Connor Beattie

With the release of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II, Roman gladiatorial combat has once again been thrown into the popular limelight. Like its predecessor, the film is set in the Principate when emperors ruled Rome; specifically in the reigns of the twin emperors Geta and Caracalla (211 AD). By this time, gladiatorial games had long been a form of public entertainment in Rome with huge amounts of money spent on putting on lavish displays for the crowds. But what came before the Colosseum, the gladiator schools (ludi), large groups of gladiators fighting against one another or against exotic beasts? Where did the phenomenon of gladiatorial combat begin?

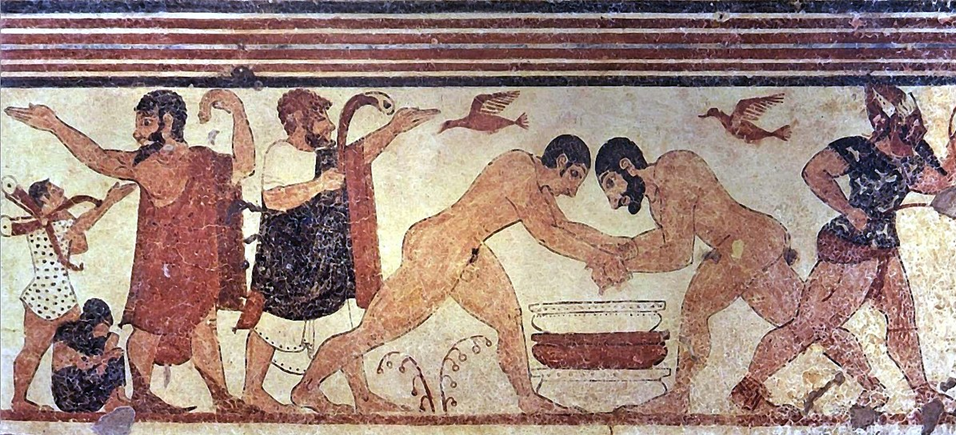

Writers, ancient and modern, have put forward various theories for the origins of Rome’s gladiatorial combats. Some think that they inherited the practice from Campania where Etruscan and Greek practices of duels at funerals merged with the ‘Phersu Game’ – a ritual, depicted in ancient tomb paintings, involving a dog ripping apart a blindfolded man until he died.[1] Other options for its origins are Etruria, Samnis and even Gaul. It is hard to decide exactly where the phenomenon of gladiatorial combat originated and, in any case, is not necessary for understanding it as it manifested in a Roman context.

For its origins in Rome we have to go back to the 3rd century BC and the funeral of Decimus Junius Brutus (consul 292) in 264 (Livy, Per. 16, Valerius Maximus 2.4.7). Initially, gladiators fought in paired single-combat bouts at the funerals of distinguished Roman aristocrats, with the number of pairs increasing over the 3rd century. At the funeral of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (consul 232) in 216, his three sons put on gladiatorial combats between 22 pairs of gladiators (Livy 23.30.15). At the funeral of Marcus Valerius Laevinus (consul 220) in 200, his sons put on combats between 25 pairs of gladiators (Livy 31.50.4). At the funeral of Titus Quinctius Flamininus (consul 198) there were 74 pairs of gladiatorial combats, while at the funeral of Publius Licinius Crassus (consul 205) there were 120 pairs (Livy 41.28.11, 39.46.2). Therefore, gladiatorial bouts were single combats which took place at aristocratic funerals alongside banquets and other entertainments.

Historians have advanced a variety of theories on the purpose of these gladiatorial combats. For some, they were funeral rituals: “a munus mortis, an offering or duty paid to the manes, or shades, of dead Roman chieftains.”[2] The defeated gladiator was a sacrifice to the gods. Other historians prefer a more socio-cultural explanation. Single-combat was an important aspect of Roman martial identity in the early and middle Republic – the primary manifestation of virtus (manly courage).[3]

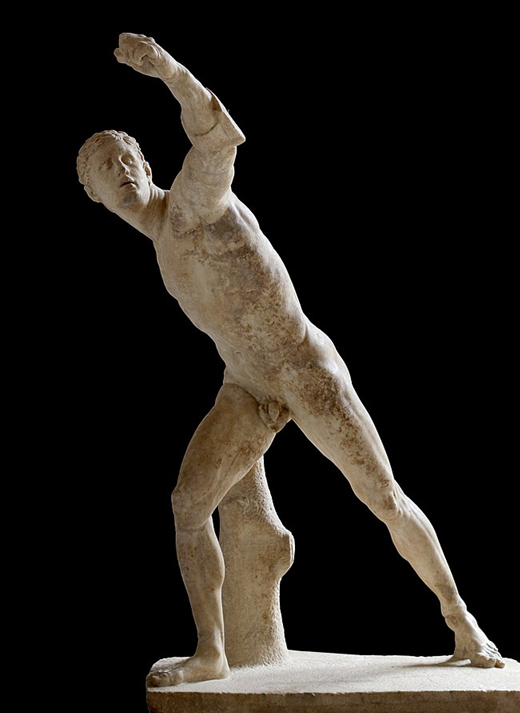

Roman citizen-soldiers received military decorations for feats of courage. For example, the corona civica (civic crown) was given to a soldier who saved the life of another Roman citizen; the spolia opima (rich spoils)was given to a Roman commander who fought and defeated the enemy commander in single-combat. Marcus Claudius Marcellus was the last Roman general to win the spolia opima,when in 222 he defeated a Gallic chieftain called Viridomarus at the Battle of Clastidium in single-combat. It is notable that, unlike in later periods, gladiators in the 3rd and 2nd centuries specifically fought in pairs – that is, single combats. In this way they encapsulated and presented the Roman ideal of virtus. It became a popular form of entertainment at aristocratic funerals because it played out single combats for an audience.

At the same time, it has to be acknowledged that early Roman gladiators were, normally, prisoners of war. They were defeated enemies who had been captured by the Romans in conflict and were now made to fight in Rome. Indeed, before the creation of a set of different types of gladiator named after the equipment and fighting styles they used (e.g. murmillo, retiarius, secutor) early Roman gladiators had ethnic labels. Our sources report at least two early ethnic-labels for gladiators: the Samnis (Samnite) and the Gallus (Gaul). The Romans had fought the Samnites in three major wars in the late-4th and early-3rd centuries, meaning that there would have been a large number of captured Samnite slaves in Rome in the period that gladiatorial combats were developed. Similarly, the Romans fought the Gauls on a perennial basis over the 4th and 3rd centuries.

As an exception that proves the rule, when Publius Cornelius Scipio – who would later take the cognomen Africanus after defeating Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC – held gladiatorial combats at New Carthage in 206 to honour the memory of his dead father and uncle, he did not need to use prisoners of war. Rather, warriors from Spanish tribes volunteered to fight to display their own courage and the prestige of their tribes (Livy 28.21.1-5).

Therefore, gladiatorial combats presented single-combats between Roman enemies making them a manifestation of imperial power. It allowed Romans to witness the killing of Rome’s enemies in an artificial battle taking place in Rome.[4] Perhaps this was the key point of early gladiatorial combats. Livy reported accusations made by the famous Cato the Censor against Lucius Quinctius Flamininus when he expelled him from the senate.

One element was that Flamininus used to take a male prostitute away from Rome before gladiatorial games were held. The prostitute, a Carthaginian named Philip, complained about not witnessing the gladiatorial combats and Flamininus replied: “seeing that you have missed the spectacle of gladiators, would you like to see this Gaul die?”[5] The consul was referring to a Gallic turncoat who was seeking protection from him. When the prostitute jokingly assented, the consul killed the Gaul in front of him (Livy 39.42.8-12). The story might have been fabricated gossip aimed to discredit Flamininus but the underlying assumption is that Romans would watch gladiatorial combats in order to see defeated enemies be killed.

So did the Romans admire the virtus displayed by gladiators or view them as defeated enemies? Perhaps it was the combination of these two different facets that really mattered. Michael Carter, a leading expert on Roman gladiators, suggests that the Roman aristocratic funeral itself is the key context through which to understand gladiatorial combat.[6]

Polybius, a Greek historian who came to Rome as a captive and subsequently became tutor to a leading Roman aristocrat Scipio Aemilianus, wrote extensively about aristocratic funerals. He described how a deceased aristocrat would be carried to the Rostra (speaking-platform) in the Forum accompanied by family members wearing the death-masks (imagines) of previous members of the family. Laudatory speeches (laudationes) were given and other ceremonies were held – it is likely that banquets and gladiatorial combats formed part of the entertainment.

Polybius wrote that funerals were a spectacle that inspired young men to risk everything for the res publica in order to demonstrate their courage and win glory (6.54.1-5). Perhaps gladiatorial combats were ultimately one means of elucidating this goal: seeing these single combats between Rome’s enemies, as well as the inevitable wounds and deaths, would have desensitised the Roman youth to acts of violence and, more specifically, to the killing of traditional groups considered Roman enemies. It might also inspire in them a desire to defeat such enemies in single-combat.

Yet do we have any evidence that gladiatorial combat inspired such behaviour in the Roman youth? There is perhaps one indirect indication. When Antiochus IV, who had spent time in Rome as a captive, returned to Syria and became king of the Seleucid empire he decided to hold gladiatorial games routinely. He had obviously witnessed many such combats in Rome and decided that they would be beneficial for his subjects to see. At first the spectators were frightened by these single combats because of the wounds inflicted and death of many of the gladiators. But, after conditioning his people to enjoy the games, “he aroused in most young men a zeal for arms” (Livy 41.20.11-13).[7]

This account suggests that Livy understood the function of gladiatorial combats to be inspiring such zeal for arms amongst Roman young men. Antiochus might have thought the same too. He admired Roman military prowess and introduced Roman-armed soldiers into his army at a procession at Daphne in 166. Perhaps he recognised that gladiatorial combat was an important aspect of Roman military culture and appropriated it to inspire the same culture in his soldiers in the Seleucid empire?

In summary, long before gladiators were performing before emperors and great crowds in the Colosseum, Roman prisoners of war were made to fight in single combats at the funerals of distinguished aristocrats. The earliest of these funeral bouts in 264 involved only a few gladiators and was intended to inspire young, elite Romans to defeat their enemies on the battlefield. These combats quickly grew in popularity and the number of gladiators increased into the hundreds.

Over time these gladiatorial combats became popular amongst the wider population and began to be held at festivals and games. In response, gladiatorial schools (ludi) were founded to train gladiators, which meant that gladiators themselves became professionalised. The entertainment then spread around the Roman empire and became particularly popular within the Roman army. Eventually, even emperors came to try their hand: Commodus did indeed fight gladiators but he was never killed by one, as in the film Gladiator. Instead he was strangled to death by a wrestler named Narcissus while taking a bath. Which is perhaps a less flashy way to die.

Connor Beattie is currently the Haworth Research Fellow at the Pharos Foundation and studied at Oxford for his BA, MPhil and DPhil. He specialises in Roman politics, imperialism and warfare in the Middle Republic.

Further Reading:

M. Carter, “Gladiatorial combat: the rules of engagement,” Classical Journal 102:2 (2006/7) 97–114.

V. Hope, “Fighting for identity: the funerary commemoration of Italian gladiators,” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 73 (2000) 93–113.

J.E. Lendon, “Gladiators” (review article), Classical Journal 95.4 (2000) 399–406.

Notes

| ⇧1 | J. Mouratidis, “On the origin of Gladiatorial games,” Nikephoros 9 (1996) 111–34. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | C. Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster (Princeton, NJ, 1993) 13. |

| ⇧3 | T. Wiedemann, “Single combat and being Roman,” Ancient Society 27 (1996) 91–103. |

| ⇧4 | D. Kyle, Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome (Routledge, London, 1998) 47. |

| ⇧5 | “vis tu,“ inquit “quoniam gladiatorium spectaculum reliquisti, iam hunc Gallum morientem videre?” |

| ⇧6 | M. Carter, The Presentation of Gladiatorial Spectacles in the Greek East: Roman Culture and Greek Identity (PhD Thesis, McMaster Univ., Hamilton, ON, 1999). |

| ⇧7 | armorum studium plerisque iuvenum accendit. |