papyrus are perfectly consistent with both the (similar) Dorian and Phrygian modes of the ancient set described by Aristides.[1] This seems to justify the conclusion that Euripides – presuming the melody on the papyrus is his own[2] – composed his music in modes that were at least similar to the ancient harmoniai of Aristides.

Moreover, we can make a good guess at which of Aristides’ six modes Euripides’ would have used. Certainly this would have included the Dorian, which occupied a central place in Classical-era Greek music, was used in tragedy, and universally admired for its grand, manly character. (In fact, the Dorian was, along with the Phrygian, the only mode Plato did not banish from his ideal state.) The Mixolydian, emotionally charged and suitable for lament, was also frequent in tragedy, and Plutarch describes Euripides himself teaching a tragic chorus a Mixolydian ode (De audiendo 46b).

It is difficult to believe that Euripides did not make his Phrygian sing in the Phrygian mode, especially since that character’s dramatic ‘aria’ includes reference to the ‘Idaean Mother’ (Cybele), with whose rituals the Phrygian mode was often associated. Moreover, Euripides himself has left us a small clue as to the nature of the music that the Phrygian sung.

In a line needlessly excised by many editors as an intrusive stage-direction,[3] the Phrygian refers to his own song as a harmateion melos, a “chariot song”. This is plausibly identified by an ancient scholiast as alluding to the harmateios nomos, an obscure musical genre associated with the semi-mythical Phrygian aulete Olympus, and was probably high in register, in the Phrygian mode.[4] This accords perfectly with the dramatic context in the Orestes, and suggests that the Phrygian sung in the Phrygian mode, at a high pitch – specifications we naturally followed when composing our music.

With a good idea of which modes to use, it was important to establish some principles on which to turn text into music. The surviving musical fragments, and especially the Orestes papyrus, gave us some clues. As has long been noticed, the attested fragments make much more frequent use of melodic motion to the adjacent note in the scale than large jumps, although when jumps are used they tend to follow particular key intervals that often recur in a piece.[5]

The Orestes fragment conforms to this trend, though it also evinces another important stylistic feature: repetition of melodic patterns, often around different tonic foci. One device that we know contemporaries considered to be characteristic of Euripides’ music is what we now call ‘melisma’ (a term inherited from the ancient theorists, where it has a similar but slightly more specific sense). This is the setting of a single syllable to several notes.

In Aristophanes’ Frogs there is a brilliant parody of Euripides’ lyrics, which includes (1314) a form of the classically Euripidean word εἱλίσσω (=ἑλίσσω, helissō, “whirl”, written rather strangely: εἱειειειειειλίσσετε, hēiēiēiēiēiēilissete, “you whirl”.[6] Again, a few lines later (1348), we find εἱειειλίσσουσα (heieieilissousa). This is in fact a standard way of writing vowels, in the surviving musical documents, when the setting is melismatic; i.e., when the syllable is to be sung to two notes, it is often written twice, when to three, thrice, etc. (The Orestes papyrus itself shows this feature.) Thus we can be sure that Aristophanes, at least, who clearly knew Euripides’ plays very well, associated melisma with Euripidean music – so we have accordingly made use of it in our own setting.

We decided that all metrically responding strophes and antistrophes would also have, in our setting, the same melody.[7] It is not clear whether Euripides would have repeated exactly the same melody, but to do so presents practical advantages when training a chorus in much less time than was available to Euripides and his cast. While the majority of surviving Ancient Greek music follows in its melody the pitch accents of the text according to certain deducible principles,[8] the Orestes papyrus deviates from these principles, suggesting that the ‘New Music’ of the late 5th century – with which Euripides was certainly linked – may have followed accentual contours less rigorously, at least in strophic texts.

Moreover, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Comp. 11) describes what he apparently assumes to be Euripides’ own melodic setting of Orestes 140–2 (the first choral ode of the play), and it is clear that the tune he knew was quite happy to violate the normal rules of accent-melody correspondence. However, recent statistical and interpretative work by Anna Conser[9] has demonstrated that at least some choral odes by Aeschylus show enough correspondence of accentual patterns between strophe and antistrophe to allow, within the fairly loose limits of the standard rules of accent-melody matching, both strophe and antistrophe to be sung to the same melody whilst following the accentual contours of both.[10]

We did not carry out a statistical analysis of the accentual patterns of the Orestes, but we did notice in the process of composition that in a number of responding odes there was a closer match of accentual patterns than might have been expected by chance. Where this was particularly striking, we wrote a melody that followed the contours of both passages – the metrically responding sections of both the strophe and antistrophe. In other sections, we often took a freer approach, giving precedence to other factors, such as word-painting or the recurrence of melodic phrases as seen in the Orestes papyrus.

It should be said that the Orestes includes a significant number of lyrics that are not in responsion to another ‘stanza’: epodes that follow on a responding strophe and antistrophe, and most notably the Phrygian’s long solo. In these cases we followed a similar procedure, keeping the accentual patterns as a constant guide but not infrequently letting other considerations take precedence.

The process of composition is best illustrated by an example. The parodos, or opening song of the chorus, is in the Orestes rather unusual: a worried, hushed dialogue between the chorus and a miserable Electra, in which lament for the fate of Orestes is overlaid by the fear of waking him up. A scholiast (anonymous ancient commentator) writes that “the song is sung on the so-called nētai [top notes] and is very high… because the high register is typical of people lamenting. And the song is as light as can be [leptotaton].”

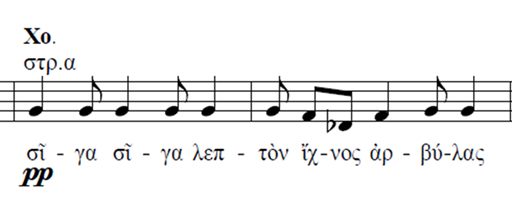

For the opening three lines, Dionysius of Halicarnassus describes the melody; strictly speaking, he specifies word by word where the melody he knew does not follow the accent – implying that where he is silent, the melody and accent were likely in accord. The opening two lines are sung by the chorus:

σῖγα σῖγα, λεπτὸν ἴχνος ἀρβύλας

τίθετε, μὴ κτυπεῖτ’

Silence, silence, place the tread of your boot softly, don’t stamp!

According to Dionysius, the first three words (σῖγα σῖγα, λεπτὸν: silence, silence, soft) were all sung on one note, and in ἀρβύλας (boot) the second and third syllables were sung on the same note. ἴχνος he passes over. And so on. It is clear from the sense and from the scholion that these words should be sung very softly, and high up; we began above the mesē (the tonally important middle note of the mode), in the Dorian mode. Following Dionysius’ specifications and choosing notes from the Dorian mode, we ended up with the first two bars as following:

The sustained high opening indicated by Dionysius and the scholion perfectly suits the hushed, breathless, stepping entry of the chorus. (It is, we may note, equally suited to the corresponding antistrophe, where we have used the same melody.)

Beyond such ancient testimonia, the words of the play itself can give clues to the musical setting. Just a little further on in the same opening ode, the chorus responds to Electra’s plea to move away from the bed with the exclamation, “Look, I obey!” In response, Electra cries Ah, ah! and begs them with increased urgency to speak as quietly as possible. It seems clear that the chorus, in its over-enthusiastic response, has broken the hushed tone and been too loud, risking waking up Orestes.

Likewise, in the corresponding section of the antistrophe, the chorus responds to the information that Orestes is breathing erratically with the exclamation: “What are you saying! Oh, the wretched man!” This again draws Electra’s ire, and she reminds them in reply that it will be the end of Orestes if they wake him up. The natural conclusion is that both corresponding exclamations from the chorus stood out musically, and were louder than the surrounding lines: we have set both on a repeated loud note near the top of the mode.

Early Greek music seems to have largely chosen one mode and stuck with it for the duration of a piece. There is good reason to believe that the New Musicians of Euripides’ day, however, made dramatic – and, to some, scandalous – use of modulations between different modes. Not wishing to deny ourselves what was likely a distinctive feature of Euripides’ music, we determined to make judicious use of modulation. Here the input of our aulete, Callum Amstrong, was very important, since the technical capacities of Classical-era auloi are such that not all modulations between different modes are possible or equally efficient. The modulation that works best – due to systematic congruences in the modes – combines Dorian and Mixolydian, and we made the most use of this throughout the play. (The method of modulation, implied in ancient texts and musically effective, is to switch from one mode to the other at the point in which they happen to share a common note.)

Rather than change modes at random, though, it made sense to use modulation for musical and especially for dramatic effect: remember that, according to the ancients, different modes have different ‘characters’ and associations. Thus we changed from Dorian to Mixolydian, for instance, when the tone changed and emotion was heightened. We devised a more programmatic use of mode for the Phrygian’s ‘aria’: he naturally sings in the Phrygian mode, but sometimes he ‘quotes’ the words of Orestes or Pylades, and when he does so we had him switch to the Mixolydian. This allows musical differentiation to follow the dramatic and semantic shift, without even requiring a pause or disturbance in rhythm.

Finally, a few words should be said on the thorny topic of rhythm. In one sense, all Greek poetry already comes with a rhythm, since it is built out of patterns of ‘long’ (heavy) and ‘short’ (light) syllables. There is much debate as to how far Greek musical rhythm simply followed mechanically the patterns of longs and shorts of the metre. Certainly composers could take licences in the process of rhythmopoeia (“rhythm-making”), the most common of which was to prolong a double-length long syllable (diseme, like our crotchet) to a triple-length triseme (like our dotted crotchet). ‘Trisemes’ are sometimes indicated in the extant musical documents, but rhythmical notation is simple and sparse, suggesting that musical rhythm did largely tend to follow metrical patterns.

We have been quite conservative on this issue, and followed the metre rather exactly. It is worth noting that in some metres the basic pattern requires a short in a certain position, but a long syllable can be substituted in instead. In such cases we have often chosen to opt for what nowadays would be called a ‘dotted’ rhythm, using a note in between the length of the other shorts and longs, on the strength of the ancient rhythmicians’ talk of a proportionally “irrational” rhythmical foot: this allows adjacent bars in a series in one metre to stay the same length. The interpretation of the ‘irrational foot’, however, is hotly contested in the scholarship, and the ‘dotted rhythm’ sometimes feels musically very effective, sometimes less so. Occasionally, therefore, we have kept all long syllables the same length, and lengthened the bar as a whole.

Specialists may judge whether we have made the best use of the ancient evidence, taken the most defensible stance on controversies, and interpreted fragments and testimonia correctly; but it is for the audience to judge whether the result is musically effective. Whatever Euripides would have thought of our music, it is born from the depths of his own text.

A striking experience during the rehearsal process gave me subjective confirmation that we were at least headed in the right direction. Our aulete, Callum, remembered that several years ago he himself had also written music for a number of the choral odes of the Orestes – a fact of which Beth and I had been completely ignorant of as we composed our score. And yet. astonishingly, the two versions, though written entirely independently, have sequences of bars, and indeed a whole line or two, that are completely identical. Pure chance? Or is it rather that the seeds of the music are latent in Euripides’ own text, in the ancient modes and in the preserved auloi themselves, just waiting to be brought to light again…?

Nicholas Romanos is the current president of the Oxford Ancient Languages Society, and the director, (co-)composer, and coryphaeus of its production of Euripides’ Orestes. He is a student of Classics and Sanskrit at the University of Oxford, and has recently written on Racine and Virgil (Arion), and August Wilhelm Schlegel’s edition of the Bhagavadgītā (Warwick Journal of Philosophy, forthcoming). He is also a member of Oxford Latinitas.

Further Reading:

The first port of call for an introduction to ancient Greek music is still, despite much intervening progress in scholarship, M.L. West’s magisterial Ancient Greek Music (Oxford University Press, 1992).

The musical fragments themselves, including the Orestes musical papyrus, are collected in E. Pöhlmann & M. L. West, Documents of Ancient Greek Music (Oxford UP, 2001).

Translations of the theoretical texts are easily accessible in A. Barker’s indispensable Greek Musical Writings: II. Harmonic and Acoustic Theory (Cambridge UP, 1989). For rhythmics, see the useful collection of fragments in L. Pearson. Aristoxenus: Elementa Rhythmica (Oxford UP, 1990). Pearson’s commentary, however, is unreliable.

The literature on the musical fragment of the Orestes is extensive. For a speculative but methodical reconstruction of its melody (which we incorporated into our score), see A. D’Angour, “Recreating the music of Euripides’ Orestes,” Greek and Roman Musical Studies 9 (2021) 175–90. On Euripidean music in general, especially in relation to the ‘New Music’, the classic paper of Eric Csapo is a good starting point: “Later Euripidean music,” Illinois Classical Studies 24/25 (1999–2000) 399–426. On the music of tragedy and accentual patterns, see the recent, important work of Anna Conser: “Pitch accent and melody in Aeschylean song,” Greek and Roman Musical Studies 8 (2020) 254–78; and “Aiola nux: the musical design of Sophocles’ Trachiniae,” Arethusa 57.1 (2024) 105–47.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Rather confusingly, these have nothing to do with the modern scales of the same names! |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | This is ultimately uncertain and unknowable. But there is no particular reason to think it is not, and we do have cause to associate the papyrus melody at least with the general stylistic grouping to which Euripides belonged. |

| ⇧3 | Note that even if this were the case, the implications for Euripides’ musical setting of these words would be the same. |

| ⇧4 | Cf. M.L. West, Ancient Greek Music (Oxford UP, 1992) 339. |

| ⇧5 | Ibid., 190 ff. |

| ⇧6 | The line number 1314 is according to Nigel Wilson’s OCT; different manuscripts offer different numbers of ‘ει’s! |

| ⇧7 | Cf. Dion. Hall. Comp. 19, especially the phrase τοῖς δὲ τὰ μέλη γράφουσιν τὸ μὲν τῶν στροφῶν τε καὶ ἀντιστρόφων οὐχ οἷόν τε ἀλλάξαι μέλος, which (perhaps) means “But those who write lyric poetry cannot change the melody of strophes and antistrophes.” Whether this implies precise melodic repetition, however, is not entirely clear. |

| ⇧8 | On which see M.L. West (as n.XXX) 199. |

| ⇧9 | Conser went on to compose a score, based on her research, for the 2019 Colombia production of Herakles, which our aulete Callum Armstrong accompanied. |

| ⇧10 | Anna Conser, “Pitch accent and melody in Aeschylean Song’, Greek and Roman Musical Studies 8 (2020), 254–78. |