Nicholas Romanos

Ἔστι τινα ποιήματα ἃ οὐ μόνον ἐμμέτρως γέγραπται ἀλλὰ καὶ μετὰ μέλους ἔσκεπται… ταύτην οὖν τὴν λυρικὴν ποίησιν δεῖ μετὰ μέλους ἀναγιγνώσκειν, εἰ καὶ μὴ παρελάβομεν μηδὲ ἀπομεμνήμεθα τὰ ἐκείνων μέλη.

There are some poems that are not only written in metre, but are composed with a melody… such lyric poetry, then, ought to be performed with music, even if the original melody has not been passed down to us by tradition and does not remain in our memory. (Diomedes/Melampus, scholion to Dionysius Thrax, GG 1.3, p.21 Hildgard)

Late afternoon, at the end of November, in an Oxford College. The audience shuffles into a theatre, as chorus-members don their peploi behind the scenes. The eager ear can catch the clear-singing tones of a classical aulos warming up around the corner. Soon, two hours’ worth of Ancient Greek dramatic poetry will be performed, by a cast of 25 students and scholars from Oxford and around Europe.

All lyric passages will be sung, accompanied by renowned aulete (i.e. ancient pipe-player) Callum Armstrong, to music composed for the occasion, following all that we know of Euripidean musical style, and incorporating an ancient melodic fragment. Five audiences will watch this performance, over four days, filling Keble College’s O’Reilly theatre for every performance. This is the Oxford Ancient Languages Society’s production of Euripides’ Orestes.

An ancient performance of Greek tragedy was a multifaceted experience. Besides the physical setting and social context, music, masks, costume, dance, gesture, and staging all contributed to the characteristic artistic impression in ways that clearly went beyond the bare text as printed in our editions. And as much as we may wish otherwise, it is not possible simply to ‘recreate authentically’ a 5th– (or 4th-…) century performance of an Athenian tragedy: there are too many gaps in our knowledge of crucial details. (In any case, nowadays the very concept of ‘authenticity’is held, not without some reason, in suspicion.)

Nevertheless, it is the business of scholarship to collect methodically all the evidence that may further our understanding of Greek tragedy, to organise and to interpret it. In this sense, a good scholarly commentary on a play, which necessarily crosses disciplines, discussing as completely as possible all matters of text and interpretation, includes in potential a dramatic production.

The aim of the Oxford Ancient Languages Society production was to follow this scholarly method – as rigorously and completely as practically possible – through to the harvesting of its dramatic fruits, and to demonstrate that meticulous textual scholarship can indeed lead, quite naturally, into stunning drama.

This should not, of course, surprise us: the Attic tragedians were outstanding dramatists, and a production such as this takes us about as close as we can hope to get to the dramas as they were performed on the Attic stage. Not because it is a perfect recreation, but because it actualises the dramatic potential of the text itself, with reference to wider ancient evidence; by no other method could we hope to get closer.

Euripides’ Orestes is the perfect play for this sort of project, since it is arguably the most dramatically innovative and clever play by the most innovative and clever of the great tragedians. It is hardly surprising that it was in antiquity one of the most popular of all tragedies. With this drama Euripides stretches the boundaries of the tragic form, bending conventions and staging ever bolder and more exciting turns of events. The entry of the chorus, for instance, is unique and strikingly effective, adapting the choral ode that is usually sung on entry to a situation where an anxious chorus must not wake Orestes, who is currently asleep…

We had not the slightest doubt that the play should be performed in the original Greek. But the major editions currently in use show enough variation regarding such dramatically crucial matters as interpolation and the order of lines, alongside many smaller issues, that it seemed necessary to start afresh and make our own (modest) edition of the text.

Secondly, our ambition was to stage a Greek play in which all the actors and singers understood Greek. This was possible thanks to the wonderful community that surrounds the Oxford Ancient Languages Society (OALS), whose regular members make up much of the cast, and many of whom are able not only to read Classical Greek but also to speak it! The OALS has as its mission to promote engagement with and study of ancient languages and their texts, among people of all backgrounds, through the active method, speaking and listening to the languages as well as reading and writing them.

What better way to achieve this, internalising the language and immersing oneself in the text, than to commit to memory and perform hundreds of lines of a Greek drama – or to sit in the audience and hear the Greek being sung through the lips of masks, while watching the drama unfold on stage?

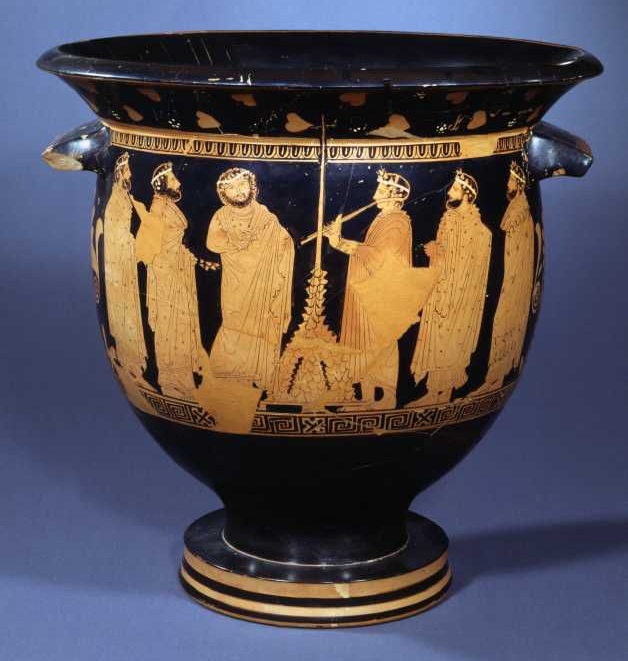

Costumes and masks are wont to push the bounds of both budget and practicability, and yet they can be central to an audience’s experience of a drama. Masks are particularly significant in that they fundamentally effect the style of acting, the visual experience, and the audience’s relationship to the actor. As such, our dedicated team pored over texts and vase paintings to design and create garments that would not have looked out of place to an Athenian audience. In particular, special care was taken to pay attention to all the passages of the text itself that hold particular implications for costuming.

At the heart of our Orestes was the music. Classical scholars have long recognised that rich insight may be gained from the study of the Athenian tragedies as texts written for and experienced in performance. Likewise, the study of Ancient Greek music has in the last few decades made strides previously unimaginable, thanks to the discovery of a not insignificant corpus of ancient musical fragments, and some monumental feats of scholarship.

Nevertheless, given the almost complete absence of any surviving melodies from the 5th century, when all the surviving tragedies were written, most students of Greek tragedy are still largely resigned to reading and interpretating the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides with no reference to music, and often with little regret at the apparent necessity of such an approach. For Euripides this is not quite as forgivable as for Aeschylus and Sophocles. The young Hellenist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff once wrote that “No tragedian (as in the case of Phrynis or Timotheus) is a musical specialist.” In the light of recent work on Euripides’ relationship to the ‘New Music’ of the late 5th century, however, such a view is no longer tenable.[1]

Our production took as its motto the words of an obscure commentator on the grammar of Dionysius Thrax, given above as the epigraph to this article: we should sing this poetry, even when the original melody is not preserved. And after all, we do in facthave the original musical modes or something quite close to them.

For the Orestes we are uniquely fortunate to have some indications about the original music of the play; but, above all, we have the text of the lyric verses of the chorus, Electra, and the Phrygian – a text that we know was written to and for music. Indeed, it is clear from the plain text itself that the music of the Orestes was innovative, bold, and dramatically crucial.

In particular, the Phrygian’s ‘aria’ is clearly a musically sophisticated and highly dramatic concert piece, of a kind clearly recognisable from Aristophanes’ parody of Euripidean lyrics in Frogs. It also bears a close relation to Timotheus’ Persians,although it is difficult to say which work was written first.

Where no melodic fragments at all remain one cannot, of course, claim to ‘reconstruct’ Euripides’ original music; but one can bring out the musical potentialities of the text itself in a way concordant with everything we do know about Euripidean music. This is what we aimed to do in this production, and it has not only the scholarly value of deepening our understanding of the text itself, but also a transformative effect in performance. It is not for nothing that the Greeks were obsessed with the ēthos of their music.

It is only in the last decade, or less, that a production like this has become possible: a crucial part of the Greek tragic soundscape was the aulos or double-pipes, and it is only very recently that these instruments have been reliably reconstructed from surviving remains, and have found skilled musicians willing to play them. There are still only a handful of professional auletes in the world, though they reach extraordinary levels of virtuosity. It was thus a pleasure and a privilege to work with Callum Armstrong, who stands in the front rank of aulos practitioners.

Our production of the Orestes was very much a team effort. More than fifty people worked on it in various capacities – students, scholars, and others; few of my friends and acquaintances in Oxford have not made some contribution. Though it seemed at times like madness to compress into the compass of a few weeks the preparation that would have taken an Athenian chorus the best part of a year, the result was a transformative experience for many of us in the cast – and, so we have been told, for many of those in the audience.

We are most grateful to all those whose generous support made the play possible: Elliniki Agogi, Sir Martin and Lady Smith, Sir David Lewis, Allison Ellis, Dr Gopal Chopra, Nicholas Barber CBE, Dana Frank, Peter Aherne, and the JCR of Jesus and Wadham College, Oxford

Given the rather rapturous accounts from some of those in attendance, we couldn’t help thinking that our play came off rather well. But we would like to let you be the judge: we recorded the play, and are preparing a film of the full production, alongside a short introductory video. Unfortunately, we are still seeking £2,000 to cover the costs of digital production and make this possible.

To this end, we have launched a crowdfunding appeal, and we are very grateful to Antigone for allowing us to broadcast that here. Any contribution that anyone feels able to make, however small, would be hugely appreciated. We are keen to recognise any support in the credits of the film (up to the point when the film has been finished and released!) and any future promotional materials: please feel free to contact us (oxfordancientlanguages@gmail.com) if you would prefer for your support to remain anonymous.

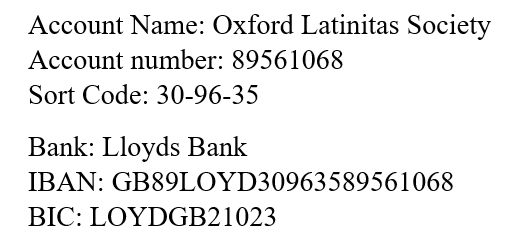

In addition, we can accept donations via this Paypal link or via the Oxford Latinitas Society on these details:

We are extremely grateful for any donations you may consider!

Meanwhile, two further pieces, on the interpretation of the Orestes, and on our approach to setting Euripides to music for our production, will appear on Antigone in the next couple of days.

Nicholas Romanos is the current president of the Oxford Ancient Languages Society, and the director, (co-)composer, and coryphaeus of its production of Euripides’ Orestes. He is a student of Classics and Sanskrit at the University of Oxford, and has recently written on Racine and Virgil (Arion), and August Wilhelm Schlegel’s edition of the Bhagavadgītā (Warwick Journal of Philosophy, forthcoming). He is also a member of Oxford Latinitas.

Notes

| ⇧1 | See e.g. E. Csapo, “Later Euripidean Music,” Illinois Classical Studies 24–5 (1999–2000) 399–426. |

|---|